‘He paints with such accuracy and cunning that the eye is deceived and truly believes that it is the real thing it sees, not a painting.' – Pietro Guarienti, 1753.

As part of the National Gallery's bicentenary celebrations, a masterful early work by the Venetian view painter Canaletto (1697–1768) is travelling to the National Library of Wales in May 2024 – 80 years after it left London to be kept safe in a slate mine in north Wales during the Second World War. The Stonemason's Yard is one of the most intriguing works in the artist's oeuvre and an excellent demonstration of his immense skill.

Venice: Campo S. Vidal and Santa Maria della Carità ('The Stonemason's Yard')

about 1725

Canaletto (1697–1768)

The work is thought to date to around 1725, though nothing is known about the commission. In his early works, Canaletto adopted a large-scale and dramatic format, with buildings brought right up to the foreground and intense contrasts of light and shade.

This is nonetheless an unusual work for Canaletto; instead of a grand view along the canal, we are presented with the humbler sight of Campo San Vidal. This space has been temporarily converted into a stonemasonry yard, presumably while repairs were undertaken on the church of San Vidal. As with many of Canaletto's paintings, it is populated with tiny vignettes of everyday action which vividly bring it to life.

Antonio Giovanni Canal was born in Venice in 1697, the son of the theatrical scenery painter Bernardo Canal. He trained with his father, distinguishing himself as 'Canaletto', the 'little canal'. In 1719, the pair travelled to Rome to paint stage scenery for operas by Alessandro Scarlatti. A year later, Canaletto returned to Venice where he swiftly became known for his evocative views of the city, featuring precise architectural details, glittering waters and stretches of blue sky.

The Grand Canal, Venice, Looking North East from the Palazzo Balbi to the Rialto Bridge

c.1724

Canaletto (1697–1768)

The genre of view painting ('veduta') was made popular in Venice by Luca Carlevarijs, an artist working just a few years before Canaletto.

The Arrival of the Earl of Manchester in Venice

1707–1710

Luca Carlevarijs (1663–1730)

Canaletto was aware of Carlevarijs's views of Venice and the two artists presumably met. In 1725, Stefano Conti, a textile merchant from Lucca, was encouraged by the artist Alessandro Marchesini to acquire works by Canaletto rather than Carlevarijs as 'His work is like that of Carlevarijs, but you can see the sun shining in it.'

In 1726, Canaletto met Owen McSwiney, an Irishman based in Italy, who changed the course of his career. As well as commissioning two paintings, McSwiney introduced Canaletto to his first English client – Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond – and encouraged him to produce small-scale paintings featuring bright views of Venice for the tourist market.

The Bacino di San Marco, Venice, Seen from the Giudecca

c.1726

Canaletto (1697–1768)

In the eighteenth century, Venice was an essential stop on the Grand Tour, which saw British gentlemen, and eventually women, visit the main cities of Europe to further their education. In this city of fun and festivities, tourists particularly enjoyed the Grand Carnival which ran from 26th December until Lent and involved carnival dress and mask-wearing.

Through McSwiney, Canaletto became acquainted with Joseph Smith, British Consul in Venice. Smith was interested in Canaletto's works as a collector himself but also recognised the market for such city views as souvenirs for Grand Tourists. Smith and Canaletto developed a business relationship that lasted for almost the whole of the artist's life. Canaletto produced works for Smith's house on the Grand Canal which functioned like advertisements for potential clients.

In 1762, Smith's collection of Canaletto's works was acquired by the young George III and remains today in the Royal Collection.

The Mouth of the Grand Canal looking West towards the Carità

c.1729–1730, oil on canvas by Canaletto (1697–1768)

One of Smith's most important commissions in around 1722 was a series of 12 paintings of the Grand Canal, completed over the course of about a decade. Together they provide a visual representation of almost the entire length of the Grand Canal. While they are ostensibly topographically accurate, Canaletto manipulated reality for artistic effect – he expanded perspectives, combined viewpoints, adjusted and eliminated buildings, and brought architecture closer to the viewer.

He is thought to have used an optical device, such as a 'camera obscura', to capture and align buildings, as was common at the time.

Smith displayed the paintings in prominent positions in his house. As they were in a small, portable format, new versions for clients could be easily shipped to England. John Russell, 4th Duke of Bedford, acquired 24 for his 'Canaletto Room' at Woburn Abbey. In 1730, Samuel Hill commissioned two views of the Grand Canal for Tatton Park. On 17th July 1730, Smith wrote 'At last I've got Canal under articles to finish your 2 pieces within a twelvemonth.' Evidently, by this time Canaletto was much in demand.

The Grand Canal, Piazzetta and Dogana, Venice

c.1730

Canaletto (1697–1768)

In 1733–1734, Canaletto finished the Grand Canal series for Smith with a pair of slightly larger paintings which evoked the lively and dazzling atmosphere of the Carnival. The subjects are two of Venice's most famous annual festivals: the return of the Bucintoro (the Doge's Galleon) from the ceremony of the Marriage of the Sea on Ascension Day and the regatta which took place on 2nd February, the feast of the Purification of the Virgin.

The Bacino di San Marco on Ascension Day

c.1733–1734, oil on canvas by Canaletto (1697–1768)

A Regatta on the Grand Canal

c.1733–1734, oil on canvas by Canaletto (1697–1768)

Pairs of works illustrating these festivals became a popular product for Canaletto, with prime examples in the collection of the Duke of Leeds at Hornby Castle by around 1867 (now at the National Gallery, London).

Venice: The Basin of San Marco on Ascension Day

about 1740

Canaletto (1697–1768)

The outbreak of the War of the Austrian Succession in 1740 meant that fewer Grand Tourists could reach Venice. As Canaletto's source of patronage shrunk, he sought new subjects elsewhere. He journeyed up the Brenta Canal, producing paintings, drawings and etchings of the landscape. In 1742, he produced a set of views of Rome for Smith, possibly using drawings produced during his visit in 1719–1720.

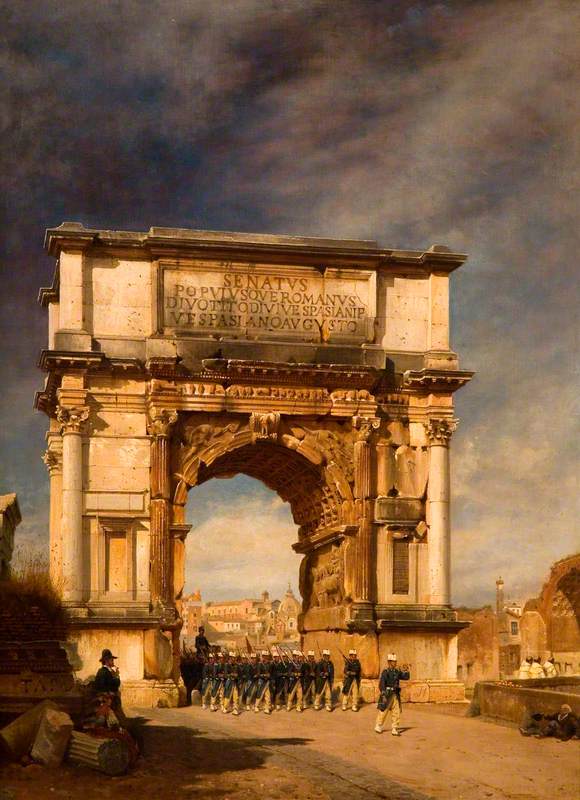

The Arch of Titus

1742, oil on canvas by Canaletto (1697–1768)

In 1746, Canaletto departed for England, providing McSwiney with a letter from 'our old acquaintance the Consul of Venice' asking for an introduction to the Duke of Richmond, his former patron. Canaletto knew that he would find clients interested in his paintings and set to work, producing topographical views of London and country residences, as well as Italian scenes.

Greenwich Hospital from the North Bank of the Thames

c.1752

Canaletto (1697–1768)

In A View of Walton Bridge¸ painted for Thomas Hollis in 1754, Canaletto included a rare glimpse of the artist himself, seated in the foreground sketching the scene.

Canaletto returned to Venice in 1755 where he remained for the rest of his life. In 1760, John Crewe and Reverend John Hinchcliffe came across an old man drawing in Piazza San Marco. When they recognised the hand of the artist as Canaletto, he said 'mi conosce' ('you know me') and invited them to his studio.

Canaletto's late works tend to be darker in tone and on a smaller scale. Whilst he continued to produce popular views of the Grand Canal, he also experimented with new subjects and areas of focus. In these two atmospheric paintings at the National Gallery, Canaletto presents intriguing glimpses of Piazza San Marco from within the architectural structure of a colonnade. He has exaggerated the perspective to a dramatic extent and has yet again populated the scene with a variety of fascinating characters engaged in the tasks of everyday life.

Venice: Piazza San Marco and the Colonnade of the Procuratie Nuove

about 1756

Canaletto (1697–1768)

As Canaletto focused primarily on the tourist market, he was not well recognised in artistic and intellectual circles in Venice and was only elected to the Academy in 1763. The inventory at his death in 1768 reveals a modest lifestyle with few possessions.

View in Venice, on the Grand Canal (Riva degli Schiavoni)

(detail) c.1734–1735

Canaletto (1697–1768)

Canaletto remains most celebrated today for his iconic views of Venice. He evoked the squalor and splendour of the city, the mundanities as well as the festivities. Even in paintings with seemingly the same viewpoint, he conjured up different atmospheres, observing and altering reality, highlighting individual details and adjusting buildings. He offers a unique glimpse into the life, atmosphere and culture of the bustling eighteenth-century city that was so well-loved by English travellers.

Amy Parrish, Assistant Curator of Paintings at the Royal Collection Trust

Canaletto's The Stonemason's Yard is at the National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth from 10th May until 7th September 2024

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation