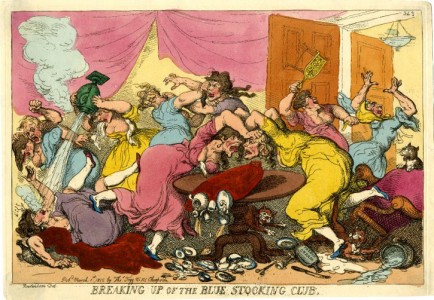

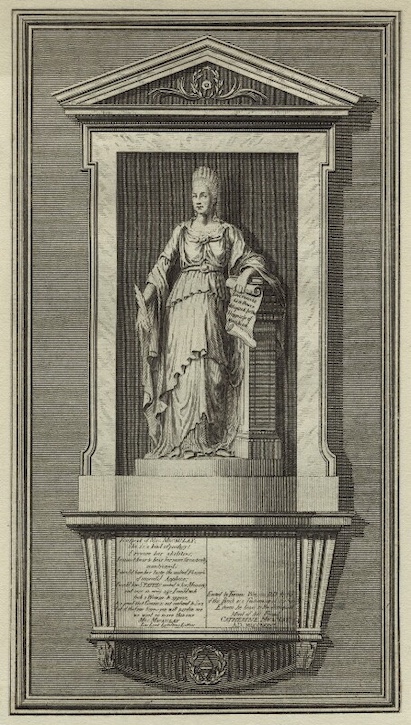

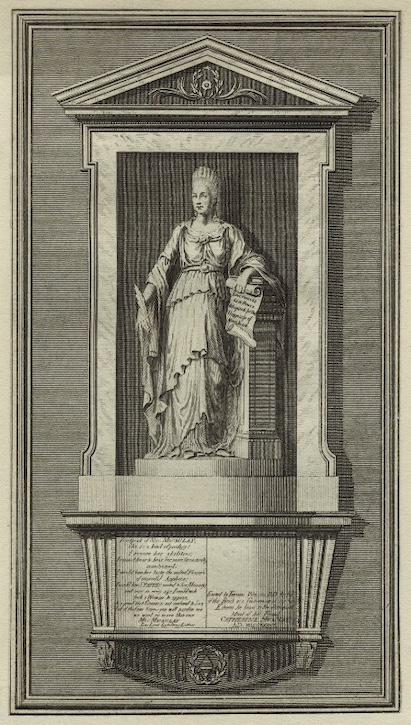

In November 1777, a new monumental sculpture was unveiled near the altar of the London church of St Stephen Walbrook. A personification of History, the white marble statue by John Francis Moore (c.1745–1809) was in a classicising vein, the elegant, drapery-clad figure recalling a Roman matron or deity.

Image credit: Warrington Museum & Art Gallery

Catharine Macaulay (1731–1791), Historian, as History 1778

John Francis Moore (c.1745–1809)

Warrington Museum & Art GalleryWhile, to the modern eye, there may appear nothing outwardly untoward about the monument, it was in fact deeply controversial, the church wardens quickly insisting on its removal. That the imagery was overtly secular and pagan in origin was upsetting enough. But still more troubling perhaps was the notoriety and politics of its dedicatee, the historian Catharine Macaulay (1731–1791).

Image credit: Warrington Museum & Art Gallery

Catharine Macaulay (1731–1791), Historian, as History 1778

John Francis Moore (c.1745–1809)

Warrington Museum & Art GalleryMoore's statue was an idealised portrait of Macaulay as Clio, the Muse of History, who is often shown holding an open scroll or book – clearly seen in this print. Similarly, Macaulay is depicted holding a quill pen in her right hand and a scroll in her other.

Image credit: The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Clio, the Muse of History reading a book

1763, etching on paper by William Wynne Ryland (1733–1783), after Guercino (1591–1666)

Moreover, she leans on the first five volumes of her monumental History of England from the Accession of James I to the Revolution. Eventually running to eight volumes, published between 1763 and 1783, this radical political history of the seventeenth century was widely admired. Lauded as 'the female Thucydides' by the writer Horace Walpole (1717–1797), Macaulay quickly rose to high public prominence on the back of the book's success.

But, as the fate of the monument to her in St Stephen's illustrates, Macaulay's fame as England's first published female historian was not uncontentious. While the first volumes of her History were lauded as a valuable counter to David Hume's (1711–1776) recent Tory History of England (1754–1761), and received warmly by those of a progressive Whig outlook, Macaulay's later enthusiasm for the Commonwealth era and more radical advocacy of republicanism alienated many of her former supporters, Walpole among them.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Catharine Macaulay, née Sawbridge c.1775

Robert Edge Pine (1730–1788)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonBorn Catharine Sawbridge in 1731, she was the daughter of a wealthy city family based in Kent. Like many women of her social standing, she received little formal education, later claiming that she owed what learning she had acquired to her prodigious reading of classical texts found in her father's library.

She married the Scottish physician Dr George Macaulay (1716–1766) relatively late, at the age of 30, and had one child, Catharine Sophia. He was supportive of her studies, the first volume of the History of England appearing not long into their marriage. Its enthusiastic reception ensured Macaulay's fame even before her husband's untimely death in 1766.

Macaulay's intellectual achievements and gifts saw her aligned with the first generation of Bluestockings, a coterie of accomplished, high-born women who refused to allow their sex to exclude them from intellectual pursuits. The group included the author and salon hostess Elizabeth Montagu (1718–1800) and the painter Angelica Kauffmann (1741–1807). Distinguished in their own lifetimes, these women's learning was represented as a sign of national progress in ways that consolidated rather than challenged conventional ideals of femininity, as moral and sociable, modest and refined.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Portraits in the Characters of the Muses in the Temple of Apollo 1778

Richard Samuel (d.1787)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonRichard Samuel's highly idealised 1778 painting equating the women with the nine Muses depicts an assembly of creative women being presented as members of a modern pantheon of arts and letters. Macaulay sits below Apollo, unfurling the scroll of History for the attention of the so-called 'Queen of the Blues' Montagu and her fellow Muses. While the image presents these women as a collective group, there were in fact as many differences as commonalities. As a fierce Tory, Montagu, for instance, would have disagreed fervently with Macaulay's political sympathies.

Macaulay's History had been immediately recognised as different from any study that had preceded it, in terms of both the rigour of scholarship and its explicit republicanism. Beginning with the accession of James I (who reigned in England from 1603 to 1625), it related the history of the English Civil Wars as primarily a struggle against the absolutist tendencies of the Stuarts to win back rights first ceded under the 'Norman yoke'.

While the first volumes of Macaulay's account were warmly welcomed by those of Whiggish sympathies such as Walpole, her later justification of the execution of Charles I and enthusiasm for the Commonwealth alienated many of her earlier supporters. Her vocal criticism of government policy in the lead-up to the American War of Independence (1775–1783), and advocacy of the principles on which the American Congress was founded, only served to stoke further controversy.

Always keenly aware of her cultural visibility, Macaulay and her admirers supported the production of a rich array of formal portraits, prints, figurines and sculptures that promoted the overlaps between her politics and work as a historian. Throughout the 1760s and 1770s, Macaulay sat for portraits almost annually. These saw the author assume or be cast in a variety of guises: a Roman senator, the great matriarch Cornelia, the personification of Liberty, and most controversially, as History itself.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Catharine Macaulay (née Sawbridge)

1765, line engraving by James Basire (1730–1802), after Giovanni Battista Cipriani (1727–1785)

Engraved by Giovanni Battista Cipriani (1727–1785), after a design by one of Macaulay's most ardent supporters, the author Thomas Hollis (1720–1774), what would become the frontispiece to the History of England portrays its author as Libertas. Based on a Roman coin designed by Marcus Brutus, issued shortly after the assignation of Julius Caesar, it played on Macaulay's association with liberty and the repudiation of tyranny. That she appears garlanded with oak leaves aligned her patriotically with those Britons who also fought for these values, the Commonwealth heroes lionised in her History.

In the mid-1760s, Macaulay sat for the fashionable portrait painter Catherine Read (1723–1778), who portrayed her in silky, vaguely classical drapery, seated amongst the letters and published books that made her name. Along with the stories of having immersed herself in the authors of antiquity found on her father's bookshelves, depicting Macaulay in classical guise indicated her authority as a historian and political commentator informed by the most severe ideals of Roman republicanism.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Catharine Macaulay (née Sawbridge)

1764, mezzotint by Jonathan Spilsbury (c.1737–1812), after Catherine Read (1823–1778)

Made shortly after her husband's death, in a lost miniature, known now only through a print, Read also compared Macaulay with the widow of the Roman Republican consul Tiberius and mother of the Gracchi, Cornelia, a figure famed for her writing as well as devotion to her sons' political careers. This image of Macaulay grieving over an urn was appropriate given that she was recently widowed. But it made a political point too: as the legend at the bottom of the work informs us, she laments 'lost Liberties'.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Catharine Macaulay in the character of a Roman matron lamenting the lost liberties of Rome

1770, line engraving by William (active 1770), after Catherine Read (1723–1778)

Published in the wake of the so-called 'Boston Massacre' of early 1770, in which British soldiers fired on a group of local citizens, killing five, the image keyed into growing tensions between the colonies and the English government's suppression of 'fellow' English subjects' liberties.

Here, Macaulay was being likened to the ideal Roman matron, a figure who combined the virtues of private, feminine feeling with public service. But later portraits of Macaulay downplayed displays of sentiment, electing instead (as the dispute with the American colonies sank into open warfare) to assert her political sympathies.

Painting around 1775, Robert Edge Pine (1730–1788) promoted Macaulay's commitment to representative government. While once again portrayed as a Roman matron, she also wears the distinctive purple sash of an elected Roman Senator.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Catharine Macaulay, née Sawbridge c.1775

Robert Edge Pine (1730–1788)

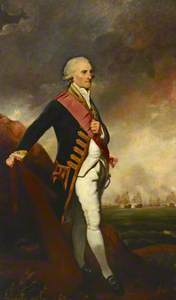

National Portrait Gallery, LondonIn the portraiture of Pine's contemporaries, notably that of Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), women of elevated rank were commonly represented 'as' or in the character of a classical or literary heroine, while men were depicted in terms of what they did.

Image credit: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Admiral Lord George Brydges Rodney (1719–1792), 1st Baron Rodney

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

Royal Museums GreenwichBlurring these conventions, it is uncertain whether Pine presents the viewer with Macaulay as History or as a historian. She holds a quill and leans on volumes of her History. But these can just as easily be seen as the tools and outcome of her trade as much as the attributes of a personification.

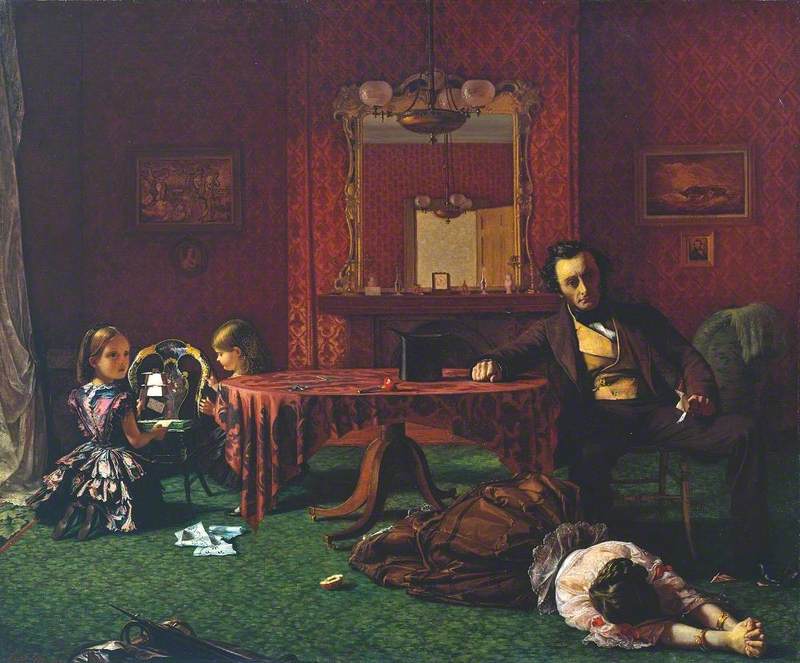

In her left hand, Pine shows Macaulay holding a letter addressed to Dr Thomas Wilson. A doting admirer of the historian, who probably commissioned the portrait, Wilson had opened up his house and library to Macaulay and her daughter on their moving to Bath for the good of the writer's health in 1774. This relationship was commemorated in a striking but unusual portrait by Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797), featuring Wilson in the role of adoptive father to Macaulay's daughter, the presence of the otherwise absent historian in their lives symbolised by the open book between the two sitters.

Image credit: Chawton House

The Reverend Thomas Wilson (1703–1784) and Miss Catherine Macaulay (1731–1791)

Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797)

Chawton HouseIt was Wilson who also paid for and oversaw the installation in late 1777 of the larger-than-life statue of Macaulay in St Stephen Walbrook, using his position as rector.

There are hints in the St Stephen statue as to what made Macaulay such a troubling figure for some. The symbolism is conventional enough, the owl brooch she wears being an emblem of Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom but also war. Yet it is perhaps not the details still present that are most intriguing so much as those now missing. The statue was originally mounted on a plinth which, as with the pedestal in Pine's portrait, was inscribed with a line from the History of England: 'GOVERNMENT/ Is a power/ delegated for the/ HAPPINESS of/ MANKIND,/ when conducted by/ WISDOM, JUSTICE/ and MERCY.'

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Catharine Macaulay as History

1777 or after, line engraving by John Francis Moore (d.1809) (after)

Besides the outrage of erecting a monument free of religious symbolism and dedicated to a person still living in a sacred space, it also therefore made an overtly public political statement at a time of heightened division and unrest over the conflict in America. Indeed, it celebrated a figure openly associated with the promotion of representative government and opposed to monarchical tyranny, issues at the very heart of the 'civil war' now being waged across the Atlantic.

Writers in the press attacked Wilson vociferously, an article in The Lady's Magazine accusing him of 'prostituting the church'. Yet Wilson pointedly refused to remove the statue, only agreeing when, a year or so after its installation, Macaulay unexpectedly eloped with a far younger man, William Graham. Indeed, the marriage lost Macaulay many of her supporters. She continued to write, publishing the last three volumes of her History of England over the next five years, but Macaulay never fully escaped the scandal of her second marriage, being subject to scurrilous rumours and vicious attacks on her gender and sexuality.

Image credit: The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Figure of Catherine Macaulay in character of History

1773, soft-paste porcelain by Chelsea-Derby Porcelain Factory (1770–1784), after J. F. Moore (active 1773)

The fluctuations in Macaulay's reputation are revealing of the mixed and shifting attitudes to female authorship and learning in the later eighteenth century. While feted for much of the 1760s and 1770s, along with other accomplished female artists and writers, as exemplary of the progress of polite culture and society in Britain, by the time of Macaulay's death in 1791 perceptions of women's intellectual achievements had altered drastically, being viewed with suspicion, not admiration. Macaulay was vilified more than some perhaps, in part because she was less conservative than other 'brilliant women' of her day in her attitudes to class and sexuality, but also because of her extraordinary political articulacy and the public visibility she had at times cultivated in paint, print and stone.

John Bonehill, lecturer in History of Art at the University of Glasgow

This content was supported by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation