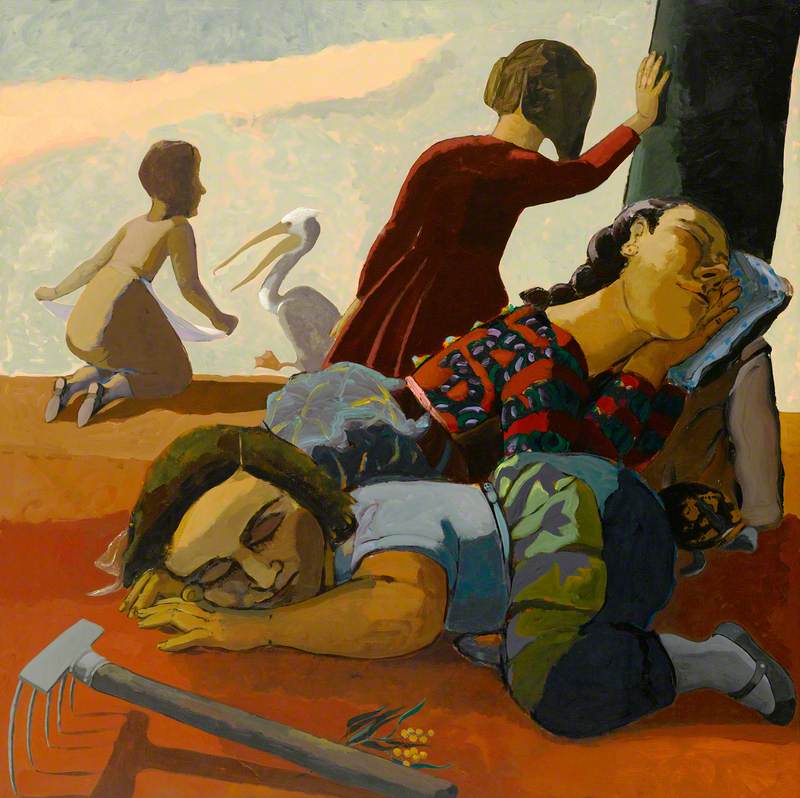

Something terrifying, unfathomable, has happened to Paula Rego's 'Dog Women': they cower, bay, simper, snarl. In broadcasting base emotion with such ferocity, their behaviour betrays established etiquette. They are unsettling because they communicate some deeply rooted, horrifying darkness that we recognise within ourselves: terrible pain, grief, longing and humiliation.

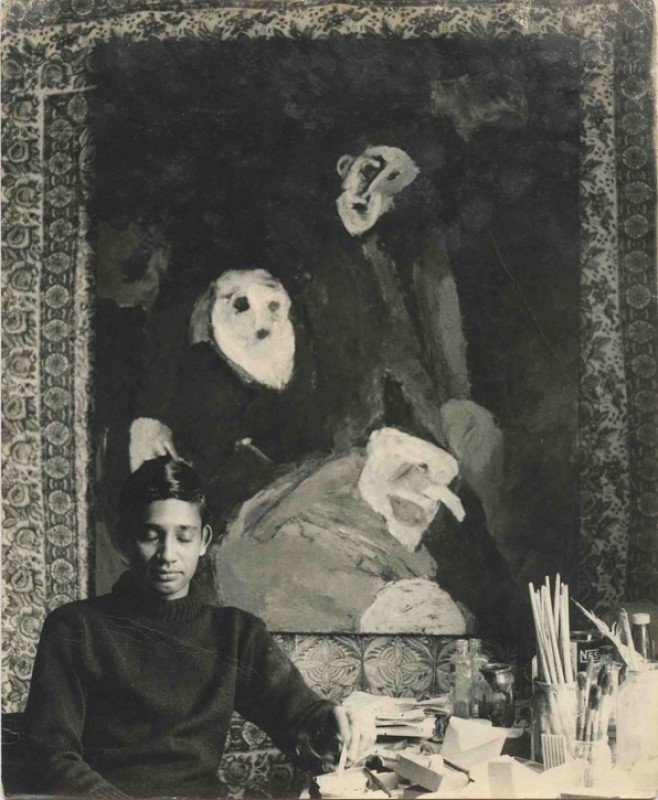

Rego painted her Dog Women in the early 1990s, a few years after the death of her husband, the artist Victor Willing. Rego and Willing had met at the Slade School of Art in the 1950s. Rego, not yet 20, had been sent by her father to study in London.

Portugal was then under the Salazar regime, and Rego recalls an oppressive upbringing, both politically and socially. The cowering obedience of the Dog Women was learned here: under the forces of a dictatorship and a society that demanded compliant behaviour of its women.

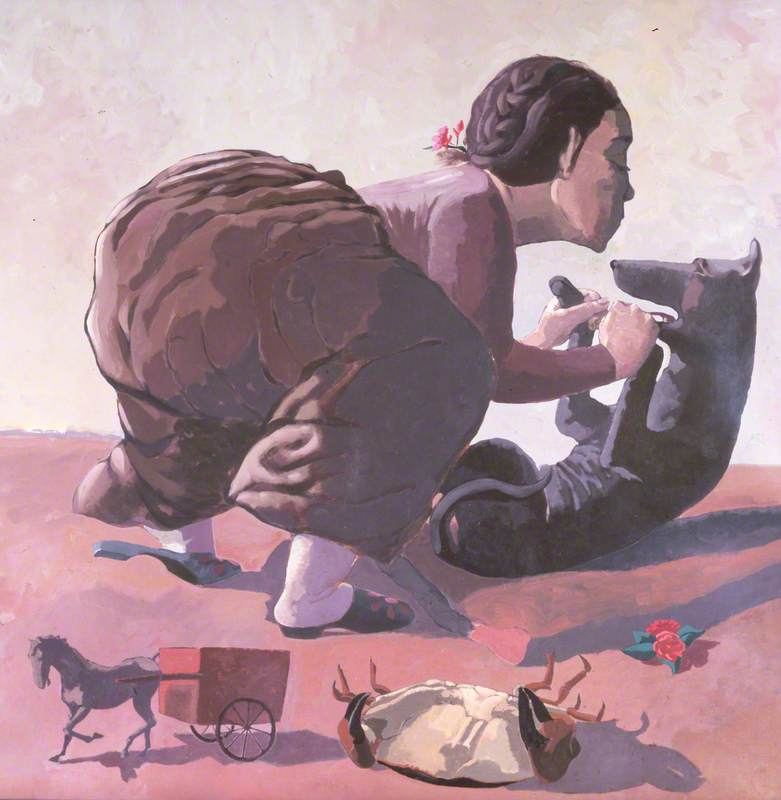

One of the Dog Women appears curled up sleeping on their owner's coat; another is another being kicked out of bed for soiling it; The Bride lies back submissively baring her belly for approval.

'They were what I felt' Rego has said. As Willing became more ill, Rego took on a Portuguese au pair Lila Nunes to assist her in caring for him and the family. Nunes soon took on a different role, working with Rego as a patient and mutable model.

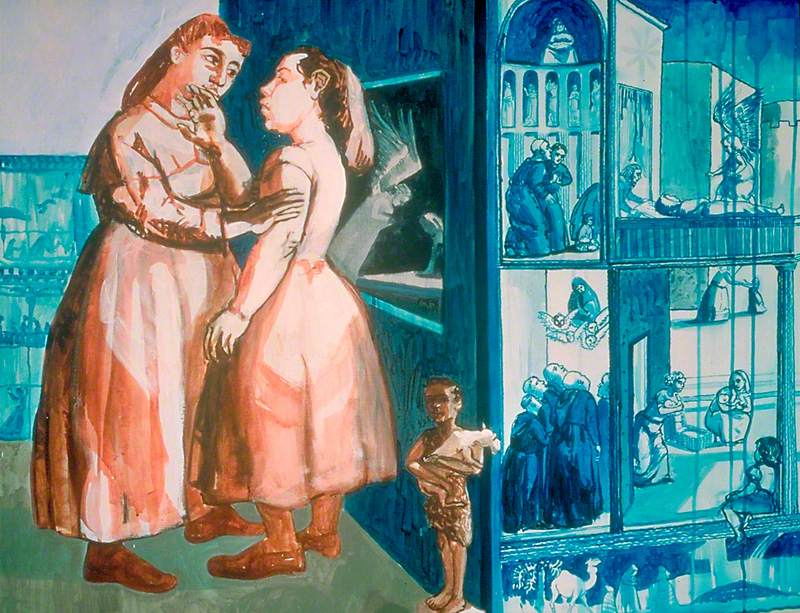

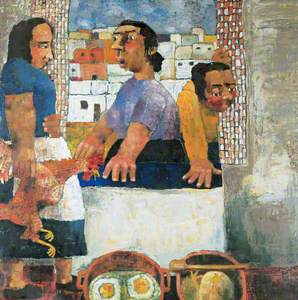

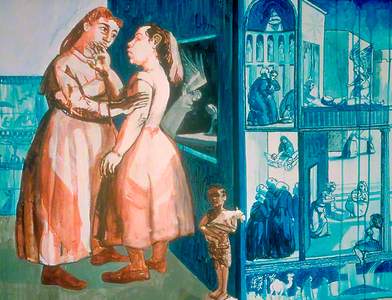

In 1986 and 1987, Nunes posed for a series of paintings (among them Snare and Untitled 'Girl and Dog' Series) of sturdy, forceful girls tending to floppy, helpless dogs: dressing and undressing them, shaving and feeding them. The dog seems helpless within the girls' grasp, sometimes they submit, sometimes they struggle, but they are always ultimately overpowered.

Bringing together symbolism relating to matriarchy (the mother, grandmother and child), romantic love, and the circularity of life, Rego commenced The Dance (1988) at Willing's suggestion. It was to be the unifying work in an exhibition of her paintings at the Serpentine Gallery, and featured figures based on Rego herself (the standing figure to the left), her husband and son. Willing died before the painting was completed.

Informed by the unflinching emotional honesty that she pours into her work, Rego's paintings and drawings resist neat, comfortable interpretation according to any reductive, compartmentalised understanding of human feeling. They broadcast an inner world that is emotionally messy and vexed with contradictions. Love and resentment, nurture and violence, fear and desire, grief and fury: all these things can coexist, and do, in her work.

Speaking of her devastating Abortion series (1999), Rego has said that physical pain and the erotic are tied inseparably together: the women are contorted into positions where they are available to be penetrated either by the abortionist's hand or by a lover. Informed by her own experience of backstreet abortions in 1950s London, these ten large-scale pastel works were conceived as a forceful riposte to Portugal's cruel anti-abortion laws, and openly broadcast human experience that was at that point otherwise invisible, within the world of art and beyond it.

While drawing on her own life experience, Rego prizes stories ancient and modern for their powerful ability to externalise deeply felt things, to give narrative body to the otherwise inexpressible.

She has delved into the fairy tales, myths and nursery rhymes of Britain and Portugal. The casual violence and magical thinking that seem commonplace in the stories and songs that we have grown up with are given human weight again in her pictures.

We find Snow White after eating the poisoned apple contorted in agony, tearing at her clothes and tumbled upside down by devastating pain. No hint of Disney sanitisation here: this Snow White has solid form and experiences the physical suffering that comes with it. Disney princesses don't puke: this one looks like she might.

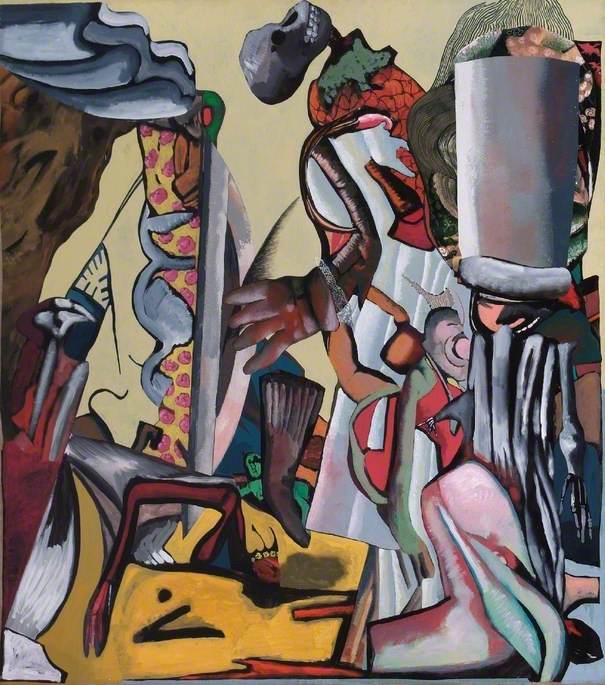

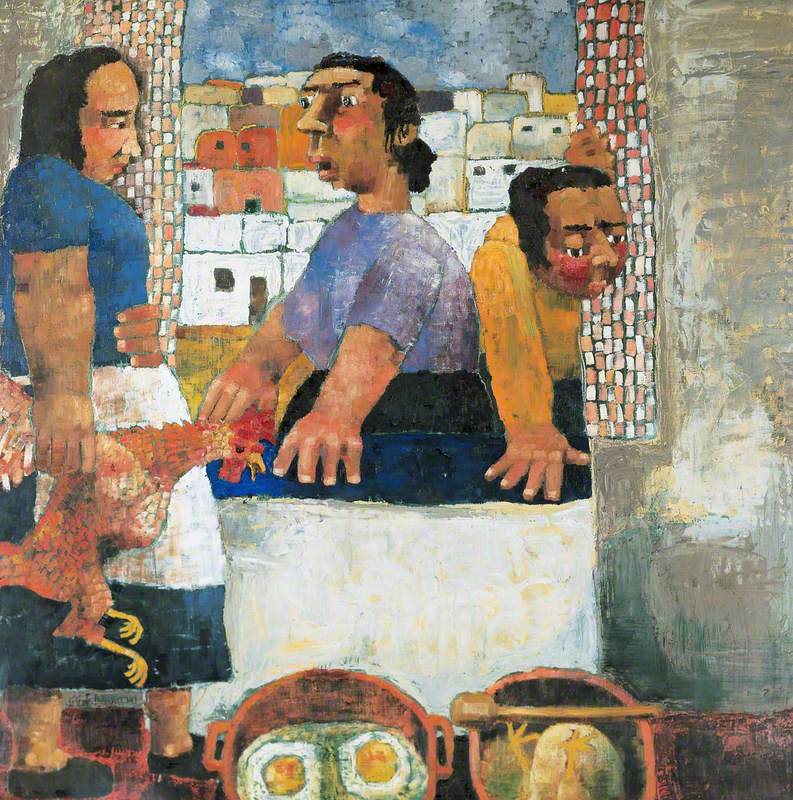

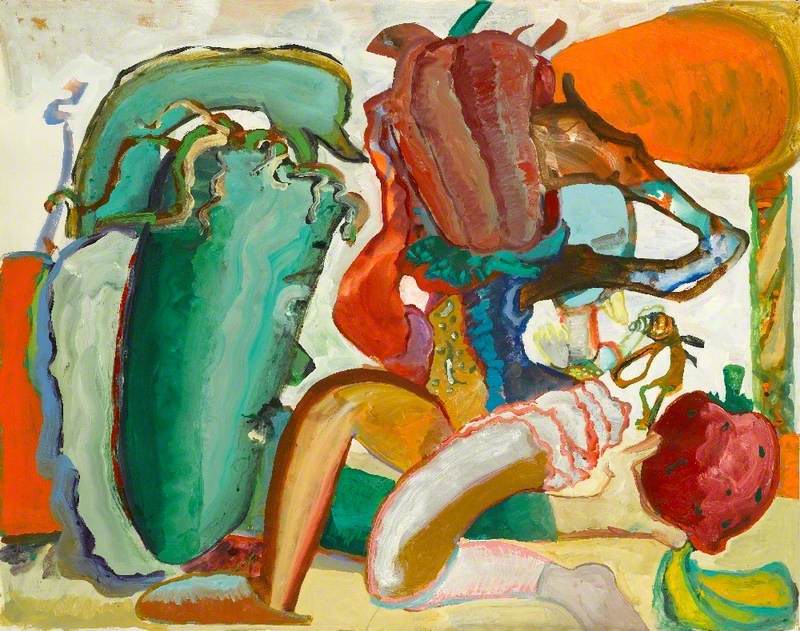

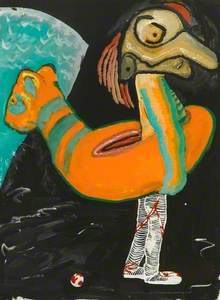

In the early 1980s, Rego produced loosely painted works on paper in which a cast of stock characters – a bear, a monkey, a wife, a dog among them – engage in acts of appalling cruelty and subterfuge, among them Minotaur Slicing Goat, Wife Cuts Off Red Monkey's Tail, and Chicken Persuading Woman.

'I always know the people in my pictures. Very often they take the form of monkeys and bears and all sorts of things. It's easier if you make them into animals because you can do things to animals that you can't do to people because it's too shocking,' Rego has explained, 'I used animals, because I could do all kinds of nasty things and get away with it.'

A set of etchings linked to British nursery rhymes that Rego produced in 1989 re-casts the creature protagonists at human scale: Baa, Baa, Black Sheep is a handsome if lascivious figure, clutching rather insistently at his little shepherdess.

A Frog He Would A-Wooing Go looks like a fat old bore in a cricketing sweater, hanging out round the back of a pavilion with low-life rodents. Little Miss Muffet's spider is terrifying: a giant man-faced arachnid, rearing up and lunging for the little heroine with javelin-like legs.

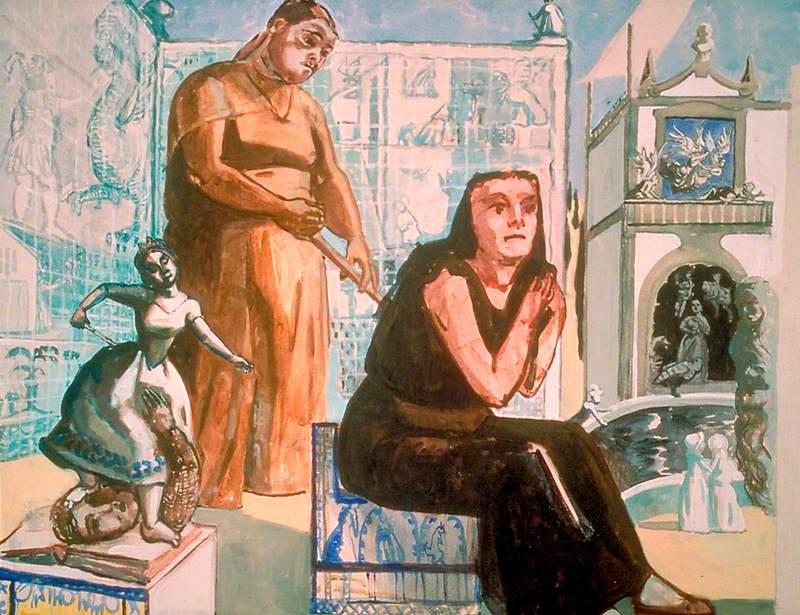

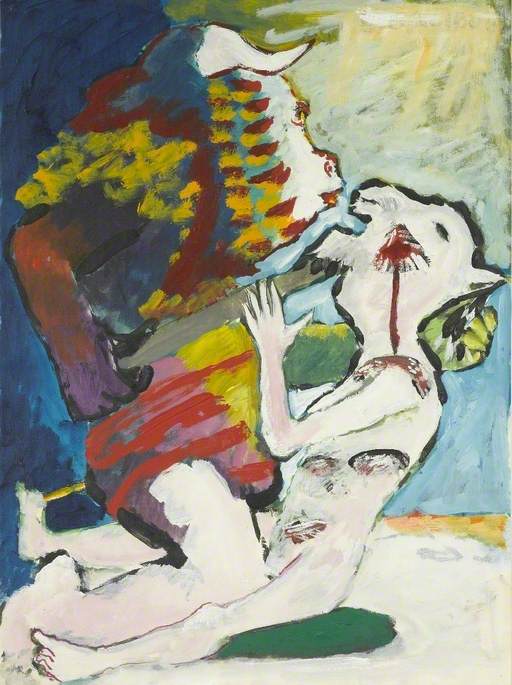

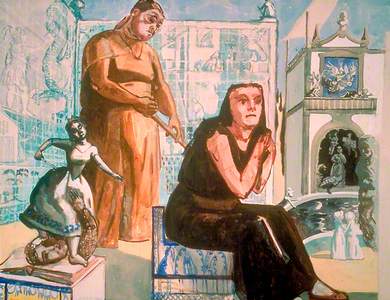

Rego's series, inspired by Eca de Queiroz's controversial novel The Sin of Father Amaro (1875), suggests appalling acts committed in the name of ease, self-love, pride, guilt and propriety. Human weakness and human ruthlessness become two sides of the same coin. We see the titular priest cossetted by the women around him. He seems a passive and floppy figure amidst bold and muscular female forms crowding in from every side of the pictures, yet his weakness is lethal.

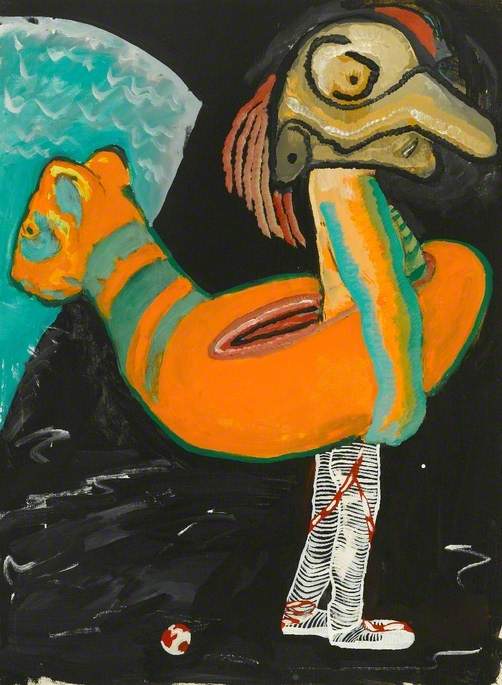

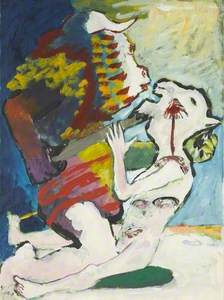

Angel

1998, pastel on paper mounted on aluminium by Paula Rego (b.1935). Private collection. Featured in 'Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance' at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art

The final work in the series is the avenging Angel (1998) – a fearsome woman, radiant and powerful in a full golden skirt and stiff black bodice, brandishing sword and sponge, ready to restore justice, brutally, if need be.

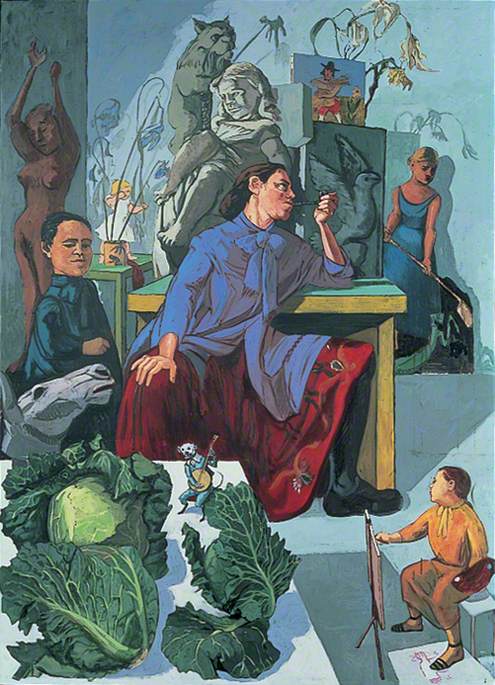

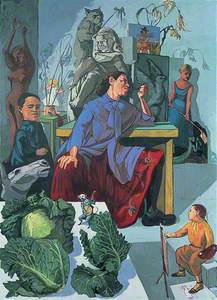

There is humour to Rego too, and mischief. With irresistible tongue in cheek, The Artist in Her Studio (1994) plays with romantic conventions of the lone artist genius – male, contemplative, wedded to his work.

Here, Nunes-as-Rego sits centre studio, legs splayed and skirts hitched to display sturdy footwear as she smokes a pipe while sitting for her own portrait. This artist is a sculptor. While she is not Rego, her the studio abounds with objects and figures familiar from Rego's work: cabbages tumble across the table like the one that stood in for the head of her mother in an early painting, and the crinkly leaves of which lend their form to Portuguese crockery. There are bipedal cats and mice from her beastly stories, a forceful looking maid, and a fairy tale Cinderella sweeping behind them.

This is an artist at the centre of their universe, where imagination meets technical virtuosity. It is an assertion of power.

Hettie Judah, senior arts journalist

A version of this essay first appeared in Numéro Art 3, published 15th November 2018.

The exhibition 'Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance' is open at the National Galleries of Scotland until 19th April 2020.

Further reading and watching

Watch clips from the 2017 documentary Paula Rego: Secrets and Stories on the BBC website

Interview with Paula Rego, The White Review, January 2011