Inspired by the whimsical genre of French Rococo painting, Flora Yukhnovich's work offers a refreshing, contemporary twist on the eighteenth-century style of painting that speaks particularly to Millennial and Gen Z generations.

The artist regularly visits The Wallace Collection, a stately home tucked away in London's Manchester Square, which formerly belonged to the Marquesses of Hertford and named after the art fanatic Sir Richard Wallace. Still today, the house displays one of the finest collections of French and Italian Rococo art in the world, containing works by well-loved artists such as Jean-Honoré Fragonard, François Boucher, Nicolas Lancret and Jean-Antoine Watteau.

Scroll down to find out more about Flora's playful take on a genre that, in many ways, resonates with contemporary culture.

Flora Yukhnovich

Lydia Figes, Art UK: When did you begin to explore Rococo painting?

Flora Yukhnovich: During my MA I stumbled across a book of Jean-Honoré Fragonard's work. His paintings made such a strong impression on me but I couldn't work out exactly why. I began mimicking his palette and working with imagery borrowed from his paintings to try and understand them better.

I must have become attuned to the Rococo aesthetic because I began to notice it everywhere around me: in advertising, in shops, cartoons, children's toys, music videos and so on. I soon realised that most of these things were in some way targeted at women and girls.

I think that was why I found Fragonard's painting so intriguing. On one level, I enjoyed the sweetness of them but at the same time, I felt uneasy as being drawn to something so stereotypically feminine.

Lydia: Tell us more about Fragonard and the other Rococo artists who particularly influence your work.

Flora: Fragonard has remained an extremely important artist for me because of the painterly qualities in his work. For example, if you were to somehow empty The Swing (1767–1768) of its literal meaning, I think it would still have the same erotic and fleshy implications because the touch of his brush so sensitively mirrors the meaning of the work.

The surface feels like a grittier, more corporeal version of the subject matter. For me, this painting opened up another way to think about gender as it combines a stereotypically masculine way of painting with the whimsical, beauty of the scene.

An Allegory with Venus and Time

about 1754-8

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770)

In terms of the Italian Rococo, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770) is a key influence. I recently spent two months in Venice on a residency studying his work up close. I think his paintings, like Fragonard's, demonstrate that something can be decorative, yet powerful and immersive

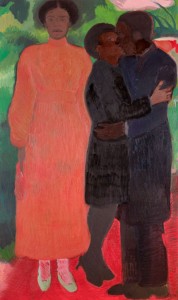

For my current show at Leeds Arts University, I have been examining the fête galantes of Jean-Antoine Watteau, Jean-Baptiste Pater, and Nicolas Lancret, considering the sexual politics at play in the genre and trying to create a more female-centric domain.

I have been looking at Francois Boucher's pastorals, for these paintings. I find puns and ambiguity very appealing so I particularly enjoy the humorous erotic subtexts of his paintings – like the milk jugs, fruit or the full basket of flowers in A Summer Pastoral (1749) for example, which could be metaphors for fertility or arousal. I have incorporated a few of these symbols in my recent paintings.

Lydia: How often do you visit The Wallace Collection?

Flora: Probably once a month. I am very lucky that one of the most extensive collections of eighteenth-century French paintings happens to be in London. The paintings hang amongst the interior decoration and design from the time, so you can really get a sense of how it might have looked.

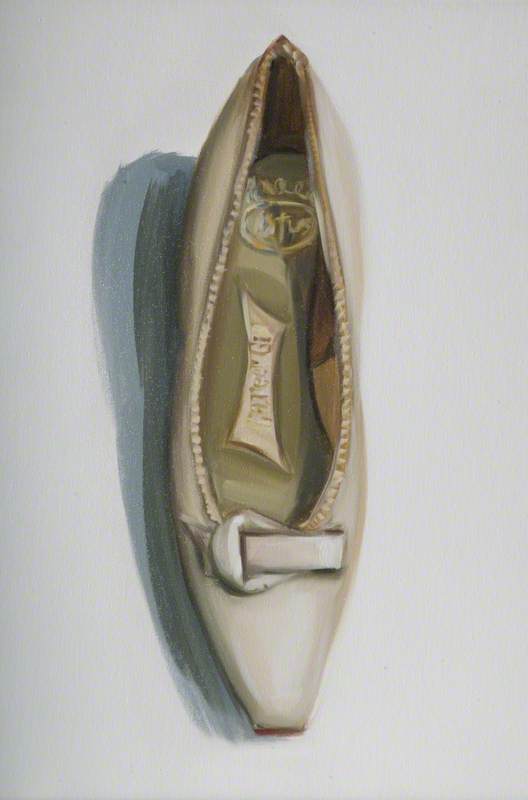

Warm Wet 'n' Wild

2020, oil on linen by Flora Yukhnovich (b.1990)

For me, the candlesticks, clocks, porcelain, wallpapers and fabrics are just as exciting as the paintings and each time I go back, I spot something new that inspires me. I usually visit before I begin a painting to restock my brain with Rococo imagery. Right now, I'm working on a painting inspired by the dress in Fragonard's The Musical Contest (1755), which somehow feels simultaneously like a piece of ripe fruit, a bloody heart or some other organ or the folds of petals in a flower bud.

Lydia: Many associate the Rococo with decadence, femininity, and frivolity – some even find it repulsive. Do you think such interpretations are often gendered?

Flora: Yes, I think so. At the time, there was a lot of female patronage and when the Rococo style fell out of fashion, women and their apparently uncultivated taste were blamed. So they were really dragged down together and now share many of the negative connotations as a consequence. Of course, there is also a vulgarity to the presentation of wealth and luxury in the paintings, which naturally still persists.

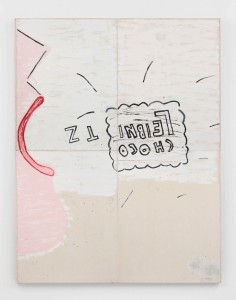

I'll Have What She's Having

2020, oil on linen, by Flora Yukhnovich (b.1990)

Lydia: What is your painting process? Do you allow for complete spontaneity or is your application of brushmark and colour more measured?

Flora: It takes me a long time to make a painting. I will often spend an entire month on a single work.

Usually, I begin with just one or two sources, then pull in different references as the painting develops, following whichever direction it leads. So I suppose it is intuitive but probably not spontaneous. Even the quicker, looser-looking marks are arrived at quite slowly.

Lydia: The titles of your paintings feel playful, almost tongue-in-cheek. Do you name a painting before or after its completion?

Flora: Sometimes a title will come to me while I'm making the work, but more often than not it's afterwards. I like the way a title can realign the tone of the piece, maybe suggesting a lighter, more humorous reading or make reference to a more contemporary inspiration for the work.

When painting, I'm always pulling together references from different parts of history or different artists. Choosing a title is just an extension of that process, allowing me to bring another fragment into the work.

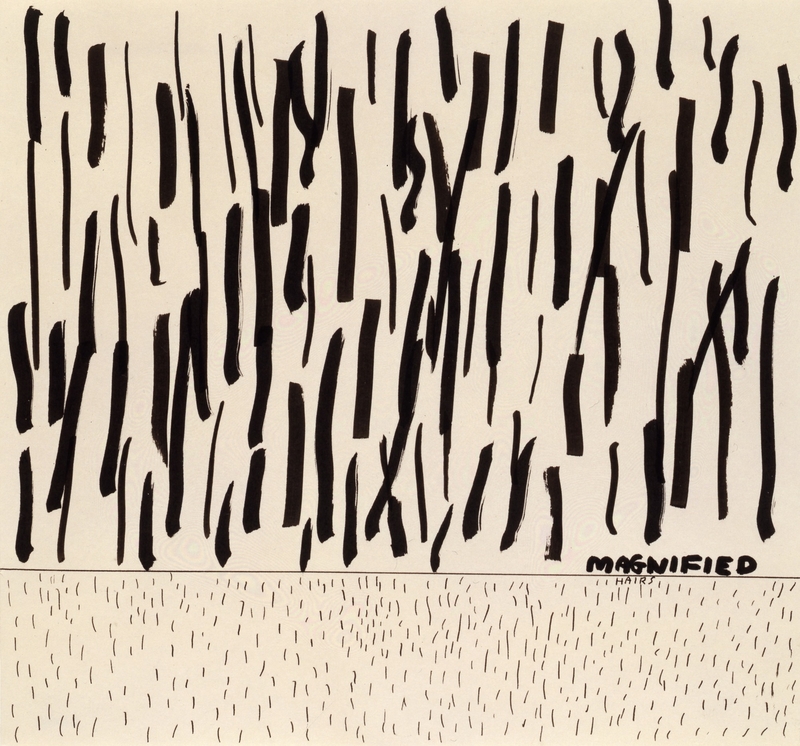

Thank Heaven for Little Girls

2018–2019, oil on linen by Flora Yukhnovich (b.1990)

Lydia: Final question: how do you think Rococo resonates in today's culture?

Flora: We live in such an image-saturated time which I think has encouraged louder and more ostentatious aesthetics that feel similar to the Rococo sensibility for excess. I also think there is something quite Rococo about our celebrity culture, and the aspirational pleasure we take in watching the glamorous lives of the super-rich on reality TV.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

To find out more about Flora's work, visit Parafin Gallery. Her exhibition 'Flora Yukhnovich: Fête Galante' a Leeds Arts University opened on 28th February and runs until 9th April 2020, although may be temporarily closed due to the Covid-19 outbreak