The Foundling Museum's exhibition 'Portraying Pregnancy: From Holbein to Social Media' (24th January 2020—26th April 2020) considers representations of pregnancy spanning the last 500 years, a topic that has seldom been the focus of museum exhibitions.

In early modern history, a woman's primary function was to be a dutiful wife and fertile mother. Consequently, many spent the majority of their lives pregnant, a state that was kept under wraps and relegated to the feminine, domestic sphere.

The curator of the exhibition, Karen Hearn, highlights a curious contradiction: although pregnancy underpinned much of early and modern European life, few surviving portraits acknowledge this uniquely feminine disposition.

Portrait of an Unknown Lady

c.1595

Marcus Gheeraerts the younger (1561/1562–1635/1636) (attributed to)

Why was pregnancy scarcely portrayed in both religious and secular traditions of art history? And why did artists ignore, minimise, or even censor signs of pregnancy? Here is a brief art history considering the evolving portrayals of pregnancy throughout the ages.

The maternal archetype

Since time immemorial, humans have revered symbols of fertility and motherhood.

As the influential Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung argued, the maternal archetype has permeated the human 'collective unconscious' for centuries across many cultures. Found in a myriad of visual representations, the maternal figure personified forces of nature – the moon, sea, or earth. She embodied institutions of authority, such as the church or state: for example, Britannia, the female personification of Britain.

Although maternal symbolism is deep-rooted in the human psyche, female subjectivities and the realities of pregnancy have remained shrouded in mystery. This reflected the fact that only by the twentieth century were significant advancements made in regards to women's health and pregnancy.

Before those developments, pregnancy often resulted in fatal consequences. Unsurprisingly, the pain, trauma and death often ensuing from pregnancy were not popular subject matters for artists or their patrons. Therefore, a commissioned portrait of an expectant mother seemed willfully premature, or naively optimistic.

But pregnancy was also a taboo subject due to its affiliations with sex. Pregnancy provided evidence that a woman was fertile, but also sexually active. It undermined a woman's purity and chastity, thus it remained problematic.

The Venus of Willendorf

c.28,000–25,0000 BC, oolitic limestone by unknown artist. Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

That being said, the oldest known work of art showing pregnancy is the Venus of Willendorf, dated between 28,000 and 25,000 BC. The oolitic limestone figurine was discovered in 1908 by the archaeologist Josef Szombathy in southern Austria.

In Greek mythology, pregnancy was depicted through the story of Callisto. A nymph and daughter of King Lycaon, Callisto was raped by Zeus in disguise as Artemis. Subsequently, Callisto became pregnant, much to the displeasure and wrath of her mistress Diana, the goddess of hunting and chastity.

When the Venetian painter Titian depicted the mythological scene, Diana and Callisto, he captured the moment when Diana discovers Callisto's pregnancy.

Amongst Titian's fleshy and voluptuous female nudes – all of whom bear larger stomachs, as this was the prevailing fashion and standard of beauty – Callisto's pregnancy is not easily perceived.

Pregnancy in the Christian tradition

In the Christian tradition, 'ideal' notions of motherhood were disseminated through the figure of the Virgin Mary. A paradoxical symbol, she represented the miraculous – being both a 'Virgin' and a mother.

Although the most famous mother in art history, the Virgin Mary's pregnancy was rarely made the central focus and her bump was usually concealed beneath clothing.

However, portrayals of the pregnant Madonna were produced in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, particularly in rural regions of Italy. The genre of the 'Madonna del Parto' (pregnant Madonna) was believed to boost the fertility of those who pilgrimaged to its sacred location, leaving prayers and ex-votos.

The most famous depiction of the pregnant Madonna was created by Quattrocento painter Piero della Francesca, which still exists in the Umbrian village of Monterchi. It is believed that the fresco was commissioned to continue the rituals of a pagan fertility cult.

Madonna del Parto

c.1460, detached fresco by Piero della Francesca (1416–1492)

Few representations of the Madonna del Parto survived the Counter-Reformation, when the genre was regarded as sacrilegious and promptly removed from chapels and churches across Italy.

Any visual portrayal connecting the body of Christ with the female and mortal body of Mary was frowned upon and became a taboo.

Instead, artists continued to portray the miraculous conception of Christ through the painterly genre of The Annunciation. This scene revealed the moment when the Archangel Gabriel visits the Virgin to tell her she will be inseminated with the Holy Spirit, typically portrayed in the form of a dove or a celestial spotlight.

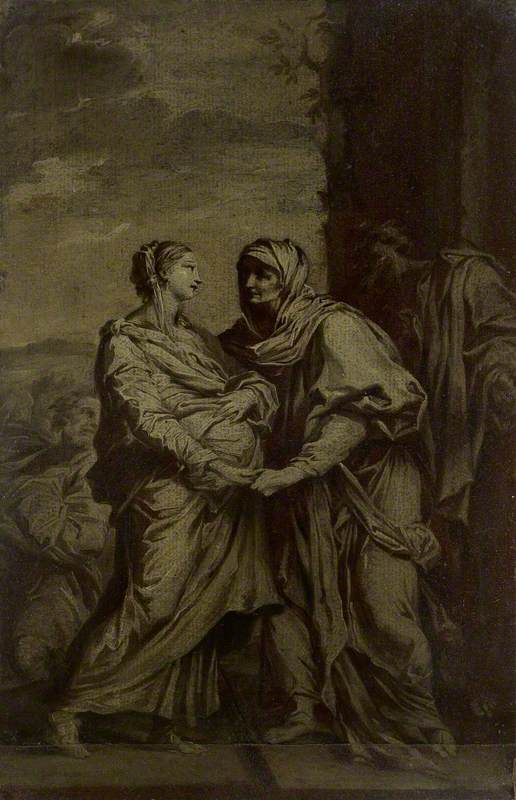

The Visitation of the Virgin to Saint Elizabeth

about 1515

Master of 1518 (active early 16th C) (studio of)

Following The Annunciation, artists depicted the Virgin Mary in scenes of The Visitation where she is often depicted alongside Saint Elizabeth, who either embraces the Virgin or touches her abdomen to indicate pregnancy.

Typically, the Virgin's pregnancy is concealed beneath heavy robes. However, in this seventeenth-century depiction by Carlo Maratta, the Virgin's swollen middle renders her pregnancy clearly visible.

Tudor, Elizabethan and Jacobean portraiture

Protestant attitudes towards pregnancy diverged from Catholic perspectives. While Catholicism proclaimed that chastity and virginity were the ideal states for women, Martin Luther and the Protestant Church decreed that the state of a pregnant woman is a holy one.

During the late Tudor dynasty onwards, representations of pregnancy appeared more regularly in secular portraiture. In fact, curator Hearn has argued that pregnancy portraits even blossomed during this time.

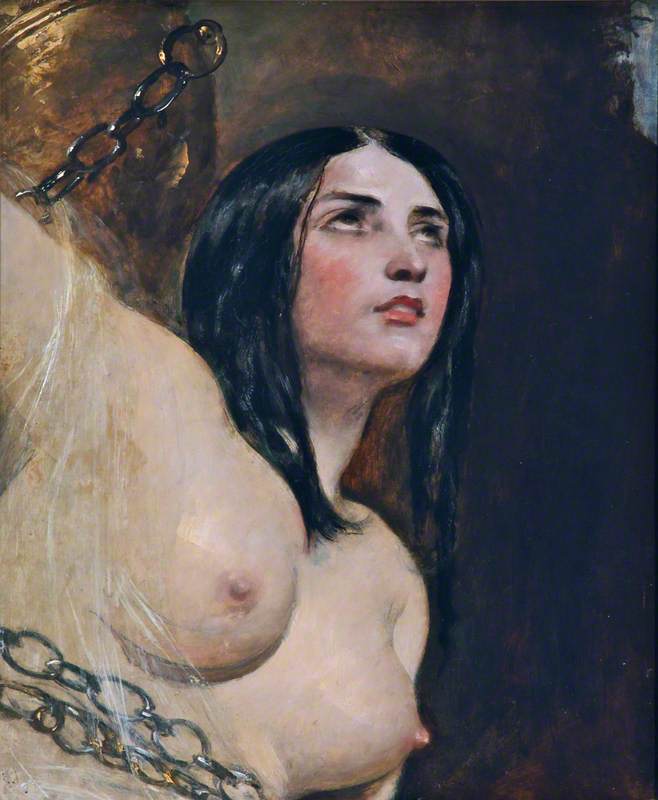

To indicate pregnancy, women were often shown gesturing towards their middle. Pregnancy is clearly visible in this painting of an unknown woman by Marcus Gheeraerts the younger (c.1561–c.1635).

In this portrait of Lady Anne Fanshawe, also painted by Marcus Gheeraerts in 1630, Anne is shown resting a hand against her womb. The first wife of Thomas, 1st Viscount Fanshawe, she became pregnant a few years after their marriage in 1627.

Anne Fanshawe (1607–1628), First Wife of Thomas, 1st Viscount Fanshawe

c.1628

Marcus Gheeraerts the younger (1561/1562–1635/1636)

Gheeraerts depicted her in the later stages of pregnancy. She allegedly died during childbirth the following year.

Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

After the seventeenth century, depictions of pregnancy became rarer. This was perhaps due to a shift in taste, but possibly also a reflection of increasingly conservative attitudes.

The English artist Joshua Reynolds had omitted Theresa Parker's pregnancy in this full-length portrait he completed in 1770. In a letter to the artist, Theresa had referred to her pregnancy, writing: 'I expect you will say I have chose an improper time for the purpose...I am very fat.'

The Hon. Theresa Robinson, Mrs John Parker (1745–1775)

1770–1772

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

Whether due to the instruction of the sitter, or the artist's preference, Theresa's pregnancy is not discernible in this portrait. Once completed it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1773.

Throughout the nineteenth century, portrayals of pregnancy in art history declined. According to Cynthia Northcutt Malone, 'For most of the nineteenth century, in the novel and in bourgeois culture, pregnancy was visible but unspeakable.'

In a new era of Victorian middle-class decorum, open representations and discussions about pregnancy were considered indecorous. Malone points out that in nineteenth-century advice books by medical men, euphemisms were deployed to avoid direct references to pregnancy.

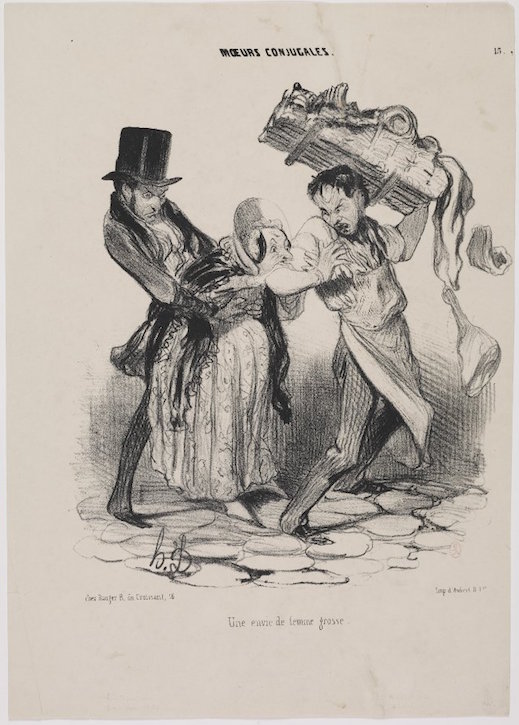

Une envie de femme grosse (Pregnancy craving)

1839, lithograph on paper by Honoré Daumier (1808–1879), printed by Aubert & Cie, published by Bauger et Cie

This French satirical print dated to 1839 is titled Marital conventions: the cravings of a pregnant woman. The lithograph shows a ravenous wife biting the arm of a passing butcher. The horrified butcher spills his loaded tray as the woman's husband holds her back.

Twentieth century and beyond

By the twentieth century, attitudes towards pregnancy changed, with women and male artists capturing the pregnant state in portraiture. For example, Austrian artist Gustav Klimt painted pregnant women and female nudes at the start of the century, seen in works such as Hope I (1903) and Hope II (1907–1908). Klimt's paintings were received with contempt amongst conservative Austrian audiences, who were not used to seeing conflations of female sexuality with pregnancy.

Hope I

1903, oil on canvas by Gustav Klimt (1862–1918)

Women artists in particular – potentially responding to the progressive environments ensuing first- and second-wave feminism – empowered themselves through pregnancy self-portraiture.

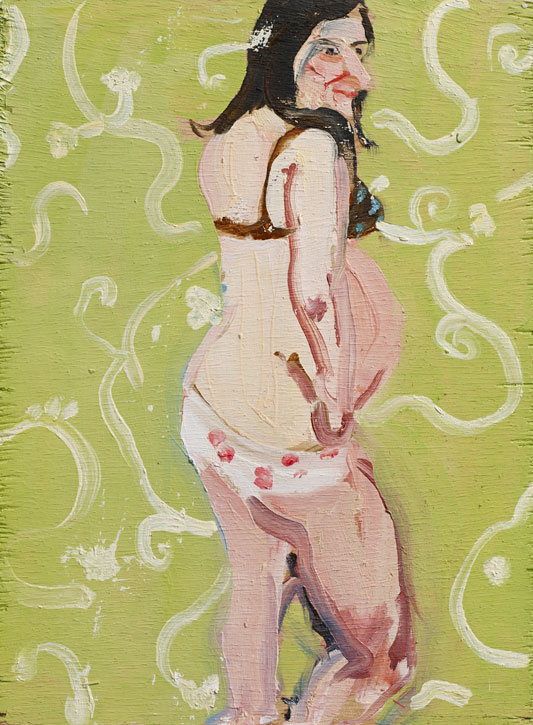

Self-Portrait Pregnant II

c.2004, oil on board by Chantal Joffe (b.1969)

Paula Modersohn-Becker shocked her contemporaries when she painted a series of nude self portraits pregnant, though she would sadly die shortly after giving birth to her first child. Renowned female artists throughout the twentieth century followed in her footsteps, from Ghislaine Howard to Alice Neel, Louise Bourgeois and Chantal Joffe

In an age that (once again) celebrates pregnancy and motherhood, the rules for representing the female experience have been redefined.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

Further reading

Karen Hearn, 'A Fatal Fertility? Elizabethan and Jacobean Pregnancy Portraits', Costume, 2000

Cynthia Northcutt Malone, 'Near Confinement: Pregnant Women in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel', Dickens Studies Annual 29, 2000