Every year, on 20th January, the Roman Catholic Church commemorates the life and death of the early Christian martyr Saint Sebastian (c.AD 256–288).

The patron saint of archers, pin-makers and athletes, as well as numerous cities around the world, the figure and holy death of Saint Sebastian has been revered for many centuries, and his story of religious defiance in the face of tyranny continues to resonate.

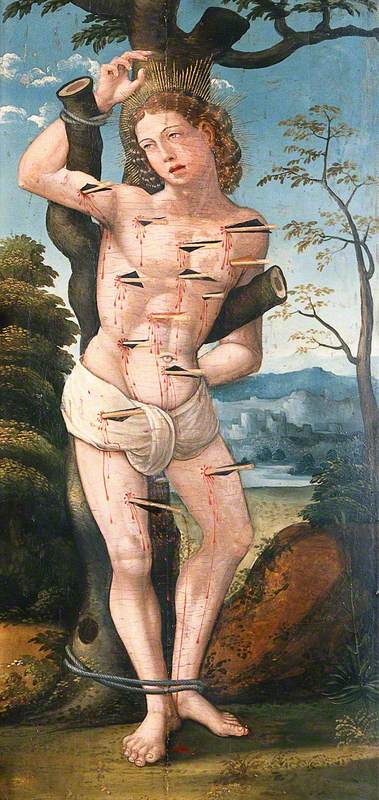

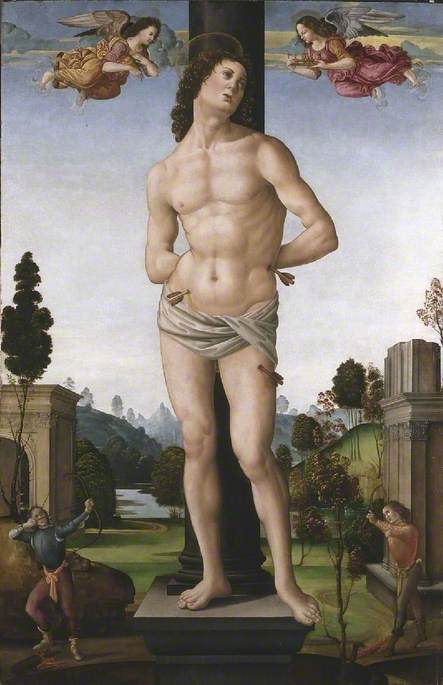

The image of Saint Sebastian tied to a post or tree – his body riddled with protruding arrows – has since become iconic in art history. Yet his image has transformed quite dramatically over the centuries.

According to a fifth-century hagiography, Saint Sebastian was a middle-aged Roman soldier who served under the pagan emperor Diocletian who ruled at the end of the third century AD.

As a Christian, Sebastian was sentenced to death by archer firing squad as part of the Diocletianic Persecution – the last and most severe attack on Christians in the Roman Empire.

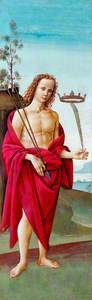

Saint Sebastian Bound for Martyrdom

1620–1621

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641)

Somewhat miraculously, Sebastian was not killed by this onslaught of arrows. He was nursed back to health by Saint Irene, as depicted in a painting by Nicolas Régnier (c.1590–1667).

After his recovery, Sebastian confronted Diocletian publicly and was clubbed to death for his impudence. His dead body was dumped in a sewer before it was retrieved by Saint Lucy and buried in a Roman catacomb, where a basilica bearing his name still stands.

The legacy of Saint Sebastian has continued through art history, particularly through sculpture and paintings that depict his moment of torture and eventual demise.

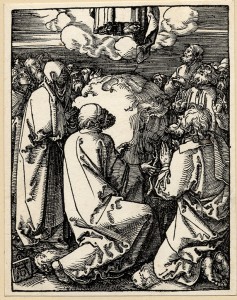

Saint Sebastian Tied to a Tree

c.1501, print by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

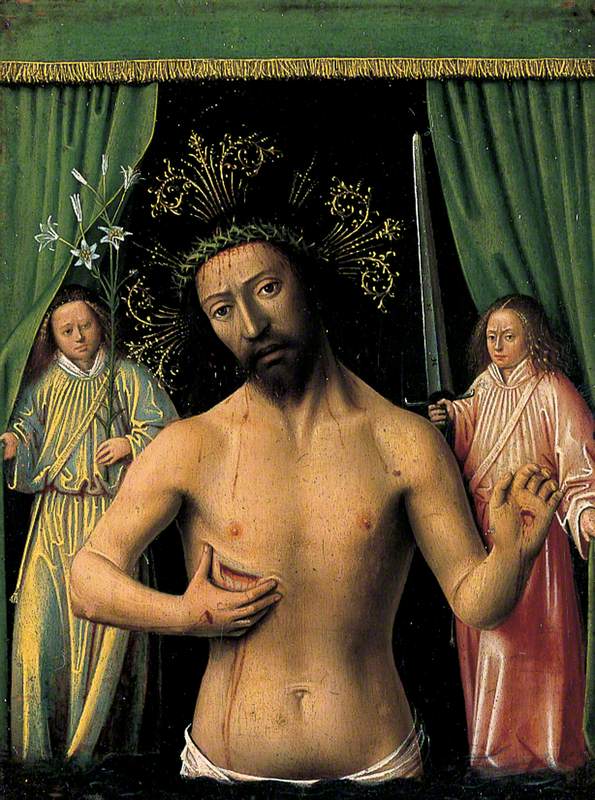

During the medieval era, Saint Sebastian was presented as a mature and manly figure. He occupied an important place in the medieval mind, and symbolised the divine protector against the plague, alongside the archer god Apollo. After the Black Death ravaged Europe in 1347, his image evolved into a youthful, healthier-looking being rather than an elderly man.

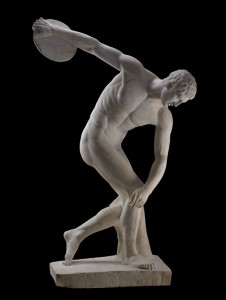

Artists of the Italian Renaissance rejected earlier depictions of Saint Sebastian, in which he appears older. Instead, they favoured depictions of masculinity deriving from ancient Greece, embodying ideals of ephebic beauty.

Subsequently, Sebastian has frequently been depicted as a handsome young man with a perfectly sculpted body. He is nearly always naked, his modesty barely covered by a thin loincloth.

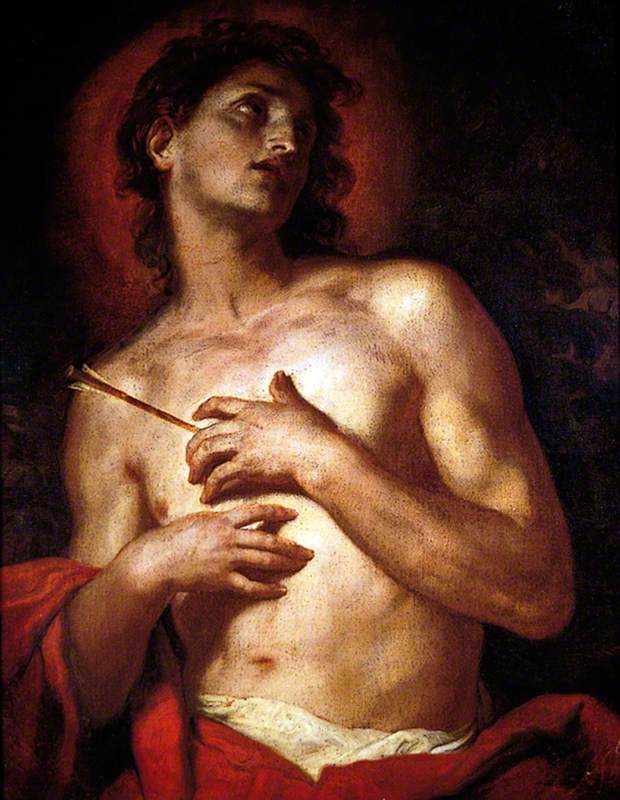

In true Christian-Stoic fashion, Sebastian does not cry out in pain as his body is pierced by the arrows but looks off into the distance or towards the heavens with an enigmatic expression.

In this sculpture by the Master of the Furies, we see a rare example of an emotional and panicked Saint Sebastian which follows in the Hellenistic tradition of portraying extreme emotion.

Saint Sebastian

c.1600–1700, ivory & kingwood socle statuette by Master of the Furies

Sebastian's typically ambiguous expression can be understood in several ways. There is at the same time both conflict and peace suggested in his slightly furrowed brow, the gentle twist of his body and slightly parted lips.

Sebastian has often been depicted as emblematic of the pleasure and pain dichotomy within Christian martyrdom – that is, that one must endure 'pain' on earth in order to receive the 'pleasure' of eternal salvation. There is also a sense of longing in his gaze, whether this is for his future sanctification, the earthly life that he is leaving behind, or both, is unclear.

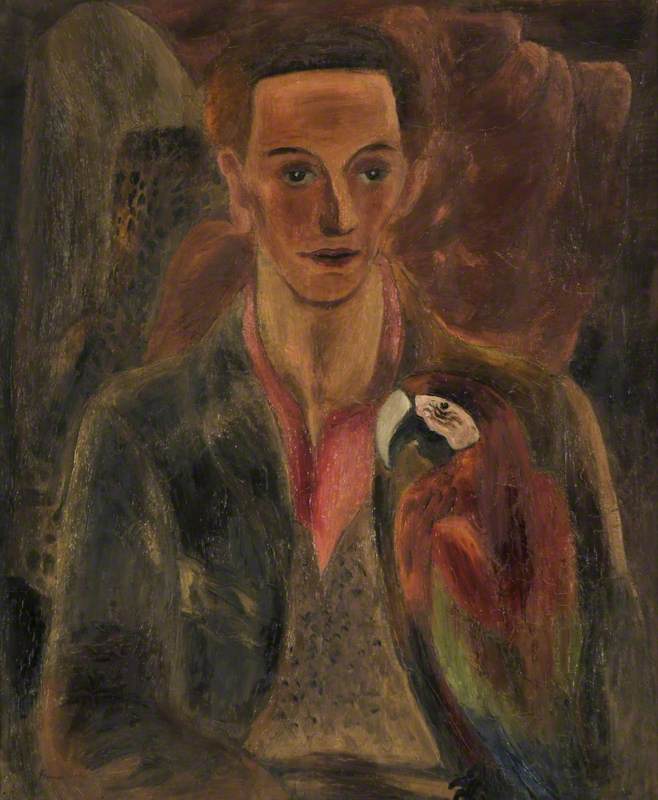

In more recent interpretations, the Christian fixation with the desirable bodies of its saints and the permeable boundaries between the bodily flesh and the divine have been seen as homoerotic or queer. Scantily clad paintings of Saint Sebastian can be understood as inviting voyeurism to the beautiful male nude.

In some instances, Sebastian's head is thrown back in supposed pleasure, making the presence of ropes and restraints positively sadomasochistic.

Some have even interpreted Sebastian's persecution as a sort of coming-out narrative, in which the martyr reveals his true self and is punished for it.

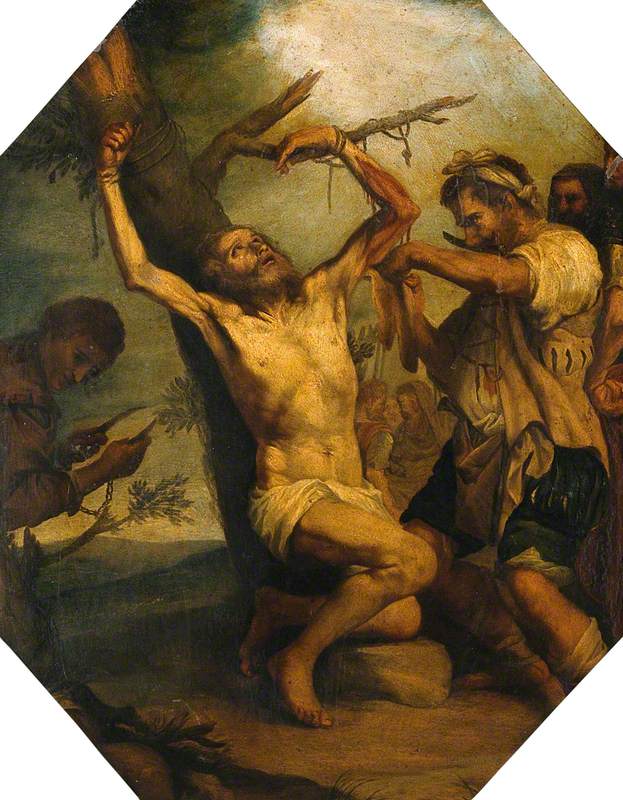

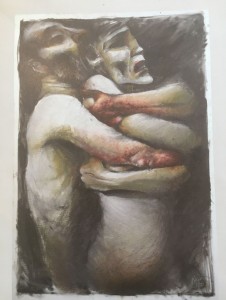

The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian

17th C

Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652) (follower of)

In 1976, Derek Jarman appropriated the traditional story of Saint Sebastian through a queer lens in his homoerotic historical thriller film Sebastiane. The film sexualises Sebastian's torture, as he demands increasingly violent thrills and displays clear erotic pleasure as he is penetrated by the arrows.

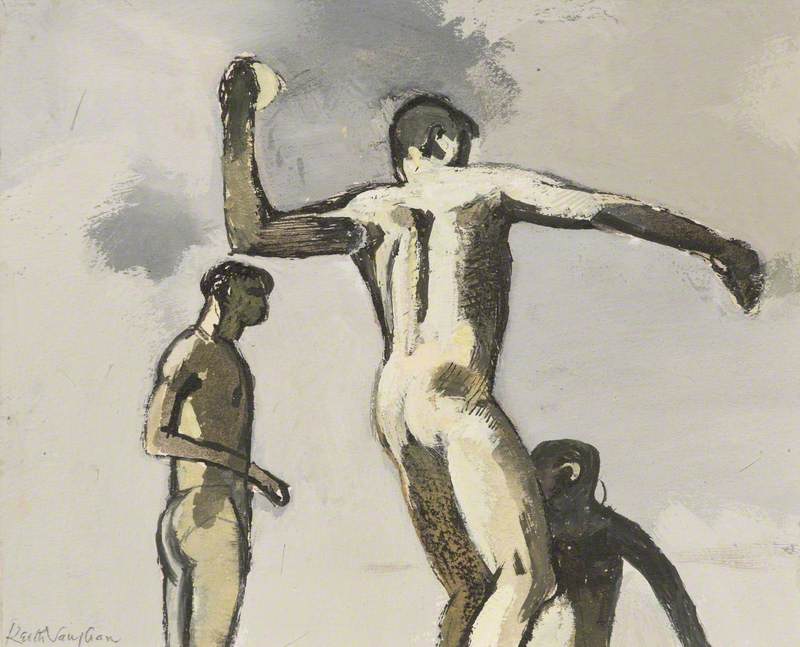

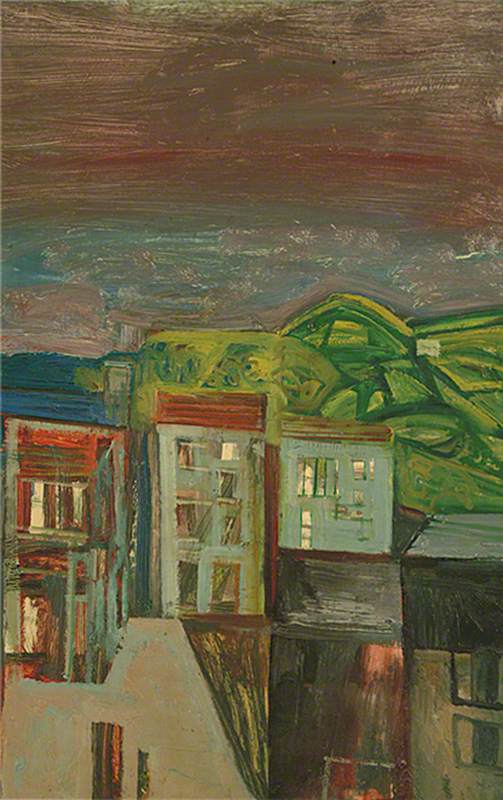

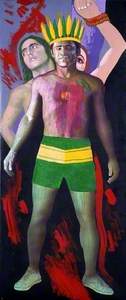

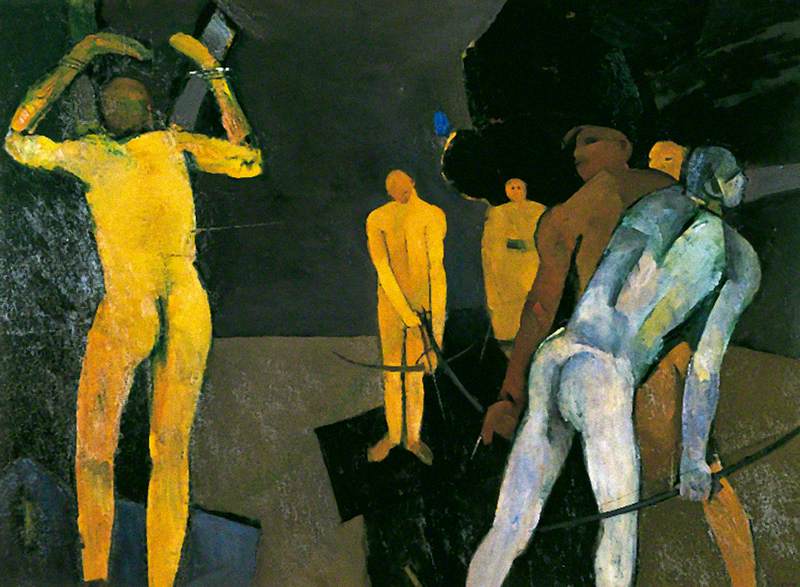

British painter Keith Vaughan (1912–1977) also made use of the myth of Saint Sebastian to express and explore his homosexual desire, a common theme throughout his work.

The yellow and white hues of his painted figures are reminiscent of the marble statues of antiquity, and the dark greens and blues reflect the sombre moment of the martyr's death. The naked archers line up to take their shot at the exposed figure who stands in an erotic pose with his back to the viewer.

The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian

1958 or before

John Keith Vaughan (1912–1977)

Euan Uglow (1932–2000) considered the upset boundaries of Sebastian's body in another way. In his rendition of Saint Sebastian, Uglow presents an apple punctured by toothpicks.

The soft flesh of the fruit is brutally pierced by the sharp sticks, but the apple maintains its structure despite this. Uglow was particularly interested in exploring contradictions in form through his work and the contrast between soft and hard in Saint Sebastian's martyrdom fits well with this theme.

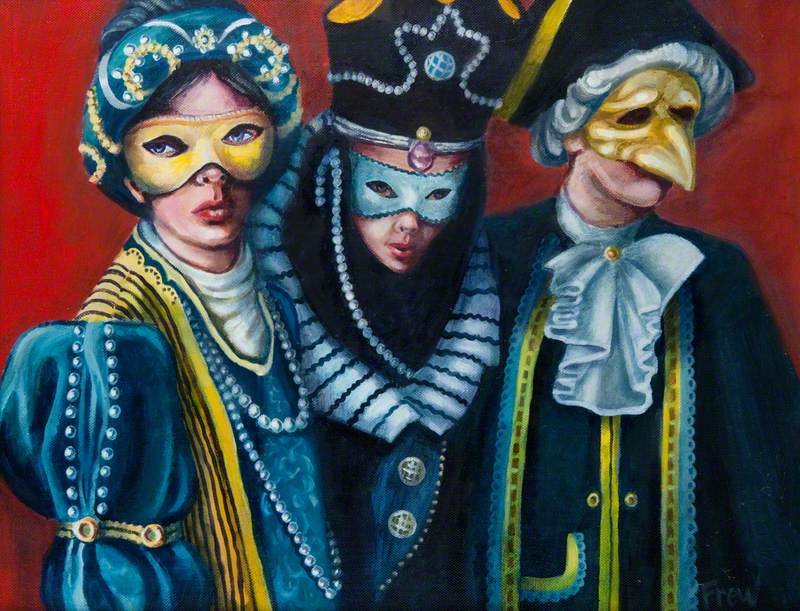

Finally, in Saint Sebastian in June by Glauco Otavio Castilho Rodrigues, we see the martyr's image used in a thoroughly modern context.

Saint Sebastian is the patron saint of Rio de Janeiro where the biggest carnival in the world is held every year. In this painting, a fit young man is dressed in beach attire in the colours of the Brazilian flag, presumably enjoying a party.

A crying figure bound with rope at the wrist and a topless man looking off to the side is reminiscent of traditional paintings of Saint Sebastian. However, in this instance, splashes of red paint – resembling spilt blood – fill the background.

Rodrigues often questions Brazilian social and political events and narratives in his work, and there is undoubtedly a stark contrast between the lively atmosphere of carnival and the gruesome death of the host city's pious saint.

The dichotomy between pain and pleasure, the violated boundaries of the human form and the saint's inscrutable expression lend the dramatic narrative of Saint Sebastian's martyrdom to a myriad of different interpretations and iterations.

Flora Doble, Operations Officer at Art UK