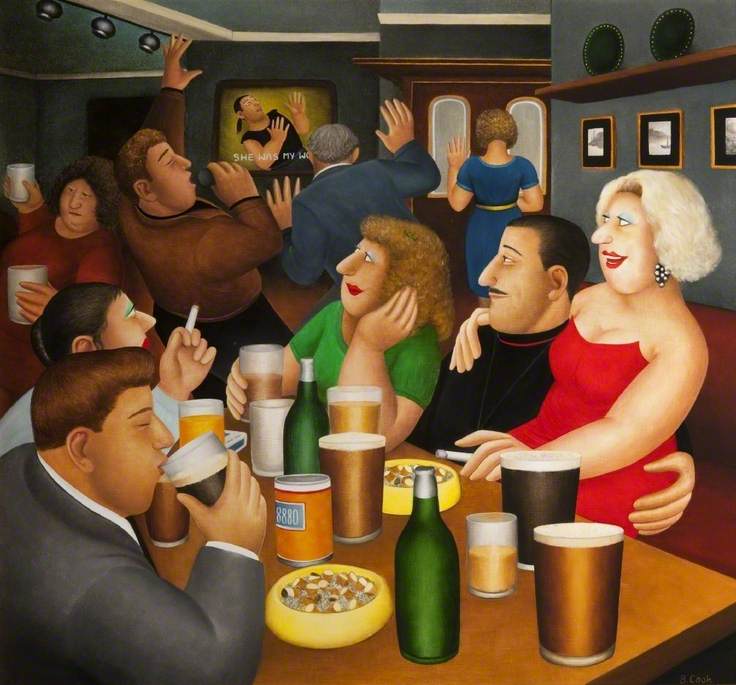

Sarah Lucas rose to prominence within the Young British Artists (YBA) of the 1990s and has since produced a unique and absorbing body of work.

Whilst interpretations of her practice, incorporating installation and sculpture, largely focus on the provocative and darkly humorous, Lucas' artworks can be read in more profound ways.

Frequently imbued with English cultural references and often offering a nod to art history, the artist's work explores themes such as gender and class, sexuality, mortality and the human condition itself.

Typically utilising materials from the everyday, or offering consideration of the ordinary object, has enabled comparisons of Lucas' work with that of the Dadaists and Surrealists. While such avant-garde movements aimed to mount a challenge to rationality, Lucas however considers the irrationality of the familiar while also exposing common truths with explicit honesty. Her sculptural work entitled The Old In Out (1998) is a perfect example.

Produced in the shape of a toilet bowl in (urine) yellow clear-cast resin, the work enables the viewer to contemplate the most intimate moments of everyday life. Not only tipping a hat to the readymades of Dadaists, particularly the impudence of Marcel Duchamp's claimed urinal Fountain (1917), the work also may be associated with a history of Anglo-Saxon scatological humour, from ancient folk tales to the comedies of contemporary popular culture.

As a recurrent motif in Lucas' work, the toilet can be viewed as a somewhat gendered statement. Unlike the masculine urinal, the toilet has associations with the private world of female experience, from menstruation to miscarriage. The title, in addition, exemplifies Lucas' frequent use of puns and double entendres, alluding to London slang, sexual acts, and of course, bodily functions.

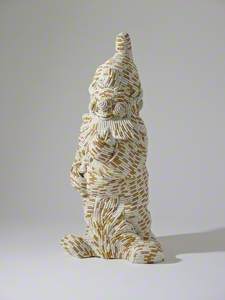

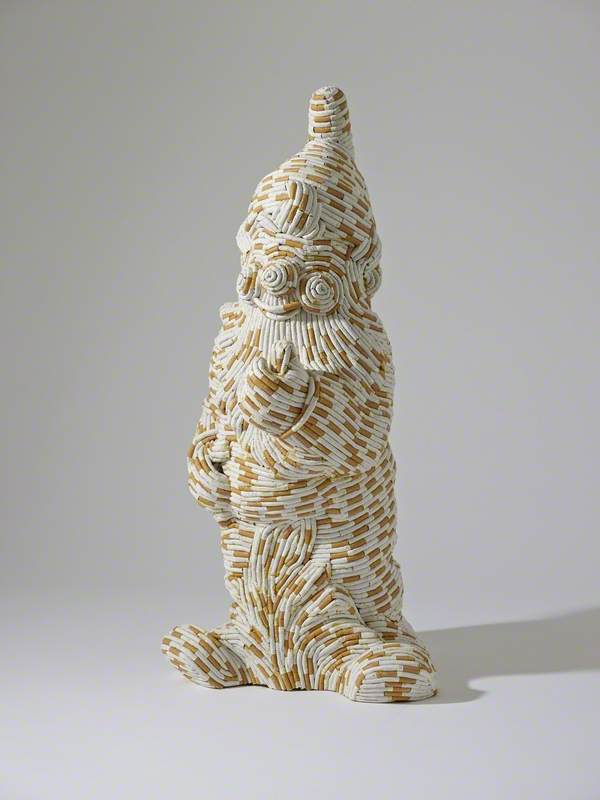

Witty wordplay and innuendo can be found in two other works, Willy (2000) and Percival (2007). The titles of both artworks reflect male names which are also informal British terms for a penis. The bizarre and comical combining of a plastic garden gnome coated in cigarettes can be compared to Surrealist explorations.

Méret Oppenheim's Object (1936), a fur-covered cup, saucer and spoon, for instance, may likewise confront expectations. The yonic connotations of Oppenheim's work can also be contrasted with the phallic implications of Lucas', and as the cigarette suggests lethal oral pleasures, the artist utilises absurdity to draw on the most basic of human themes: sex and death. Created while Lucas was giving up her own smoking addiction, in that sense, her materials relate a certain impotence.

German-born Swiss Surrealist Meret Oppenheim, Object, 1936 #womensart pic.twitter.com/8rWsul3T4Y

— #WOMENSART (@womensart1) November 30, 2017

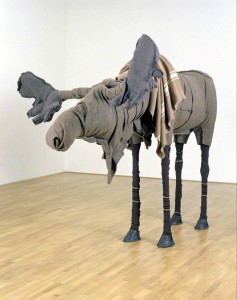

The nostalgic and kitsch associations with the garden gnome and also the china horse with cart, utilised as the subject for Lucas' life-size bronze work Percival, evoke ideas of aesthetics in relation to locale and also class. Transporting a popular mass-produced object of low artistic value from the domestic sphere into the highest cultural arenas, such as the gallery space, subverts notions of worth, taste and status in a practice stemming from Dada and Pop Art.

Lucas, however, typically anglicises her themes, emphasising a peculiarly British obsession with such knick-knacks which can be perceived as having particular class associations. In addition, the muscular horse may also be related to gendered ideals of masculinity, a common allusion in Western art.

Lucas appears to emphasise this with typical amusing representation, as the oversized marrows in the cart enhance both the fertility symbolism and comedic priapic ideas. Such bawdy references, apparent from Shakespeare's plays to the Restoration comedies of Aphra Behn, certainly continue here.

Sarah Lucas

— Synthetic Future(s) (@SynFutures) October 30, 2018

Cigarette Tits [Idealized Smokers Chest II]

(1999) pic.twitter.com/0tO87rRKkL

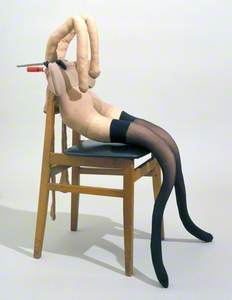

Lucas' artworks Cigarette Tits [Idealized Smokers Chest II] (1999) and Pauline Bunny (1997) further fulfil an amusingly lewd and sardonic remit, yet, as always there is more to be considered in the artist's work.

Created in the decade that coined the phrase 'ladette' – regarding laddish extremes of women's behaviour – and when internet pornography became mainstream, Lucas' suggestions of female figurative representation take on intriguing meaning.

The absence of human form in the first artwork, with emphasis only on the implication of specific body parts on an otherwise empty chair, may be considered as a critique of the vacuous male gaze.

While sexualised presentation is often idealised or illusionary, Lucas presents a darker reality as the materials of addiction subvert ideas of breasts representing sexuality or indeed, nurture and sustenance. The work could also be viewed as encompassing elements of self-parody and even social commentary on fellow females of Lucas' hard-living generation.

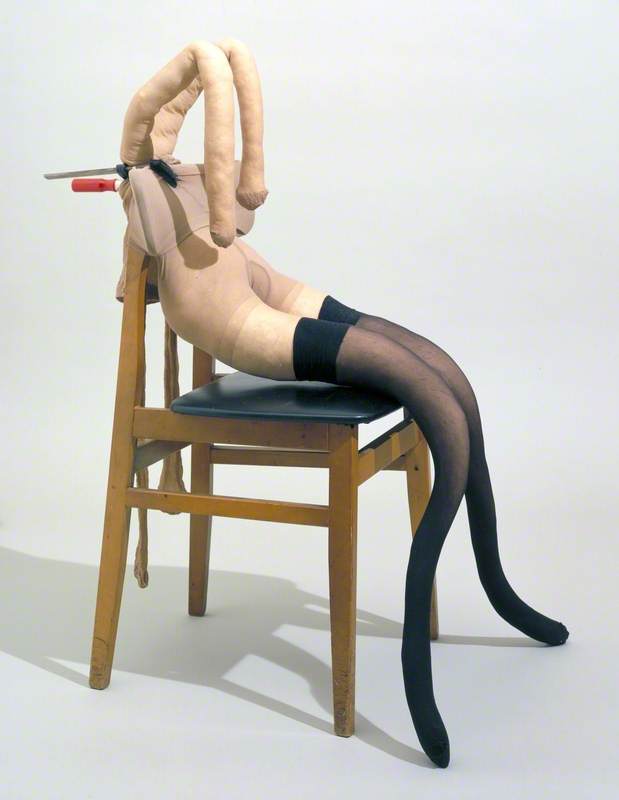

Pauline Bunny, a chair-bound soft sculptural work created with stuffed pantyhose, also encompasses deeper meaning. The work alludes to the infamous 'bunny girl' costumes and thus highlights ideas of objectification. Lucas accentuates the concept of the passive object through the limp arrangement and malleable materials, which contrast to the more rigid surfaces of the artwork.

The figurative form is headless and uncomfortably pinned down, while the emphasis is on the lower torso and stocking encased legs, in a satirised fetishist representation. The flaccid phallic drooping of the bunny-ear appendages only add to an air of ridiculed fantasy. Once again, Lucas invites the viewer to a sinisterly comic, yet seriously perceptive reading of her installations and sculptural forms.

More sex and also death are to be found in the artist's installation Beyond the Pleasure Principle (2000), with a title derived from the theories of Sigmund Freud. In a more complex arrangement than previous works, Lucas involves various elements, such as a partly suspended red futon mattress, bucket and electric light bulbs held between a cardboard coffin and commercial clothes rail. The scene not only evokes the dual obsessions of burgeoning psychoanalysis, but bondage, torture and disorder.

Within such expression, both masquerade and performance are hinted at by the clothes rail, yet this scenario is clothes-free, naked and exposed. The erotic pleasure encased in the soft fabric is also at odds with the metallic receptacle and harshness of the bare lightbulbs suggesting interrogation. As the metal material is employed as a vaginal opening, as part of an implied female form, a theme of instinctive human survival, through sex and reproduction, is paired in the work with contrasting impulses of human destruction.

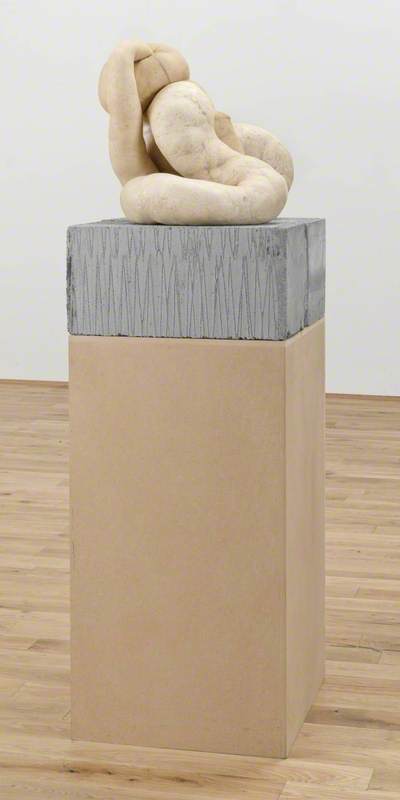

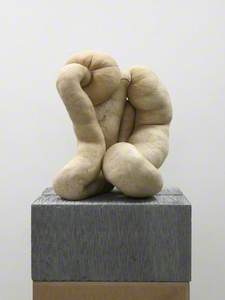

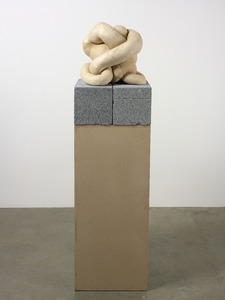

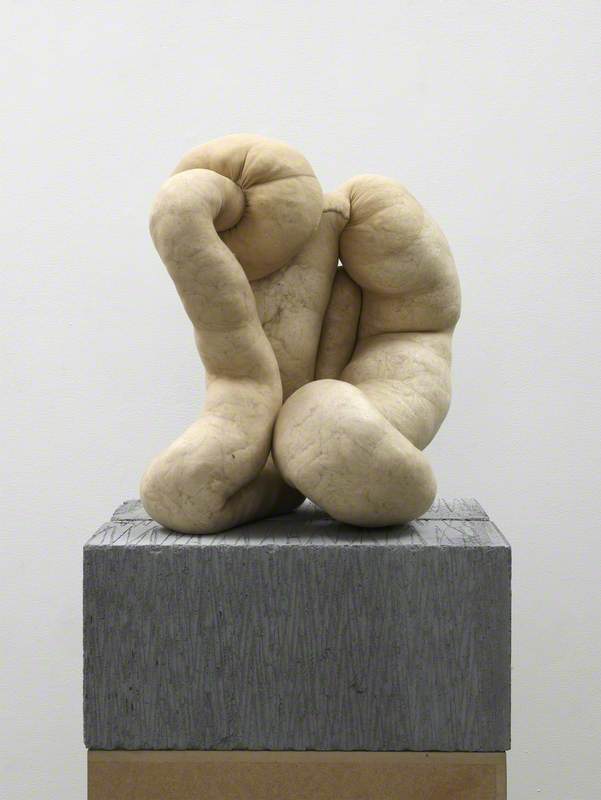

Finally, Lucas' NUD CYCLADIC series, which comprises individual sculptural forms created with the use of stuffed tan tights sitting on a conflicting hard plinth of common breeze blocks. While again utilising items from the everyday, the sagging forms produced by the artist are contrastingly ambiguous. Not quite representative of figures, the work somewhat resembles fleshy human body parts, such as entwined and contorted limbs or the remnants of a disembowelling.

Unlike previous gendered representations, Lucas' NUDs – a title evoking the incomplete nude – are not only sexless but appear barely human, almost alien.

While conjuring up suggestions of the biomorphic forms of English modernist sculptors Moore and Hepworth, the work may also bring to mind Louise Bourgeois' unnerving soft sculptural explorations.

As the French-American artist expelled her demons, Lucas' expression may also be viewed as a consideration of the internal, the psyche, and not the external at all.

As with most of the artist's work, Lucas utilises her art to peek behind the curtain of human existence, exposing the raw underbelly of life in captivating, disconcertingly insightful style. Long may she continue.

P. L. Henderson, art historian and founder of the #WOMENSART project

![Beyond the Pleasure Principle [Freud]](https://d3d00swyhr67nd.cloudfront.net/w800h800/collection/TATE/TATE/TATE_TATE_T07820-001.jpg)