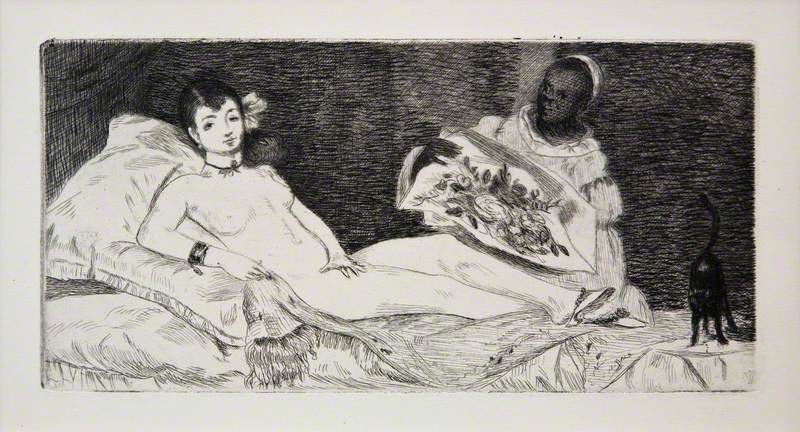

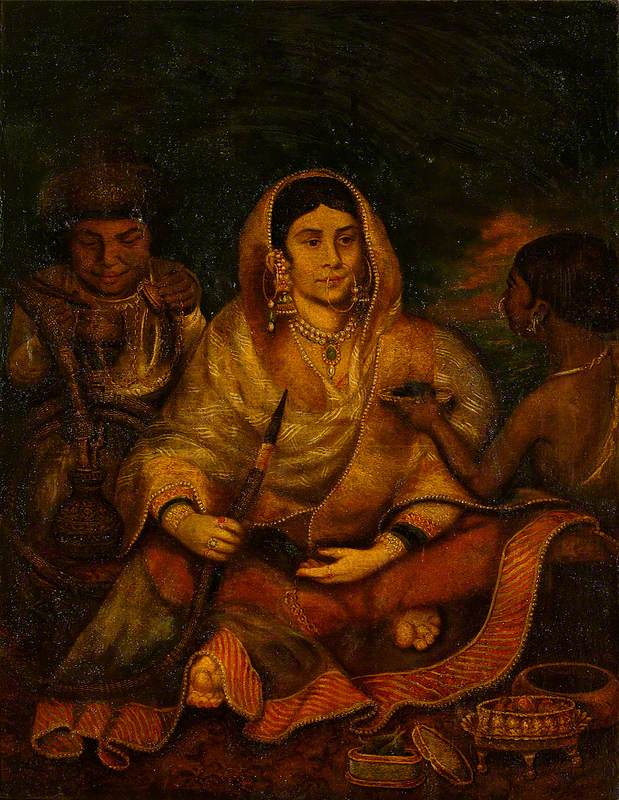

While black figures have appeared in European oil paintings for centuries, very rarely are they the subject of the scene. Instead, their presence frames their white mistresses and masters.

With the recent hyper-visibility of the Black Lives Matter movement, it feels appropriate to look critically at some of these paintings on the Art UK website and compare them with the work of contemporary artist Lubaina Himid, the 2017 Turner Prize winner whose work often gives voice to enslaved people and draws attention to the legacies of slavery.

© the artist and Hollybush Gardens. Image credit: Andy Keate

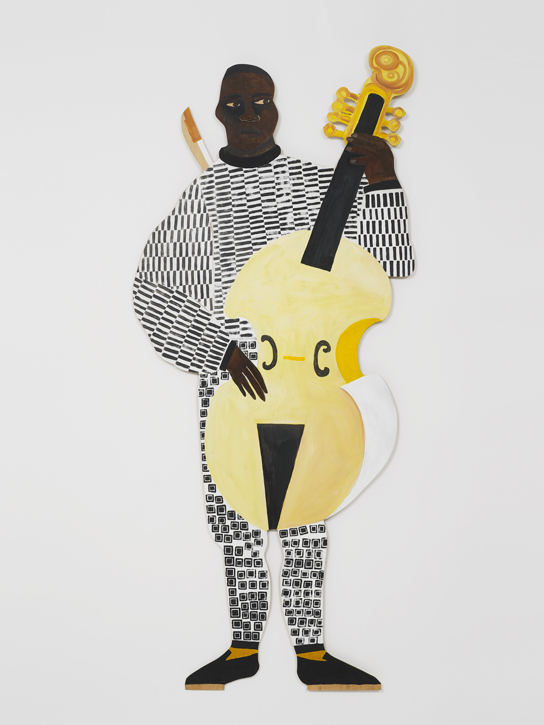

The Viola De Gamba Player (from the series 'Naming the Money')

2004, acrylic on wood by Lubaina Himid (b.1954)

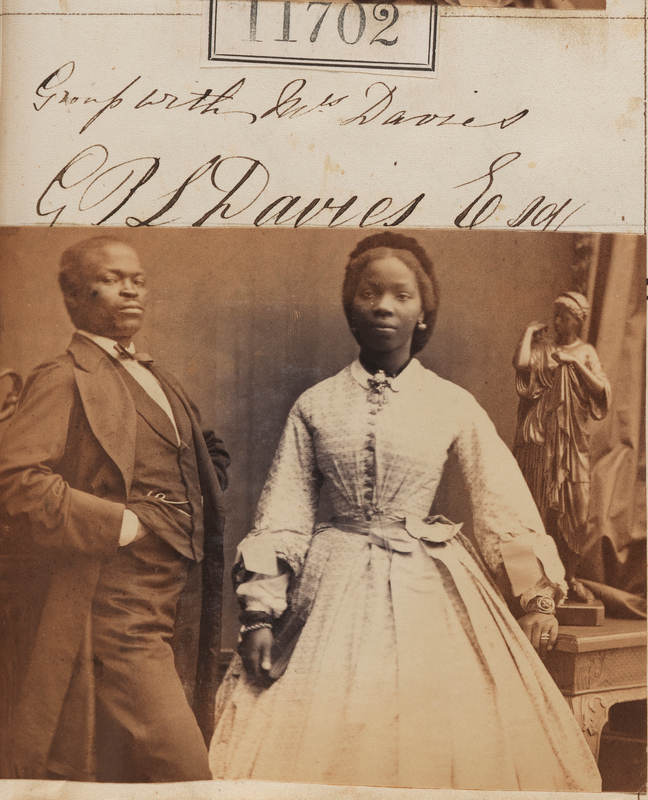

Historically, artworks such as Peter Lely's c.1651 portrait of Elizabeth Murray, Lady Tollemache gilded the brutal reality of slavery by presenting black people as well-dressed servants when in reality there was little distinction between enslavement and servitude.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Peter Lely (1618–1680)

National Trust, Ham HouseWhen those who made their money through plantation slavery abroad returned to Britain they brought their house slaves, who were often children, with them. Taken away from their families and familiar surroundings, these children's lives would have been entirely controlled by their owners and employers.

The 100 well-dressed black cut-out figures in Himid's 'Naming the Money' series of 2004 represent the oft-unnamed black slaves and servants whom we see in paintings like Lely's.

© the artist and Hollybush Gardens. Image credit: Andy Keate

The Dancing Master (from the series 'Naming the Money')

2004, acrylic on wood by Lubaina Himid (b.1954)

Himid created a soundtrack to be played alongside the installation, which consists of short texts through which the cut-outs speak. They share their real names, the names given to them by their masters, details of their lives before displacement and of their lives as slaves and servants – the last line of each piece seeks to reconcile these two identities, showing how individuals might have held onto some element of self after enslavement.

These poetic statements are printed onto a blank balance sheet, undermining the rebranding of forced servitude as gainful employment.

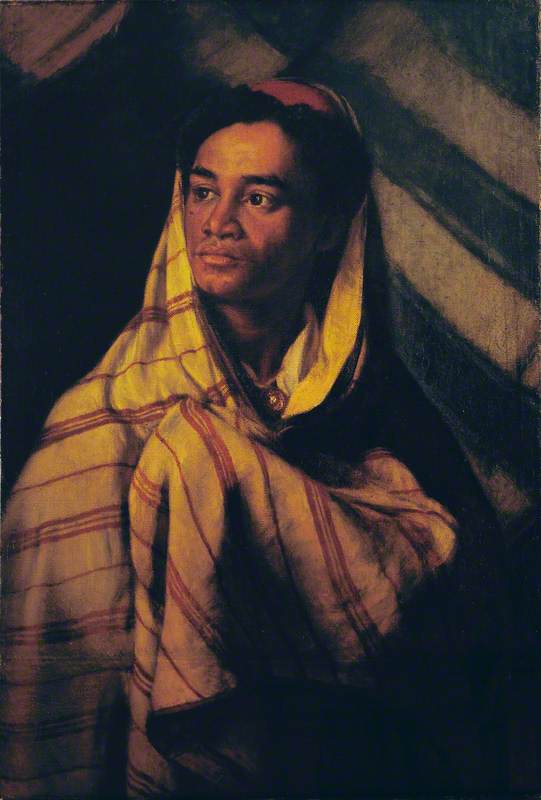

Well-dressed servants are present throughout the Art UK database, in paintings such as John Giles Eccardt's portrait of Lady Grace Carteret from around 1740. These costumes serve the purpose of communicating the aristocratic subject's wealth and taste.

Image credit: National Trust Images

John Giles Eccardt (1720–1779)

National Trust, Ham HouseThe black figures who wear them act as objects of comparison. Their dark skin is contrasted with the lady's paleness and their status is equal to the objects of wealth they hold, whether that be a platter of fruit or flowers or animals like a cockatoo or dog – they serve to set an opulent scene around the elite subjects. The black servant's humanity, individuality and beauty are denied in favour of using them as objects to enhance their mistress' status.

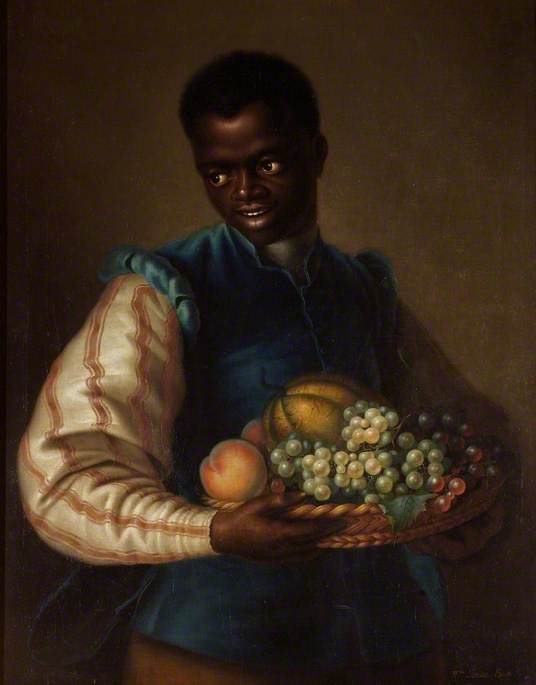

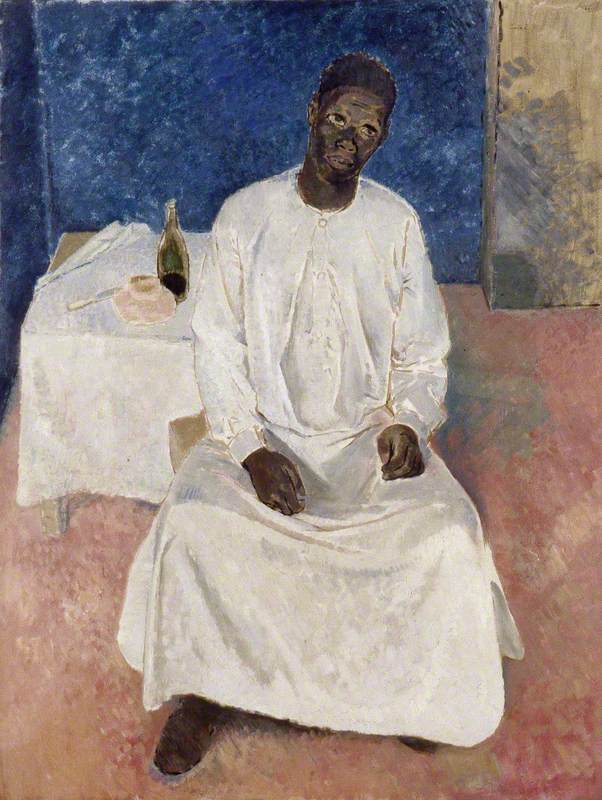

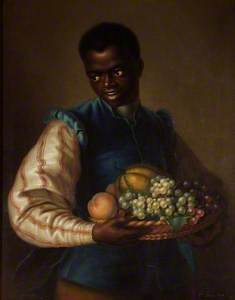

Even when black servants were painted alone, their function as symbols of wealth was still central to the commission. For instance, The Black Boy of c.1769 was painted by still life artist William Jones. That a still life painter was commissioned and not a portrait painter shows that the subject was viewed as an object and not a person, further reiterated by the absence of his name. He becomes just another expensive object recorded for prosperity by his owner. Even without his master in the scene, this young man's servitude is present as he poses serving a tray of fruit.

'A Woman's Place' opens at @KnoleNT today, telling the stories of the women who have contributed to Knole’s spirit and history through the work of six contemporary artists, including the 2017 Turner Prize winner, Lubaina Himid: https://t.co/VRhSFxJqCH pic.twitter.com/vkC7sai4E9

— NT Press Office (@NTPressOffice) May 17, 2018

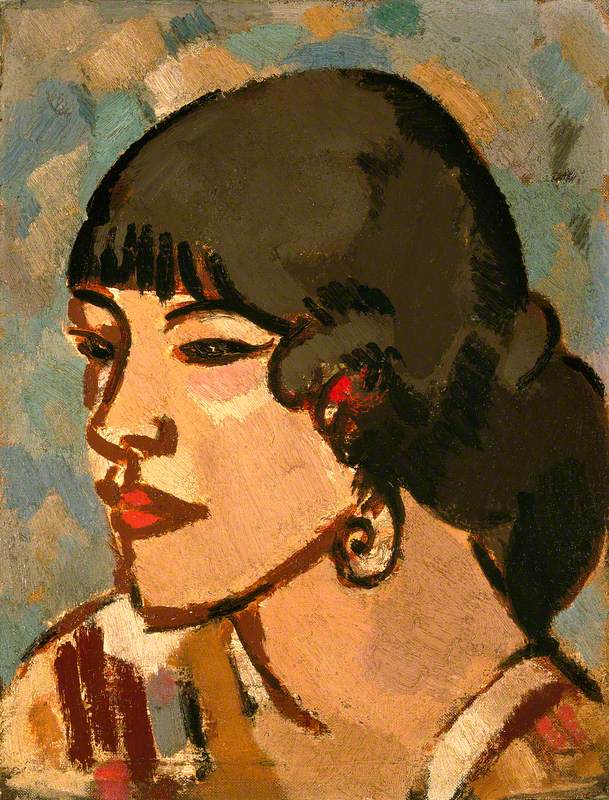

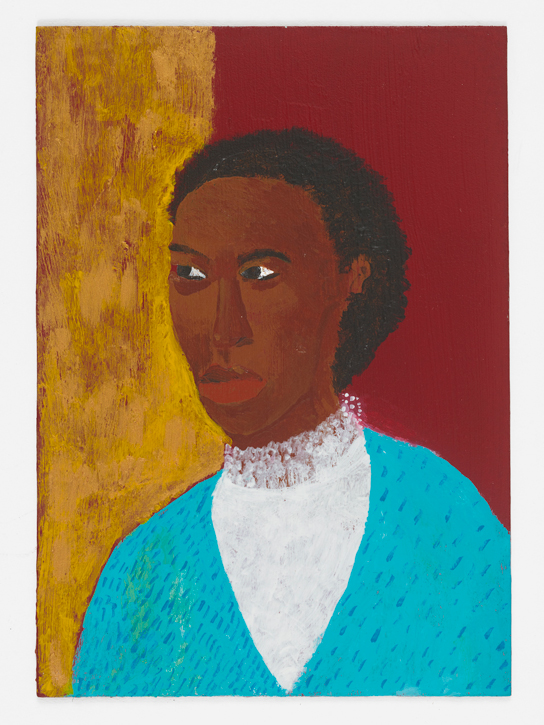

In contrast, Himid's 2018 works Collars and Cuffs and Flag for Grace took the theme of 'A Woman's Place at Knole' and used it to draw attention to the experiences and existence of black servants in British manor houses by taking Grace Robinson, a black laundry maid at Knole, as her subject.

© the artist and Hollybush Gardens. Image credit: Andy Keate

Collars and Cuffs (detail)

2018, acrylic on Zintec by Lubaina Himid (1954)

As the laundress, Robinson would have been an integral part of the function of the house, while also existing very much outside it – the Collars and Cuffs paintings were fixed to drainpipes outside the house to reference this and Robinson's connection to water. Flowing throughout the house, Robinson becomes a ghostly presence. Flag for Grace reclaims Knole for those who worked and cared for it. These interventions make the contributions of black servants like Robinson central to the existence of homes like Knole.

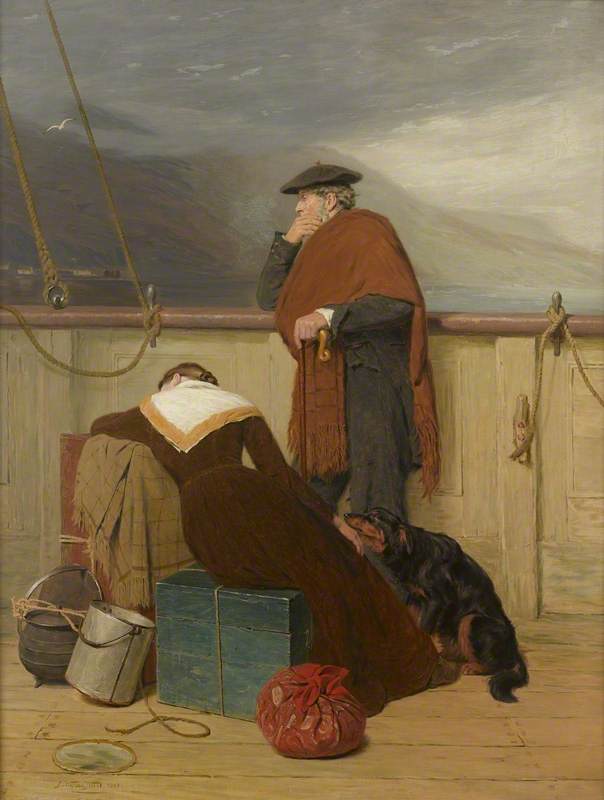

Servants like Robinson continue to feature in paintings throughout the eighteenth century such as Johann Zoffany's The Family of Sir William Young of c.1767–1769 and John Hoppner's George IV (1762–1830), when Prince of Wales of 1780. While in both images servants are seen at work, neither reflects the gruelling reality of the work of domestic servants nor do they acknowledge the work of enslaved people on distant plantations which in the case of Sir William Young, provided the foundation of his wealth.

Image credit: The Mansion House and Guildhall

George IV (1762–1830), when Prince of Wales (after Joshua Reynolds) 1780

John Hoppner (1758–1810)

The Mansion House and GuildhallLike Young, Mary Helden – whose black page is given the racist epithet of 'Sambo' in Charles Philips' Mary Helden (1726–1766) with a Dog and Her Black Page, 'Sambo' of 1739 – benefited from the slave trade as the daughter of John Helden, owner of Negros Nest/Heldens on the island of St Kitts and the wife of Thomas Foster, MP of Egham who owned multiple estates in St Elizabeth, Jamaica.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Mary Helden (1726–1766) with a Dog and Her Black Page, 'Sambo' 1739

Charles Philips (1708–1747)

National Trust, SpriversThe racist label of 'Sambo' characterised black people as lazy overgrown infants who happily served their white masters whom they were directionless without. With its roots in the Spanish word 'Zambo', meaning people of mixed African and Native American descent, this baseless stereotype dates back at least to the colonisation of America and became key to the justification of slavery. Given the source of Helden's wealth, the use of the 'Sambo' caricature is both unsurprising and strategic.

All of these oil paintings play to the 'Sambo' myth by presenting black servants as happy and affectionate towards their masters and mistresses. We see this in Richard Jeffreys Lewis' The Death of Edward Colston of c.1844, which depicts the slave trader Colston at the end of his life.

Image credit: Bristol Museums, Galleries & Archives

The Death of Edward Colston c.1844

Richard Jeffreys Lewis (1822/1823–1883)

Bristol Museums, Galleries & ArchivesThe objects and people around Colston characterise him as a wealthy, well-educated and morally good gentleman and the reaction of Colston's black maid, who seems deeply affected by his death, solidifies this characterisation.

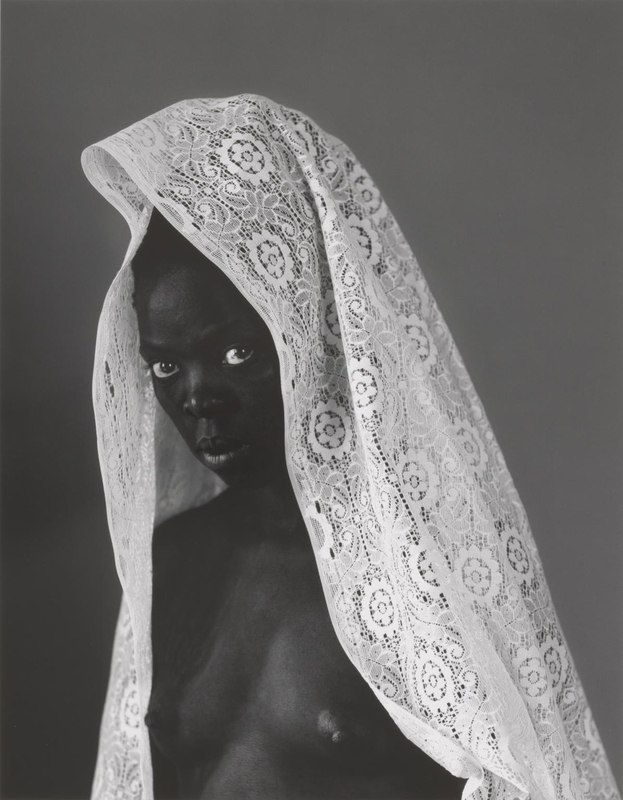

This kind of depiction, of course, erases the terrible mistreatment of black women throughout the slave trade. Not only were they forced into servitude, but they were also forced to bear children who would be born the property of their masters and were often victims of sexual violence.

None of this cruelty is apparent in Lewis' painting. Like the recently toppled statue, this piece was created more than a hundred years after Colston's death and a decade after the abolition of the slave trade across the British Empire. It is clear that men like Colston, who made his money through the Royal African Company as a slave trader, were still celebrated.

Image credit: Paul Francis / Art UK

Edward Colston (1636–1721) 1895

John Cassidy (1860–1939) and Coalbrookdale Foundry (active 1709–2017)

The Centre, BristolThis is unsurprising as similar exploitation was happening across the British Empire during the nineteenth century. As a crucial precursor to it, reframing the slave trade and Colston as benevolent would have added legitimacy to the contemporary actions of the Empire.

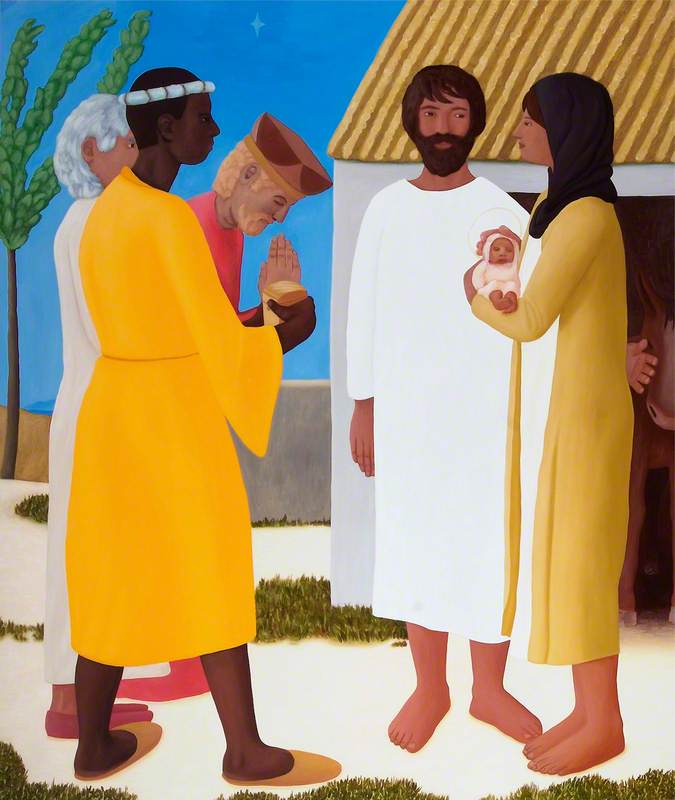

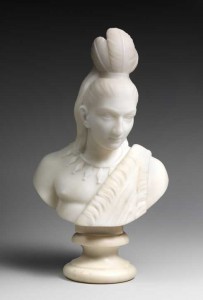

Conversely, Himid's series 'Le Rodeur' deals with the traumatic reality of the transatlantic slave trade and its legacies.

On 6th April 1829, on the illegal French slave ship Le Rodeur, 36 enslaved West Africans had weights tied to their legs and were thrown overboard. Economically, they had become worth more dead than alive because an outbreak of ophthalmia on the ship had left them permanently blind. This was not an isolated event: another example from art history is J. M. W. Turner's The Slave Ship, 1840, which represents the Zong Massacre of 1781, where more than 130 enslaved Africans were murdered by being thrown overboard.

Himid's dreamlike series of paintings allude to the loss of these individuals and the ripples through the ages which occur from this brutal history, attempting to portray that which is impossible to imagine.

This series is so different from the older oil paintings discussed. Rather than a product to proclaim the subject's wealth, Himid produces deeply ambiguous images, which encourages the viewer to find their own meanings – and while doing so, consider the history of Le Rodeur, the enslaved people it carried and the wider history of exploitation which continues to ripple into the present.

To me, the two figures in Le Rodeur: The Pulley seem disconnected: it is unclear if they exist in the same plane or are occupying different times. This makes me consider how the legacies of the slave trade continue to affect the descendants of enslaved people, whether through transgenerational trauma – a much-debated psychological concept which argues that trauma can be transferred from one generation to the next – or through contemporary circumstances which stem from the era of the transatlantic slave trade.

© the artist and Hollybush Gardens. Image credit: Andy Keate

Le Rodeur: The Exchange

2016, acrylic on canvas by Lubaina Himid (b.1954)

Paintings like those in the 'Le Rodeur' series occasionally occupy the same galleries as the traditional oil paintings discussed. Collars and Cuffs and Flag for Grace mark the physical space of the black servant while in some iterations of 'Naming the Money' the figures are in direct dialogue with museum collections. The legacy of the transatlantic slave trade is embedded in our most luxurious spaces and Himid's art activates these spaces to bring the voices of forgotten black subjects to life.

Chloe Austin, curator, art historian and art writer

Further reading

Laura Green, 'Negative Racial Stereotypes and Their Effect on Attitudes Toward African-Americans', published online by the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University, Michigan

Ella S. Mills, 'Lubaina Himid: Naming the Un-Named' in History Today, 4th December 2017

UCL's Legacies of British Slave-ownership

Zoe Whitley, 'Lubaina Himid: 'Telling stories of the black experience that are both everyday and extraordinary is what I'm here to do'', Art Basel 2018