In collaboration with Towner Eastbourne, 'Queering the collection' highlights works by LGBTQIA+ artists in the collection, written by Collectively podcast host and artist Renee Vaughan Sutherland.

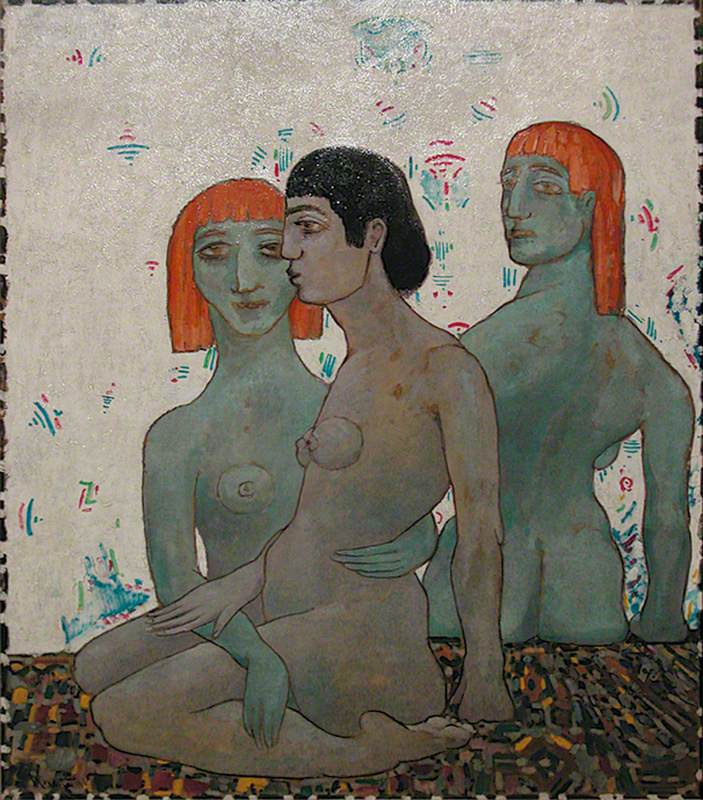

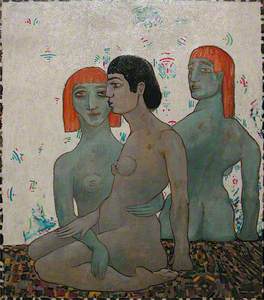

Phelan Gibb's Three Graces found me before I found it. I discovered myself in Towner Eastbourne's art collection storeroom staring at it – transfixed. Every time I revisited it – at least a dozen times – the same spell, increasing in magnitude, settled upon me. It was as if time collapsed and some deep all-knowing intimacy would cocoon me in a close to out-of-body state; I'm looking at myself looking at the picture, I'm watching it be painted, I'm in the image and I pre-date its existence all at once. I never wanted to look away and break the trance-like state it induced.

The Three Graces can feel as though it was created long before its realisation in 1911, but simultaneously it looks radically contemporary. This timeless quality jolted a connection to what a psychic told me a couple of decades ago, that in a past life I was ancient Egyptian royalty. Now, I'm not entirely convinced of reincarnation, but my mind (and no doubt my ego) held steadfast to the notion that somewhere in the space-time continuum I was existing in an antiquated royal culture.

This memory – this feeling of existing both in the past and present – flooded my synapses as the three people within the image who, despite being naked cannot be ascribed within the gender binary, are arranged and outlined in a way that feels similar to the composite pose in Egyptian relief carvings. Behind them on the bedroom wall exists a random arrangement of hieroglyphic symbols: futuristic signs and codes that can't be deciphered yet are intended to be understood. There is a gestural intimacy that binds this potential polycule which leaps off the canvas: it is inclusive and inviting.

Harry Phelan Gibb was born and raised in England but felt deeply connected to his mother's Irish roots. In 1913 he was awarded a solo exhibition in Dublin, but it was shut down by the police shortly after it opened and all his paintings confiscated (they weren't returned to him until 20 years later). Although there is no concrete evidence, we could assume that having been painted in 1911, Three Graces may have been included in that show. The painting's erotic charge, intimate and downright queer ability to astrally project you through the corridor of time would have been a huge threat to The Establishment.

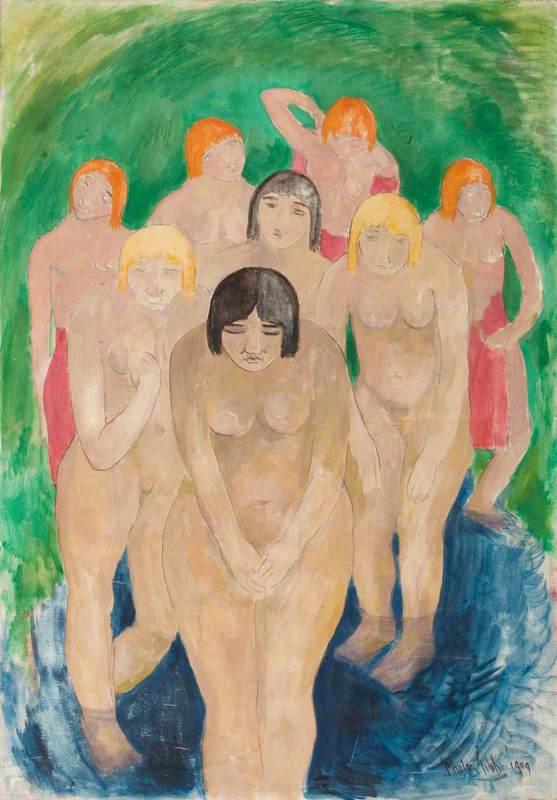

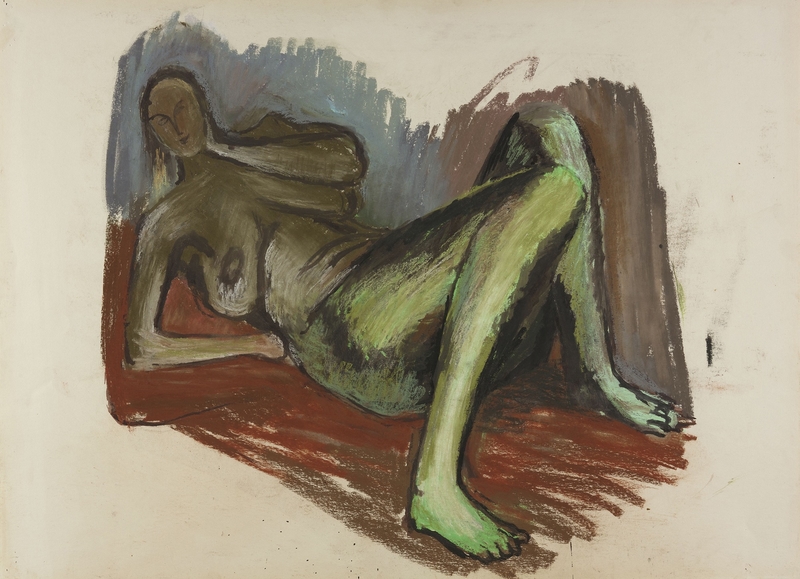

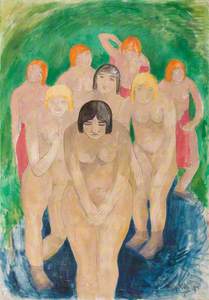

There is little known or written about the impact of this gross injustice but the rejection of Gibb's creativity and imprisonment of his work was no doubt traumatic and to some degree appears to have infected his paintings containing bodies, post-dating this. The strength and confidence of Three Graces literally evaporate and his work becomes timid – bodies are almost always clearly female or young children – soft, blurry forms in positions that communicate apology or shame.

The power of Three Graces, from its point of conception until today, hasn't diminished – far from it. Its sexual charge and inclusive invitation are of the now, but also emphatically communicate queerness existing throughout all time.

Renee Vaughan Sutherland, artist and host of Towner Eastbourne's podcast Collectively