The varied depiction of men's neckwear in British art history from the sixteenth to the early nineteenth century tells us a lot about male identity through the ages. From the Elizabethan ruff to Georgian cravats, long before the recognisable tie and collar emerged in the nineteenth century, what do these symbols of male power say about wider developments in society?

Taking up space

Let's start with neckwear at its boldest: the startling standing collar and ruff of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Originating from a fairly modest neckline frill, the excessive Elizabethan ruff from the mid-sixteenth century onwards was supported by heavy starch and wire. Often very large in size, the ruff is more than an opulent aesthetic accessory that frames the face – it occupies and holds space.

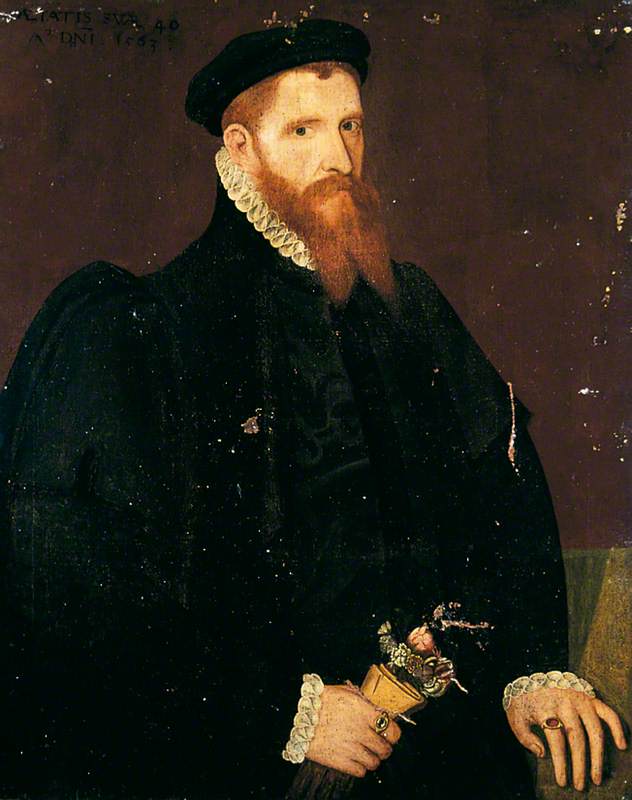

Take the image of Sir Arthur Slingsby, who belonged to the aristocratic Slingsby family in the north of England, pictured here in the late Elizabethan style. His apparent stoicism sits alongside youthful determination and conceit. Or perhaps insecurity – look at how the artist highlights the flush of his cheeks. Yet while the face tells one story, the collar tells another.

Slingsby's impractical, high-maintenance ruff immediately communicates status and wealth. He obviously amasses enough money to access the many resources needed to make this collar – he has the luxury to afford aesthetic discomfort and to quite literally take up space.

Image credit: The Hepworth Wakefield

Portrait of a Gentleman with a Lace Collar c.1660–1670

Jakob Ferdinand Voet (1639–c.1700)

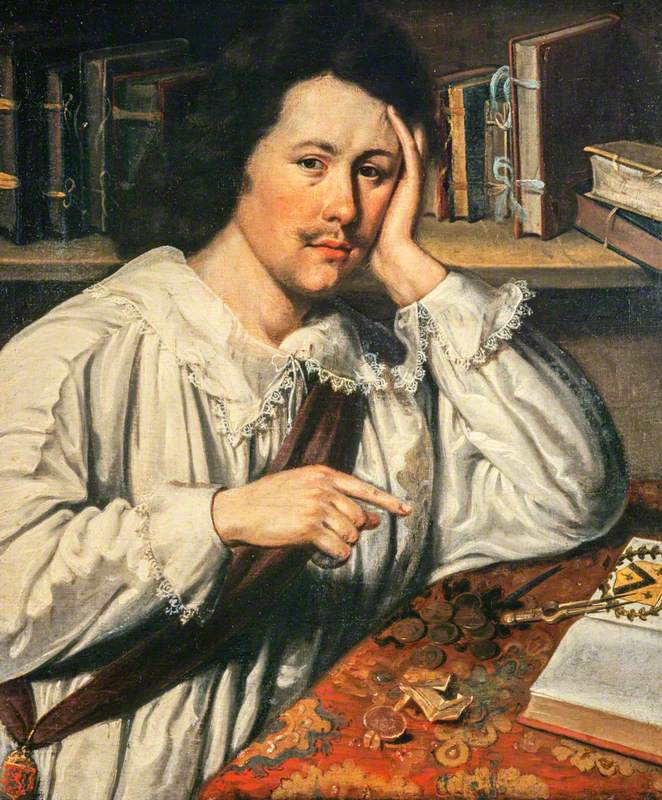

The Hepworth WakefieldPortrait of a Gentleman with a Lace Collar (c.1660–1670) by Jakob Ferdinand Voet carries this narrative forward a century. A youthful face seeks out the viewer, lost almost by a cascading wig and equally dominant soft lace cravat, made fashionable in the seventeenth century and symbolic of exceptional wealth.

At this time, male status was determined by wig size and so the cravat overtook the earlier trend for falling collars – shown here in a portrait of Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick by Daniel Mytens – that hung over a wearer's shoulders so that the collar could be seen more clearly.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Robert Rich (1587–1658), 2nd Earl of Warwick, Aged 45 1633

Daniel Mytens (c.1590–1647)

National Trust, Hardwick HallWhat's more, male power-play is clear in these new forms of extravagant fashion that (consciously or unconsciously) reference phallic size and potency. A case of 'mine is bigger than yours' perhaps?

Unbuttoned and 'the romantic'

A loose, unbuttoned collar in art history is equally as charged as a rigid ruff. To show your neck in a culture that expects it to be covered is most likely a conscious act, and a vulnerable one at that. Such uncovering was not the norm that it is now and its depiction in art can signal male emotion, sensitivity and even desire.

Take the 'romantic hero' Lord Byron, depicted here in one of his most famous portraits by Thomas Phillips from 1813.

While his contemporaries are often covered up in stiff cravats and Regency collars – see Thomas Lawrence's portrait of Humphry Davy, for example – Byron chooses a soft collar, open to reveal his neck and giving him an air of deliberate undress. The rest of his clothes say little so that the pearl-white shimmer of the collar immediately draws our attention.

Writer, poet, aristocrat, scholar, solider… lover. Byron's social infamy is arguably worn around his neck. Byron is depicted as unbuttoned, available, unbound from rigid social conventions and as darkly gothic and sexual as his writing. The perception of Byron as transgressive, passionate, and 'free' – which he himself cultivated – is supported by the collar he wears.

In terms of fashion, Byron's neckwear sits within the Georgian era but references earlier Elizabethan styles; the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries saw the appearance of softer ruffs and low-cut necklines – the latter clearly visible in Marcus Gheeraerts' Portrait of Captain Thomas Lee (1594).

The same unbuttoning device shown in Byron's portrait can also be seen in Portrait of a Man, dated between c.1590 and c.1625/1635. No less curated in appearance than Byron, the sitter's loose lace collar invites an intimacy with the viewer.

Wearable power – spiritual, political and colonial expressions

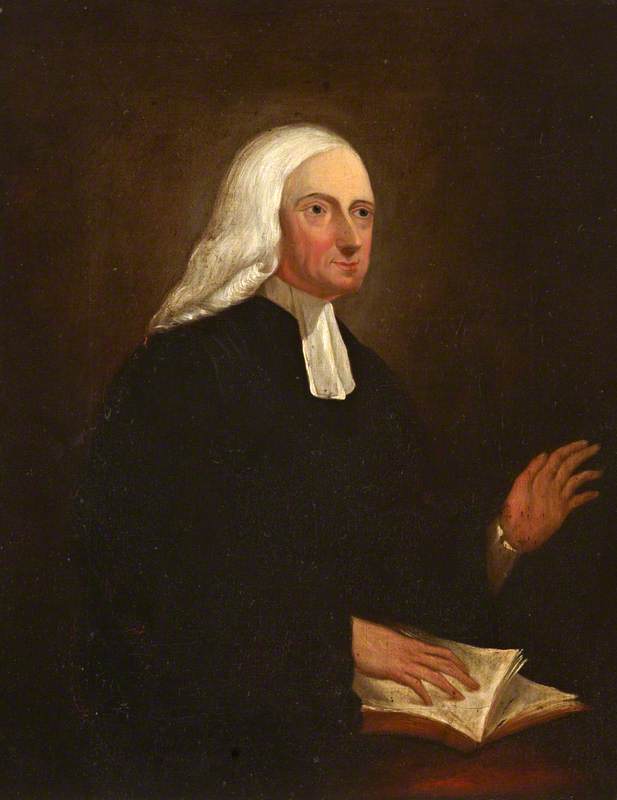

Just as power and emotion can be conveyed via neckwear, so too can morality, faith, and notions of virtue. Eighteenth-century cleric and evangelist John Wesley's image proliferated in part because of his role as a founder of Methodism. An image of Wesley, made after his death, captures him engaging with scripture.

Image credit: John Wesley’s House & The Museum of Methodism

John Barry (active 1784–1827) (after)

John Wesley’s House & The Museum of MethodismSimple in its style, this work references Wesley's humble origins. The face is full of character – experienced, flushed with passion and feeling, his large open eyes reaching beyond us. Yet it's the collar that is central to the composition.

This archetypal image of Wesley features his white hair, black robes and preaching bands – what we would recognise today as the clerical 'dog' collar. The primary function of a collar such as this was to signal a person devoted to a life of faith and pastoral care. Wesley, famed as a travelling preacher, wears the eighteenth-century version of the collar to transmit a clear message about his role as a clergyman and that he was well-educated – but also that faith is something easily worn.

Neckwear also speaks to civic as well as spiritual power. Charles II is lavishly depicted here by Peter Lely around 1680 – towards the end of his reign. The king is pictured wearing a lace cravat, which is symbolic in a number of ways. The cravat emerged in France during the seventeenth century, inspired by the neckwear of Croatian soldiers who had been enlisted by Louis XIII to fight against the Habsburg Empire. When Charles returned to England in 1660 to restore the monarchy after nine years in exile at the French court, he brought the cravat trend with him.

Image credit: Winchester City Council’s Topographical Art Collection

King Charles II (1630–1685) c.1680

Peter Lely (1618–1680)

Winchester City Council’s Topographical Art CollectionFrench fashion and court culture had a huge influence on Charles – and in Europe more broadly at this time. His mother, a French princess, was a direct link to French court politics as was one of his mistresses, Louise de Kéroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth. During his reign, Charles forged strong ties with France: in 1670 he signed a secret treaty with Louis XIV in which England offered aid in a war against the Dutch, as well as a promise to return the country to Catholicism. The cravat clearly operates here as a potent political symbol.

Neckwear in art history can, however, have more disturbing connotations. The painful legacies of colonial power are made clear in this troubling image by Johann Verelst entitled Elihu Yale with Members of his Family and an Enslaved Child (c.1719).

Alongside depicting the British American colonist Elihu Yale and his sons-in-law, all wearing long white collars, the painting also features a young unidentified figure of African descent wearing a metal collar padlocked around his neck. Neckwear here is literal injustice, a brutal sign of enslavement and possession.

A queer collar indeed

Art history is full of extravagant, ostentatious works that, from a contemporary queer perspective, play with ideas around identity and gender expression.

Dr Nathaniel Spry, Aged 45 (1703) by B. Burghende is lavish and over-the-top, a swirl of satin and hair. His necktie is full and flowing. Would some today consider Spry's appearance to be feminine? Spry is seen here in the height of fashion that would not have been read as 'feminine' by his contemporaries. We look differently at this work from our contemporary viewpoint.

Elsewhere, take this eighteenth-century image of the English courtier John Hervey, 2nd Baron Hervey by John Fayram, wearing a well-appointed necktie and draped in a sumptuous silk shawl. Hervey was open about his sexuality, enjoying both a relationship with his wife Mary Lepell and (as discovered in his correspondence) with a man called Stephen Fox. Today we would perhaps consider him bisexual.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Lord John Hervey (1696–1743), 2nd Baron Hervey of Ickworth, PC, MP c.1737

John Fayram (1690–1744)

National Trust, IckworthHervey played with gender expectations and was seen as effete in his own lifetime. Here the Queen's favourite courtier appears androgynous despite the masculine neckwear – perhaps in part due to his liberal use of face powder.

Ideas of neckwear as rigidly gendered, as male and female, are not supported in art history. Just as the ruff was worn by men and women, for example, so too was the cravat and scarf.

Throughout art history, the neckpiece is used as a visual building block to tell a story about male identity, acting as a political, religious or sexual symbol. A small, seemingly inconsequential lace cravat in fact says a lot about power, status and wealth.

Jon Sleigh, freelance arts educator

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation