Modern British art is a term that refers to the art made in Britain in the first part of the twentieth century, when mammoth changes in human life and experience such as the dawn of the machine age, the violent upheavals of two world wars and political extremism in Europe combined with a burgeoning engagement with modernism in the visual arts, literature, poetry, theatre and music.

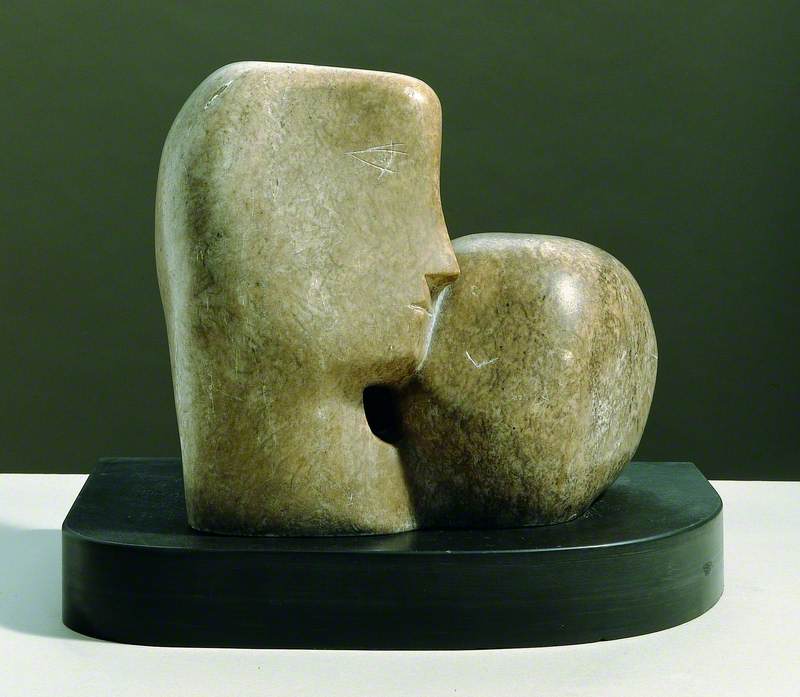

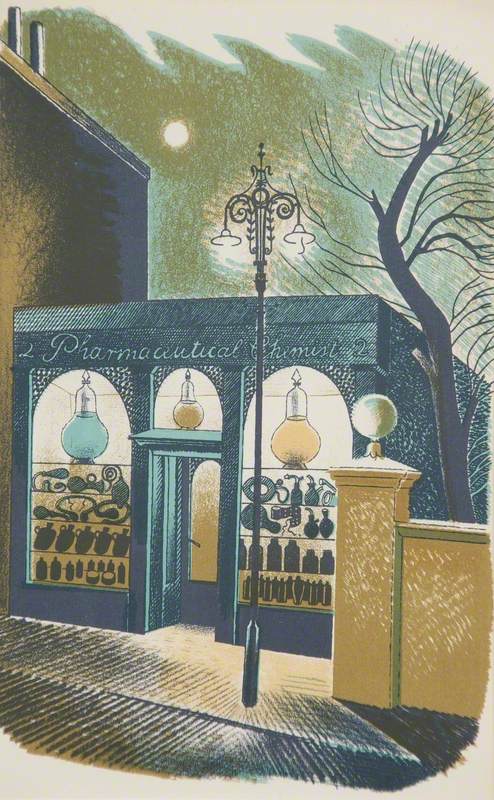

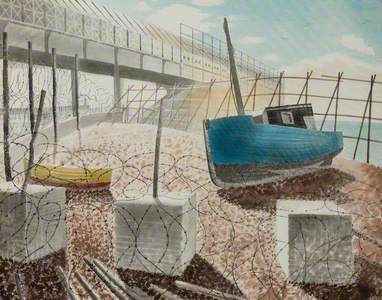

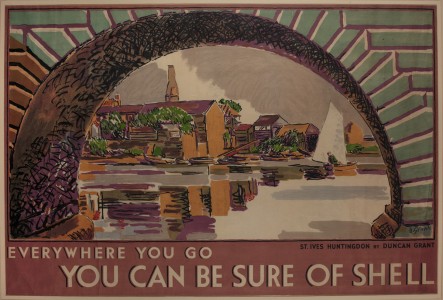

The art created in Britain during this time – and by artists who were not necessarily born in Britain – has become part of our national visual culture. The exquisite abstraction of Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson, the quintessential Englishness of Eric Ravilious's eerie watercolours, the 'You Can Be Sure of Shell' campaign creating commissions for hundreds of artists in the 1930s, and Henry Moore's monumental sculptures sited around the country have created an accepted story of modern British art.

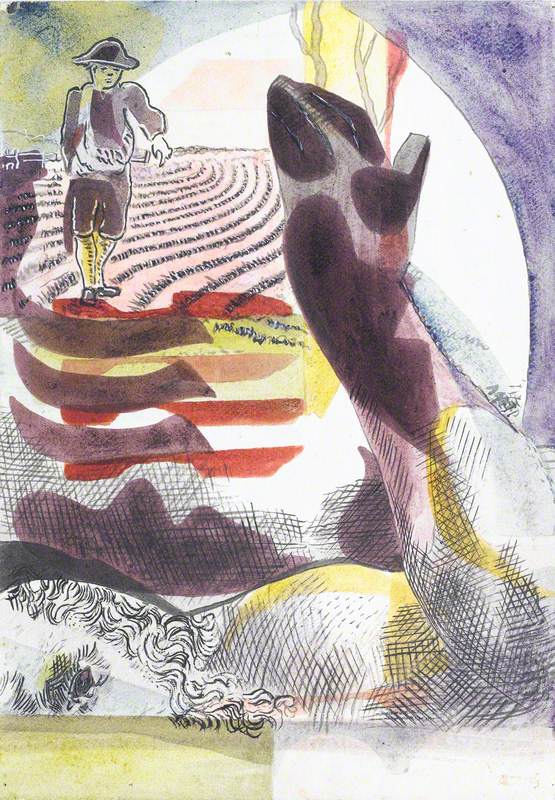

Shell Poster, St Ives, Huntingdon

c.1930

Duncan Grant (1885–1978)

This narrative has rarely been questioned, and it is only very recently, with exhibitions such as Tate Britain's 'Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950s–Now' (December 2021 – April 2022) that our major cultural institutions have begun to reassess those artists who have been excluded from the official narrative of countless books and museum trails.

I have been working in the field of modern British art for over twenty years and in that time I have seen a huge increase in interest and appreciation for the period. Although many museum directors and curators have done invaluable work showcasing the work of artists who had been forgotten (Edward Burra at Pallant House Gallery, October 2011 – February 2012 is a prime example of this – Burra's draughtsmanship, idiosyncratic compositions and subject matter were revelatory), there is still much to be done. With this in mind, I have spent the last few years working on and editing the book Revisiting Modern British Art.

This book is a celebration of modern British art, which highlights the beauty and range of the works created, whilst also pulling out new threads and asking different questions. Introduced by James Russell, it is comprised of twelve essays from different writers, curators and art historians, each of whom brings a fresh perspective. It seeks to show how an engagement with the contemporary moment can bring about refreshed empathy and insight into the art made on these islands in the previous century.

In her essay, Alexandra Harris (author of Romantic Moderns, 2010, and Weatherland: Writers and Artists under English Skies, 2015), explores 'loss and living on' after shared trauma and tragedy. Writing in the 'preternaturally fine spring of 2020', Alexandra guides us towards renewed perspectives on the work of artists such as Stanley Spencer, Henry Lamb and David Jones in her lyrical evocations of art, war and resurrection.

Laura Freeman (chief art critic of The Times and author of the forthcoming Ways of Life: Jim Ede and the Kettle's Yard Artists, Jonathan Cape, 2023) looks at the art of the home during the Second World War, and how 'for reasons of war, petrol rationing, restrictions on travel abroad and economic depression, once broad horizons narrowed and drew inwards'.

The themes within this chapter chime with our own strange, stay-at-home pandemic, where, as Laura writes, 'home was a sanctuary, home was a burden'. And we empathise with artists such as Barbara Hepworth who wrote to Ben Nicholson in 1942: 'I haven't done any work yet except drudgery – it just doesn't seem possible to do it under these conditions even though I'm just bursting with ideas'.

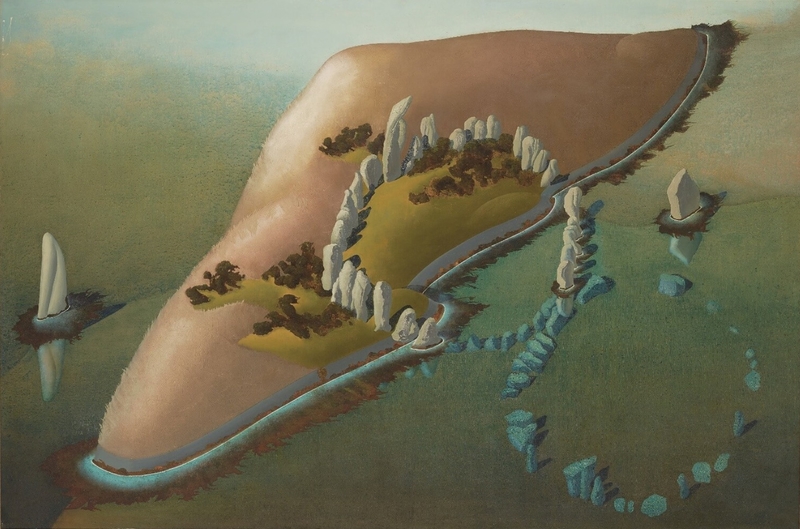

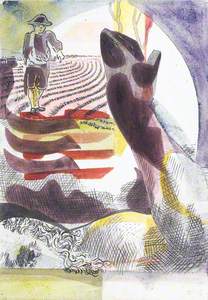

In other essays, we are shown by Laura Smith (curator of the recent Eileen Agar exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery) how the international movement of Surrealism found unique expression here in Britain, through the deep seam of engagement with landscape that runs through our culture.

The artist Paul Nash felt that the landscape here is 'full of strange enchantment' and Laura shows how landscape and the concept of the genius loci became a key part of how Surrealism was expressed in Britain. We also learn more about the women of the movement, not just the better-known names such as Eileen Agar and Leonora Carrington, but artists such as Emmy Bridgwater and Marion Adnams. They were determined to not simply be thought of as 'muses', but rather as artists with significant contributions to make.

The art historical essays in the first part of the book explore moments in the art of the century by decade, concluding with the 1960s, where Elena Crippa (Senior Curator at Tate Britain, and curator of the 2021 Tate exhibition 'Paula Rego') encourages us to think more broadly about how post-war Britain was shaped by artists arriving from overseas, and how the self-image and self-perception of a generation of young people was transformed through the 'aesthetic of abundance' of collage and mechanically produced images. This enabled artists such as Peter Blake to break with tradition and create startlingly modern works that reflected a new world.

The second part of the book examines the structures of the art world, drawing out the impact of 'backstage sponsorship' in a discussion of how and why some artists become part of a 'national' story of art while others are left out – unsupported by our official structures, institutions, curators, collectors and a highly influential commercial art world.

Readers are encouraged to question the influence of private collectors on UK museums, perhaps through an active lending policy to institutions, gifts of works during or after their lifetimes and even, in the case of collector Margaret Gardiner and the Pier Arts Centre, the creation of institutions.

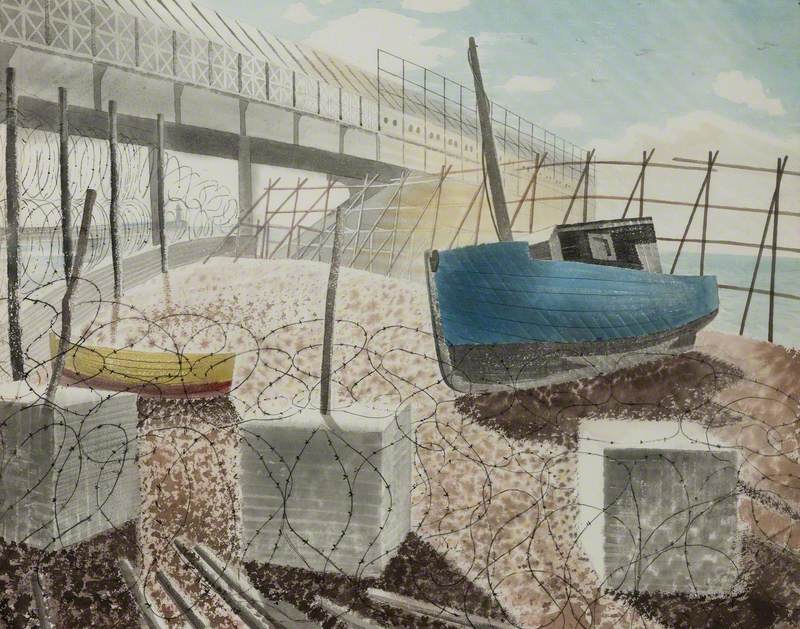

We are also invited to explore the role of corporate and government patronage on visual art in twentieth-century Britain. Dr James Purdon (Lecturer in Modern and Contemporary Literature and author of Modernist Informatics, OUP, 2016) draws out the subtleties of these 'complicated relationships' that 'helped to cultivate a taste for the varying styles of modern British painting among viewers far beyond the usual exhibition spaces or the private collection or art museum'.

His essay examines 'the deep entanglement between British modernist painting, state institutions and big business, demonstrating both how these relationships of patronage made possible the work of some of Britain's most celebrated twentieth-century artists, and how, at the same time, a 'British modern' aesthetic was deployed to influence public opinion regarding the activities of official bodies and powerful corporations'.

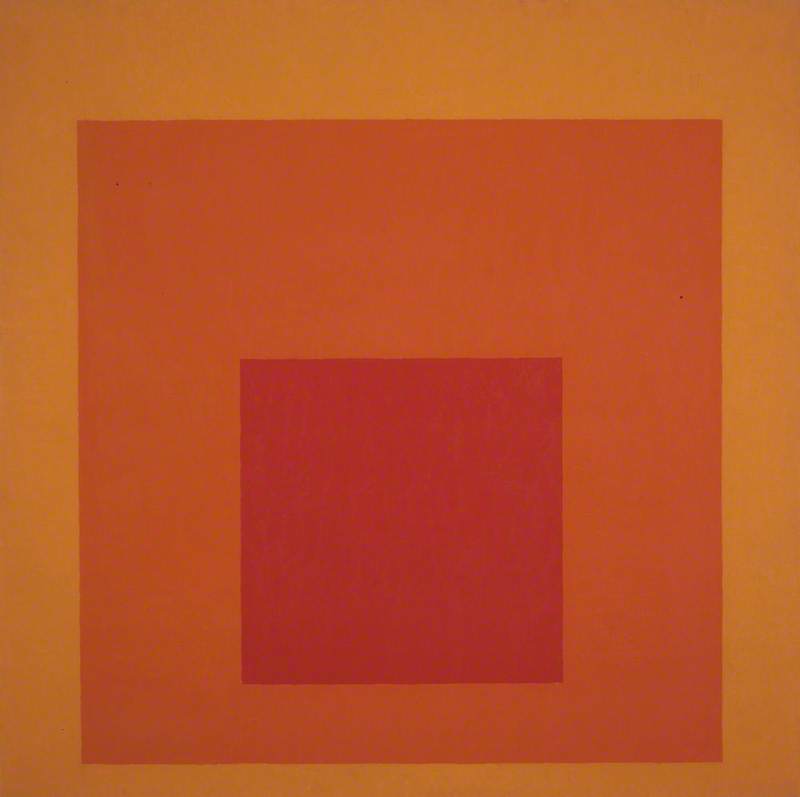

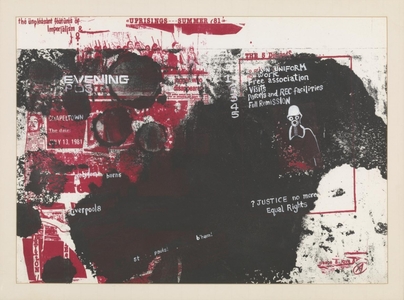

Air, Sea and Land use Shell

1936

Andrew Johnson (1893–1973)

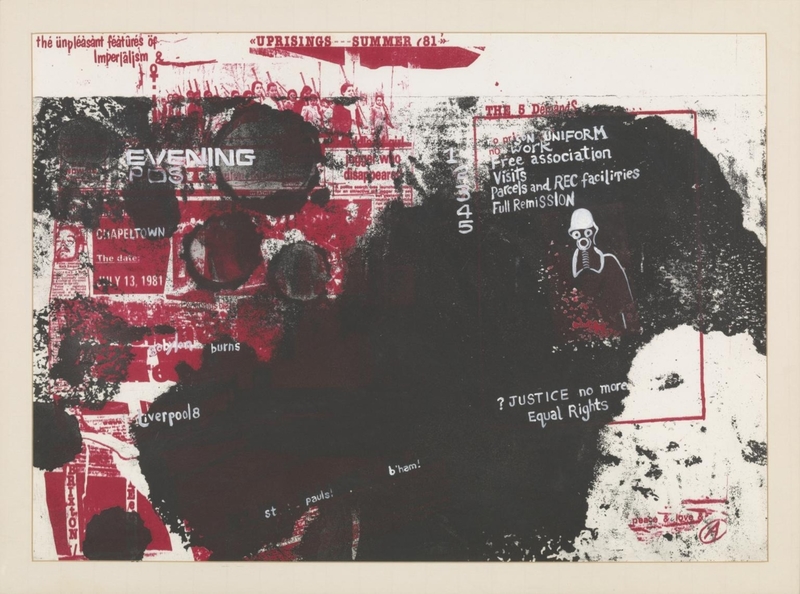

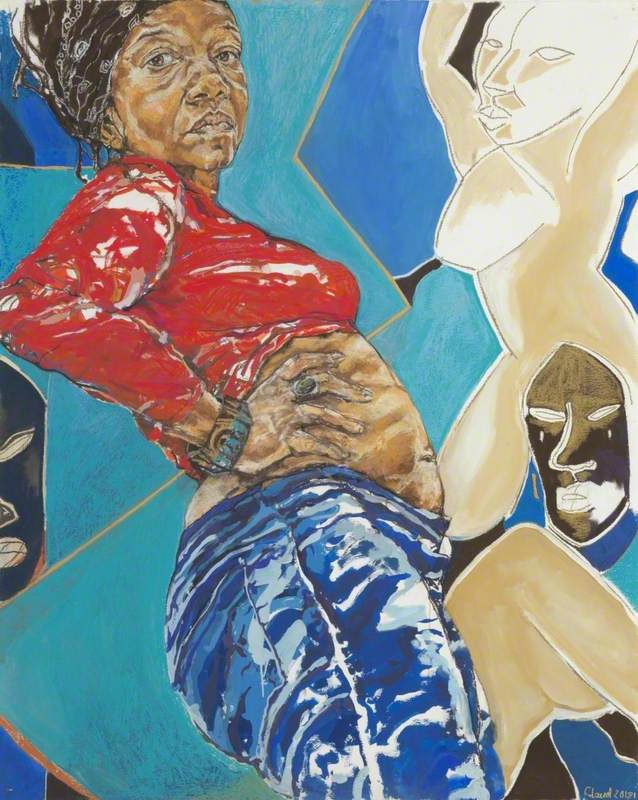

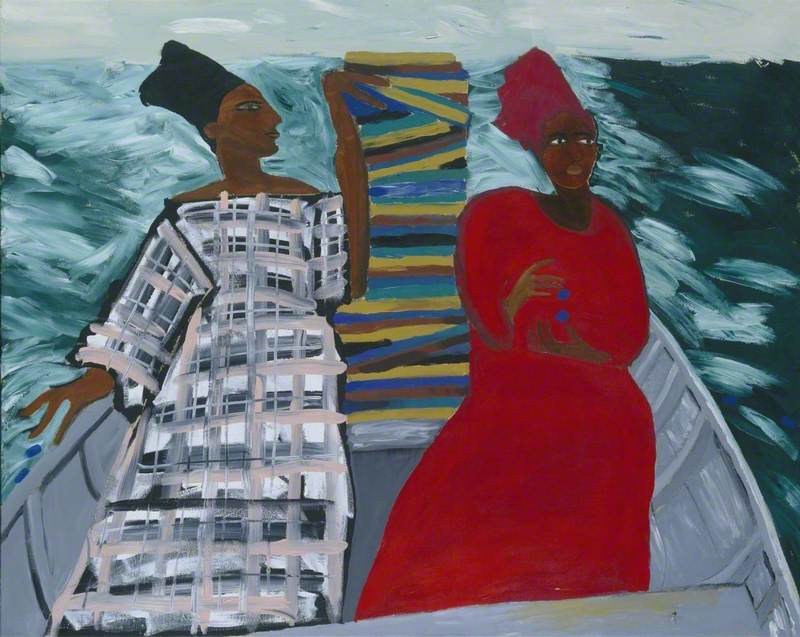

Over the course of the essays, we are asked to question the role of race, the Eurocentric nature of our art history, gender and sexuality in artistic careers and cultural construction, and how artworks are assessed – ultimately what we see on our museum walls and therefore what we have access to on websites such as Art UK.

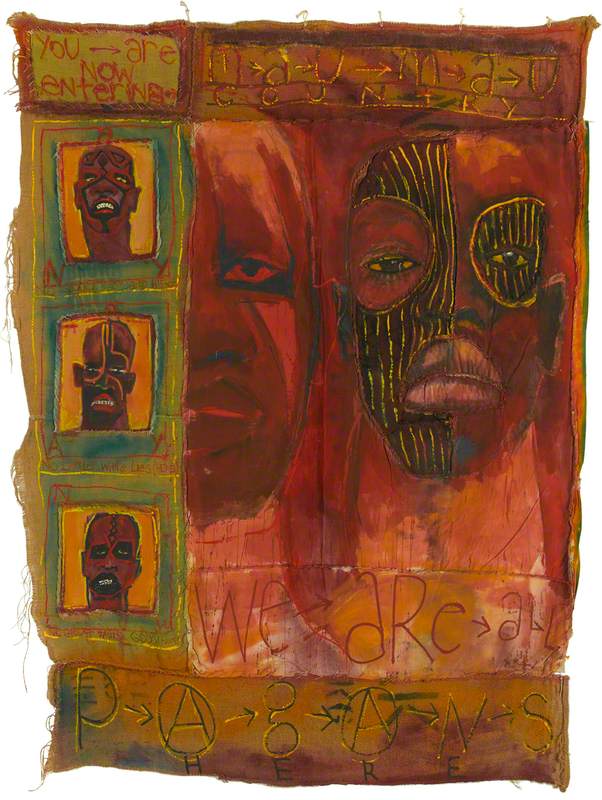

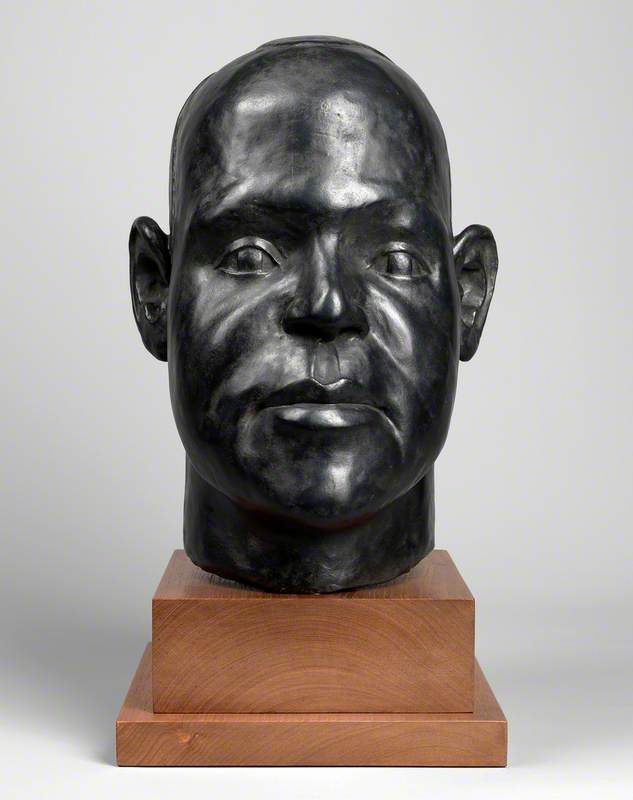

To end the book, we hear a personal call for a more expansive British art from curator and writer Aindrea Emelife. Writing as a young Black woman brought up in Britain, she asks if there really can be a common theme to art made in one place, whether or not it is still valuable to consider art in national categories, and questions, in particular, why 'nationalism has been the first and foremost categorisation'.

Artists considered here are Ronald Moody, Lubaina Himid, Claudette Johnson and Chila Kumari Singh Burman.

There is still much to learn about modern British art, much to explore and discuss. It is my hope that this book encourages readers to join the debate, to question what we see on our museum walls, the exhibitions we have access to and the stories of art history that are told.

Jo Baring, Director of The Ingram Collection of Modern British and Contemporary Art

Revisiting Modern British Art, edited by Jo Baring, is published by Lund Humphries on 10th October 2022