On Sunday 7th June 2020, people across the UK watched as #BlackLivesMatter protesters toppled a nineteenth-century statue of Edward Colston (1636–1721), a merchant who amassed a vast fortune by trafficking people from West Africa to the Americas as part of the transatlantic slave trade.

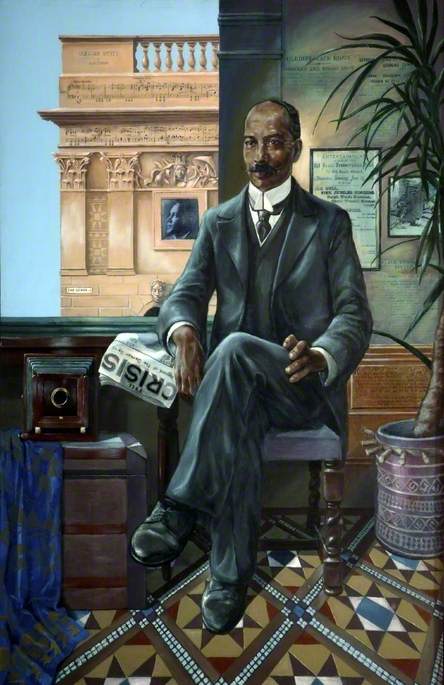

Edward Colston (1636–1721)

1895

John Cassidy (1860–1939) and Coalbrookdale Foundry (active 1709–2017)

The 5.5-metre (18 ft) bronze monument to Colston has stood in central Bristol since 1895, during the pinnacle of imperialism under the reign of Queen Victoria. Bristol, an important merchant port city, was a central hub of colonial trading from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries. Some of the first colonial voyages set sail from Bristol to the Americas in the late fifteenth century.

In the 1990s, Colston's role in the slave trade was fully exposed to the public, leading to fierce arguments in Bristol and calls for the statue's removal. Until then, historians had largely portrayed Colston favourably, as a successful tradesman who had become a generous philanthropist later in life. As a reflection of his charitable work, Bristol's concert hall is named after him, as well as an avenue and several schools in the area (some have been renamed).

As the historian Olivette Otele has noted, in 1996, the city of Bristol celebrated its maritime past by highlighting 'key explorers', while forgetting to mention their involvement in colonial conquests and slavery. This led to the 1999 exhibition on 'Bristol and the Slave Trade' at the Bristol Museum, which until 2006 was on display at the Bristol Industrial Museum (now the site of M Shed). Madge Dresser has written more about Bristol's link with the transatlantic slave trade on Bristol Museums' site.

Edward Colston (1636–1721)

1895

John Cassidy (1860–1939) and Coalbrookdale Foundry (active 1709–2017)

The unceremonious removal of Colston's statue has sparked much celebration. It has also directed a spotlight on questions about how we teach colonial history in schools, and the effectiveness of twenty-first-century 'cancel culture'.

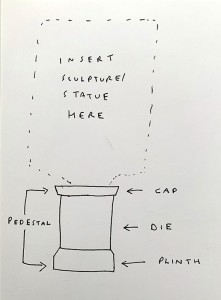

If we remove history, how will we remember our past, learn from it, and be able to criticise its shameful aspects? The historian Françoise Chaoy reminds us that the word 'monument' derives from the Latin 'monumentum' meaning to remember and 'monere', meaning to warn or advise.

The toppling of Edward Colston's statue is not an attack on history. It is history. https://t.co/saJu4zHsZk

— David Olusoga (@DavidOlusoga) June 8, 2020

The dismantling of Colston's statue has definitely served as a powerful symbol of protest. It has reminded the broader public of the brutal realities of slavery, and introduced them to Colston himself, who was less well known outside Bristol.

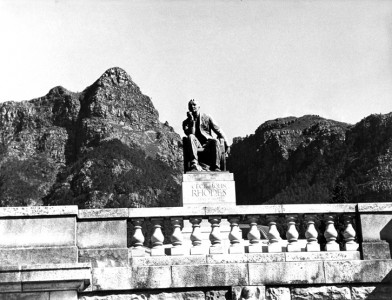

The toppling of the statue follows in the wake of the #RhodesMustFall campaign in South Africa (and later at Oxford University), where protesters called for the removal of a monument to Cecil Rhodes – a man who once said 'the more of the world we [the British] inhabit the better it is for the human race.' Today he has perhaps become the embodiment of colonial, racist attitudes in the popular imagination.

To confront the UK's past through our art and sculpture, we need to understand who Edward Colston was, and decide how to critically frame artworks commemorating him in public collections.

Edward Colston was born on 2nd November 1636 in Temple Street, Bristol. The eldest of eleven children, he grew up in a wealthy merchant family. His father, William Colston, worked as an apprentice with Richard Aldworth, one of the wealthiest Bristolian merchants of the era.

During the English Civil War, the Colston family moved to London, where Edward was educated. He spent most his life in the capital, establishing himself as a trader in textiles, and joined the Mercers' Company through which he began trading with Spain, Portugal, Italy and Africa.

London was a major slaving port for most of the seventeenth century and the largest commercial centre of slave trading up until the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade in 1807. It wasn't until 1834 that enslaved Africans in the British colonies were given their freedom. Even after this date, segregation and discriminatory policies and practices continued across the British Empire, making life incredibly difficult for formerly enslaved individuals and their descendants.

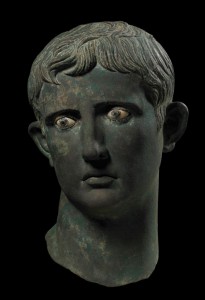

In 1680, Colston joined the Royal African Company (RAC), a mercantile trading company set up by the Stuart royal family and City of London merchants to oversee trading in West Africa.

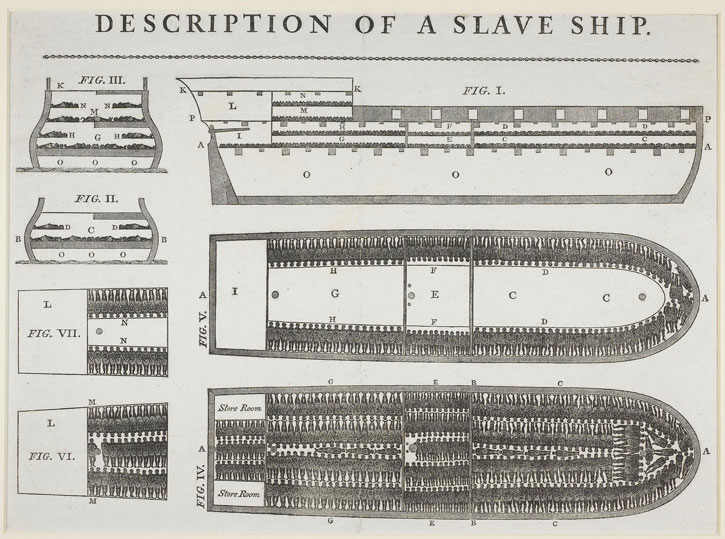

The RAC shipped more African individuals as slaves to the Americas than any other institution during the history of the Atlantic slave trade. Colston served on its management board and developed extensive links with the sugar colony of St Kitts in the Caribbean.

Other notable investors in the RAC included Charles II, the philosopher John Locke, the diarist and Member of Parliament Samuel Pepys, Mayor of London Sir Robert Clayton, statesman George Villiers, and William III – as well as many other affluent men in powerful positions.

Colston's ships sent more than 100,000 men, women and children from Africa to the Americas between 1672 and 1689, all of whom had the company's initials 'RAC' branded onto their chests. We know that enslaved people were typically exposed to appalling and dehumanising conditions on the trading ships, many dying before reaching the coast of the Americas. It is estimated that 20,000 individuals died during the crossings organised under the supervision of Colston.

After amassing a huge fortune on the back of slavery, Colston retired from business in 1708. He turned his attention to charitable work, fashioning a public image as an important philanthropist. He donated sizeable amounts to charities, schools and hospitals in Bristol and London before briefly serving as MP for Bristol in 1710.

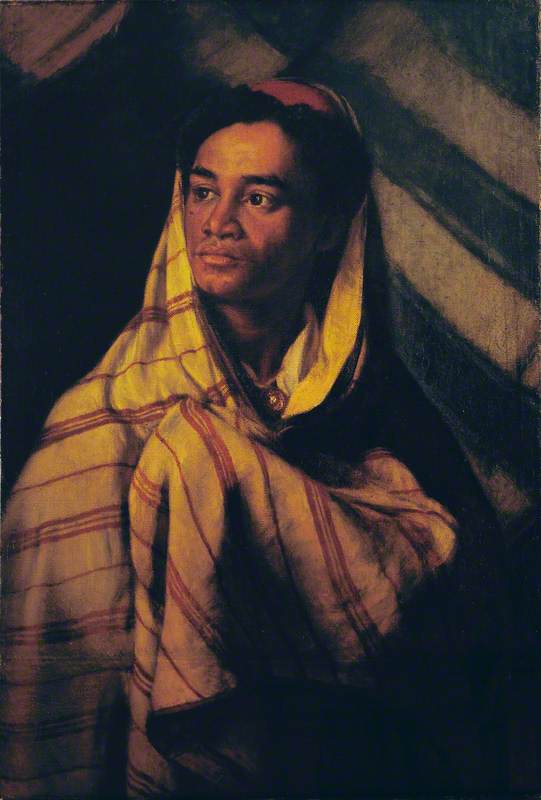

Well-known artists such as those in the circle of Godfrey Kneller – court painter to Charles II – painted his portrait in the early 1690s. This portrait after Peter Lely (1618–1680) is also believed to be of Colston. It belongs in the collection of the Society of Merchant Venturers, an organisation of which Colston was a member.

Portrait of an Unknown Gentleman in Blue

(said to be Edward Colston) c.1700

British School

Those artists and sculptors commissioned to portray him helped to shape his image for posterity as a great man and an important benefactor.

On 11th October 1721, Colston died at his home in Mortlake in Richmond, London. He left detailed instructions for his funeral. With pomp and ceremony, his body was carried in a hearse from London to Bristol.

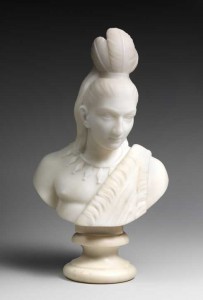

Edward Colston (1636–1721)

c.1726

John Michael Rysbrack (1694–1770)

The effigy of his tomb was executed by artist John Michael Rysbrack based on Jonathan Richardson the elder's portrait of him in the Council House, Bristol.

One year after his death, published descriptions of him declared him to be 'the brightest Example of Christian Liberality that this Age has produced both for the extensiveness of his charities and for the prudent regulation of them.'

The Death of Edward Colston

c.1844

Richard Jeffreys Lewis (1822/1823–1883)

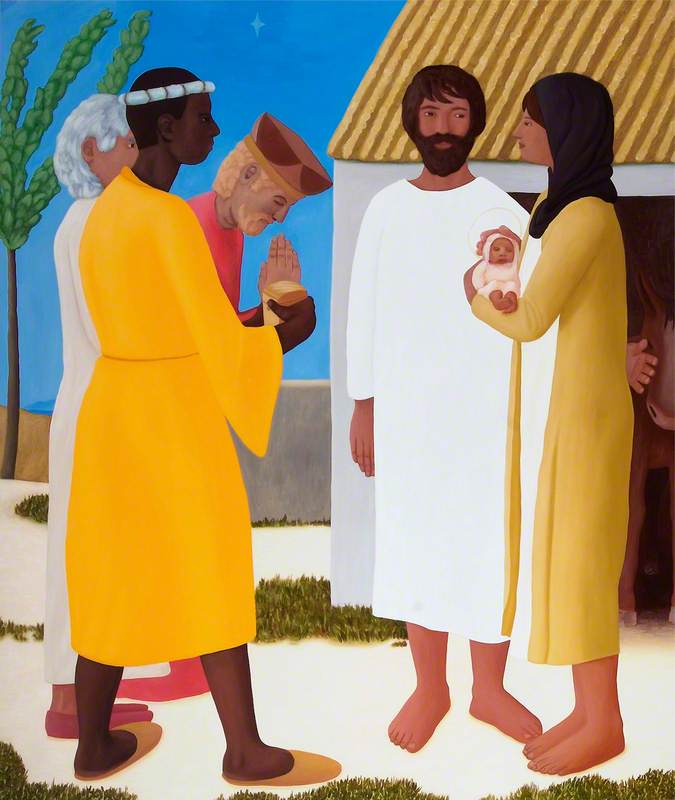

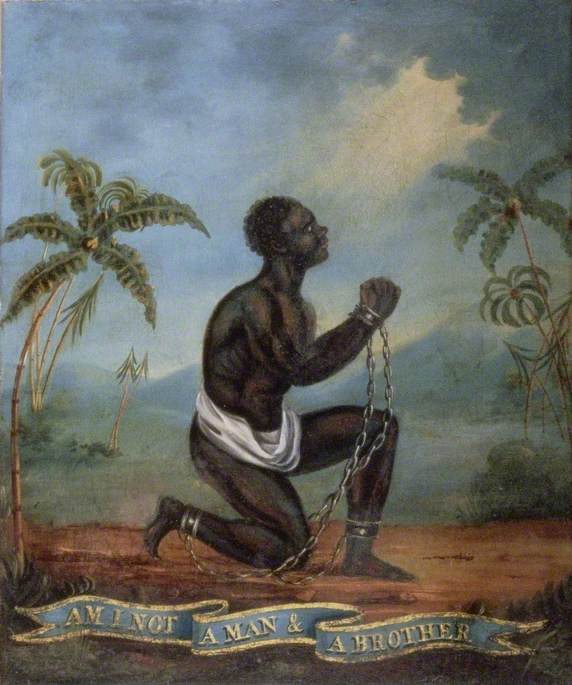

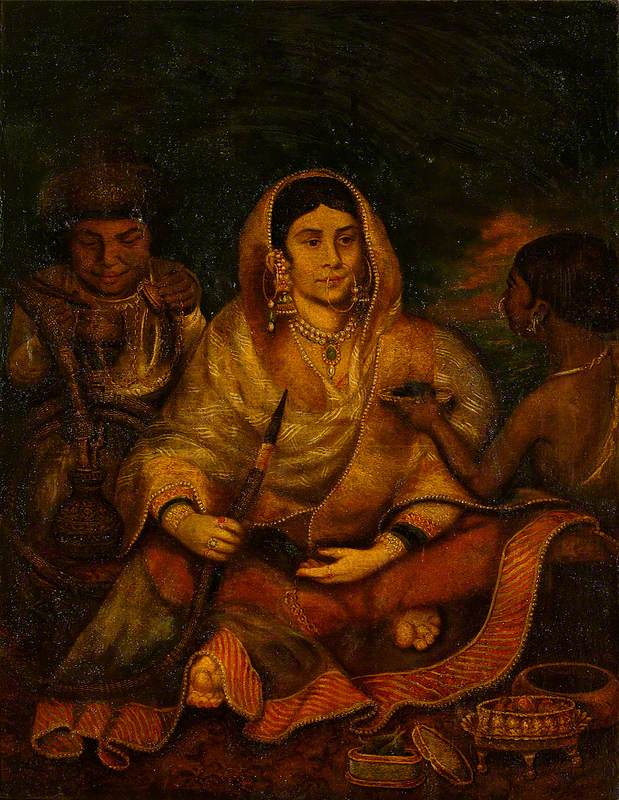

Nearly a century after his death, this invented image of The Death of Edward Colston was painted by Richard Jeffreys Lewis (1822–1883). It belongs to the collection of Bristol Museum & Art Gallery and is deeply unsettling to our contemporary eyes.

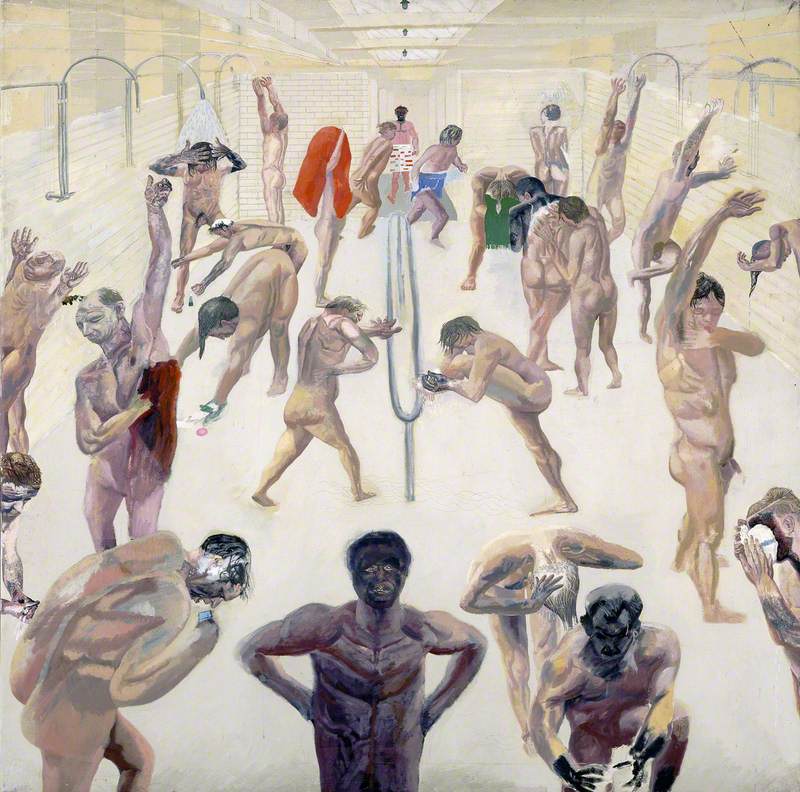

On his deathbed, Colston is presented as a Messiah-like figure. A black woman kneels before his deathbed and kisses his hand. Historians believe Colston did have a personal servant, who was almost certainly an enslaved African. This was a common occurrence for affluent, aristocratic men of the era and is reflected in countless paintings in UK collections, for example, a painting of Sir William Young and his family.

As Elizabeth Kowaleski Wallace argues, this rendering is carefully manufactured to resolve 'any questions of Colston's culpability by showing the slave as grateful to her dying master.' (source: Commemorating the Transatlantic Slave Trade in Liverpool and Bristol, p.62).

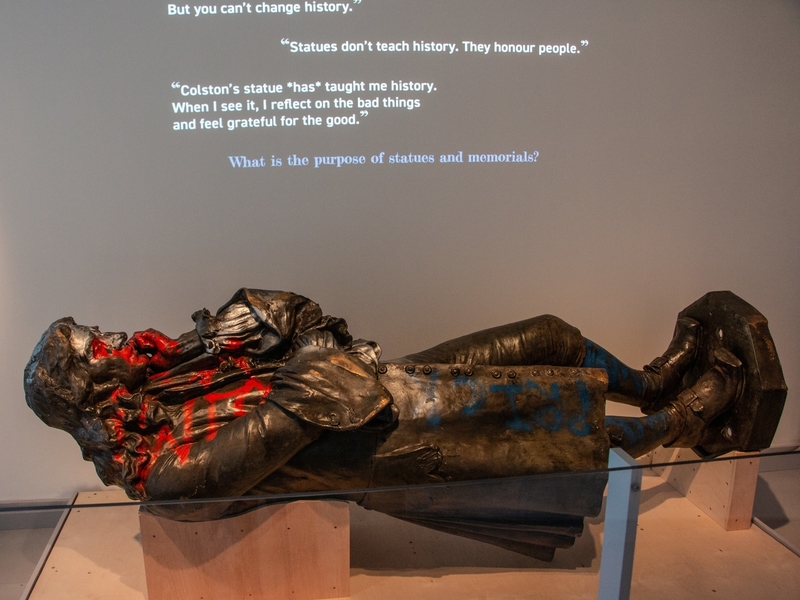

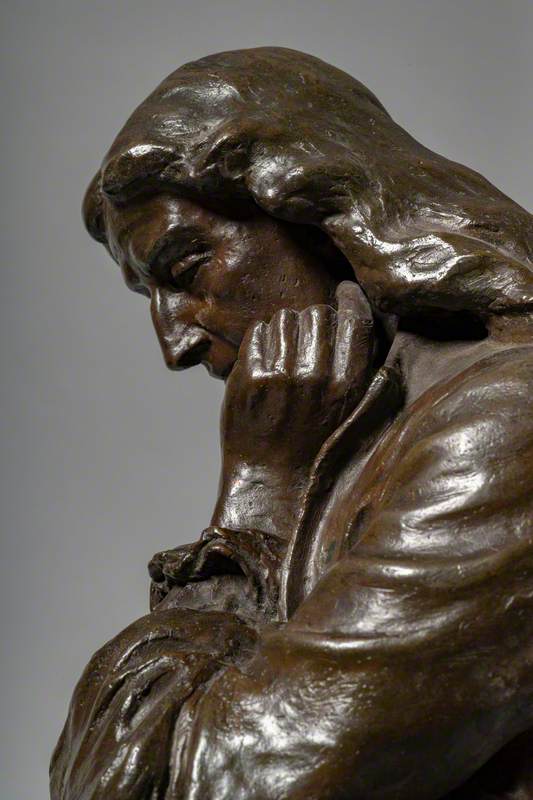

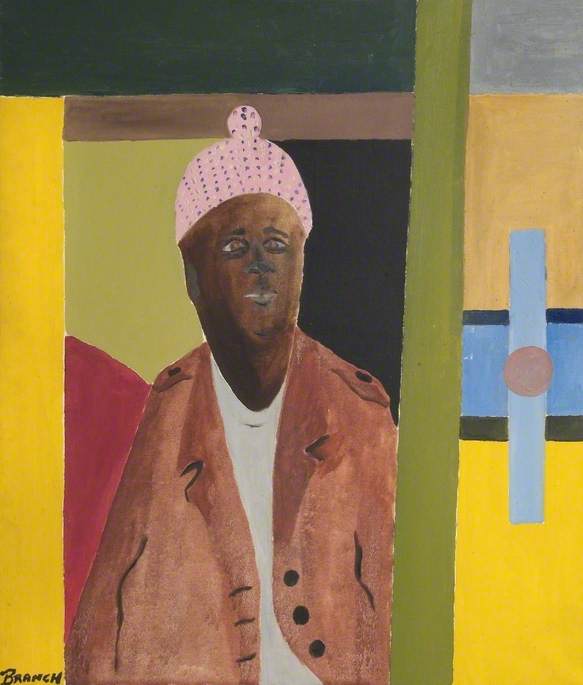

John Cassidy's (1860–1939) smaller version of the controversial larger civic monument is housed in the Bristol Museum & Art Gallery today. In 1895, the Mayor of Bristol, W. H. Davies, unveiled Cassidy's public monument to late Victorian audiences. In 1977, it was designated a Grade II listed structure.

The monument's original plaque bore the words: 'Erected by citizens of Bristol as a memorial of one of the most virtuous and wise sons of their city.'

Since 2018, Bristol City Council had been planning a second plaque which would highlight Colston's involvement in the slave trade. Historians criticised the new proposed wording, with figures such as Madge Dresser claiming it was a 'sanitised' version of history. Bristol's Mayor, Marvin Rees, also criticised the wording, and ultimately vetoed it.

Even though the slave trade was abolished over 200 years ago, Britain's towns and cities are still punctuated with public statues of those who were slave traders and those who made money from its inhumanity.

Our nation's inheritance of art and sculpture should form part of the urgent and wider conversation that we need to have about how to address the shameful legacies of the transatlantic slave trade today. Once again, it raises the pressing and important question about whether colonial history should be a mandatory part of the school curriculum.

What certainly remains clear is that Colston's won't be the last civic monument to be questioned, challenged or disgraced. People are noticing and reacting to public sculpture now more than ever before.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

The toppled statue will be on display at M Shed in Bristol in the free display 'The Colston statue: What next?' from 4 June to 5 September 2021

Further reading

Madge Dresser, 'Set in Stone? Statues and Slavery in London' in History Workshop Journal, Volume 64, Issue 1, Autumn 2007, pp.162–199

Olivette Otele, 'Bristol, slavery and the politics of representation: the Slave Trade Gallery in the Bristol Museum' in Social Semiotics, 22:2, 2012, pp.155–172

'BLM protesters topple statue of Bristol slave trader Edward Colston', The Guardian, 7th June 2020

David Olusoga, 'The toppling of Edward Colston's statue is not an attack on history. It is history', The Guardian, 8th June 2020

.jpg)