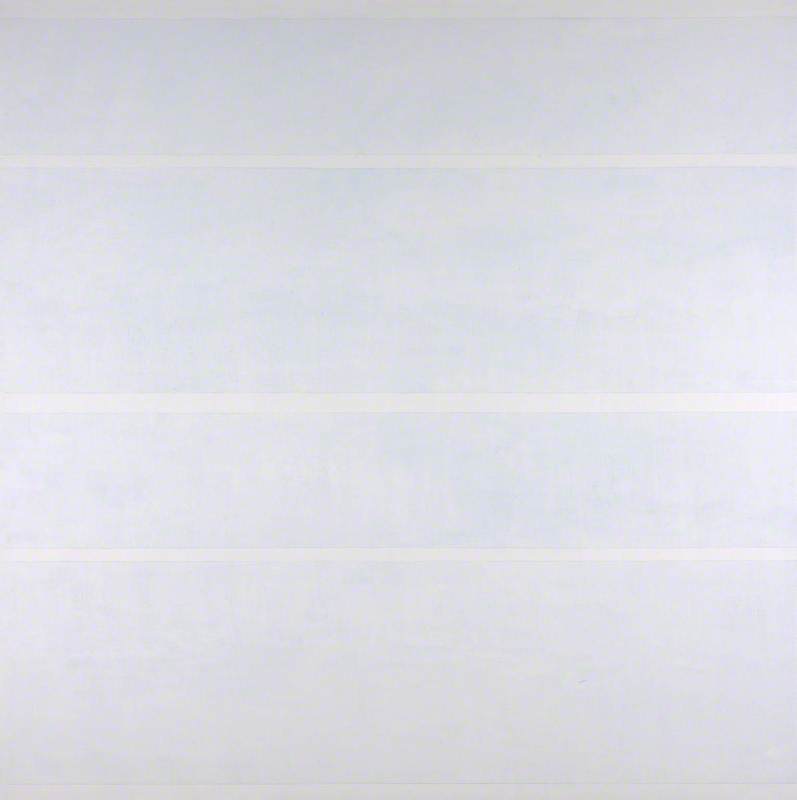

Rana Begum is an alchemist when it comes to colour and light.

Rana Begum

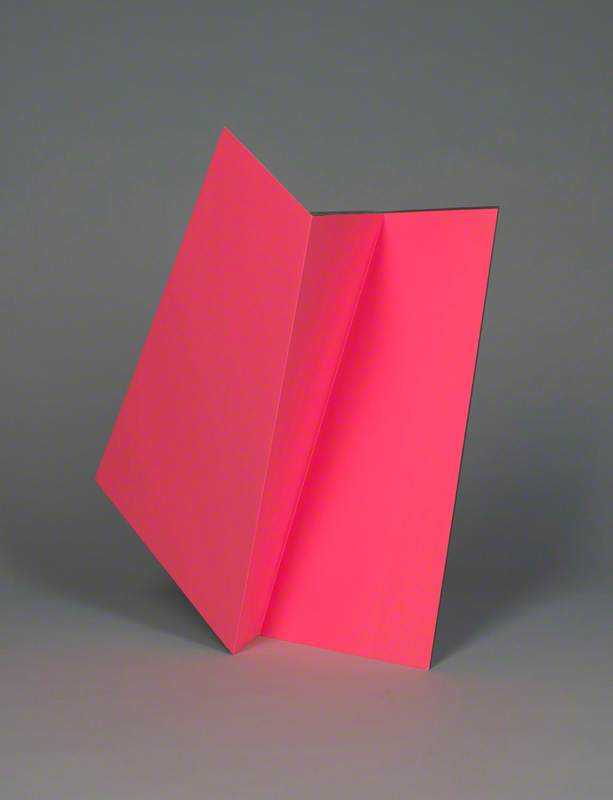

She experiments with the refraction and reflection of beams of light and tests how they impact our experience of colour. She refines her findings to make site-specific installations, sculptures and paintings, which harness these relationships and effects. As a result, a work like No. 429 SFold (2013) is a sophisticated illusion. The metal geometry changes with our movement, creating shifting shapes and a warping palette where colours blur and hover beyond the artwork.

In this vein, Begum takes from the language of Minimalism and Constructivism and refreshes it with influences from Islamic design and urban landscapes. With an architectural sensitivity, she finds inspiration in the city environment, often using Instagram as a sketchbook to capture and record details.

Ahead of her solo show with Kate Macgarry, recently rescheduled to spring 2021, we spoke about her practice, the importance of collaboration and building her confidence with colour.

Cleo Roberts: You've often mentioned the impact American Minimalism had during your foundational studies at Hertfordshire University. Do you return to these artists?

Rana Begum: Recently I've been looking at the work of Agnes Martin. I remember reading that she moved from New York to New Mexico and spent time there on her own in total isolation. I struggled with the first three to four weeks of lockdown and had a complete creative block. I was juggling homeschooling, moving my studio, managing my team and working from home. It was a lot! I really found relief and solace from all of that in Martin's paintings and through watching a number of her documentaries. I love her work, she's one of the artists I consistently return to. That helped me to get back to my normal mind-set.

Cleo: You mention your studio move. Can you tell us about where you've settled?

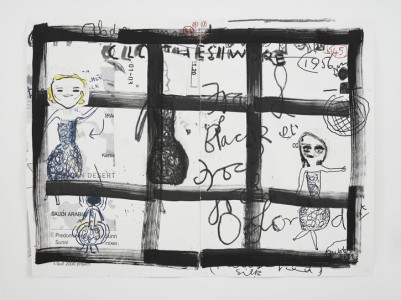

Rana: I'm in a new home and studio. It's been a nine-year project and it's the studio of my dreams! The building used to be an engineering factory that had to be demolished for the build. I bought some of the machines and materials and found sheets of tracing paper, which I love for its delicate and transparent qualities. I've been using these found materials to get back into drawing.

Rana Begum

In the basement is my main workshop with the milling machine and chop saw for both woodwork and metal. On the ground floor, there are two spaces, one for documenting and putting up the work and the other for doing finer, detailed work. I also have some outdoor space and it's designed so that the doors can open up and there's no separation between indoors and outdoors.

Cleo: How has this design been shaped by your practice?

Rana: Natural light is really important to me. The architect Peter Culley (Spatial Affairs Bureau) made sure the studio has skylights. These have been a crucial part of the process of making my work. Since moving in, it has been great to observe the changes in light each day and I often have to just stop everything and pause for several moments just to take it in.

No. 976 Net

2020, mesh installation by Rana Begum (b.1977) at Roksanda's autumn/winter 2020 fashion show

Cleo: You're taking stock but also watching and learning how to play games with light. Can you tell us about the impetus for the large network which spread across the Foreign and Commonwealth Office earlier this year?

Rana: This was a collaboration with fashion designer Roksanda. I was excited and overwhelmed by the space. It was flooded with natural light and I knew it would be amazing to do something which filtered this light. I installed a large work consisting of coloured net cutting in bold lines across the hall. It required a series of anchor points to pin the net to so it could be stretched into a series of vivid shapes.

Rana Begum

Cleo: Given the fabric of the building, that must have taken quite some consideration and input from technical teams. Are you comfortable working with others?

Rana: I love a challenge and being able to collaborate with people. I often work with structural engineers, designers and architects. I really enjoy that part of the process. When you have these conversations, you think of the material and work in ways you might not have otherwise been able to. I enjoy flexibility and try really hard not to restrict how I work and keep it as open as possible.

My practice is such that I work on lots of different series all the time and also a few works at the same time from the same series. I like to be hands-on and make the work from beginning to end as much as possible. When I'm limited with machines then I outsource some of the parts. I make models because I can't draw very well and can't do 3D drawing. Also models are a great way to understand the materials and I can take them outside to see how they react to the light.

Cleo: You've cultivated a practice that sees you frequently switching materials and confidently working with colour. Do you have a comfort zone?

Rana: I don't like to be in a comfort zone. My attention span is very low – I get bored quite easily! I need things that constantly make me ask questions and push the works. Even with my folding works, I need to keep pushing them – I won't make the same one twice.

Out of the three main elements in my work, colour is the one I struggle with. However, through experimentation, my confidence has grown. I love the contrasts and immersive experience you can achieve with the works through playing with the colour and materials. With the bar works, you can see there's a gradient effect on each of the blocks. This isn't sprayed on, it naturally occurs as light causes the solid blocks of colour to blend.

Similarly, the halo effect behind the folded work is again simply a play between light and colour as it reflects on the wall. I have an assortment of colour swatches, which I use and I hold on the wall. I've spent a lot of time playing with these and experimenting with different combinations. Of course, because of this, it's important that when the work leaves the studio it is lit properly.

Cleo Roberts, art historian