In 1842, The National Gallery acquired Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait for 600 guineas, signed by the artist, dated 1434, and in excellent condition.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

Portrait of Giovanni(?) Arnolfini and his Wife 1434

Jan van Eyck (c.1390–1441)

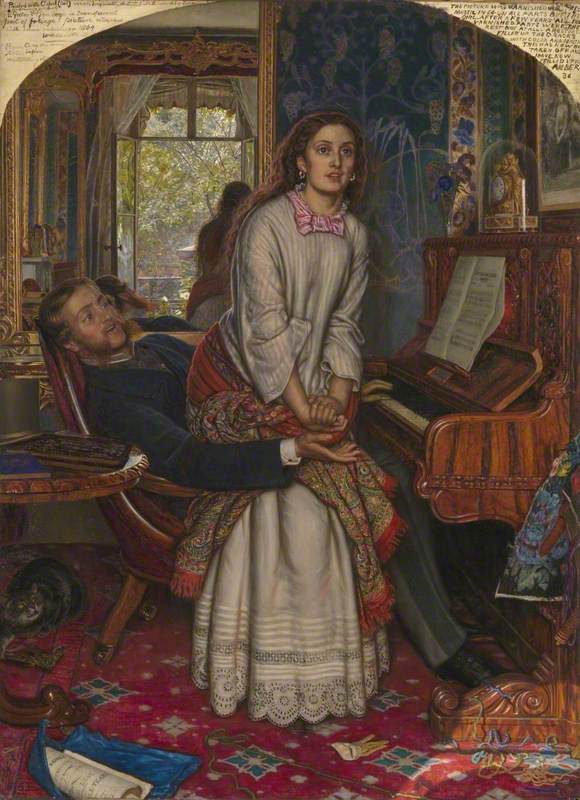

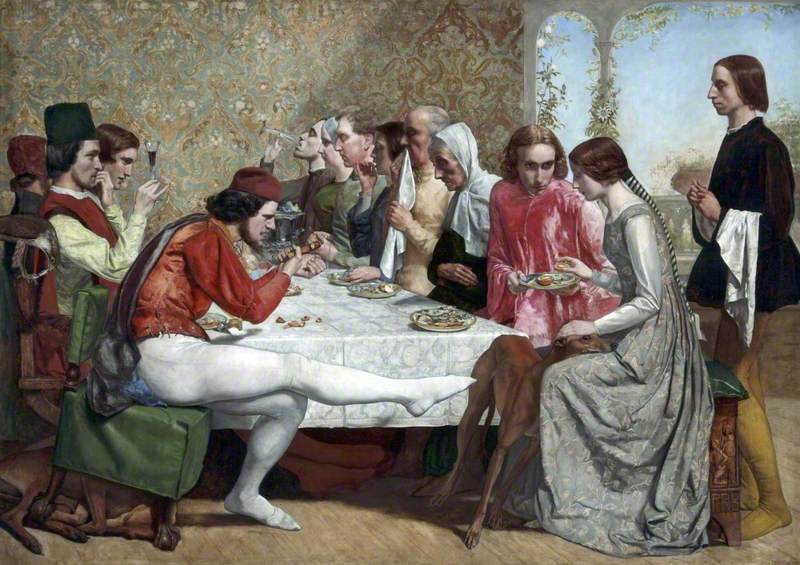

The National Gallery, LondonThe only early Netherlandish painting in the collection, it was completely different in style and subject matter from the traditionally admired works of the great Old Masters. In its meticulous oil painting technique, brilliant colour and extraordinary rendering of reflected light, it inspired a new generation of artists and their successors. The exhibition Reflections: Jan van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites, organised in collaboration with Tate Britain, shows how the painting’s influence resonated right through the second half of the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth century.

It was, above all, the convex mirror in Van Eyck’s painting which introduced the Pre-Raphaelites to new ways of representing real and illusory space.

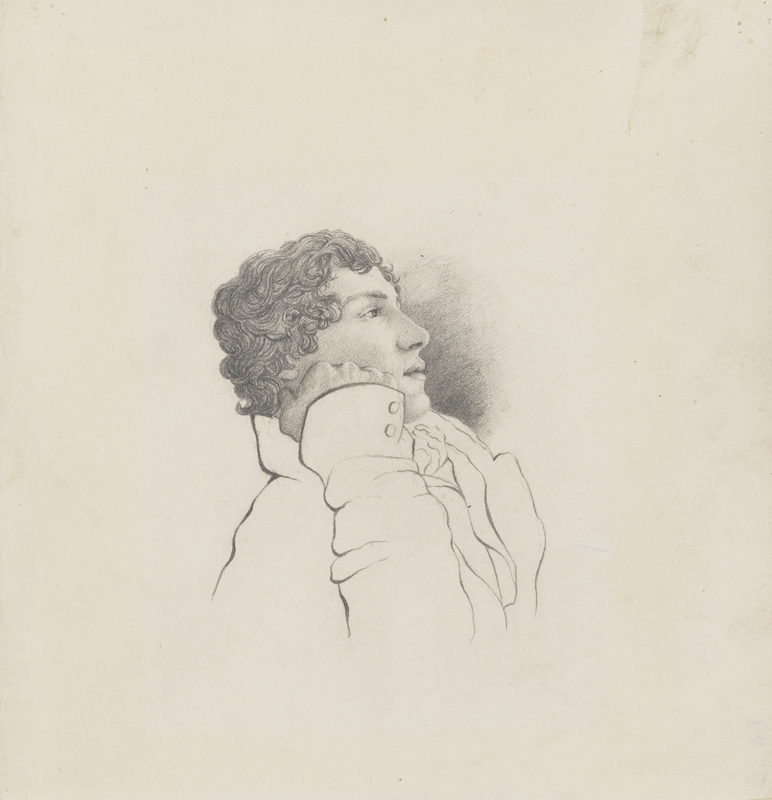

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was formed in 1848 under the leadership of the painters Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt. These young artists had met as students at the Royal Academy Schools, then housed in the National Gallery. Disenchanted with their teaching, and seeking a purer, more authentic form of expression, they looked to medieval art, naming their movement the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. While the Pre-Raphaelites professed admiration for pre-industrial medieval society, they also had a distinctly modern agenda. They abandoned pompous subjects in favour of profound and emotionally resonant themes. Their first works were religious, but they also depicted themes from literature (Shakespeare and Tennyson were favourites) and contemporary life.

A highly compelling painted illusion setting two figures within a richly furnished medieval interior, the Arnolfini Portrait informed the Pre-Raphaelites’ belief in first-hand observation, their use of ordinary objects for symbolic purposes, their detailed technique and bright colours. In the centre of the painting – today believed to represent the Italian merchant Giovanni Arnolfini and his wife – are its two most striking features: Van Eyck’s signature, in the manner of graffiti, and the convex mirror. Surrounded by small glazed scenes of Christ’s Passion, it shows two figures entering the room, apparently to be greeted by Arnolfini. One may be the artist himself.

It was, above all, the convex mirror in Van Eyck’s painting which introduced the Pre-Raphaelites to new ways of representing real and illusory space. It showed them how a mirror, by doubling up the interior space through its reflection, could make a view into a domestic setting more intriguing and mysterious. Artists sought to capture the distorting effects of convex mirrors in their work, for different ends: while Hunt and Brown used mirrors to reflect and intensify the real world, Rossetti and Burne-Jones used them to explore strange aspects of the legendary subjects that interested them at the time. As Pre-Raphaelitism moved into its second phase, artists began to use mirrors to explore their own personal responses to a subject, rather than for symbolic or narrative purposes, hazy reflections capturing a shadowy, ephemeral beauty. By the early twentieth century, artists such as William Nicholson and Mark Gertler no longer aspired to imitate Van Eyck’s technique but continued to be beguiled by the motif of the convex mirror in which the reflection of the artist himself could be discerned.

Susan Foister, Deputy Director, The National Gallery

'Reflections: Jan van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites' was on at The National Gallery in 2018.