Last year, Petrit Halilaj returned to drawings he had created during a very turbulent time in his life. In 1999, when Petrit was 13 years old, Serbian troops landed in his native Kosovo, forcing him and his family to flee to a refugee camp in nearby Albania.

Suddenly, all that was familiar to him was catastrophically destroyed. The Kosovo War (1998–1999) saw Serbian troops up in arms against ethnic Albanian rebels, which ultimately led to the displacement of 1.2 million to 1.45 million Kosovo Albanians during the conflict.

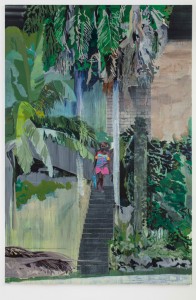

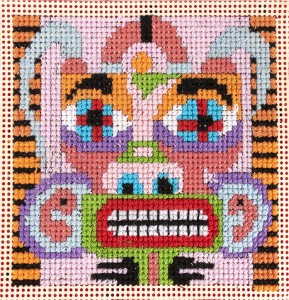

Image credit: Angela B. Suarez

Studio Petrit Halilaj, work in progress for Tate St Ives exhibition, Spring 2021

Halilaj's drawings created at the tender age of 13 marked the beginning of his passion for storytelling. He used the trauma ignited by the war to weave together a narrative of anguish, loss, and broken dreams. Whilst at the refugee camp, Halilaj met an Italian psychologist named Giacomo 'Angelo' Pol, who was assigned to the camp for two weeks. During his time there, he provided the children in the camp with tools to create art, which helped them to communicate how they were feeling.

Now 22 years later Halilaj, who has presented at the Venice Biennale, Berlin Biennale, Madrid's Museo Reina Sofia and the New Museum in New York amongst other international sites, is showcasing his work in the UK for the first time. Titled 'Very volcanic over this green feather', the exhibition at Tate St Ives refers to the 38 drawings he created as a child, now transformed into an immersive space.

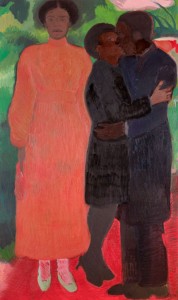

© the artist. Image credit: Matt Greenwood, courtesy of Tate

Installation view of 'Petrit Halilaj: Very volcanic over this green feather'

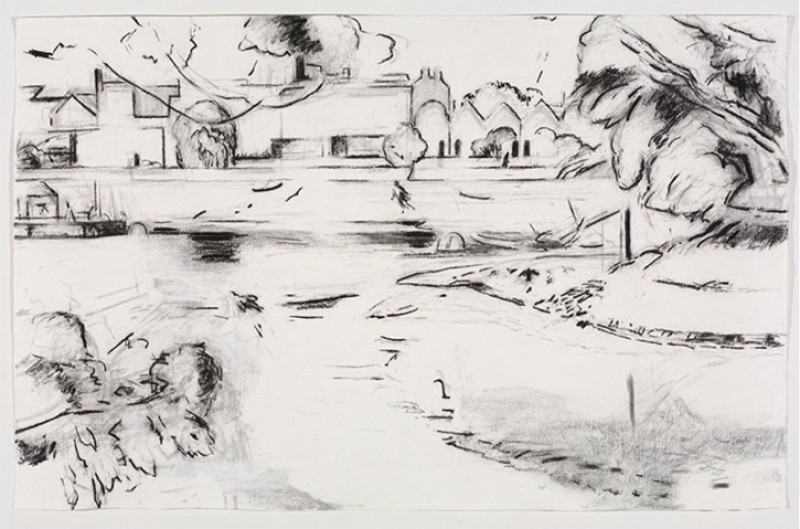

On entering the Tate show you are met with interwoven landscapes, birds, trees, fires – devastation juxtaposed with serenity. Hovering and suspended in mid-air, 83 felt-tip drawings are displayed in fragments, providing the viewer with a wholly immersive experience. The entire exhibition is a meditation on what it means to be a child who has escaped war. At first, it is a room full of bright colours – in homage to Halilaj's childlike innocence at the time of drawing. You may think you've entered a fairytale of some sort, but as you make your way through the room you realise there is darkness awaiting.

Speaking about the space, the artist said: 'The further you go in, the more the story of the war will unfold, and when you reach the other side and turn around, the impression is that of terror'.

© the artist. Image credit: Matt Greenwood, courtesy of Tate

Installation view of 'Petrit Halilaj: Very volcanic over this green feather'

The hanging fragments indicate a static pause, as the pieces are unmoving. It is indicative of how the memories still reside in Kosovo's collective memory. In conversation with Wallpaper* Magazine, the artist said that the show speaks 'to personal and national identity, and what it means on a larger scale.'

© the artist. Image credit: Matt Greenwood, courtesy of Tate

Installation view of 'Petrit Halilaj: Very volcanic over this green feather'

The exhibition was curated by Tate director Anne Barlow. She comments: 'Captivated by the power and presence of what he does. [This] significant new work is perhaps his most personal reflection on the trauma of the Kosovo war, shaped through the perspective of time.'

Indeed, as you journey through the gallery space, you are shifting and transitioning alongside Halilaj's memories. The most poignant image is that of a burnt house. It is engulfed in red and yellow flames on one side, and on the other, it is entirely charcoal black – depicting the aftermath of the fire.

Halilaj and his family didn't witness their house being burnt to the ground, though his drawing – entirely a figment of his imagination – is identical in appearance to the actual house. He tells Tate: 'I was impressed by how similar [the image] was [to reality]. Looking back after 20 years and analysing all of this, it was crazy to see how actually inside the drawings both the reality and the imaginations were present.'

© the artist. Image credit: Matt Greenwood, courtesy of Tate

Installation view of 'Petrit Halilaj: Very volcanic over this green feather'

Further along, you will see a little boy in an orange shirt crying, and directly behind him is a magnified exuberant peacock standing on a branch. Birds fly overhead, but a little further away there is a man dressed in combat holding up a rifle and a bloody knife.

The message Halilaj is trying to hammer home through his work is 'that art can be [a] meeting point. When two groups of people fail to see the same thing or see the opposite thing of the same story, it requires a long time to heal or to change the vision, and to bring new visions in a way that people see something new again.'

In 2020, Halilaj, alongside his partner and fellow artist Alvaro Urbano, produced work for Madrid's Palacio de Cristal. They transformed the glasshouse into a momentous bird nest. They dotted around enlarged yellow and red flowers that cast elegant shadows. The space was almost bare, allowing viewers to bask in the beauty of the bird's nest. Again, another immersive installation, but this time it was to relay the message of proud queer love, and identity.

© the artist. Image credit: courtesy of Tate St Ives

Petrit Halilaj at Palacio de Cristal

In 2017, 'Petrit Halilaj: RU' at New York's New Museum saw Halilaj recreate 505 Neolithic archaeological objects found before the Kosovo War in Runik, a village in Kosovo. He used the village he had grown up in as his launchpad. Like much of Halilaj's work, it paid homage to the beauty that his country has to offer. 'RU' consisted of large fabric sculptures that celebrated time and space.

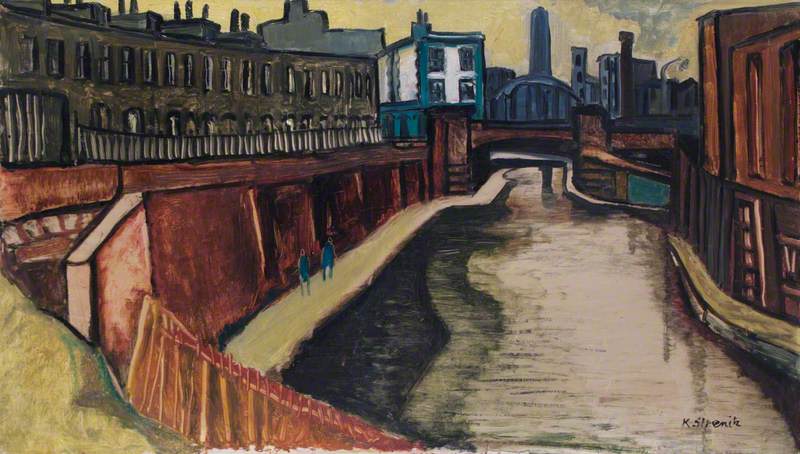

© the artist, courtesy of ChertLüdde, Berlin, Kamel Mennour, London / Paris. Image credit: Dario Lasagni

Installation view of 'Petrit Halilaj: RU' at the New Museum, New York, 2017

Fast forward to 2021, and 'Very volcanic over this green feather' can be seen as an expansion of the artist's skills when it comes to immersive art. Indeed, Halilaj's evolution is a thing to behold. His work clearly marks all that he is passionate about and all that he knows – heritage, identity and salvation. He is often looking to the future, as much as he is taking anecdotes from the past. Imagination is a poignant message within Halilaj's work – its possibilities and its limits.

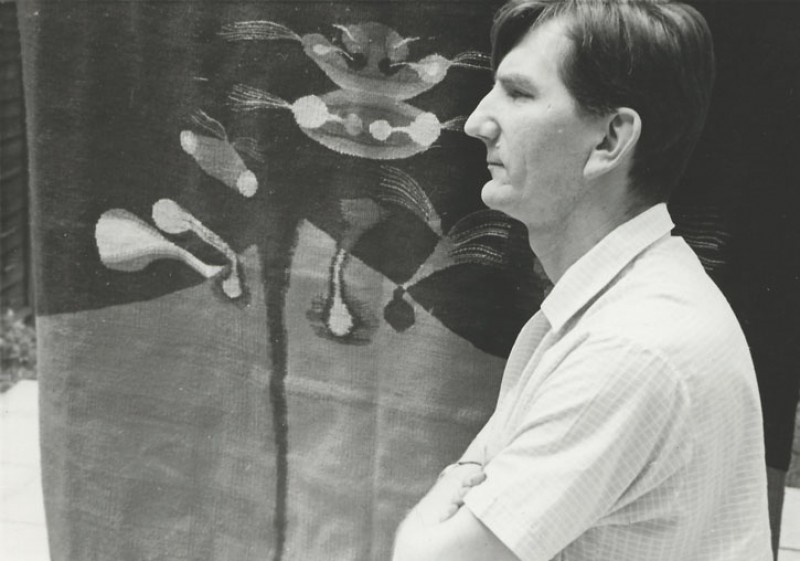

Image credit: Angela B. Suarez

Petrit Halilaj

Undoubtedly, Halilaj's work raises questions around identity, trauma and origins. He prompts his viewers to question where they come from, and how memories come to form our understanding of the world around us.

'I feel happier when I spend time like this,' Halilaj once said, by which he meant that he is content when weaving together narratives from the devastation of his past.

Siham Ali, freelance writer

'Very volcanic over this green feather' at Tate St Ives is open until 16th January 2022