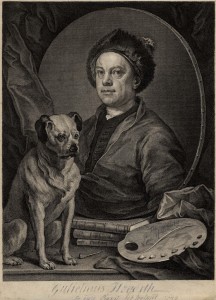

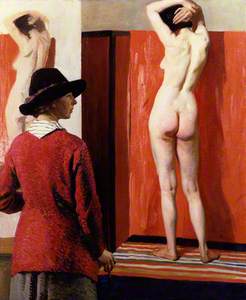

'Men act and women appear', observed art critic John Berger in his landmark 1972 work, Ways of Seeing. What might first seem like a sexist statement against women becomes a cutting observation on the ways in which women are socialised to be in the world.

'From earlier childhood', Berger continues, 'she has been taught and persuaded to survey herself continually... Her own sense of being in herself is supplanted by a sense of being appreciated as herself by another.' In other words, women are often taught from an early age to regard themselves through the lens of the masculine subject.

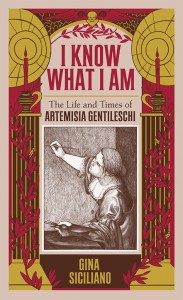

The male gaze has dominated much of our culture, even in art. First, it is important to note that women have historically often been driven out of art. The skills-based and advanced form of traditional art meant that the discipline was seen to be exclusive to upper-class, educated men – the first woman was admitted to the Royal Academy Schools in 1860, almost 100 years after the Academy's establishment in 1768.

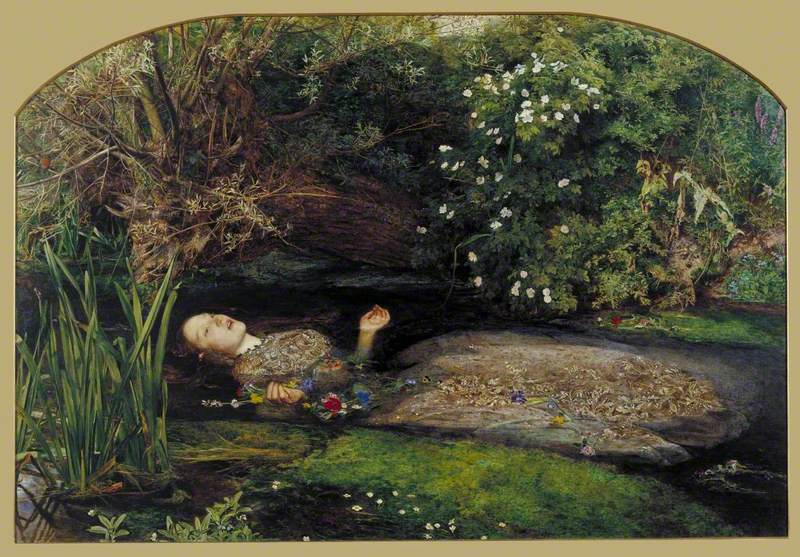

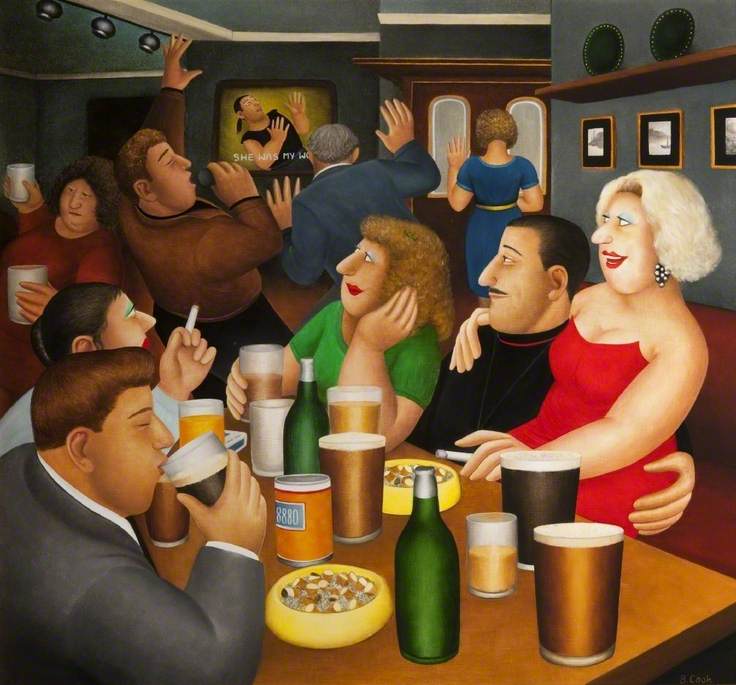

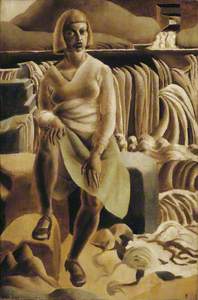

It is perhaps unsurprising, but still disappointing to observe, then, women were often depicted as aesthetically pleasurable objects prone to destructive suffering, or engaged in seduction of the unassuming man (note that a woman could technically be 'active' in this schematic, but only in the service of male pleasure).

And yet history has shown us that the courage of women to defy power knows no bounds. The first female student admitted to the RA, Laura Herford, was in fact admitted on accident after her work was only stamped with the initials, L. H. – later histories would recount this incident as 'the invasion'. The history of British art is similarly full of intriguing women who played about with the male gaze, using their art to comment and subvert the limits of femininity often imposed from above.

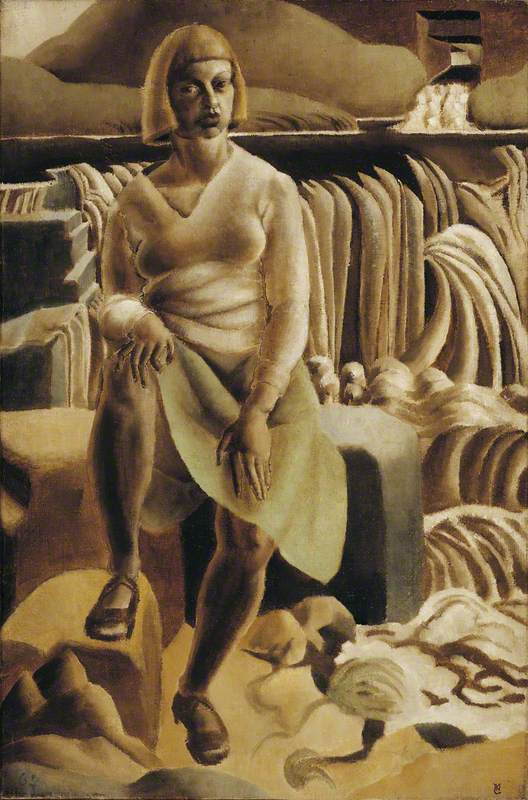

British pop artist Pauline Boty's Colour Her Gone depicts Marilyn Monroe set against a bed of roses, relaxing in a light blue loose shirt and a blissful smile. The tranquil, almost divine nature of the scene – the celebration of Monroe – is almost spiritual in its depiction of the Hollywood star.

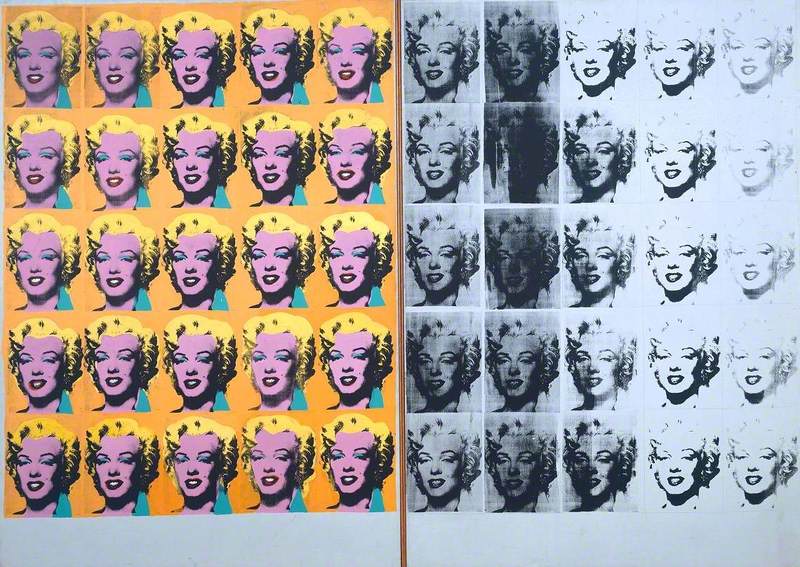

Contrast this with her contemporaries' pop art portraits of Monroe, such as Andy Warhol's Diptych, which sees the late actress through the prism of her meta-image as film star; the gradual gradations of the portrait from full colour to black and white symbolise the recent death of the star at the time.

Both Warhol and Boty's works explore Marilyn Monroe in the context of her recent death. Only Boty's, however, offers us insight into a different side of the actress that goes beyond the superficial image of stardom. We are used to seeing glamorous actresses paraded as cultural icons, their images being used in the service of the entertainment industry. We are less used to seeing the women behind these images as complex beings with active internal lives themselves.

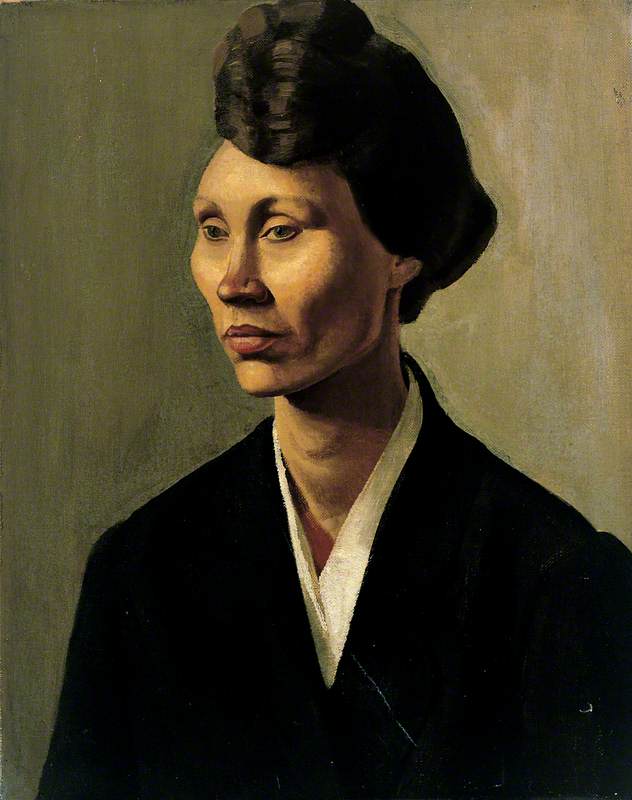

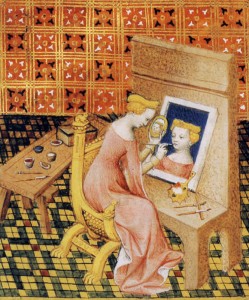

Women artists have often turned to self-portraiture as a way to express their sense of inner life, tackling the idea that women operate in the world merely as objects for male pleasure. Self-portraiture offers an artist the unique ability to present themselves to the world on their own terms.

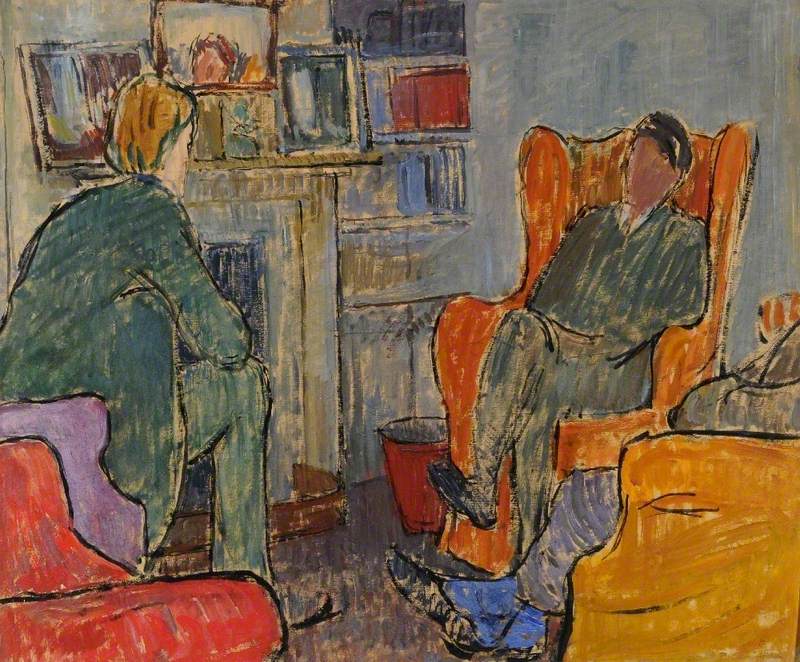

Artists such as Jean Cooke, Julie Held and many others, have made portraits of themselves that depict them as human beings with real depth, in spite of standing on a two-dimensional flat surface.

Reflecting on her portrait, artist Julie Held notes that the painting was intended to capture a specific moment 'at a flower stall outside Oxford Circus... although I was buying the flowers as a gift for someone, I suddenly had a memory of buying flowers for my mother years before she was ill in hospital.' The 'deep sadness' Held felt in the moment is represented by the navy blue background in the portrait, offset by the vibrancy of the sienna yellows at the bottom of the bouquet, which signal the arrival of hope. 'Even under the shadow of an illness or a very bleak period in your life, a flowering clematis can bring you momentary great pleasure and joy.' Held's self-portrait breaks apart the conventions of space and time: her portrait travels through time, with emotions and experiences all contained in its small canvas.

The recent #MeToo movement has presented the rude awakening for some men that they, too, must negotiate their behaviour. Earlier this year, a short story in The New Yorker called 'Cat Person' went viral – almost unheard of for a short story – for its straight-handed depiction of one woman's internal battles, insecurities, and anxieties during a romantic encounter. Again, some were unsettled by the unapologetic presentation of a women's ambiguity. And yet, change does not merely happen by chance: they are the result of many years of individual and collective toil, the summation of many small uprisings and instances of resistance. In our celebration of women such as Pauline Boty, Julie Held, and Jean Cooke, we should take them as not only icons of the past, but also figureheads to work for a better future.

Rebecca Liu, writer