What does it take to make a womb picture? To see beyond the visible with the technology of an MRI scan? To liken human anatomy to the very bones of the earth?

Since the 1970s, Sam Ainsley RSA has been asking such questions routinely through her art and teaching. Her work is political, an act of resistance, having frequently stood up as a spokeswoman for the arts.

She has been recognised by the Saltire Society as an 'Outstanding Woman of Scotland' and received an honorary doctorate from the University of Glasgow in 2018. Despite over half a century's career, the momentum and reach of Ainsley's art feels like a recent phenomenon that is only just getting started.

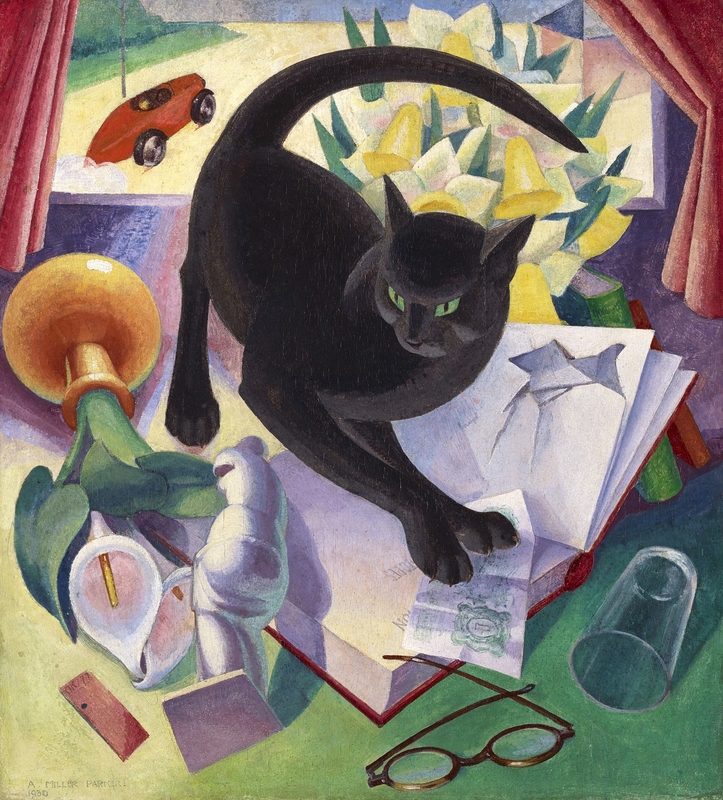

Ghost Cocoon

2009, acrylic on canvas by Sam Ainsley (b.1950)

Ainsley is arguably best known for the students who have passed through her 'sticky fingers', as she likes to describe her teaching of over 500 students at The Glasgow School of Art, firstly on the renowned Environmental Art course (1985–1991), then as leader of the MFA programme until her retirement in 2005.

In a recent exhibition of 'Scottish Women Artists', the curator Charlotte Rostek was right to acknowledge the 'Ainsley effect', namely Ainsley's education of generations of artists who became the foundation of Glasgow's reputation in the international art world.

Many of Ainsley's graduates (such as Christine Borland and Douglas Gordon) have won or been shortlisted for the highest profile art awards, from the Turner Prize to Becks Futures. 'All art is conceptual,' Ainsley insists, in response to being asked how her work connects to and differs from that of her famous students.

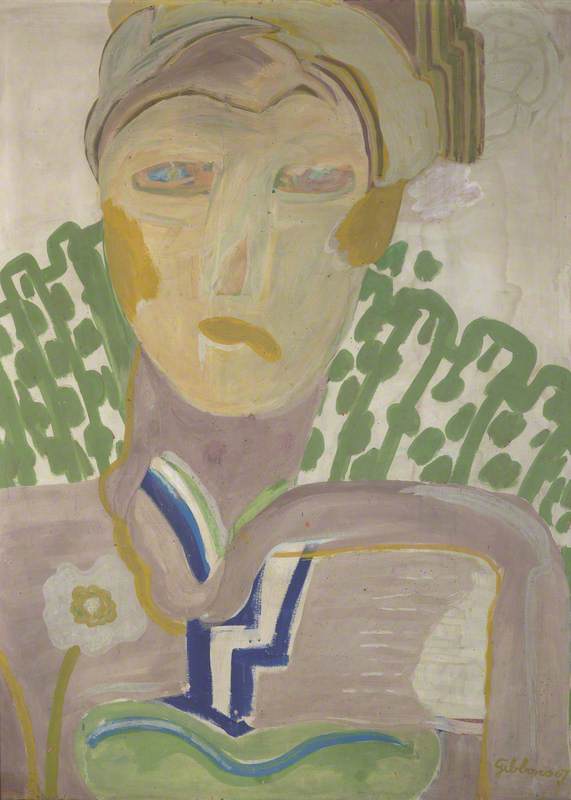

By the mid to late 1980s, Ainsley was already offering a sustained alternative to the machismo associated with the New Glasgow Boys (such as Steven Campbell and Adrian Wiszniewski). In response, Ainsley's figures became Warrior Women at 'Why I Choose Red', a major solo exhibition in 1987 at the Third Eye Centre in Glasgow – twice life-sized and in vibrant crimson rather than the 'dour brown' colour typical of her male contemporaries.

The art critic Clare Henry praised these figures as 'theatrical' at the time, and later reflected on the 'approachability' of such shaped canvases. Meanwhile, in the catalogue to the show, Stephanie Brown described Ainsley's warriors as emerging from 'chrysalises'. This attitude was followed up by a large banner that Ainsley made for National Galleries of Scotland to introduce the landmark Edinburgh Festival exhibition 'The Vigorous Imagination: New Scottish Art' in 1987.

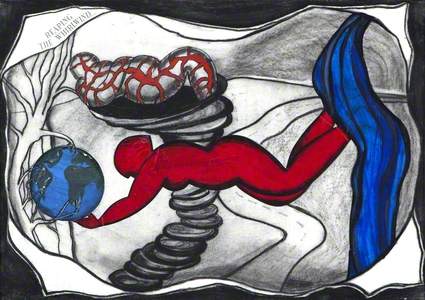

Such ideas continued with Ainsley's Gaia-like female figure clutching the blue marble in Reaping the Whirlwind. Yet, I would suggest that Ainsley's gift has been to revise such archetypes; hers are more thoughtful than the so-called 'mother-earth' cliché would have us believe. In 1979, the novelist Angela Carter insisted that myths 'obscure the real conditions of life', especially for working women. Ainsley likewise seeks to debunk and complicate our relationship with such mythical torchbearers to present a more down-to-earth viewpoint.

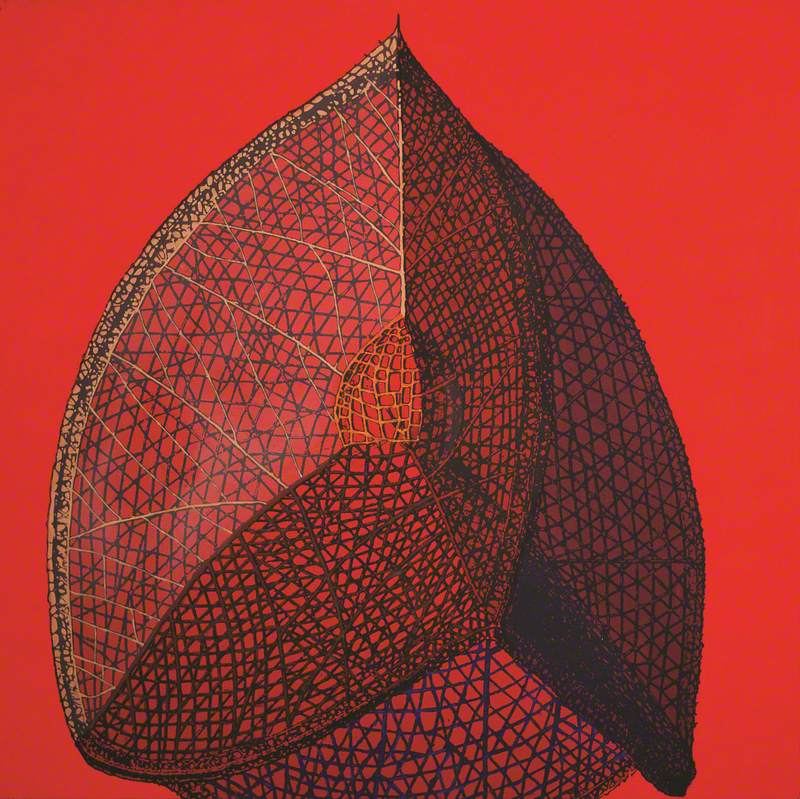

Like many women artists, Ainsley has a 'hybrid practice', meaning she works across a range of artistic media: painting, printmaking, wall drawings, collage and textiles. Such mixed media create a rich variety of textures and organic forms, and Ainsley often uses her signature cadmium red as a unifying pigment, connective tissue or 'red thread'.

Sewing, stitching, bias-binding and embroidery hoops are key techniques and equipment considered by Ainsley on a par with the fine arts. Interestingly, her chief inspiration comes from literature rather than art – from poetry and novels to cultural and critical history. Ainsley's Out of Redness Comes Kindness, her reception piece to the Royal Scottish Academy, is but one example, its title plucked from Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons (1914).

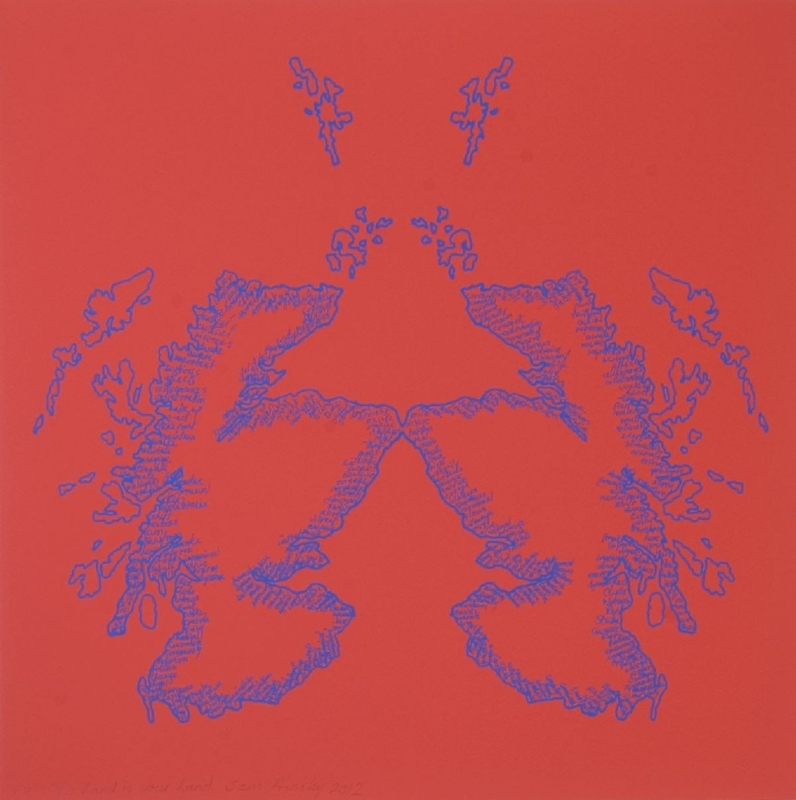

Out of Redness Comes Kindness

2008, acrylic on canvas by Sam Ainsley (b.1950)

As with the surrealist generation before her, Ainsley's work involves juxtaposition, meaning the merging of two otherwise separate realities on one aesthetic surface. Images copied or cut out from anatomy manuals and natural history collide or overlap in her artworks, conjuring strange, otherworldly landscapes.

Ainsley's artworks function on the edge between figuration and abstraction, concept and expression. In this respect, her work can be seen as a practical history of twentieth-century art, combining surrealism, expressionism and feminist slogan art. Surprisingly, Ainsley's maximal approach comes from minimal roots: the ability to select and isolate, to know when to pare back as well as when to layer up.

While some critics have been tempted to link Ainsley's work with the monumental cut-outs of Henri Matisse, Ainsley's figures are in fact closer to the jubilant nudes of outsider artist Niki de Saint Phalle in both form and attitude. Louise Bourgeois is another touchstone for Ainsley, not only her web-like yarns and maternal motifs, but also as an artist who has found fame (and the time to practise post-teaching and child-rearing) later in her career.

Ainsley wishes to be associated with the found objects and collage approach of Eileen Agar, and with the jagged dreamscapes of Kay Sage, two surrealist artists whose work hovers between reality and the imagination as a compass or set of coordinates.

Turning to Ainsley's own artworks, such 'emotional mapping' or countermapping appears in This Land is Your Land, a Rorschach-like mirroring of Scotland's distinctive shape. Here, the lung-like, butterfly-wing outline of the Scottish mainland is reinforced with Ainsley's handwriting around the edges, including motivational terms such as 'shift,' 'reverse,' 'believe' and 'turn'.

These words form a statement on her left-leaning views on the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, as well as a manifesto for creativity across the country. The dynamic terrains of Iceland and Japan as 'lands of ice and fire' have long intrigued Ainsley, as has 'the red centre' of Australia. Closer to home, Ainsley also considers her native region of Northumbria as an 'island' of sorts.

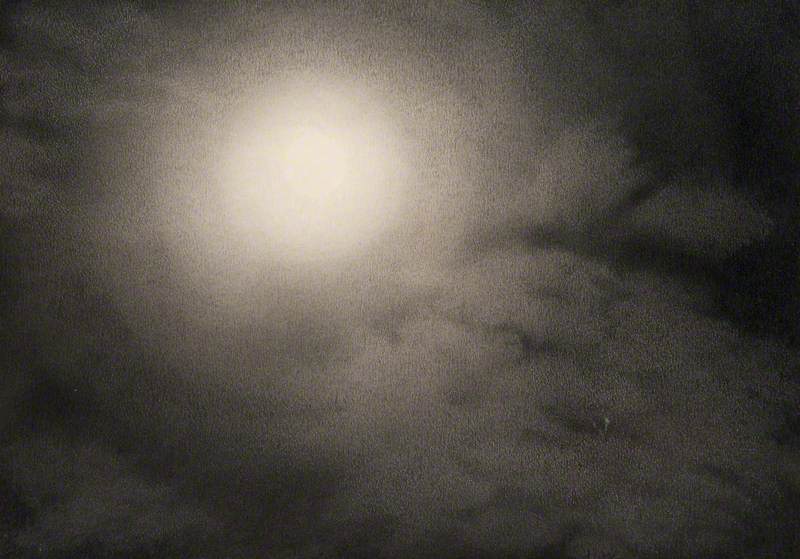

The Idea of North

2023, acrylic on canvas on red wall, Northumbria, Orkney, Iceland, Shetland, Fair Isle by Sam Ainsley (b.1950)

Elsewhere in Ainsley's portfolio, landmasses dissolve into negative spaces, with waterways forming the abstract landscape. This shores up Ainsley's view that water will one day be more precious than gold or diamonds. The zigzagging lines and contrasting colours are at once both the body's capillaries and a tree's roots. Such 'rhizomatic' thinking has been typical of art school teaching over the last 30 to 40 years, a French philosophical idea that creativity is non-linear and spreads out.

Womb with Tubular Forms

2023, acrylic on canvas by Sam Ainsley (b.1950)

Organs form a core motif of Ainsley's visual vocabulary. The bodily chambers of heart, womb and brain, and the scaffolds of skeleton, muscles and flesh are frequently realigned with the natural environment in Ainsley's art. Ainsley is a follower of Yi-Fu Tuan, a Chinese-American human geographer who draws connections between the body and the landscape. 'The earth is the human body writ large,' he tells us.

This gives Ainsley's work a rhythmic appeal: hearts beat and lungs inhale. This sense of vibration is further underscored by the 'simultaneous contrast' of her palette, where electric blue details appear to pulse against red backgrounds.

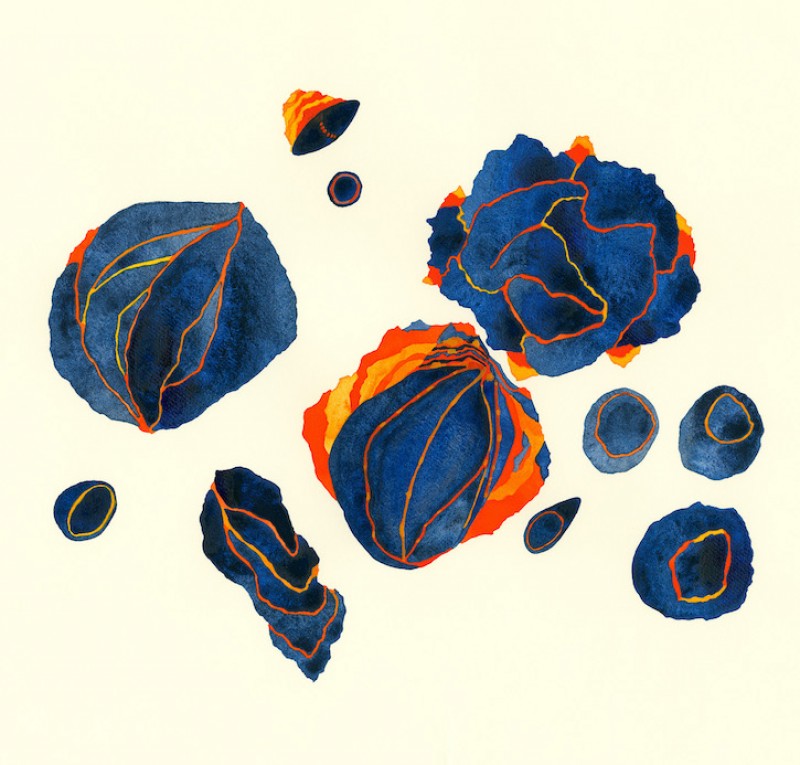

Untitled (Homage to D'Arcy Thompson)

2011

Sam Ainsley (b.1950)

A biological interest recurs in D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson's 1917 treatise On Growth and Form, which Ainsley cites among her chief sources of inspiration. Her Untitled (Homage to D'Arcy Thompson), features a conical seed pod, a microfossil of mathematically precise proportions.

For Ainsley, the miniature microcosm stands for the gigantic macrocosm. Her technique echoes this principle, moving from eight-by-eight-inch drawings in her small studio to large-scale printmaking in a collaborative setting. Cellular structures, grey matter and the tiny alveoli found within our very own breathing apparatus offer Ainsley a visual and physical framework of binding.

While her art seeks to liberate, she also offers a sense of safety blanket, security or cocooning – what the journalist Charlotte Higgins has recently described as the comfort of being 'held within a design or pattern'. Ainsley's art embraces the joys and agonies of being alive, all the better to see and know inside of ourselves.

Catriona McAra, art historian and curator

This content was supported by Creative Scotland