Mary and Joseph of the school Nativity play or the Christmas card make for an affecting image of new parenthood.

In a similar vein, they show off their special son, now an infant, in Murillo's painting The Heavenly and Earthly Trinities. Mary gazes adoringly at Jesus, while Joseph, the proud father, invites the spectator to admire his special son. But Murillo's is far from typical of the many depictions of Joseph through the ages.

The Heavenly and Earthly Trinities (The Pedroso Murillo)

about 1675-82

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617–1682)

As the Bible tells us, Joseph was a foster parent in a very unequal relationship: Mary was impregnated by the Holy Spirit. Even if a chance at paternity had come his way, Joseph would have been unlikely to perform that function, being much older than Mary – as old as 90, according to some early accounts. Joseph's last appearance in the Bible is when Jesus is 12 years old, and his own death is not reported.

In art, Joseph can appear as a grey-haired old dodderer, a bit of a spare part, or a servile figure engaged in domestic chores, not worthy of sharing the stage with his young wife and child. The far more favourable portrayal exemplified by Murillo's painting is typical of a more sympathetic and romanticised Joseph found in art in later centuries.

These different characterisations reflect a radical change in the way Joseph has been regarded in religious devotion. Until the late Middle Ages, Joseph was a minor figure who attracted mockery or disdain. Consequently, in art, he was usually present only in Nativity scenes as an elderly marginal figure. In a fifteenth-century Sienese Nativity scene, now in Oxford, Joseph cannot keep awake to share with Mary the joy of their newborn son. Even the donkey appears to take more pleasure in the child than slumbering Joseph.

Seeing Joseph as a humorous figure emphasises his humanity and endears him to us as a man struggling with the challenges of domestic life.

The change in Joseph's fortunes is largely credited to the efforts of the French theologian Jean Gerson (1363–1429), who argued that Joseph deserved proper recognition as Christ's earthly father. Gerson also believed Joseph must have been younger and physically stronger than previously thought to carry out his paternal duties. Over the following centuries, Joseph's importance gradually developed, and by the seventeenth century, he was regarded as belonging among the most important saints. Artistic representations trace this long journey towards acceptance.

One of the most cruelly derisive of all depictions of Joseph is found in Hieronymus Bosch's Adoration of the Magi triptych in the Prado, Madrid. Bosch removes Joseph from the important action of the central panel, and we find him crouching under an awning, washing (or perhaps drying) nappies, looking back enviously at the Magi paying homage.

It may be difficult to accept that representations such as Bosch's could express anything other than pure contempt, but humour was very much an ingredient in the veneration of Joseph in the late Middle Ages. In fact, Anne L. Williams claims that Joseph's rise in importance 'was tied to the laughter he elicited in hymns, plays, and art as the well-meaning but unenlightened old fool'. Seeing Joseph as a humorous figure emphasises his humanity and endears him to us as a man struggling with the challenges of domestic life.

The humour to be found in the ill-matched couple – usually an old man lusting over a much younger woman – was a notable theme of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century art. Early depictions of Mary and Joseph have something in common with these satires on the folly of old age.

The Mérode Altarpiece from the workshop of Robert Campin, in New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, offers what appears to be a far more dignified portrayal of Joseph. Although he again occupies a separate wing of the triptych, here he is using his carpentry skills, drilling holes in a piece of wood. The identity of the object on which he is working is a matter of some debate. Commonly taken to be a mousetrap, another plausible interpretation is that Joseph is engaged in making a footwarmer for his young wife, an idea originally espoused by Erwin Panofsky.

Wooden footwarmers were small boxes with perforated covers which contained hot coals. They were a popular source of heat when positioned under skirts, and as a result, took on suggestive meanings. In Dutch genre paintings of the seventeenth century, their position indicated the degree of availability of the young woman depicted. With these associations, it is easy to read Joseph as an impotent old man creating an artificial fire for his young wife, in place of the natural passion a husband might be expected to elicit.

It takes little imagination to find sexual innuendo in the act of drilling holes, and contemporary slang had several woodworking expressions which referred to sexual activity. Popular plays and ballads drew further on carpentry-related puns to poke fun at old Joseph – one, as explained by Elizabeth Lev, had him 'tinkering with his tools next to a panel of the Annunciation'.

In Pieter Bruegel the elder's Adoration of the Kings, Joseph stands behind Mary in a position that accords him some dignity and brings the Holy Family closer together. Here, Joseph is evidently an old man, but he is a formidable, alert presence. And yet in this unsettling picture – full as it is with gawping, imposing figures – Joseph's fatherly composure is undermined. The wide-brimmed hat held at his waist draws attention to his redundant loins. And someone is whispering in his ear, a message thought to be some sort of gossip questioning the true paternity of the Christ child.

The Holy Family and Saint John the Baptist

probably 1620-5

Jacob Jordaens (1593–1678)

Half a century later, Jacob Jordaens's The Holy Family and John the Baptist brings the family together in what looks like a posed photograph. Mary holds up her fleshy son for the camera and the infant John the Baptist squeezes into the shot. At the back, we find Joseph, virile and brooding, a far remove from Bosch's abject old man. And yet we detect a haunted look, a face darkened by troubles. Although this is a rehabilitated Joseph – no longer the pathetic outcast – he seems uneasy, still unable to enjoy the role of the family man.

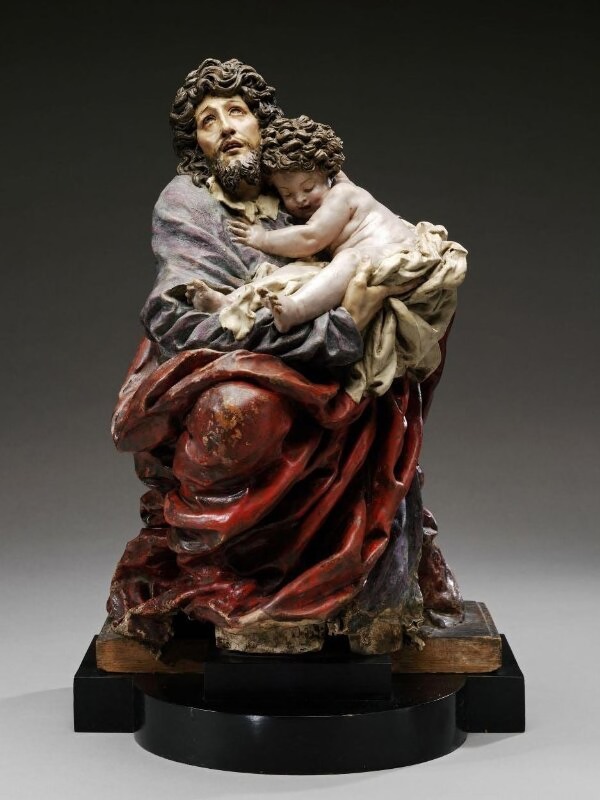

By the eighteenth century, Joseph is deemed worthy enough to take charge of the Christ child without Mary. In works by José Risueño and Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, he takes over Mary's time-honoured role with full fatherly confidence and pride. By this time Joseph had become firmly established as a subject of devotion in the Catholic church, and it is even claimed that as Joseph's star rose, that of Mary actually declined.

Saint Joseph with the Christ Child

1767

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770)

Joseph's rehabilitation was further affirmed by two more telling artistic responses. In some seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Spanish and Mexican works, Joseph was depicted with the adult Christ's physical features, suggesting a strong family resemblance, indicative of a biological relationship. A handsome, dark-haired, trim-bearded Joseph is a far cry from the grey-haired old man of earlier art, and the suggestion of natural paternity gives Joseph a greater status and authority as paterfamilias.

Other images of the Holy Family are akin to genre scenes, in which Mary and Joseph are engaged in everyday domestic duties, bringing them closer to the humble lot of the devout beholder.

The Holy Family with a Little Bird

1650, oil on canvas by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617–1682)

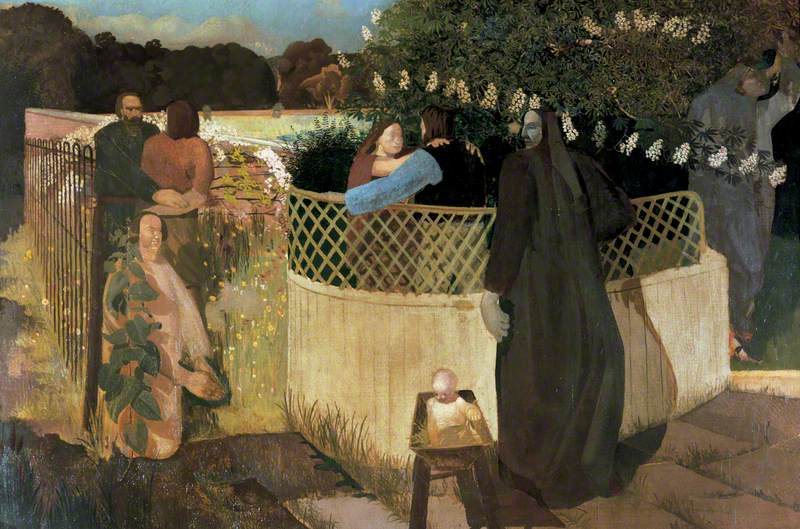

Stanley Spencer's eerie nativity scene harks back to earlier times when Mary was firmly centre stage and Joseph in the wings. But Mary, a forbidding figure with leaden face and hands, seems distracted as she turns away from her baby towards two pairs of figures in what appears to be a domestic flower garden. Spencer's scene is informal and compositionally strange. Joseph has wandered off to the right and is, according to Spencer himself, 'doing something to the chestnut tree'. This separation contrasts with the affectionate embrace of the pair behind the trellis, emphasising the difference between the intimacy of an ordinary human relationship and the spiritual burden of the ill-matched Holy couple.

Joseph's status reflects the contradiction that the devout must reconcile: Jesus was both a man and God incarnate. Joseph was therefore required to complete the picture of a normal earthly family. But the special nature of his duty meant that a young, virile man would not do. As Anne L. Williams puts it: 'he needed to be old and chaste, so that Mary might remain pure in the eyes of all'.

When the murderous threat of King Herod was made known to Joseph in a dream, he took his family away to safety in Egypt. Maintaining the appearance of an ordinary family helped to keep Christ, at least for the time being, safe from harm.

The Rest on the Flight into Egypt

c.1580–1620

Giovanni Battista Paggi (1554–1627)

To modern minds, the story of Joseph can serve quite different agendas. Some see the fact that Mary conceived without the help of a man a model of female independence that challenges gender stereotypes. Others find that Joseph speaks to the idea that loving and effective fatherhood is not dependent on biological paternity, and that Joseph's example of selfless and unquestioning devotion to his family – despite its unique challenges – is a supreme example of human love.

What the art of Joseph shows is that he emerged from his early peripheral and comedic portrayals to assume the place his resurgence demanded – an important figure alongside Mary and Jesus – with artists giving him the dignity and vitality that seemed only fitting.

Adam Wattam, writer

Further reading

Charlene Villasenor Black, Creating the Cult of St Joseph, Princeton University Press, 2006

Elizabeth Lev, The Silent Knight: A History of St Joseph as Depicted in Art, Sophia Institute Press, 2021

Anne L. Williams, Satire, Veneration, and St Joseph in Art, c.1300–1550, Amsterdam University Press, 2019

Anne L. Williams, 'Satirizing the Sacred: Humor in Saint Joseph's Veneration and Early Modern Art', Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 10, no. 1, 2018