Theodore Garman (1924–1954) moved within rarefied artistic circles in Chelsea in the mid-twentieth century. A popular figure among his friends and peers, he was brother-in-law to Lucian Freud and his work was admired for its vibrancy and bold use of colour. Garman's first solo exhibition at the Redfern Gallery in 1950 drew comparisons with Vincent van Gogh, and the artist Matthew Smith wrote the foreword to the catalogue. However, his work was almost completely forgotten until recently.

Despite destroying many canvases when he was dissatisfied with them, a good amount of Garman's work survives in public collections – primarily at The New Art Gallery Walsall. In the last 20 or so years, Garman's work has slowly gained some of the attention and appreciation that it deserves. That said, his work is no secret to gallery audiences in the Black Country; he has consistently been among the most popular artists in the Garman Ryan Collection since its donation in the early 1970s.

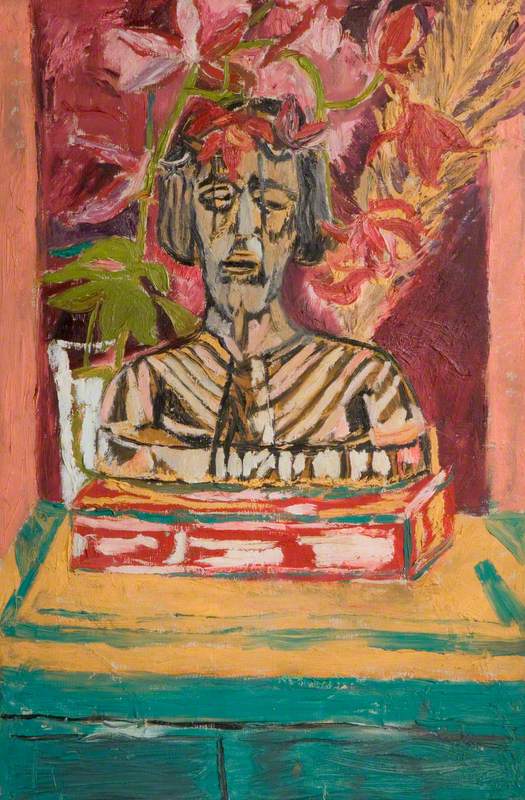

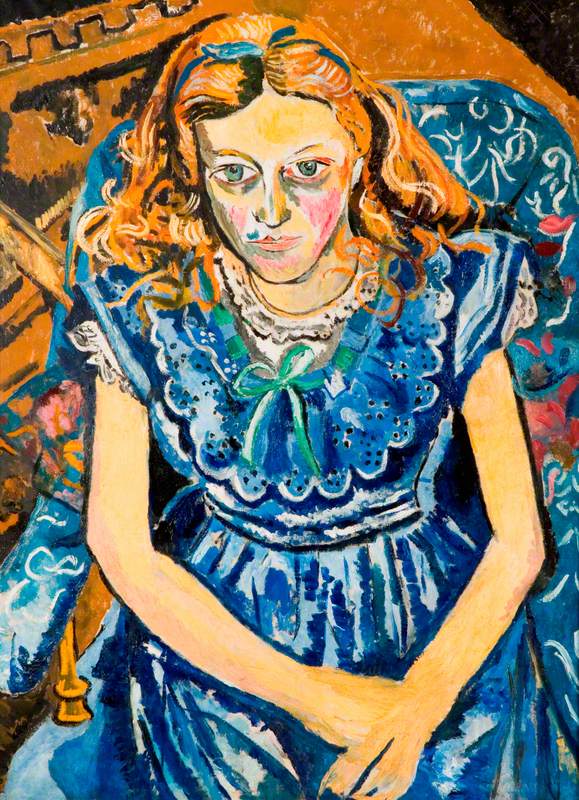

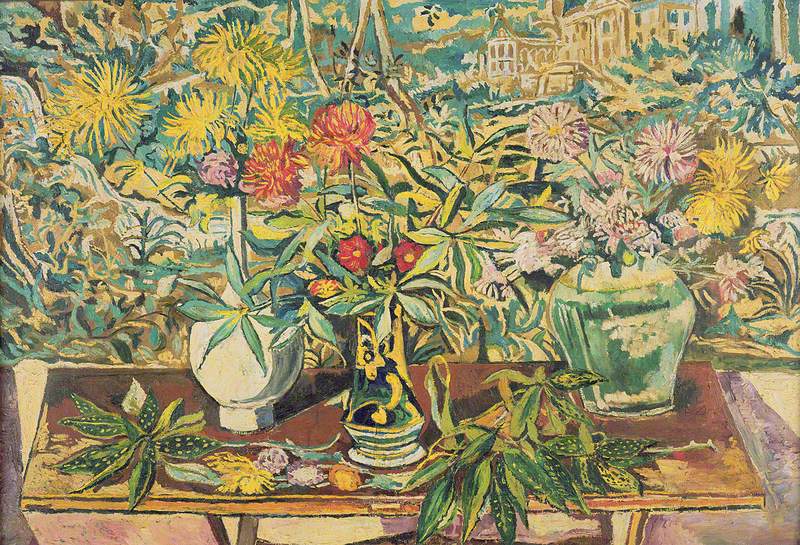

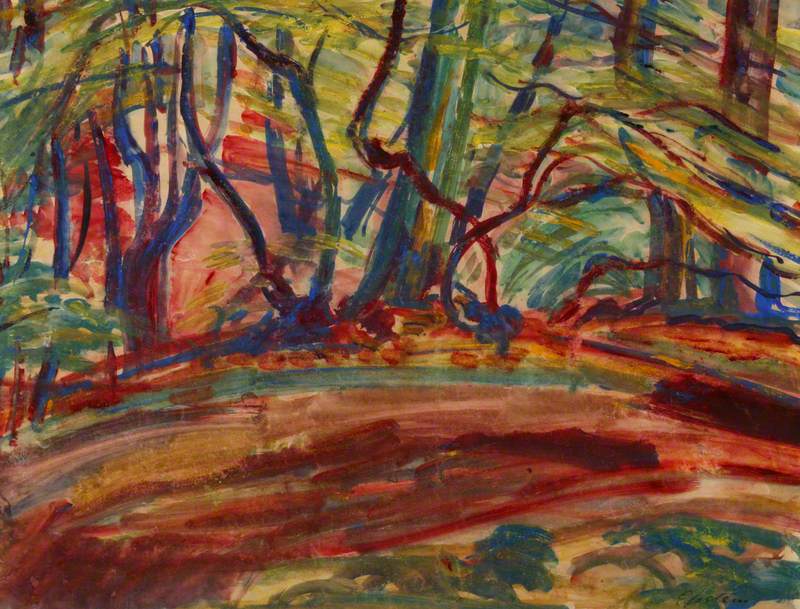

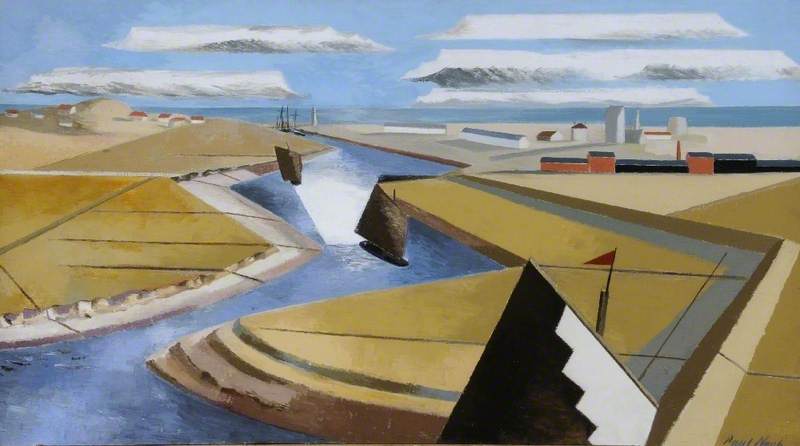

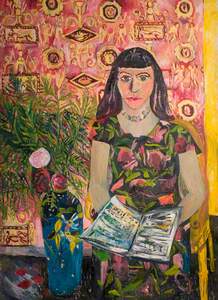

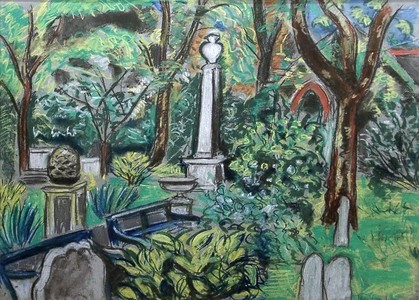

Garman worked across still life, landscape and portraiture for the most part and his style is colourful and rich. The colour and energy in his canvases make Garman's work unmistakably his. Landscapes, garden scenes and flowers do not so much bloom as erupt. This is perfectly illustrated by the 1948 work Autumn Chrysanthemums from the New College, University of Oxford collection; the scene is groaning with nature, positively laden with it.

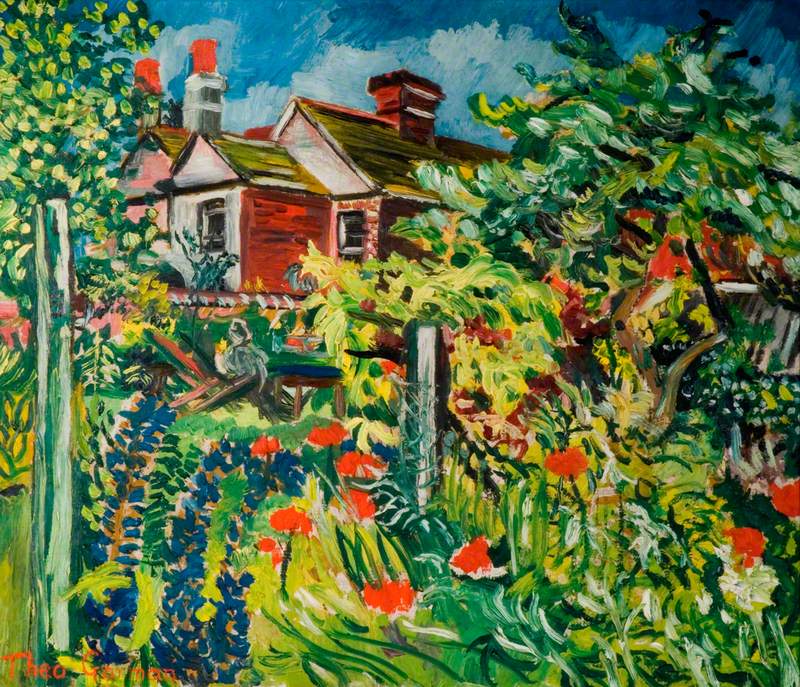

Similarly, in Summer Garden, Harting from the previous year, the house at the centre of the picture – his grandmother's – looks in danger of being completely consumed by the garden.

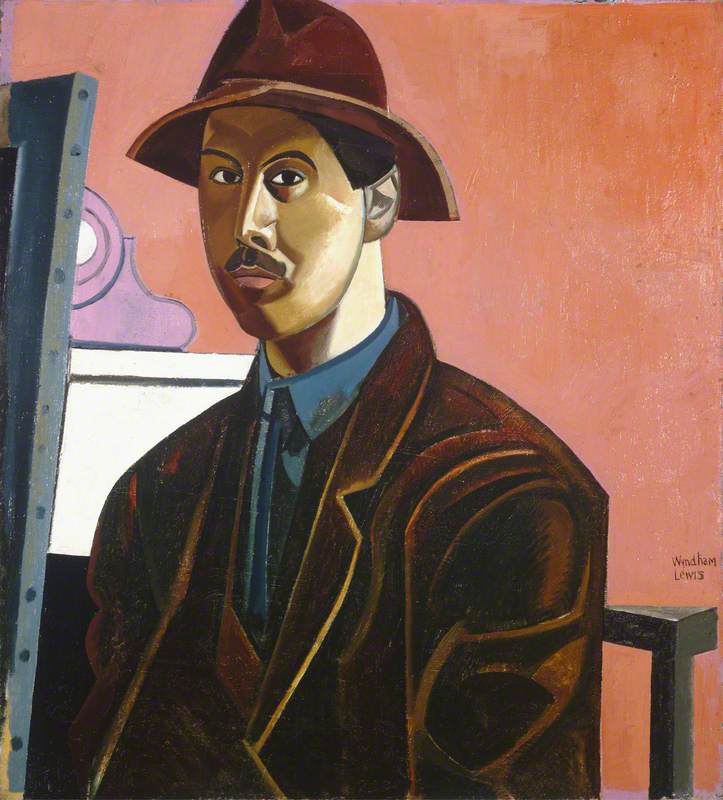

In a review of Garman's debut 1950 exhibition, the artist and critic Wyndham Lewis said his work was 'overwhelmed by a rancid vegetation, tropically gigantic… A little concentration on individual pictures will soon reveal how excellent is the workmanship.' Rancid is right and I don't take this wholly to be a criticism; there is often a feeling of the sickly-sweet end of summer in Garman's paintings.

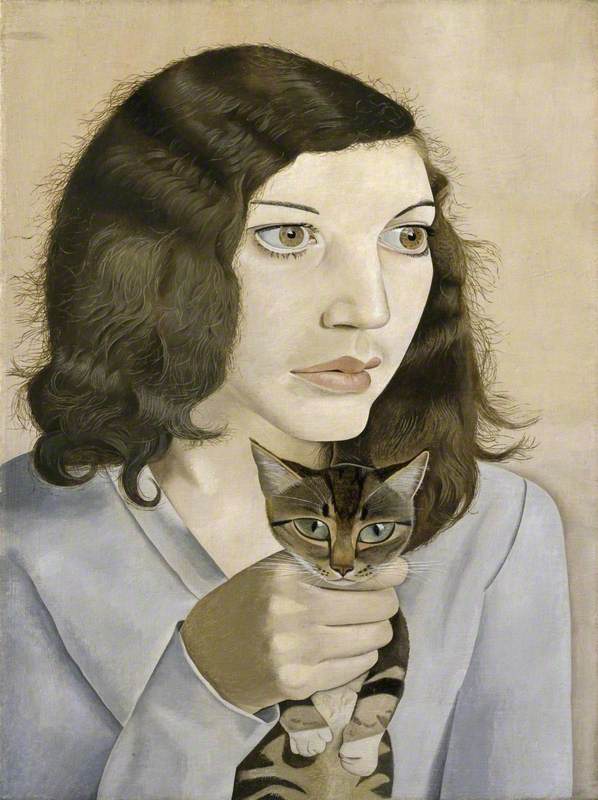

Garman was largely self-taught, but that is not to say he was a complete outsider in the art world nor acutely aware of the history of painting and what was going on in London at the time; a period of seismic changes after the Second World War. He need only look to his brother-in-law Lucian to see that. Garman was dismissive of Modernism, yet his later work showed some flashes of it. He was obsessed with Christian iconography, literature and French painter Eugène Delacroix, referencing him often in the annotations made to the books in his library.

This sense of Garman as an 'Inside Outsider' is important; he is an artist for which separating life and work is difficult and trying would neglect the undoubted connection between the two. It is important, however, not to slip into the myth of the 'troubled artist'. Garman's life was blighted by mental illness at a time when treatments were blunt. His life was also tragically short as a result. Yet this biography is crucial to understanding his work.

Garman, known to friends and family as 'Sonny', was the child of the sculptor Sir Jacob Epstein (1880–1959). Along with his sisters, Kitty and Esther, the children were born to Epstein's model and later second wife Kathleen Garman.

Kathleen is an important figure in the story of cultural heritage in the West Midlands, donating the Garman Ryan Collection to the Borough of Walsall, where she grew up, in 1973. It is here where most of Garman's work in public collections survives.

Epstein's family circumstances were, to say the least, complex. He bore five children by three different women, none of whom were his first wife, the long-suffering Margaret.

Theo, Kitty and Esther were not publicly recognised as Epstein's children as his infidelity, let alone children born outside of marriage, would have caused a scandal in early twentieth-century society. It is worth remembering that in the 1940s and 1950s, Epstein was arguably the most famous artist in Britain. In the face of Victorian sensibilities in wider society, Epstein's reputation was protected at all costs. And those were considerable.

The Garman family lived separately on the Kings Road, with Epstein maintaining his principal family home and studio at Hyde Park Gate. This was primarily to keep his second family a secret, but Kathleen was also fiercely independent. Epstein would visit 272 Kings Road regularly, staying overnight twice a week. His relationship with Theo, Kitty and Esther was, at best, distant. The children likely did not even know Epstein was their father until they were in their 20s.

This is illustrated by a rather cold inscription in one of Garman's books from his library: a gift at Christmas when he was 17, formally signed 'To Sonny from Jacob Epstein'. Years later Garman annotates this simply 'Mio Padre' (My Father).

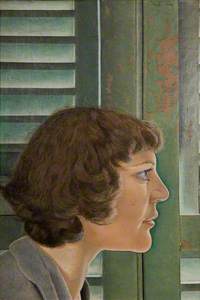

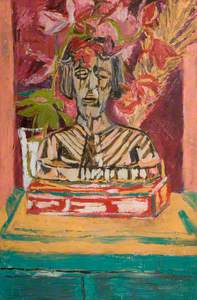

Epstein sculpted his children on numerous occasions – including Kitty and Esther in multiple different sittings. Epstein's First Portrait of Esther (with long hair) is rightly regarded as one of his most important sculptures.

© The estate of Sir Jacob Epstein / Tate Images. Image credit: The New Art Gallery Walsall

First Portrait of Esther (with long hair) 1944

Jacob Epstein (1880–1959)

The New Art Gallery WalsallHowever, Epstein never sculpted Theo; only a couple of sketches of him as a child survive.

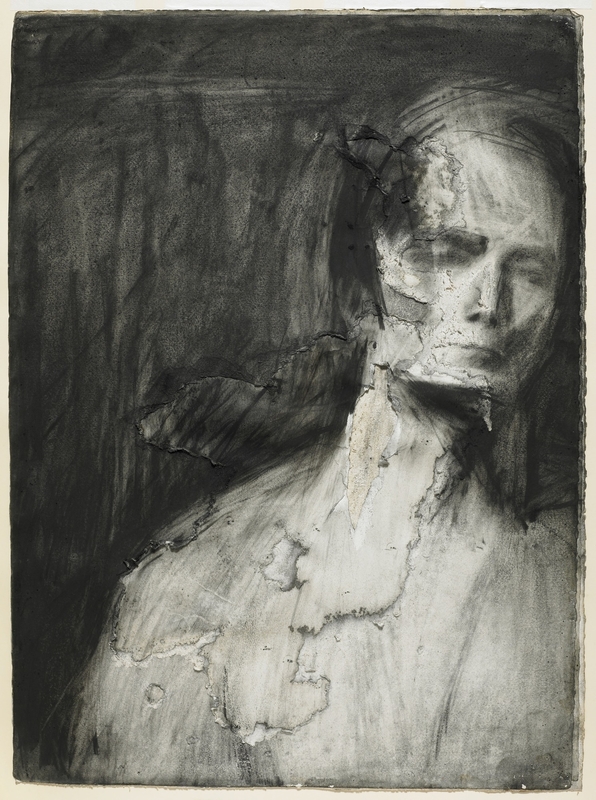

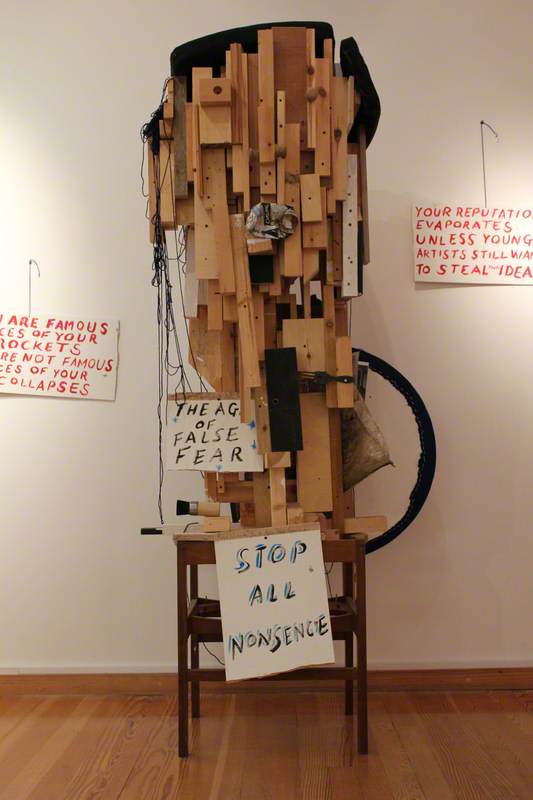

The artist Bob and Roberta Smith referenced Epstein's omission as part of his three-year residency in the Epstein Archive at The New Art Gallery Walsall with Theodore Garman: The Sculpture of His Son that Jacob Epstein Never Made. Smith takes an abstract look at Garman's life, incorporating quotes from his letters to Kathleen and annotations made in his books. The work is large and lumbering, awkwardly constructed and built upwards from an old wooden chair that looks as though it could collapse at any moment.

© the artists. Image credit: The New Art Gallery Walsall

Theodore Garman: The Sculpture of His Son that Jacob Epstein Never Made 2009

Bob and Roberta Smith (b.1963)

The New Art Gallery WalsallEpstein did take an interest in Garman's artistic career, and there was some common ground between the two in this regard. There are certainly similarities in the vibrancy and energy of their styles – clear here in a painting by Epstein of Epping Forest from around 1930.

Both looked to the art of the past for inspiration, Garman with Christian iconography, Epstein with his personal collection of African and Oceanic sculpture. Yet the personal distance between the two was only amplified in official circles; there is a real tragedy in looking back at this from a more progressive present.

In an article from a January edition of The Sphere, Garman's 1950 Redfern Gallery exhibition is featured prominently. Epstein and Garman are pictured side by side at the preview, with Garman referred to only as Epstein's 'brilliant young protége' and never his son.

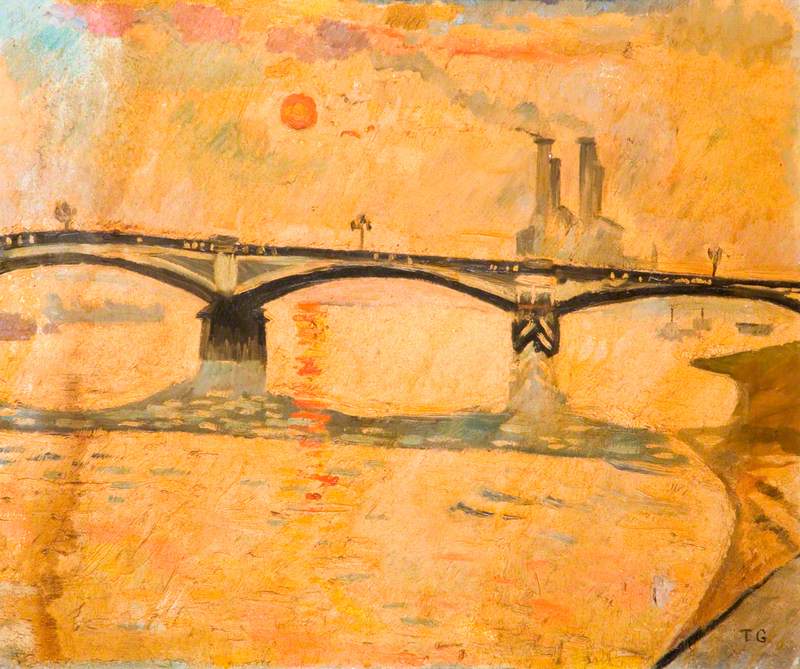

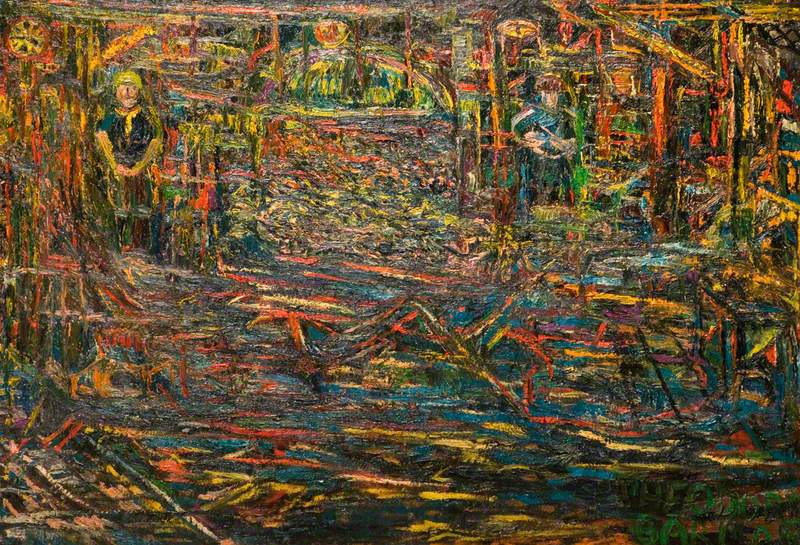

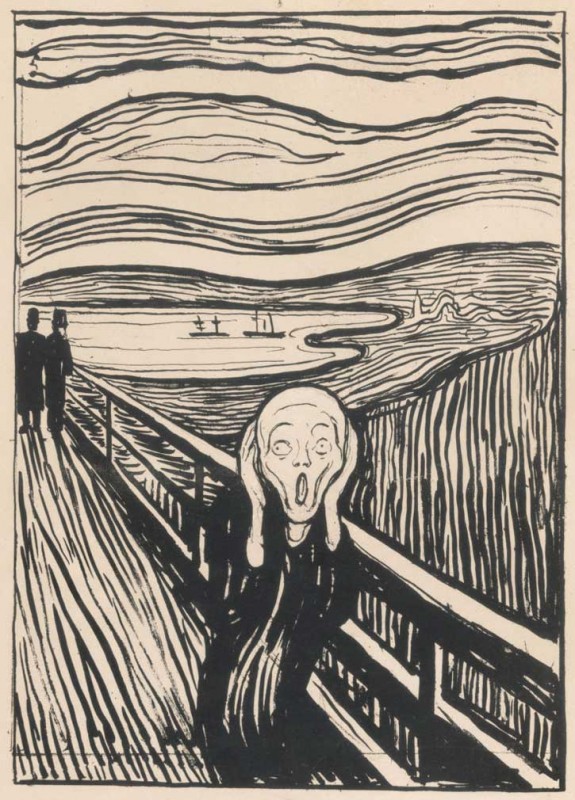

Garman had his first mental health crisis in 1945. He suffered acutely and progressively with what was diagnosed at the time as schizophrenia. Two of his last surviving paintings, The Old Forge, Chelsea (I & II), are very different in character to his brightly coloured, more representational earlier works such as The Thames from Chelsea Embankment (1946).

Dark and brooding, with the thickest of impasto – the paint literally hangs off the canvas – they are extraordinary works that are difficult to read without the context of Garman's worsening mental health. Yet, they are strikingly modern paintings for the early 1950s, and call to mind the careers of later artists such as Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff.

Garman died on 22nd January 1954, aged 29. The circumstances surrounding his death are shrouded in supposition, but it is clear that he died of heart failure following a botched attempt to admit him to a mental health institution. His younger sister, Esther, witnessed the terrible events of that evening and never recovered. Suffering from her own long-standing mental health challenges, Esther took her own life on 5th November of the same year.

© the copyright holder. Image credit: courtesy The New Art Gallery Walsall

Theo Garman with Esther seated on his lap

c.1945, photograph by Ida Kar (1908–1974)

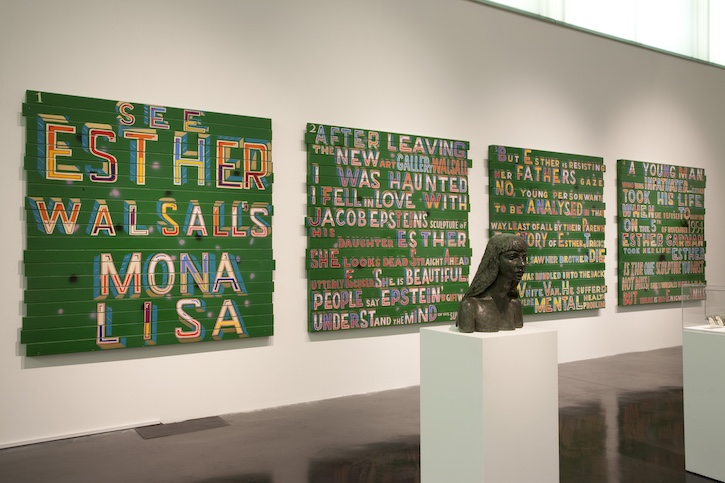

In the residency that Bob and Roberta Smith undertook at The New Art Gallery Walsall between 2009 and 2012, the lives of Theo and Esther were central to that project. Smith made a series of works celebrating their lives and giving their stories a platform.

Image credit: Jonathan Shaw / The New Art Gallery Walsall

Installation view, 'Life of the Mind', The New Art Gallery Walsall, 2011

Bob and Roberta Smith's 'See Esther Walsall’s Mona Lisa' (background)'; Jacob Epstein's 'Esther' (foreground)

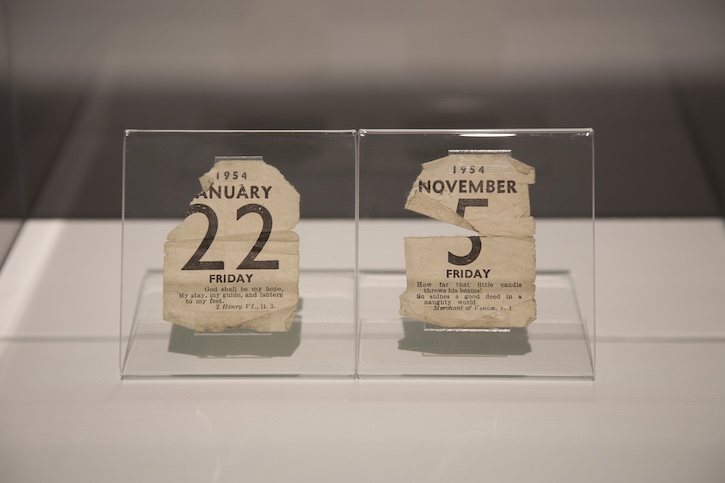

During the project, a single object found in a box of detritus in the Epstein Archive sums up the tragedy that hung over the family better than any. Two calendar dates mark the days that Theo and Esther died and were kept for decades by their mother Kathleen.

Image credit: Jonathan Shaw / The New Art Gallery Walsall

Newspaper cuttings showing the dates Theo and Esther Garman died

From the 'Life of the Mind' exhibition, The New Art Gallery Walsall, 2011

This year, 2024, marks the centenary of Garman's birth. His life was complex, troubled and at the mercy of rigid societal morality and unsophisticated mental health care. There are lessons here around the 'Great Male Artist' – how the wellbeing of Epstein's family was collateral damage to the preservation of his career.

However, what is clear – and largely thanks to the work of The New Art Gallery Walsall – is that Garman's work has received more attention and appreciation on its own terms in the last quarter century than at any time since his death. For an artist that lived and breathed painting, this would surely be appreciated.

Neil Lebeter, curator and writer

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation

Further reading

Cressida Connolly, The Rare and the Beautiful: The Lives of the Garman Sisters, HarperCollins, 2004

Jennifer Gray, '"Ten bob's worth of beauty?" Theodore Garman (1924–54) and his place in mid-20th-century British art', in British Art Journal, vol. 9, no. 1, spring 2008

Neil Lebeter, HOW TO LET AN ARTIST RIFLE THROUGH YOUR ARCHIVE, The New Art Gallery Walsall, 2012