In 2015, The Courtauld Gallery mounted a celebrated exhibition of Peter Lanyon's gliding paintings. The semi-abstract canvases were an impressive sight, expressing the sensations of unpowered flight seemingly effortlessly, even to those – like me – who have never been in a glider. Lanyon's endlessly inventive use of colour, shape and texture can sweep a viewer up on a journey in the way a good piece of music can. He makes it look easy. But really these works are the culmination of decades of effort and exploration, not of the skies, but of the land beneath.

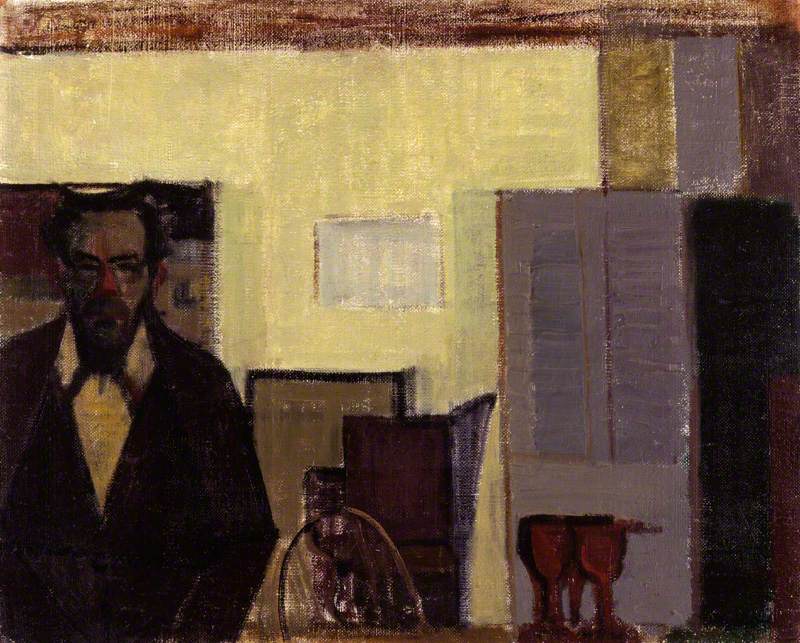

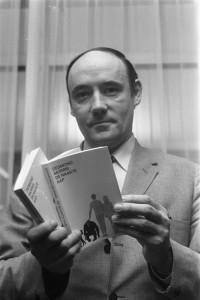

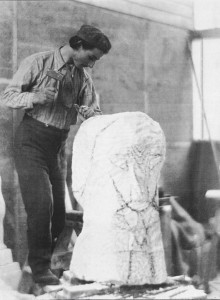

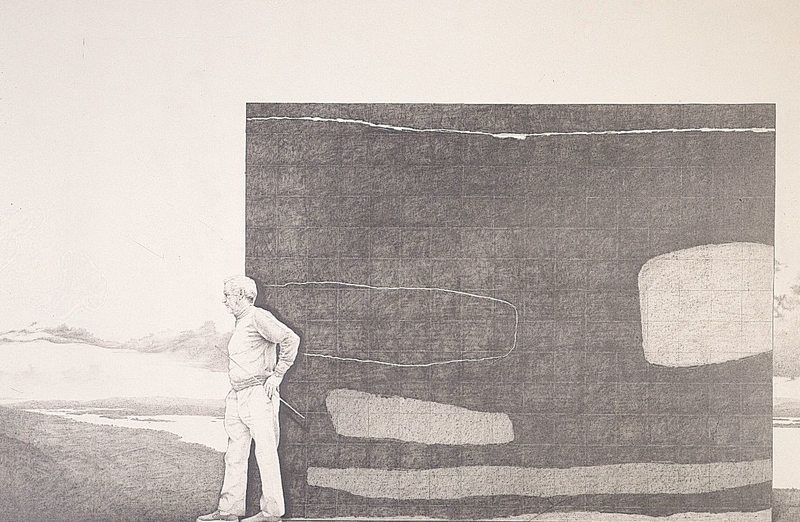

Peter Lanyon (1918–1964), in his studio at St Ives

1954, photograph by Gilbert Adams (1906–1996)

Lanyon's aerial expeditions often took him wheeling over Penwith, Cornwall's westernmost peninsular tip, whose ragged coastline shoulders its way into the Atlantic Ocean. It was his birthplace and lifelong home, and it underpinned his work, even – perhaps especially – when he was sailing high above it.

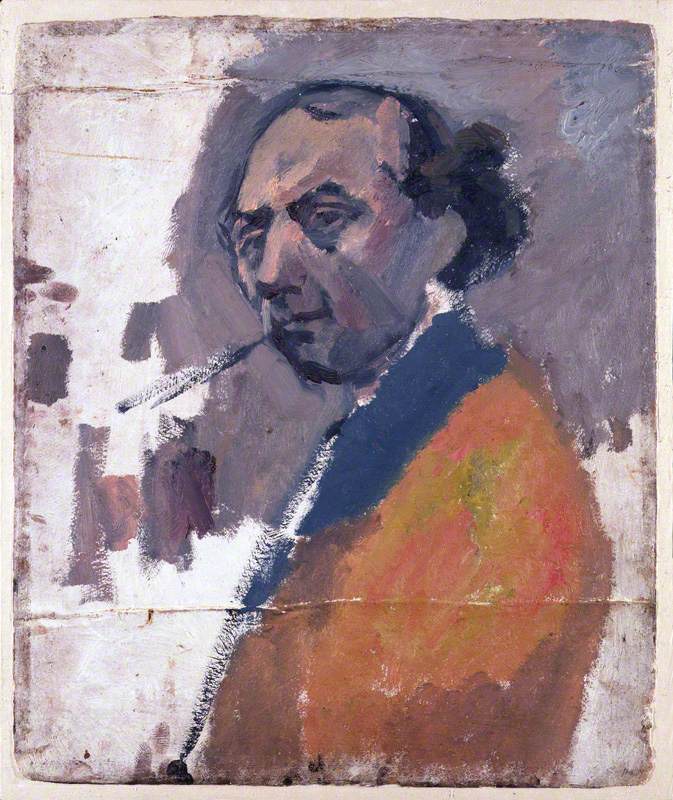

Lanyon was born in the fishing town of St Ives in 1918, to Herbert Lanyon and Lillian Priscilla Vivian. The family's roots were in the local mining industry, but his father was a keen amateur composer and pianist and Lanyon mixed in artistic circles from an early age. As a young painter he was taught by Borlase Smart, whose late-impressionist style initially rubbed off on him.

Orange and Blue Fishing Boat, painted in 1936 when Lanyon was still a teenager, depicts wooden vessels hauled onto a sandy beach. It's a jumble of colour, with masts, ropes and rigging loosely laid out in thick scribbles of paint. Already, Lanyon was testing the boundaries of representation and clearly enjoying the qualities of his chosen medium. 'I remember when I first saw a painting which was very thickly painted,' he later recalled. 'I was so excited with the quality of the thick paint that I went up and smelled it'.

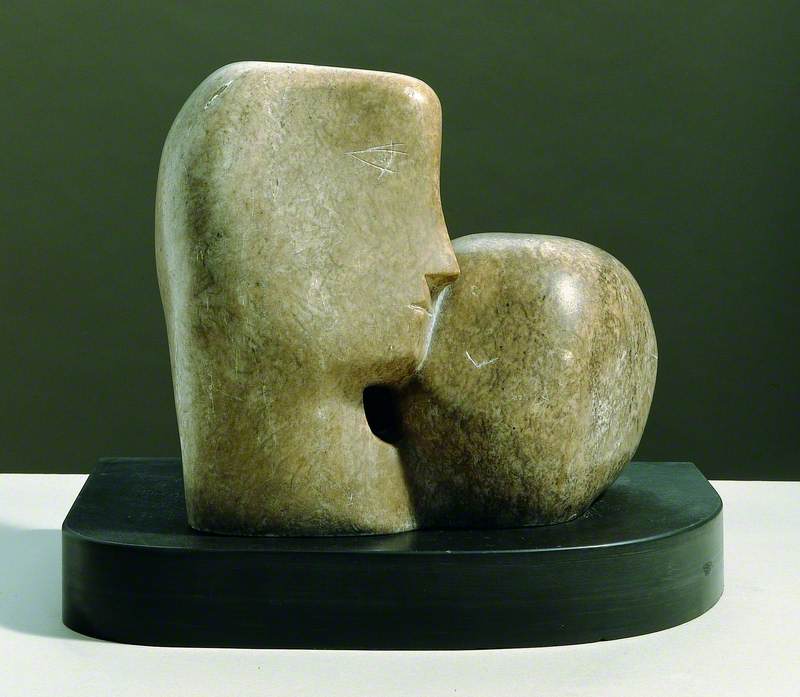

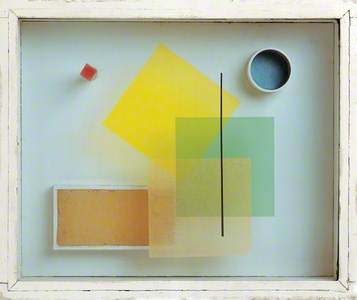

Lanyon studied at the Penzance School of Art, and in 1939 spent two months at the Euston Road School in London, which was famous for its modern brand of painterly realism. But he felt unhappy with his progress, perhaps sensing already that representational painting could never capture the full gamut of sensations, emotions and ideas he wanted to express. Luckily for him, the St Ives art scene was in the midst of a serious shake-up, as Naum Gabo, Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson – all progressive modernists – moved to the neighbourhood. By November 1939, Lanyon was taking instruction from Nicholson in abstract composition and the 'plastic values' (form, space, texture) believed to underpin art.

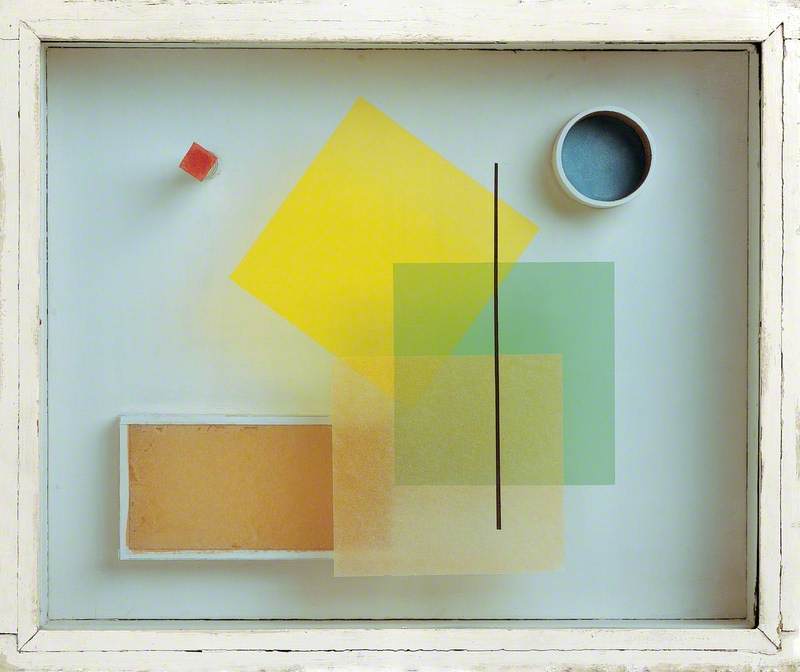

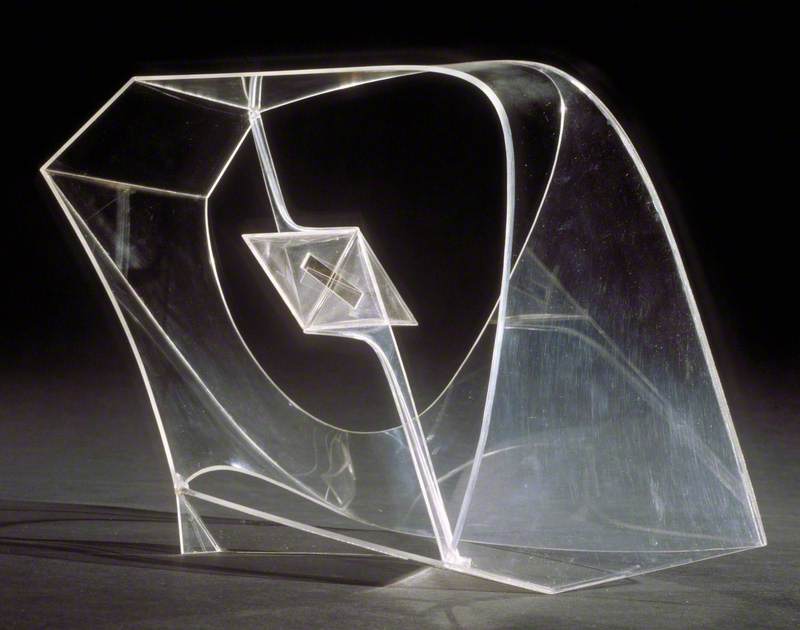

He also drew inspiration from Gabo, whose sculptures fascinated him. 'I'll never forget the first time I went to Gabo's house and saw a Perspex construction,' he once said. 'I don't think I had ever seen an object which was so obviously right in every way, and full of poetry'.

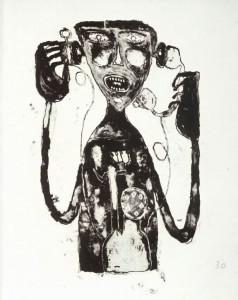

Lanyon took these new concepts and mulled them over during the war, making constructions while serving in the RAF as a flight mechanic. Few of his early sculptures survive, but one from 1947, now in the Tate collection, demonstrates how he adapted Gabo's spiralling structures to suit his own rough-and-ready style, adding splashes of colour to the assembled shapes. He continued to create these 'experiments in space' throughout his career.

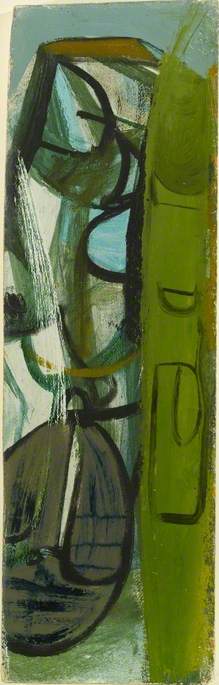

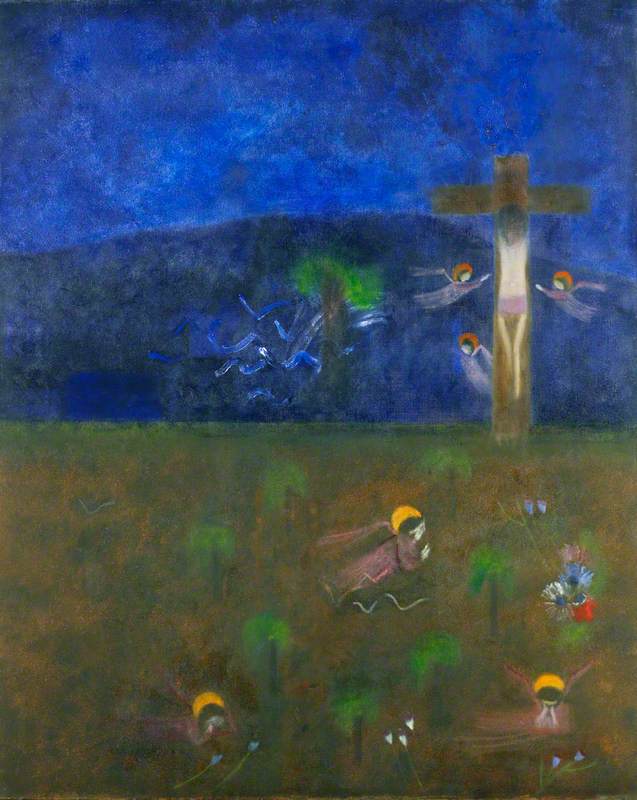

This new, confident sense of form and structure found its way into his paintings, such as The Yellow Runner (1946). Instead of presenting a single scene, here Lanyon collapses multiple views together. At the top of the image, a fox dashes across a hill; in the foreground, two horses loom large in profile; around them sweep encircling arms of yellow and dark brown paint which could represent an enclosure, or a cave, or the soil underfoot. Nicholson and Gabo had set him off down this semi-abstract path, but Lanyon was increasingly going his own way stylistically, and was beginning to imbue his paintings with deep personal symbolism. He described The Yellow Runner in rather cryptic terms as: 'a painting of a story. Runner with message on way to stockade horses. Fox as field. Reference to horses cut in hillside. Yellow Runner as fertilising agent. Stockade as womb. A homecoming'.

As well as depicting Cornwall (specifically, Gunwalloe near Helston), Lanyon was creating a symbol of security and fertility as he started his own family; he married Sheila Browne in April 1946, and they had their first child a year later.

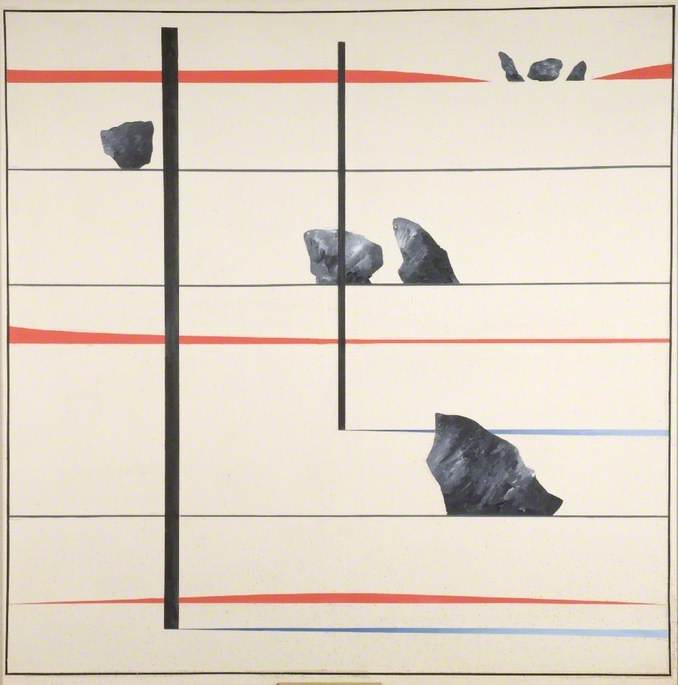

Realism had not been enough, and neither was pure abstraction. Lanyon wanted more, and over the years he embraced complexity wholeheartedly. He began to immerse himself in the Cornish landscape. He cycled through it, tramped across it, and was particularly interested in its hidden depths – sea caves and tin mines and other 'things under the soil'. He made notes and sketches, maps, models and constructions, and eventually he would try to set everything down in paint.

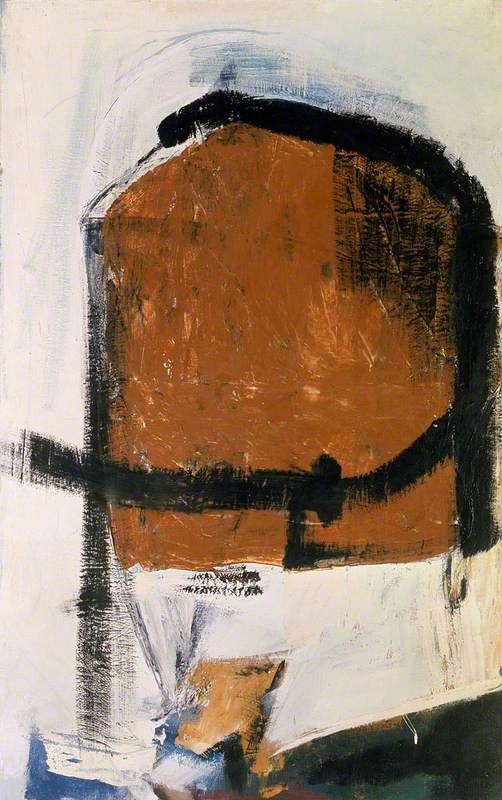

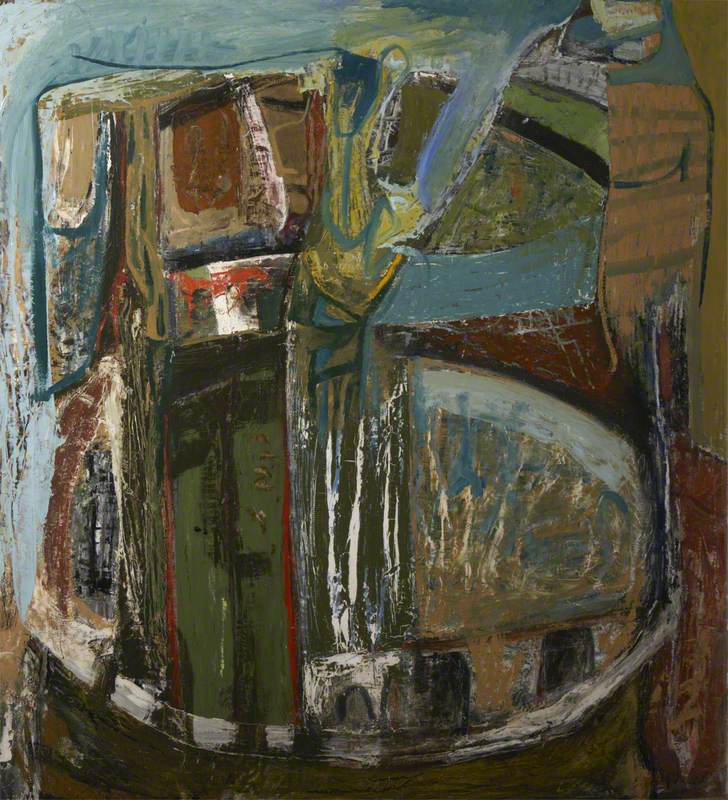

This was no easy task, and Lanyon's paintings are packed to bursting with overlapping, obscure imagery. Porthleven (1951), for example, features some key landmarks of the titular town, including its distinctive harbourside church, but Lanyon also embedded two large figures into the scene – a tall fisherman holding a lamp on the left, and a woman in a shawl on the right – who function as emblems of the community. Everything is painted in a medley of gestural marks that Lanyon felt expressed his physical sensations within the landscape. He worked on Porthleven for over a year, eventually wearing out the original canvas and repainting the final image on board in a matter of hours. He didn't mind the effort. '[I]t pays to struggle, revise, hit around and generally muddle up a thing like a painting or a poem,' he wrote to Roland Bowden shortly afterwards. 'The longer it can be delayed, the more concise the result – and the more intense!'

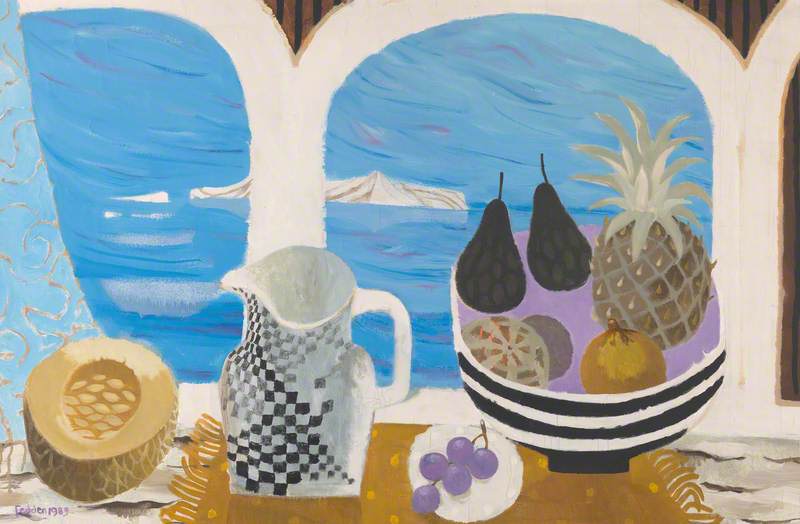

Lanyon's art was indebted to Cornwall – and as the St Ives art community expanded he emphasised his local roots to distinguish himself – but that didn't stop him finding inspiration in other places. He travelled frequently and adapted his style to fit the places he discovered. When painting Saracinesco in 1954, for example, he introduced rather more ochre and earthy reds along with repeated archway motifs to reflect the geology and architecture of the Italian hilltop town.

His pictures of Texas, made nearly a decade later when he took up a temporary teaching post in San Antonio, also have a distinctive character. In Texan Landscape (1963), warm reds and yellows dominate. The central rectangular shape suggests a highway, and the brushstrokes are accordingly smooth and expansive, suggesting speed and space. Lanyon first exhibited in the USA in 1954, and his paintings are often likened to those of the Abstract Expressionists. He hated pigeonholes, and rejected this one like all the others, but he admired and learned from their work, sharing their emotional understanding of colour and intense, sensual appreciation of paint.

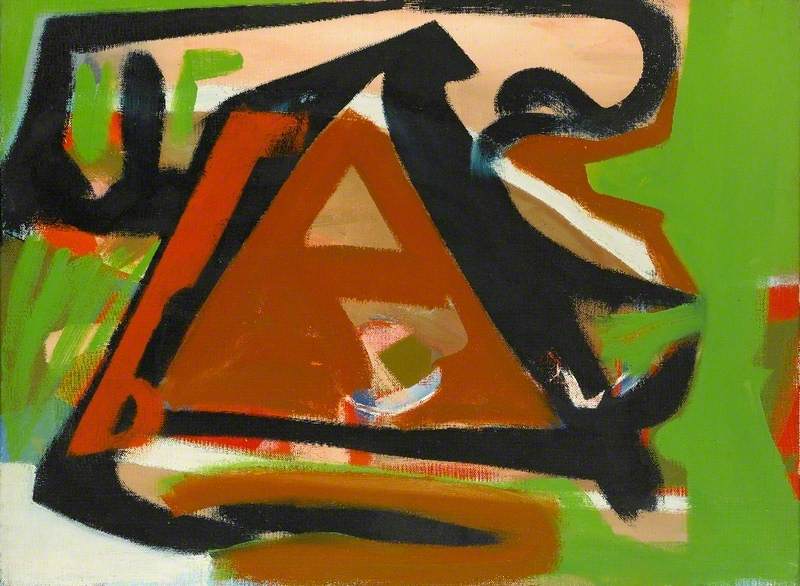

But the key influence in these years was surely gliding. Lanyon first took to the skies in 1959, and soon he was hooked. The sight of his beloved Penwith from above was revelatory, but gliding didn't just offer a new perspective on the landscape – it added a whole new dimension to it in the shape of the air itself. Suddenly he had to navigate the weather fronts sweeping in off the Atlantic, braving buffeting thermals and revelling in the clear air beyond. It was exhilarating, and the speed and motion suited his energetic style. He had always described his artistic process as arduous, like 'climbing the ventilation shaft of a mine'. Suddenly he seemed to have broken free. As he put it: 'One effect of gliding, of experiencing more and more in space, has been to lighten my paintings. They tended to be rather heavy. Sitting in the air, you are sitting in all dimensions.'

Glide Path (1964) demonstrates his point. Bright and airy, it features large swathes of pure colour, applied with rapid, confident strokes. The landscape is still there, but at a remove. In the top right, pale blue sections might represent the sea (or indeed, more sky), while a white area with a plunging vertical edge reads like a cliff. In the opposite corner, an expanse of grassy green is raked with dark shadows that could be from the glider, or are perhaps a sunken reference to the mines underfoot. In the centre is a flurry of white – a turbulent cloud, maybe – while all the way up the right-hand side the paint is slightly agitated, shaking up the view. Across it all cuts the glider itself, its rapid path denoted by two straight black lines. These are in fact two bits of plastic tubing, attached to the canvas to form a literal track across it, merging Lanyon's constructions and his compositions in a playful new way.

There's a sense in his gliding paintings of things coming together, perhaps best summed up by Lanyon's own note about North Cliff (1961; not on Art UK). He saw the work as describing 'A happening both in a historic sense; the effect of men on the county and in a moment of time... My interest in events both and the moment of experience and in ancient history as seen on the surface is beginning to be expressed to describe a mile of history within a gesture.'

Glide Path was to be one of Lanyon's final paintings. On 27th August 1964, he crashed on landing during a training session near Honiton, Devon, and died of unexpected complications four days later, aged 46. It is a tragic irony that gliding, which had set his work on such an exciting trajectory, should cut his life so short, and it's impossible not to wonder what heights his painting might have reached with a little more time to soar.

Maggie Gray, art historian and writer