Known for her unflinching, feminist depictions of modern women, the late Dame Paula Rego (1935–2022) might not have had too much in common with the somewhat obscure Renaissance artist Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495), who spent most of his career in the east of Italy painting religious altarpieces. But despite their dissimilarities, an exhibition at The National Gallery – 'Paula Rego: Crivelli's Garden' – will explore how Rego discovered, in Crivelli, something of an ally.

Crivelli's Garden

1990–1991, acrylic on canvas by Paula Figueiroa Rego (1935–2022). Presented by English Estates, 1991

When, in 1989, curator Colin Wiggins approached Paula Rego with an invitation to participate in a residency at The National Gallery, her response was curt: 'The National Gallery is a masculine collection and as a woman I can find nothing there that would be of interest to me.' Rego, then 55, was conscious of the lack of work by women on the Gallery's walls. Even today, in a collection of over 2,300 paintings, only 21 are by women. Nonetheless, a short while later, Rego phoned Wiggins back: 'The National Gallery is a masculine collection and as a woman I think I absolutely will be able to find things there for me.'

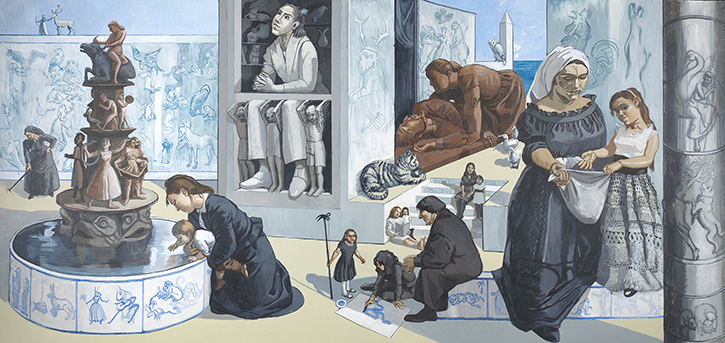

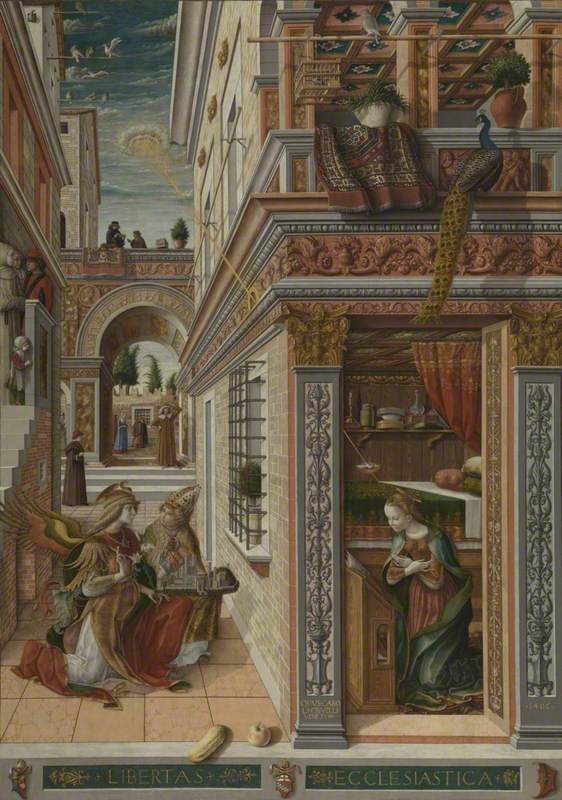

Rego was given studio space in The National Gallery for two years, beginning in January 1990. Part of her brief was to paint something for the restaurant in the new Sainsbury Wing. The result, Crivelli's Garden, her largest ever public commission, hung there for 30 years. In the process of painting its five constituent canvases, which have a combined length of over nine metres, Rego paid particular attention to an altarpiece by Carlo Crivelli, known as The Madonna of the Swallow. The exhibition will bring these paintings together again, shedding light on an extraordinary, transhistorical dialogue between the two artists.

La Madonna della Rondine (The Madonna of the Swallow)

after 1490

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495)

Although working at a large scale, Rego borrowed her composition from the small narrative panels at the foot of The Madonna of the Swallow – the part called the predella. Crivelli's predella contains scenes from four stories – the Nativity and the lives of saints Jerome, Sebastian and George – as well as an image of Saint Catherine of Alexandria. The panels are arranged horizontally and separated by vertical dividers, two of which are part of the wooden frame, and two of which are painted to give the illusion that they are.

Predella of La Madonna della Rondine (The Madonna of the Swallow)

after 1490

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495)

Comprising three large rectangular canvases separated by narrow, column-like strips, Rego's painting also represents religious stories within deep and busy perspectival spaces. Characteristically, her protagonists are women. The central panel shows a young girl, Judith, dropping the head of Assyrian general Holofernes into a piece of cloth held by an older maid. Immediately to the left of them, Delilah bends over Samson, having betrayed the Israelite leader by ordering his strength-giving hair to be cut off. Nearby, Mary Magdalene prays in a niche.

Crivelli's Garden II

1990–1991, acrylic on canvas by Paula Figueiroa Rego (1935–2022). Presented by English Estates, 1991

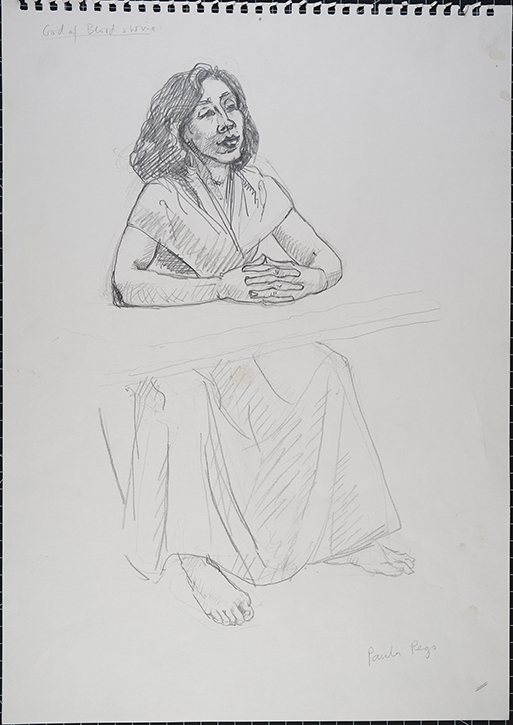

As well as looking at Crivelli, Rego also made several pencil studies of women who worked at the Gallery in preparation for her painting, some of which will be displayed in the exhibition. A sketch of the education department's Ailsa Bhattacharya sitting on the ground is a source for a similar figure in the second canvas of the painting. Mary Magdalene is based on a drawing of Lizzie Perrotte, who also worked in the education department.

Study for 'Crivelli's Garden'

1990–1991, pencil on paper by Paula Figueiroa Rego (1935–2022)

The Gallery employed these women to expound on the achievements of long-dead men. Inserting them into her Crivelli-like narrative space, Rego gave them new roles within, rather than next to, the frame. In a way, this mirrors Rego's decision to borrow her composition from Crivelli's predella rather than the larger image of the enthroned Virgin and Child. What was once marginal now takes centre stage.

Study for 'Crivelli's Garden', Mary Magdalene

1990–1991, pencil on paper by Paula Figueiroa Rego (1935–2022)

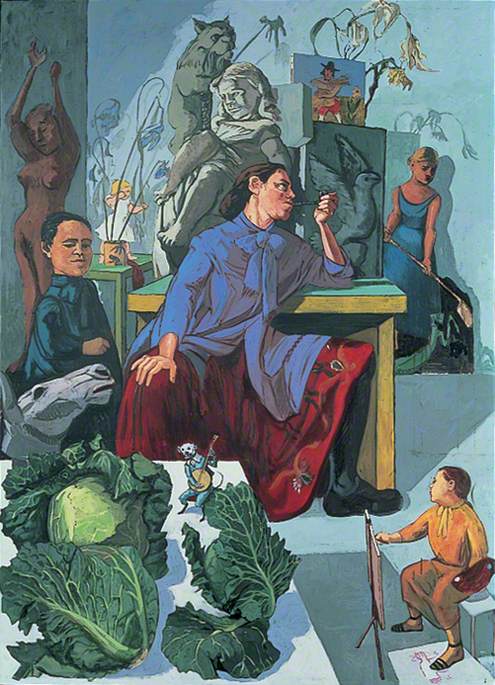

However, Rego was aware of the limitations of straightforwardly recasting women in roles once occupied by men. The 1993 painting The Artist in Her Studio, which almost certainly developed out of the work she made at the Gallery, satirises such an approach to art history. In it, the pipe-smoking painter bears over her timid assistants with as much hauteur as any pompous old man: hardly a radical revision of what a great artist looks like.

With Crivelli's Garden, Rego questions the gendered assumptions by which an artist qualifies for greatness at all. Crivelli has a lot to say on that matter. His relationship to art history demonstrates how the stories we tell about art prioritise certain kinds of artists over others.

Born in Venice around 1435, the painter produced most of his work in the Italian Marche region in the latter half of the fifteenth century, at a remove from the urban centres of the Renaissance such as Venice, Florence or Rome. For all their apparent weirdness, his altarpieces proved delightful to the Inquisition-era clergy who commissioned most of them, and his work fetched higher prices than most of his now better-known Florentine contemporaries, such as Botticelli.

However, his reputation suffered after his death, partly because he wasn't included in the narrative of artistic progress described by Giorgio Vasari in his hugely influential 1568 book The Lives of the Artists. Even if Vasari had heard of him, Crivelli would have proved awkward to fit into the story of the revival of naturalism that began with Giotto and reached its peak with Michelangelo. As it happened, Vasari's story set the pattern for future art historians, and from then on Crivelli's art was deemed too Gothic: other Italian artists of his era looked more toward the styles of antiquity.

Saint Mary Magdalene

probably about 1491-4

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495)

This is not to say Crivelli hasn't had his admirers. But even the most ardent have struggled to fit him into the history of art. In the introduction to his 1953 book The Italian Painters of the Renaissance, historian, collector and connoisseur Bernard Berenson wrote: 'a formula that would, without distorting our entire view of Italian art in the fifteenth century, do full justice to such a painter as Carlo Crivelli, does not exist'.

Crivelli's antagonism to the traditional narrative of art history might have appealed to Rego. Women, like Crivelli, had also been marginalised in a story of men whose seminal works could compare with – sometimes even surpass – the prodigious artists of the ancient world. This story left little room for the women who, as a result of societal expectations, had far fewer opportunities to practise art professionally, and, when they did, often had their work dismissed as 'feminine'. It also pushed aside an artist like Crivelli, whose geographic marginality, visual maximalism, profuse ornamentation and faulty Latin cast him as a provincial figure.

The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius

1486

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495)

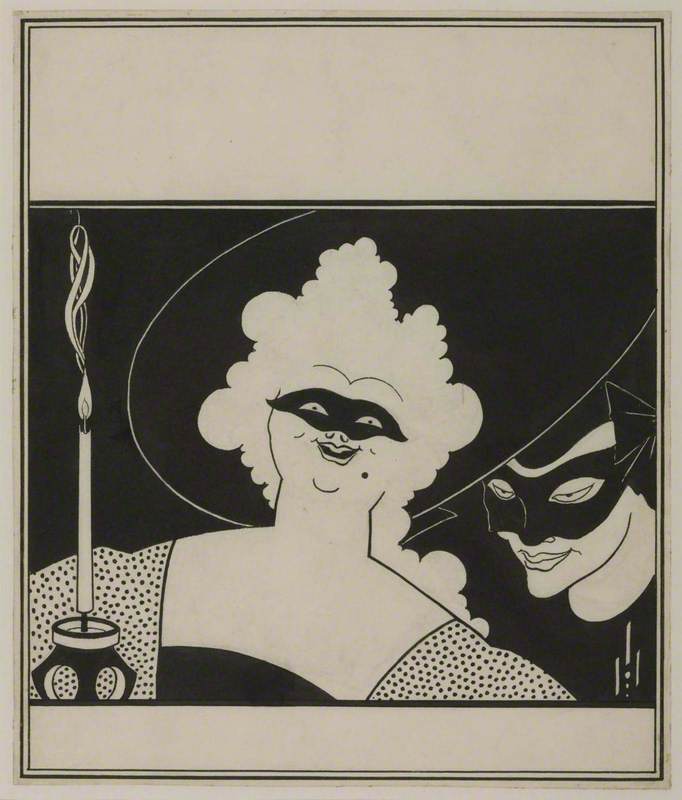

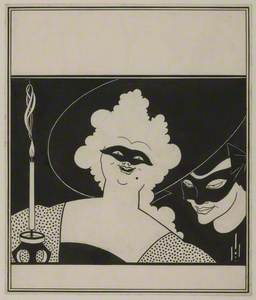

Lurking in Crivelli's historiography is also the suspicion that his art lacked masculinity. In her well-known 1964 essay 'Notes on Camp', Susan Sontag used Crivelli as one of her examples: 'The hallmark of Camp is the spirit of extravagance. Camp is a woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers. Camp is the paintings of Carlo Crivelli, with their real jewels and trompe-l'oeil insects and cracks in the masonry'.

Defining Crivelli as camp (her other examples include Aubrey Beardsley and Oscar Wilde), Sontag implicitly separated him from the 'seriousness and dignity' that she associated with 'the pantheon of high culture', such as Dante's Divine Comedy or the paintings of Rembrandt.

The perception that he was unmasculine might have endeared Crivelli to Rego. That said, Rego showed little interest in the art-historical details when Colin Wiggins showed her around the Gallery. More likely, Rego's experienced eye discerned something in Crivelli's paintings that set them apart from the others in the collection, intuiting his singularity directly, without having to pore over the books. This was, I'd suggest, the presence of a distinctive spirit of contrariness within his work, a Cheshire-cat kind of mischief, which Rego took and made her own.

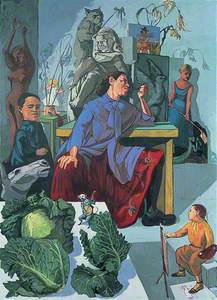

See, for example, the odd disparities in scale between the figures in Crivelli's Garden. Wiggins noticed them too. In a transcript of a conversation between Wiggins and Rego in the Gallery archives, Wiggins asked: 'Looking at your Crivelli's Garden, the scale in that is all very quirky, isn't it? Because those saints aren't real saints, they are all sculptures in Crivelli's Garden, aren't they?' Rego confirmed: 'They're all sculptures in Crivelli's Garden you are absolutely right. It's all made up, none of it's real… except, of course, it's all real.'

Crivelli's Garden III

1990–1991, acrylic on canvas by Paula Figueiroa Rego (1935–2022). Presented by English Estates, 1991

This interplay between what is and isn't 'real' lies at the heart of the painting. While some figures, such as Samson and Delilah, seem quite clearly to represent bronze casts, others are ambiguous. How can we make sense, for example, of the figure to the left of the right-hand panel who looks like a bronze, but whispers to a girl who looks very much alive? And how can we categorise the tiny boy standing next to them? Is he more or less 'real' than the figures in the picture that he stands next to?

With devices like these, Crivelli's Garden puts us on our guard. If we cannot distinguish, within its fictional space, between images and living people, how can we trust anything it shows us? Rather than showing the world as it is, the picture seems to reveal what it means to make an image.

Crivelli's Garden IV

1990–1991, acrylic on canvas by Paula Figueiroa Rego (1935–2022). Presented by English Estates, 1991

Five hundred years earlier, Crivelli did something similar. In The Madonna of the Swallow, there is a frieze beneath the Virgin Mary's feet where you might expect to find sculptural reliefs of natural forms, such as those carved into the wooden frieze and pilasters of the painting's elaborate frame. Instead, there is what looks like real fruit. Saint Sebastian's halo, surely an immaterial and otherworldly thing, looks like a golden frisbee. It even casts a shadow. And what about, completely out of proportion, the giant cucumber dangling near the Virgin's head? Surely this implies that the image before us cannot be taken, at face value, as a truthful representation of Heaven. Does it not, amongst other things, emphasise what we see is fiction?

La Madonna della Rondine (The Madonna of the Swallow)

after 1490

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495)

Many artists have played games of illusion, but none with the intensity of Crivelli. In almost every detail, the Madonna of the Swallow accosts you with its artificiality. (Perhaps this was useful in a culture worried that people might worship an image instead of the divinity it pointed towards.)

Questioning the truthfulness of what they represent, Crivelli and Rego seem to paint their figures at a slight remove, as if putting them in quotation marks. To modern eyes, this feels like a form of irony, antithetical to the bombast of the artist who seeks to assert themselves within the grand narrative of art history (as Rego satirises in The Artist in Her Studio). For complex yet overlapping reasons, neither Rego nor Crivelli could be a part of that.

Their attitude is in marked contrast to the 'seriousness and dignity' of much of The National Gallery's collection, which tends to strive towards truth to nature or an ideal of beauty. Instead, Crivelli's Garden – and Crivelli – show that whatever else a picture is, it is also a lie.

Rego, when she saw it next to others in the collection, felt a pang of anxiety: 'The moment I remember most clearly is when they came to take it out of my studio. They wheeled it through The National Gallery, and I was embarrassed and terrified. It wasn't the public seeing it I minded, it was the pictures. I apologised to each picture we passed... But I'm proud of it now.'

Henry Tudor Pole, writer and art historian

With thanks to Priyesh Mistry, curator of 'Paula Rego: Crivelli's Garden', showing at The National Gallery, London from 20th July to 29th October 2023

Further reading

Fiona Bradley, Paula Rego, Tate Publishing, 2002

Minna Moore Ede, 'Recasting the Establishment' in Elena Crippa (ed.), Paula Rego, exhibition catalogue, Tate Publishing, 2021