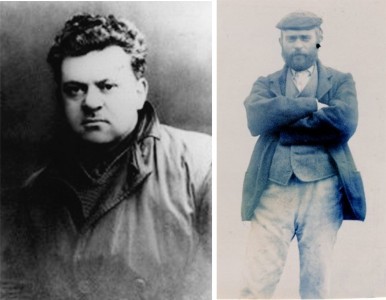

Key figures in the development of Scottish modern art, 'the two Roberts' – Robert Colquhoun (1914–1962) and Robert MacBryde (1913–1966) – were life partners who became inseparable after meeting at the Glasgow School of Art in 1933.

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

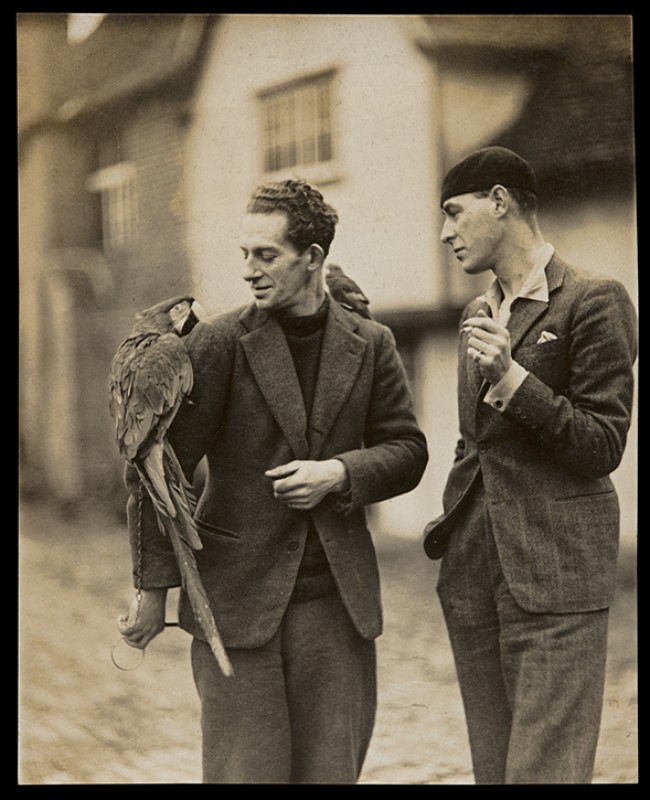

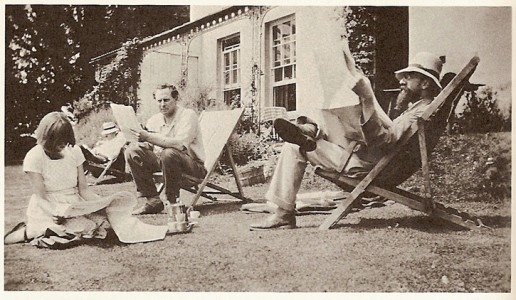

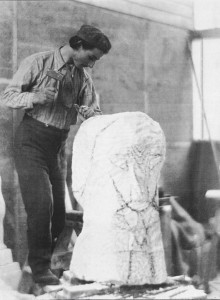

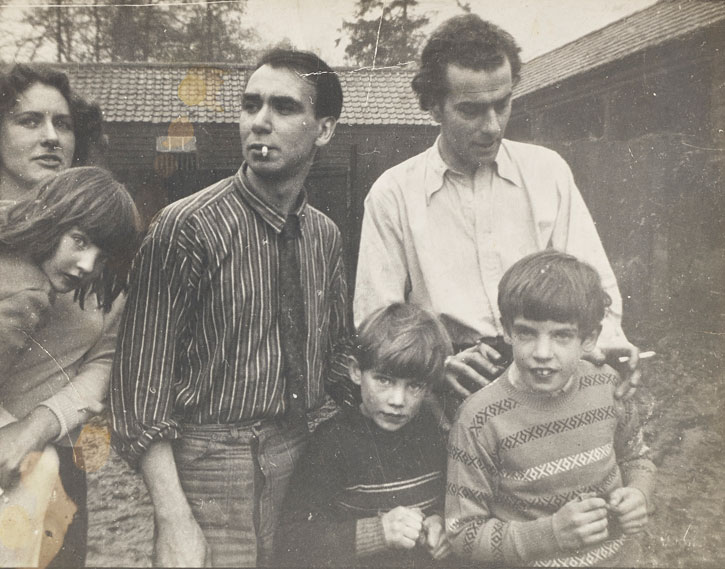

Cedra Osbourne, Robert MacBryde and Robert Colquhoun with the children of Elizabeth Smart

c.1953, photograph by unknown artist, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art Archives, Edinburgh

Although they were never explicit about their relationship with one another, they did not take great pains to hide it, and moments of tender domesticity as well their rougher periods are scattered across the archive. Reflecting on how their lives and works interact sheds some light on queer relationships before the decriminalisation of homosexuality in the late 1960s.

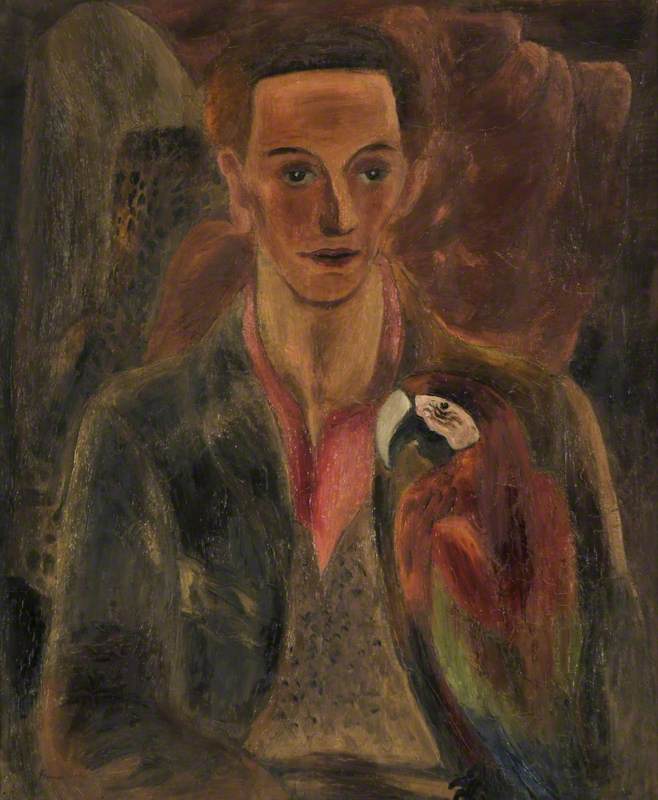

© the artist's estate / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

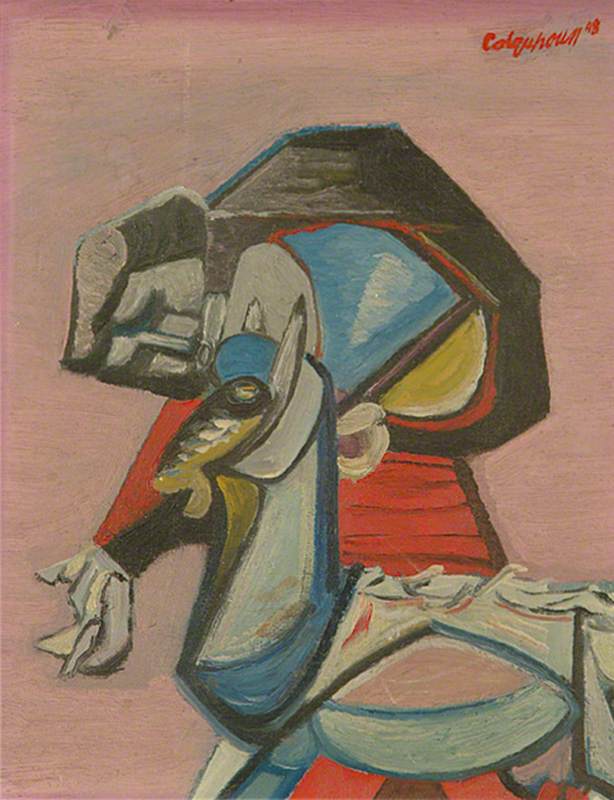

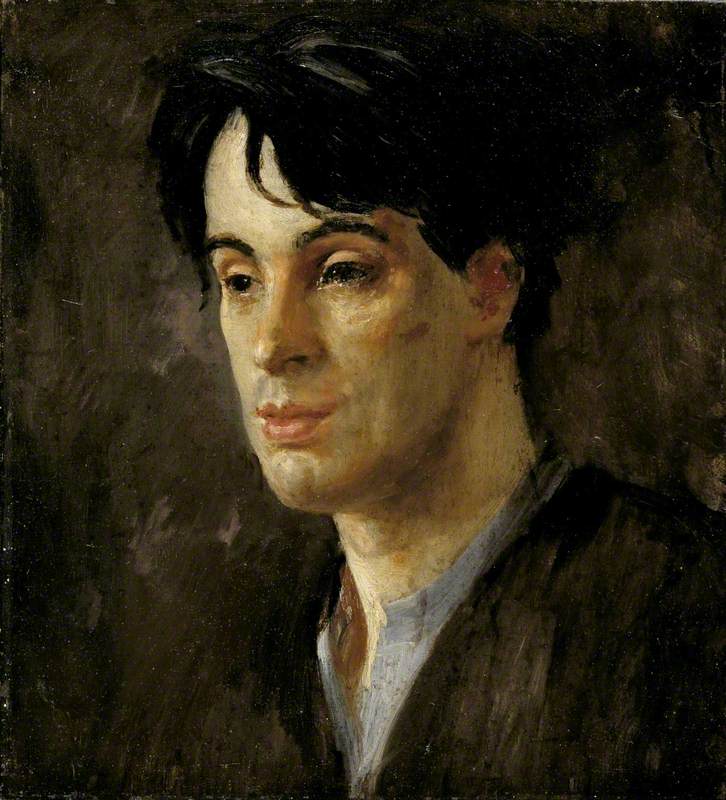

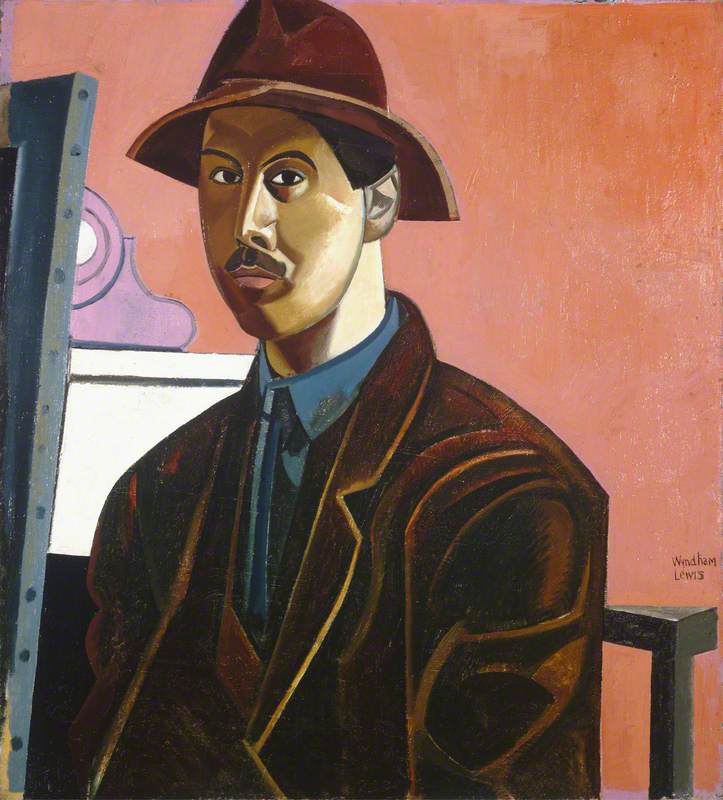

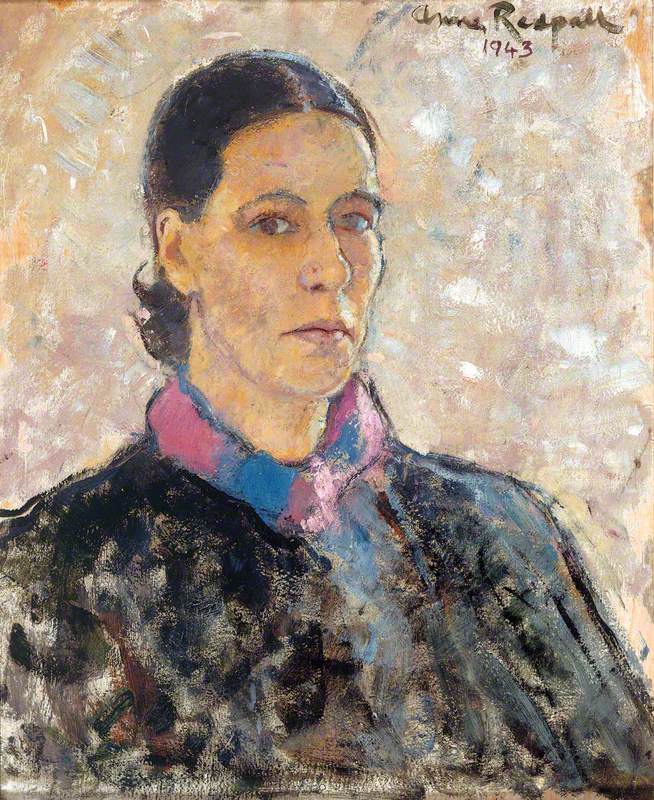

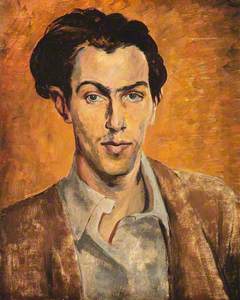

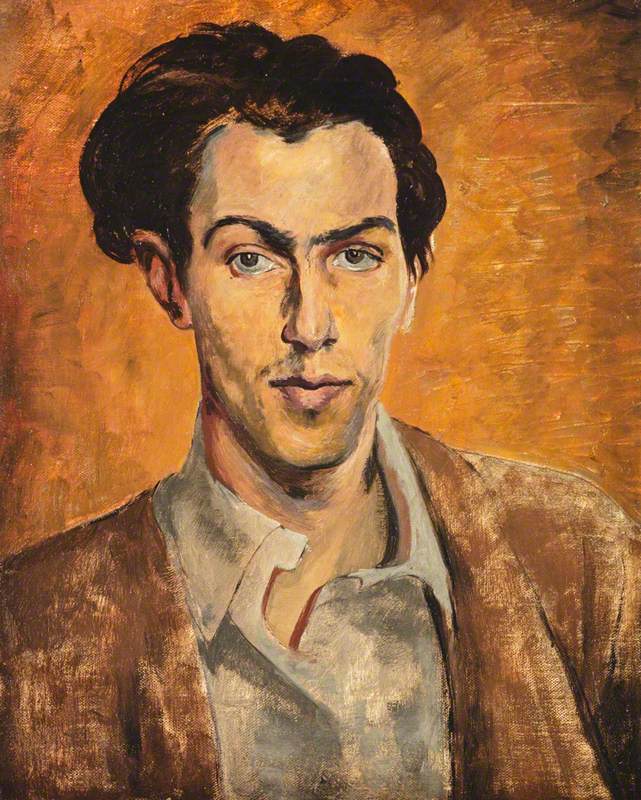

Robert Colquhoun (1914–1962), Artist, Self Portrait c.1940

Robert Colquhoun (1914–1962)

National Galleries of ScotlandThe biographies of Colquhoun and MacBryde are woven together from the beginning. They grew up just over 20 miles from each other, in rural Ayrshire, both in working-class families. Their backgrounds continued to influence them for the rest of their careers. MacBryde moved to Glasgow to study at the School of Art from 1932–1937 and met Colquhoun, who won a scholarship to study there in 1933, a year later. From that point onwards they became inseparable.

Colquhoun and MacBryde were taught by painter and printmaker Ian Fleming, and it is likely that Fleming painted this portrait of them together during their time together at the GSA.

Colquhoun won the GSA's travelling scholarship in 1938. Realising that Colquhoun would likely split the money between himself and MacBryde, additional funds were provided so that the pair could travel together. We can only guess the extent to which their relationship was known about, but it was clearly viewed as something to be encouraged. Their tour took them around Europe, but was cut short by the outbreak of the Second World War.

Both artists continued to paint during the war, primarily as non-commissioned war artists.

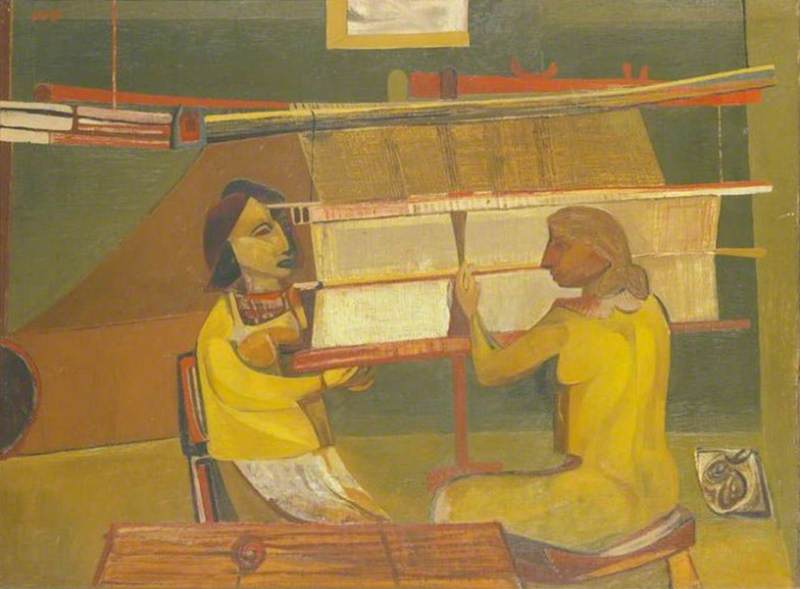

The painting below, Weaving Army Cloth (1945), was Colquhoun's only commission from the War Artist's Advisory Committee. During this time, their work primarily focused on the impact of the war on the home front.

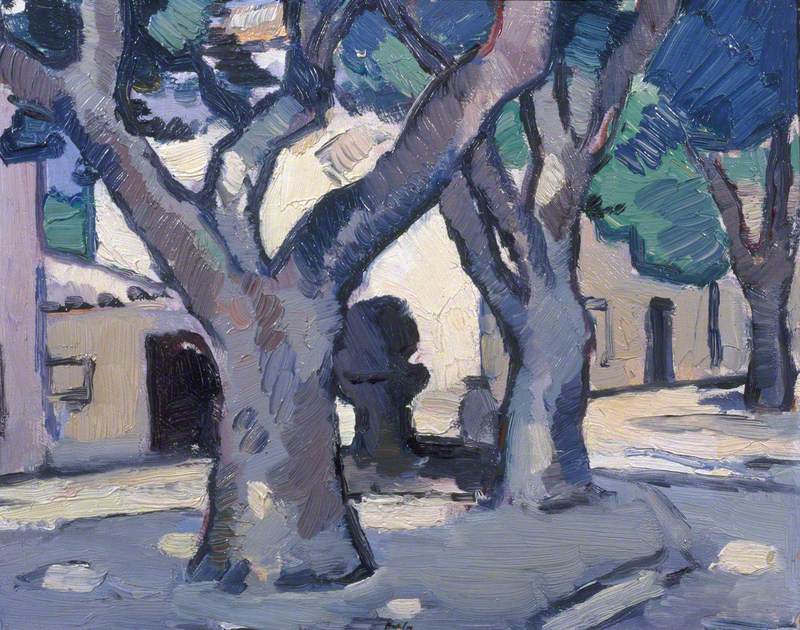

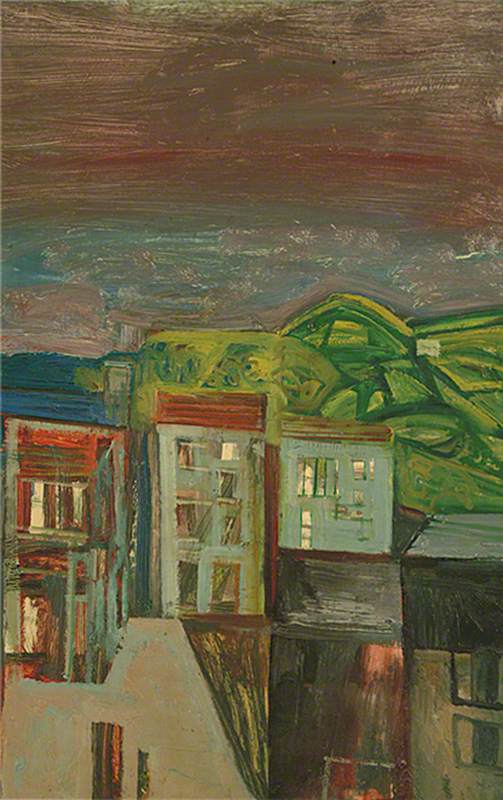

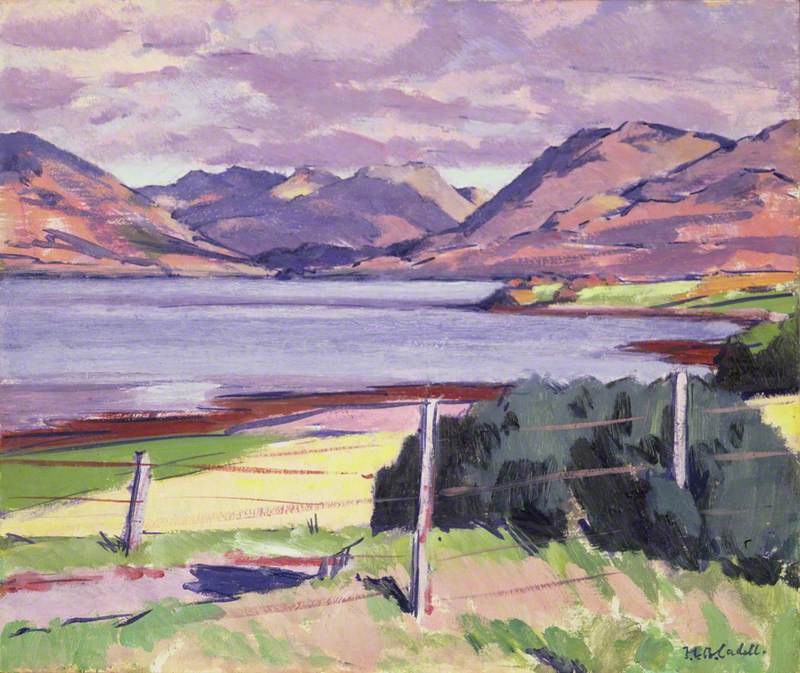

Art historian, Sophie Hatchwell, has compared MacBryde's landscapes at this time to Paul Nash's work during the First World War, noting the similarity in their uncomfortably anthropomorphic surroundings.

They relocated frequently during the war but ended up settling together in London in 1941.

Colquhoun's 1943 painting, The Lock Gate, has a preparatory study painted by MacBryde for his work The Courtyard on its verso side.

Their works are inscribed on each other, a testament to the intimacy of their practices.

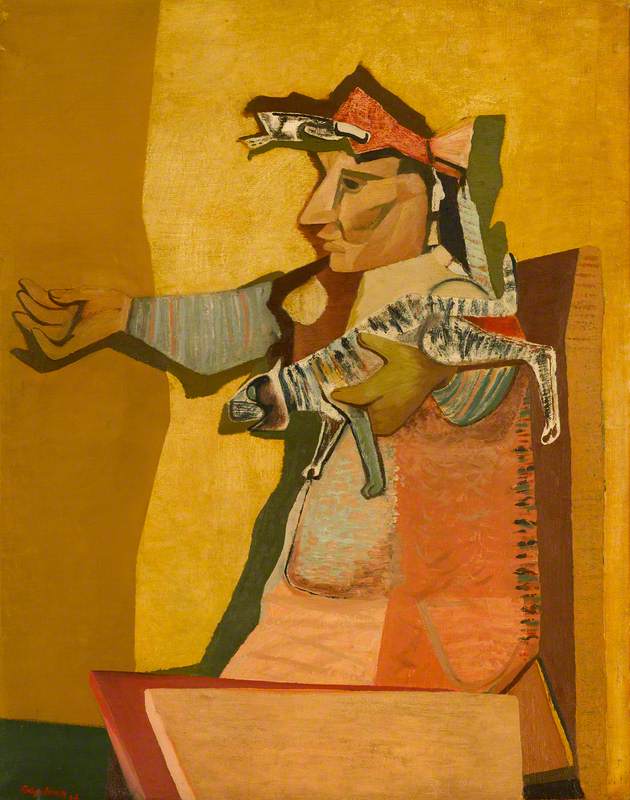

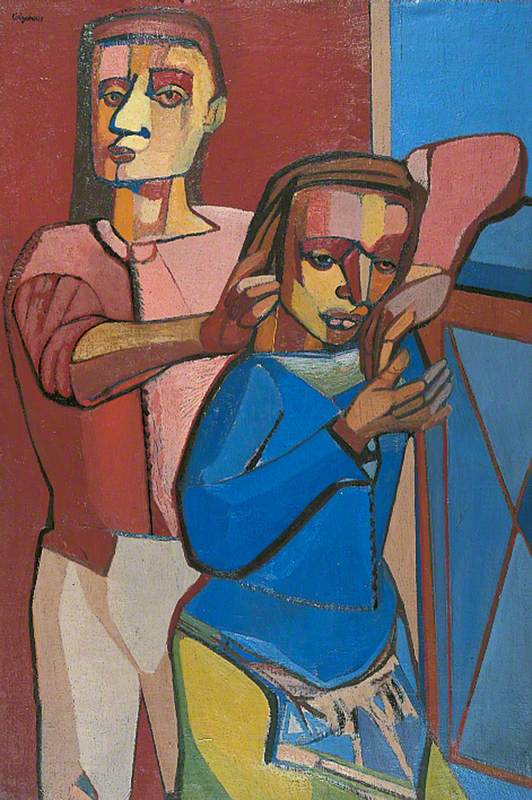

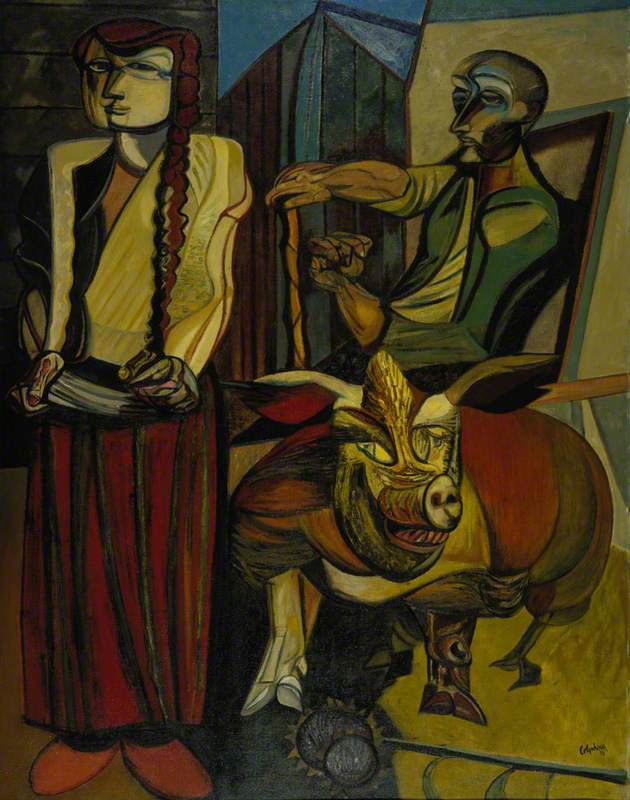

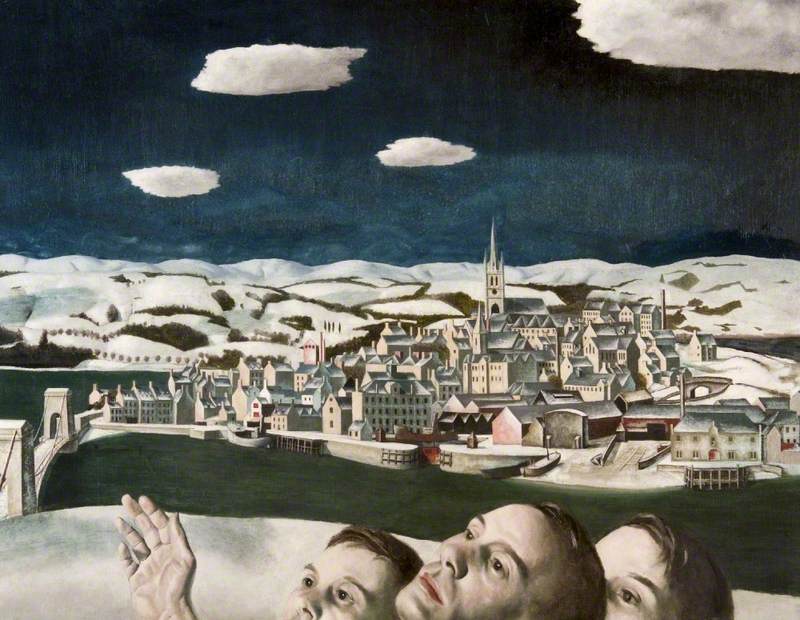

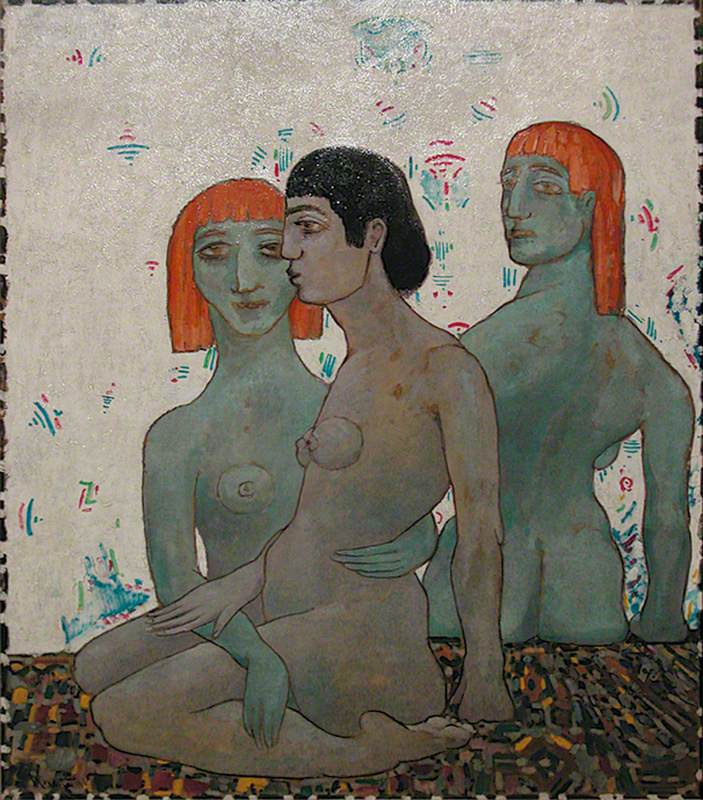

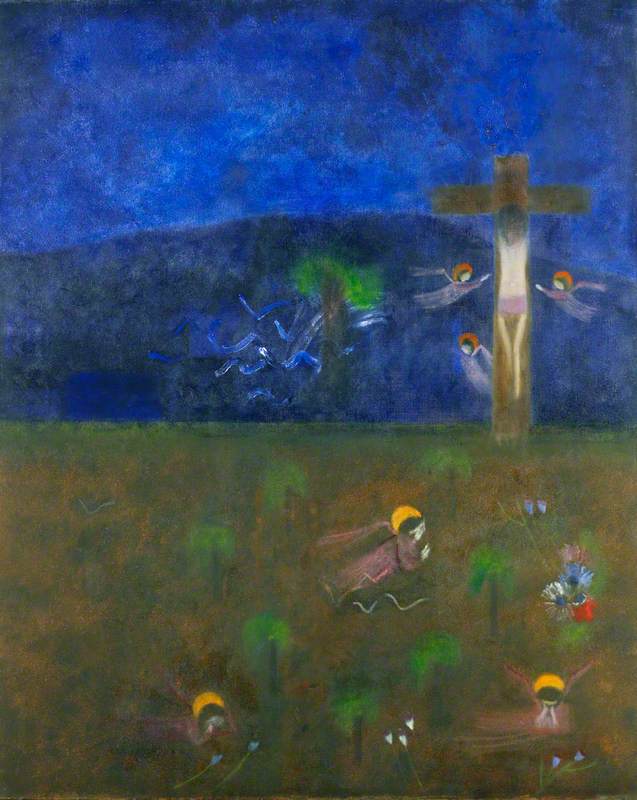

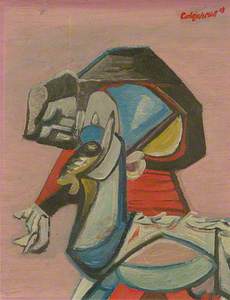

Whilst Colquhoun and MacBryde's landscapes have been classed as neo-Romantic, their figures and still lifes were part of a response to a wider artistic development across Europe.

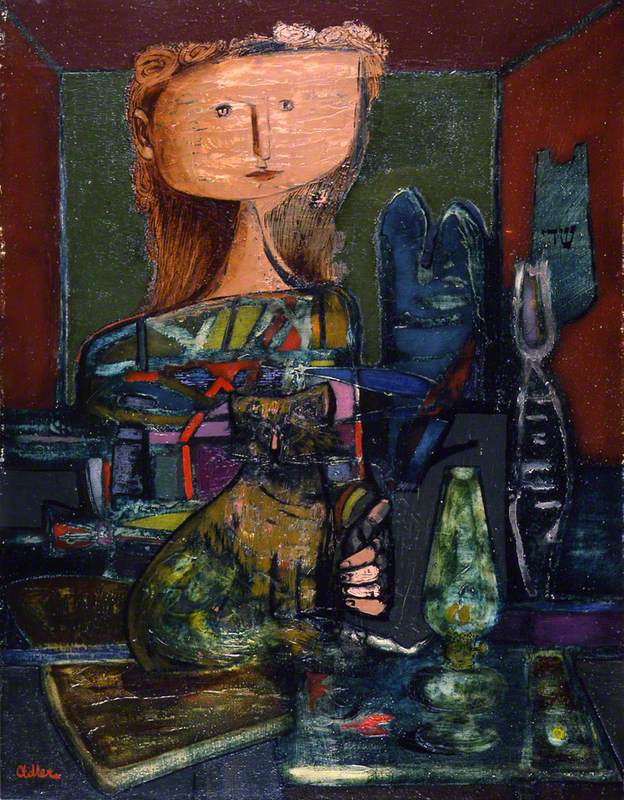

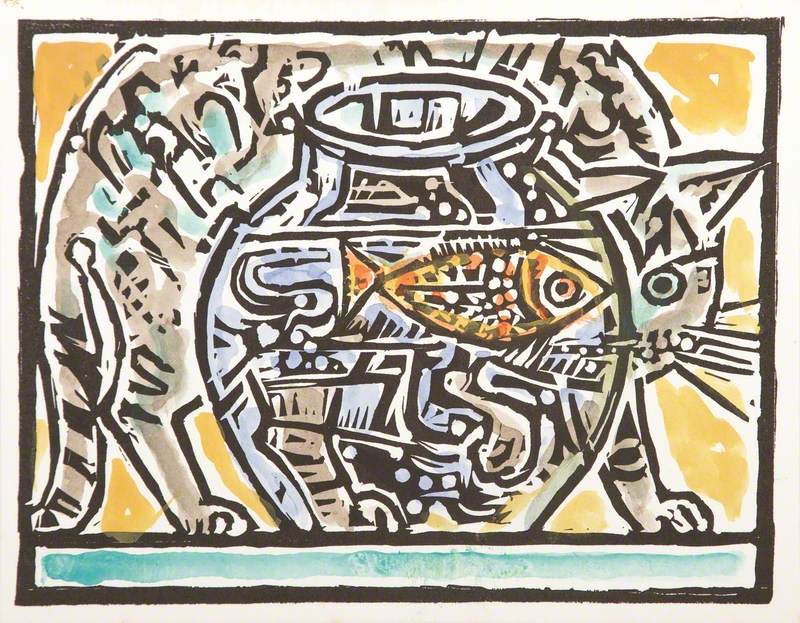

Mentored by Jankel Adler, with whom they shared a studio in London, the influence of Cubism and Expressionism is clear in both their works.

However, they were also associated with John Minton and Wyndham Lewis of the London Group, which had officially formed in 1913 and still exists today.

Under the patronage of the esteemed art collector, Peter Watson, affectionately described by writer Evelyn Waugh as 'a pansy of means', Colquhoun and MacBryde's reputations as artists continued to grow.

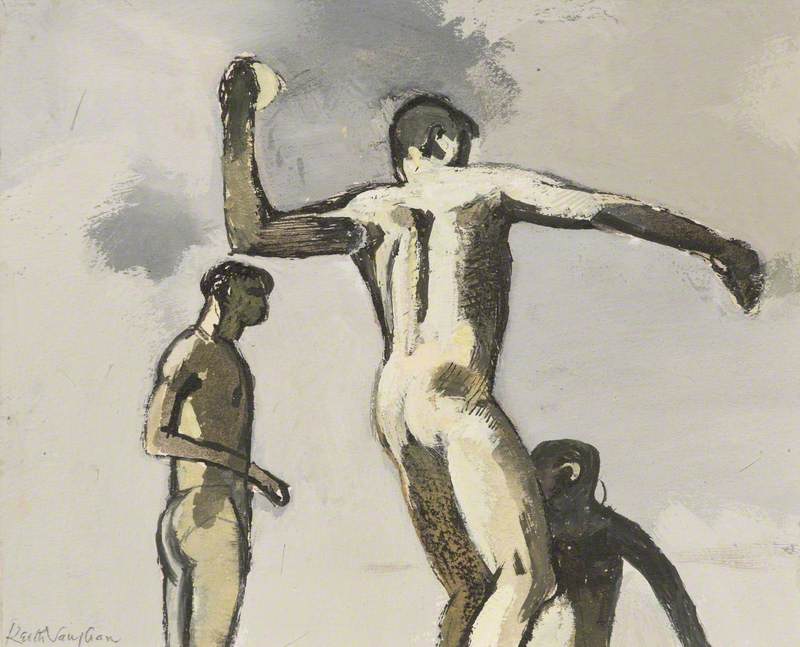

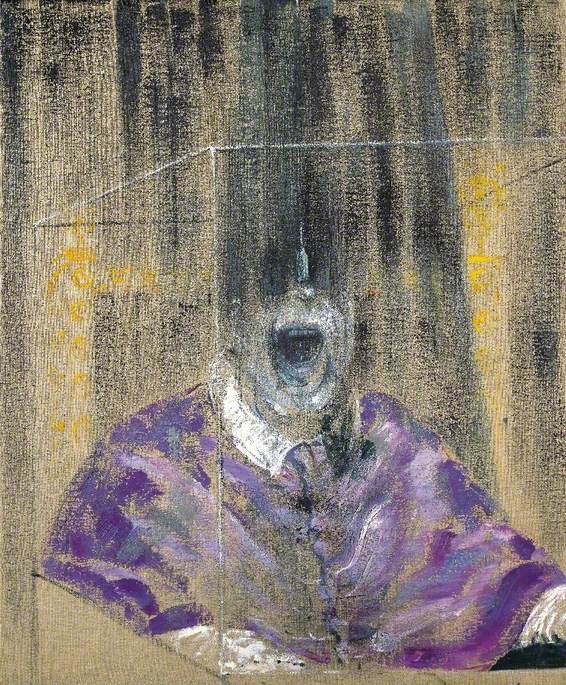

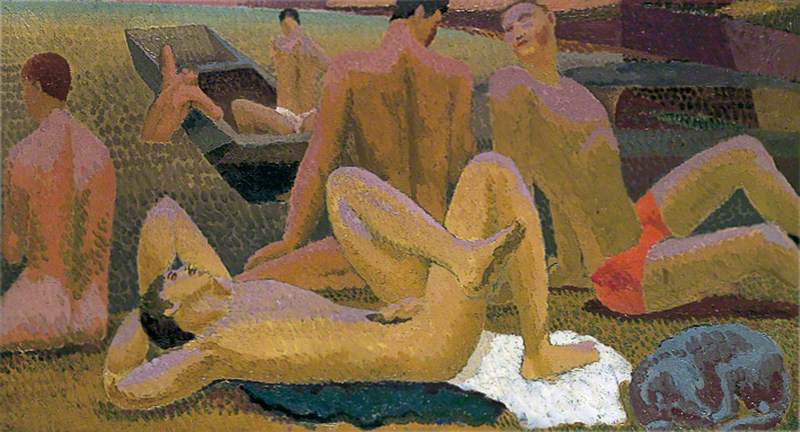

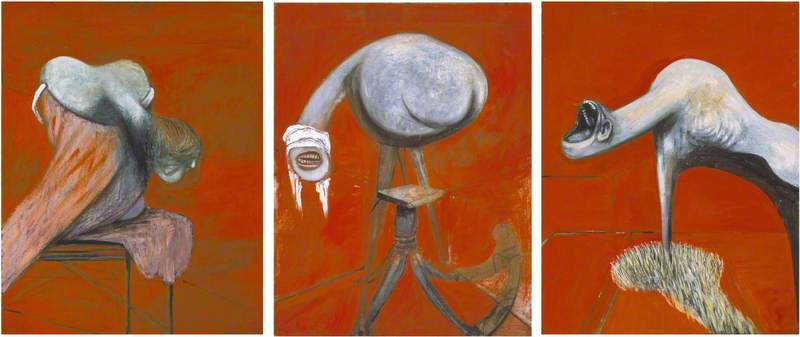

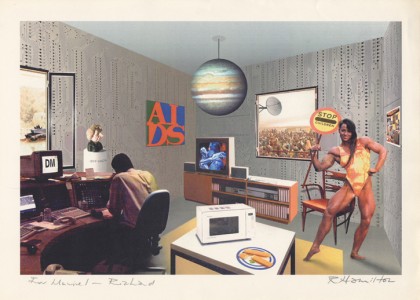

The two Roberts' move to London landed them at the centre of late 1940s queer urban culture, and soon 'The Golden Boys of Bond Street' were associated with fellow Bohemian artists such as Keith Vaughan, Francis Bacon, and Lucian Freud. These artists would later become known for varying degrees of homosexual content in their own works.

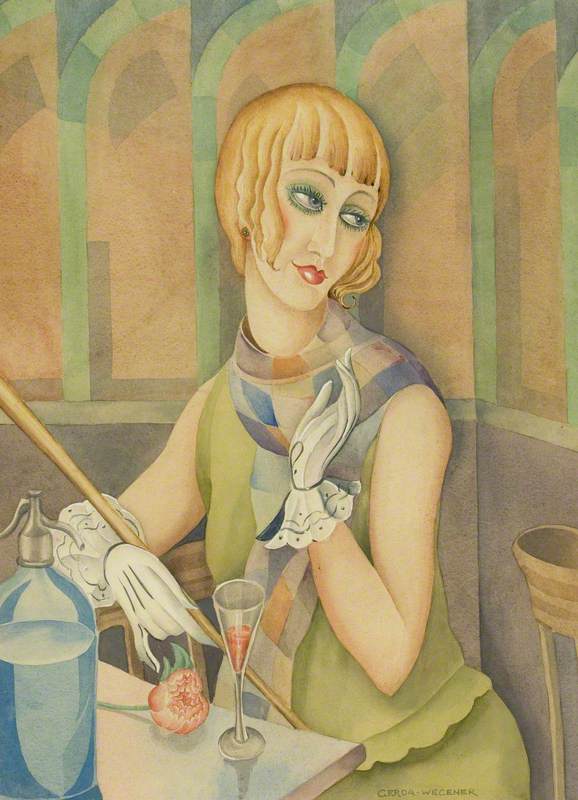

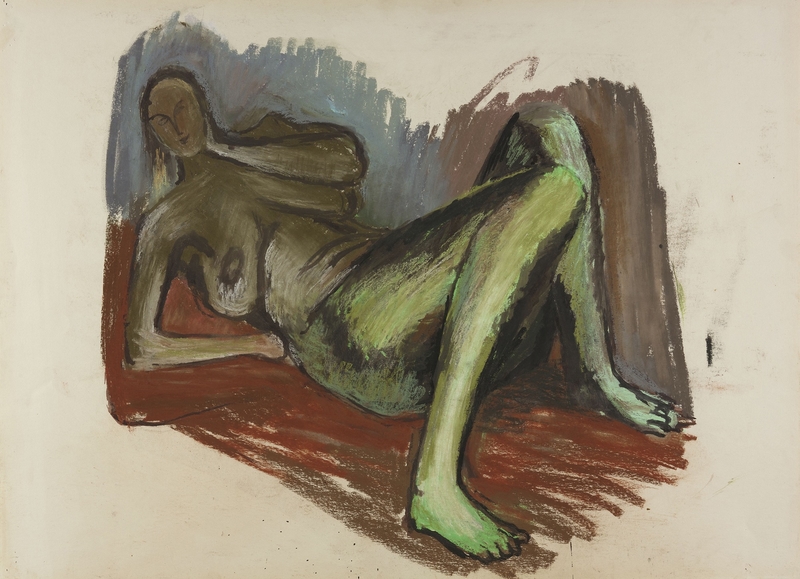

Compared to their artistic contemporaries, Bacon and Vaughan, the subject of sexuality appeared to be less prominent in the works of MacBryde and Colquhoun.

However it is possible to trace their relationship when looking at Colquhoun's many paintings of couples. Often depicting androgynous figures, one can interpret Colquhoun's subjects as reflections of himself and MacBryde. This leads to questions about how we categorise art into what is ostensibly 'queer' and what isn't.

In short, is it possible to read queerness in works of art?

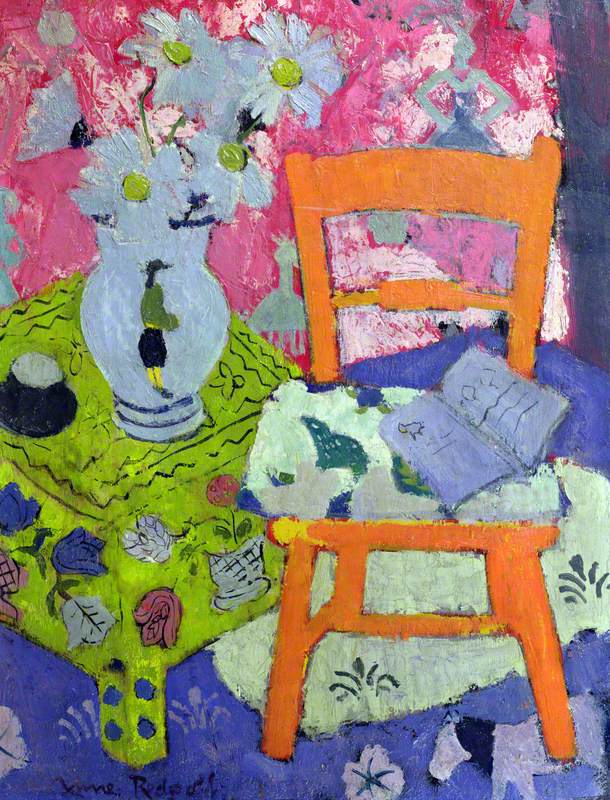

Although clear similarities are visible in the styles of Colquhoun and MacBryde, there are also distinct differences between their works.

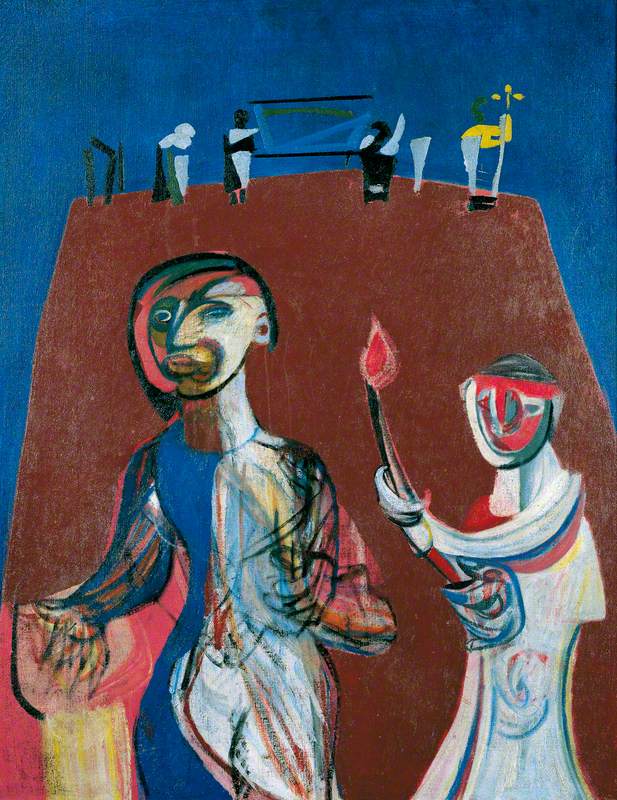

Whilst working closely together throughout their lives, the pair rarely collaborated on paintings, preferring instead to work together on theatrical design, including creating pieces for Leonide Massine's ballet Donald of the Burthens in 1951.

One example belonging to the Scottish National Galleries includes this costume for a peasant woman, as well as the work below in Manchester Art Gallery.

© the artist's estate / Bridgeman Images & © the artist's estate. Image credit: Manchester Art Gallery

Costume for Donald (in a Palace Scene) 1948–1952

Robert Colquhoun (1914–1962) and Robert MacBryde (1913–1966)

Manchester Art GalleryThe more reserved of the two, Colquhoun preferred figures, and his palette is often considered bolder, and his composition more sophisticated.

Whilst Colquhoun was perhaps more famous, this seemed to garner little antipathy from MacBryde, who was happy to play a supporting role.

MacBryde himself favoured the still life – his friend Anthony Cronin said that his 'feeling for the physical reached out to embrace the most trivial things.' This becomes very clear in his tender contemplation of a cantaloupe in a 1959 BBC short film directed by Ken Russell.

The Roberts did not live a life of pure domestic bliss – there are plenty of reports of their fighting, financial difficulties, and heavy drinking, glimpses of their decline to come. As their money and popularity began to decline in the early 1950s, they decided to relocate again. At one point they looked after the four children of the writer Elizabeth Smart, who in a gesture of friendship suggested they move into her house at Tilty Mill in Essex, while she worked as a copywriter in London.

The photograph above captures the two Roberts in 1953, alongside their friend Cedra Obsbourne and the children of Smart and her partner George Barker.

This work below was painted around the same time, during Colquhoun's stay at Tilty Mill.

Despite their rocky moments, Julian McLaren-Ross believed that 'basically nothing could separate Colquhoun and MacBryde except what finally did: against which not even they were proof.'

In 1962, Colquhoun died in MacBryde's arms (most likely due to alcoholism). MacBryde died only four years later in a traffic accident.

Their shared lives are remembered and reflected by their art, a testament to their Bohemian lifestyle and quiet, queer domesticity.

Eleanor Affleck, freelance writer and historian

Further reading

Roger Bristow, The Last Bohemians: The Two Roberts – Colquhoun and MacBryde, 2020

Matt Cook, Queer Domesticities: Homosexuality and Home Life in Twentieth-Century London, 2014

Maria Fusco, 'The Two Roberts: Robert Colquhoun & Robert MacBryde', review for Frieze, 2015

Sophie Hatchwell, 'Letters from the Home Front: The Alternative War Art of Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde, 1940–1945' in British Art Studies, 2019