Chantal Joffe has already been working in her studio for an hour or so when she answers the phone to me at 10am. Since the birth of her daughter Esme, Joffe explains that she's 'been strict about making art during school hours'.

All artists and writers know the importance of protecting creative time; Joffe tells me that Susan Sontag had a Post-it Note stuck to her fridge which read, simply, 'No'.

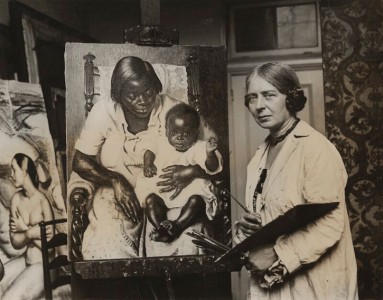

Chantal Joffe at Arnolfini

2020, photograph by Lisa Whiting

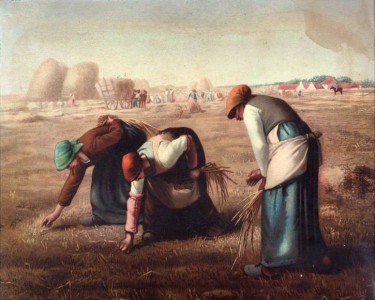

However, Joffe also acknowledges the need for space away from her studio. A lover of city life, she will visit exhibitions and art museums, watch people, and wander around London, where she lives. Joffe has most recently been to see 'Artemisia' at The National Gallery. It's the first major exhibition of Artemisia Gentileschi's work in the UK, featuring dramatic narratives of historical and Biblical heroines, as well as self-portraits.

'It feels so exciting to see paintings – I've missed it more than I can believe,' Joffe reflects. 'It's an extraordinary show but it's also one that has also made me angry – she's been edited out of art history.'

Included in the exhibition is Gentileschi's Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (c.1638–1639, Royal Collection Trust), which Joffe picks out: 'here she's painting herself into art history. As a woman it really is incredible. It makes you believe.'

Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting

1638–1639, oil on canvas, by Artemisia Gentileschi (1596–1653 or after)

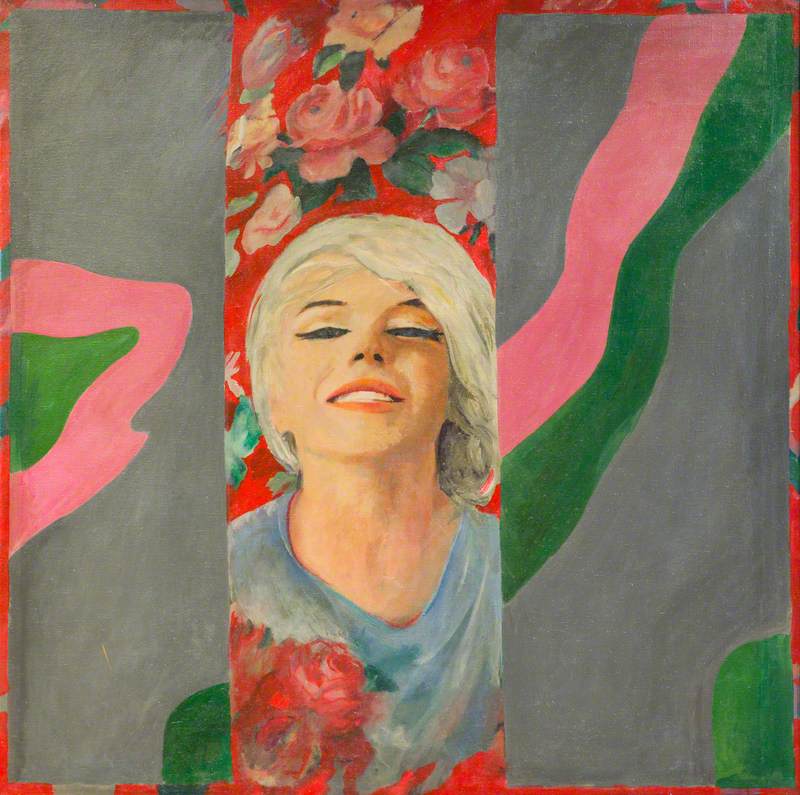

Women are a recurring subject for Joffe, who is best known for her large-scale, psychologically charged paintings of the female figure. Pulling the paint around the canvas in broad brushstrokes, Joffe depicts women in a distinctively understated, yet powerful, manner. They echo the expressive portraits of women and girls by Paula Modersohn-Becker – an artist Joffe admires.

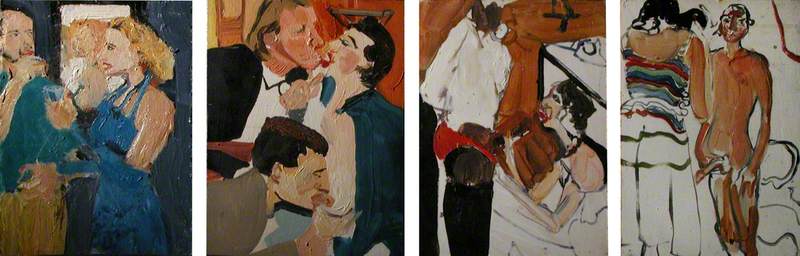

Often Joffe's models are those closest to her, although this hasn't always been the case. The artist spent four years at Glasgow School of Art, from 1988 to 1991, where she learned to paint from the figure during life drawing classes. However, when she arrived at the Royal College of Art in 1992 her practice shifted; she began to work, instead, from pornographic material.

'How and why did this come about?' I ask.

'What I wanted to paint was people having sex, but not as pornography. There was a desire to paint things unpaintable, at that time.'

Joffe needed imagery to work from, and reminds me that 'this was the pre-internet age'. She recalls a tutor, with whom she is still good friends today, taking her to Soho to buy pornography. 'I remember the day clearly, and afterwards we visited a Picasso show at Tate – it took courage for him to take me to buy porn. With this imagery, I could move forwards for the next five years.'

In these early paintings, Joffe explains that she intended to offer a rebuttal to the fast-paced sex scenes of Hollywood films and TV shows which, as she points out, 'accelerate quickly'. Instead, she 'wanted to slow sex down and turn it into little stories'. She also painted herself into works, such as Untitled (Face) from 1994.

'Why?' I venture.

'At this point in my life, I was interested in sex and exploring what sex means. I was trying to fit myself into these sex scenes.'

For Joffe, making art is personal: 'my paintings are a mash-up of everything that is preoccupying me at that time.'

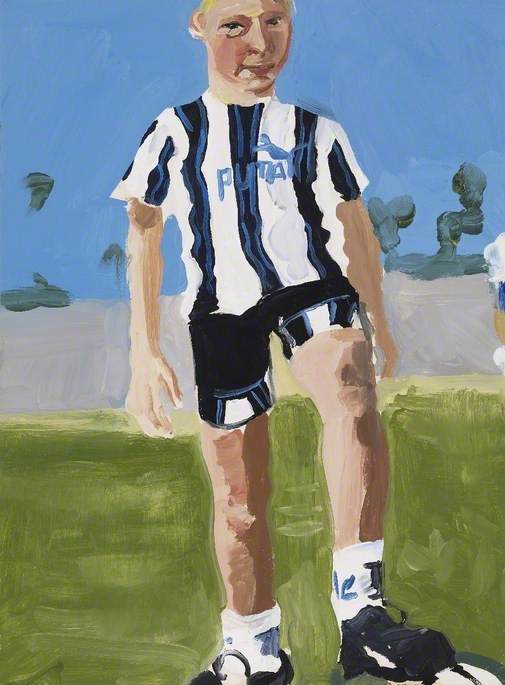

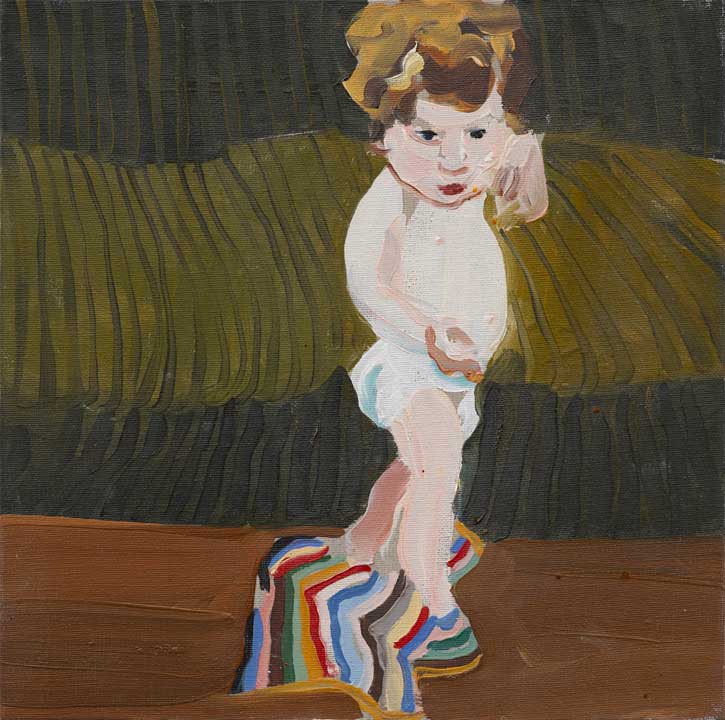

Many of the artist's early paintings also feature small children.

'Who are they?' I ask.

'These were children featured in mail-order catalogues. I was working out 'what is painting', and making very small, precise paintings with pure colour; I was also interested in re-animating images from catalogues, and making these children real again. I was wanting to have children – there are also endless paintings of babies from that period.'

Esme with a Striped Blanket

2008, oil on canvas by Chantal Joffe (b.1969)

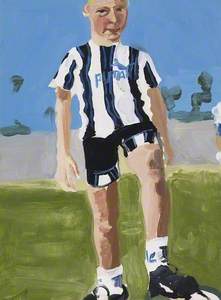

In 2004 Joffe's daughter, Esme, was born. Since being a toddler, she has been the subject of many paintings, such as Esme by the Railings (2014), in which she stands insouciantly in an urban landscape. There's an increased intimacy to these unstaged works, which are indicative of the close emotional connection between Joffe and her daughter.

Esme, now aged 16, is the subject of Joffe's current solo show at Bristol's Arnolfini: 'For Esme – with Love and Squalor'. The exhibition charts their relationship, including the act of care and being cared for, between mother and daughter.

The show's title, taken from a short story by J. D. Salinger, also reveals the significant role that books play in Joffe's painting practice. Joffe reflects on the intersection between art and literature:

'Books change the way we see the world and painting does that too. They have the power to take you somewhere else. Reading leads to painting. I love reading biographies: they allow you to imagine life close enough – you can paint that. Literally, I will paint poets that I love.'

Esme at Sixteen

2020, oil on board by Chantal Joffe (b.1969)

Particularly inspired by women authors, Joffe has paid homage to the likes of Anne Sexton, Elizabeth Bishop, Sylvia Plath and Olivia Laing, by painting their portraits. Similarly, Esme loves to read and paint, and has just painted her mother a portrait of Emily Dickinson for her upcoming birthday.

Me and Esme in the Garden

2020, oil on canvas by Chantal Joffe (b.1969)

I'm keen to know more about the dynamic between Joffe and her daughter as a relationship between artist and model.

'How does Esme feel about being your subject?' I ask.

'For Esme – her dad's a painter too. So is my good friend, who has painted her. She's grown up in that world and accepts it. It's a bit like a kid growing up in the circus. Lately, she doesn't want to be painted and that's her choice.'

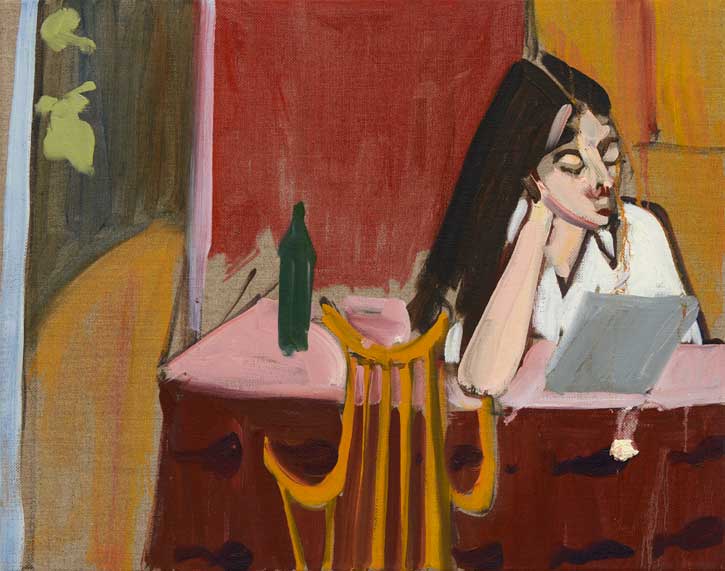

Esme at the Kitchen Table

2020, oil on canvas by Chantal Joffe (b.1969)

'It's interesting to hear this word 'choice' in the discussion of artist and model. So often we imagine a passive subject and active artist, but perhaps the relationship is more complex than that?' I venture.

'I'm meant to be the person in control but often that's a struggle for me; I should be the one asking and I'm not very good at that. It's excruciating for people who spend so much time alone,' Joffe replies. She also remarks on the difference between painting people she knows and strangers:

'I've recently painted a ballet dancer who was very in control of himself and asked me "what do you want?" This was very different compared to, say, painting a friend sitting in a chair. It's a complicated encounter, a conversation you have, a relationship, and it also brings out what the person is going through at that time, good or bad. A painting is like a photograph of mood – it contains all of those things.'

She points out that a portrait 'doesn't always go how the painter plans'.

'How so?' I ask.

'Sometimes I paint people – I see them as beautiful; in the moment I paint people they look beautiful, but the painting doesn't always come out like that. I'm not always in control – they're never quite what I hope. It's a strange, exposing experience for both parties.'

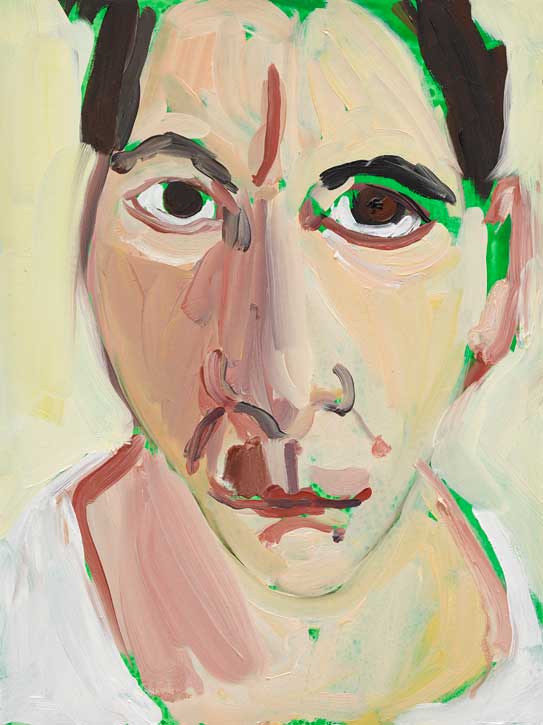

Self-Portrait After the Bath (after Edgar Degas)

2015, oil on canvas by Chantal Joffe (b.1969)

There's a truthfulness that surfaces in Joffe's painted portraits. Nowhere is this more evident than in her self-portraits, many of which will be included in an upcoming show at Victoria Miro Gallery, 'Chantal Joffe: Story'.

Joffe explains: 'With self-portraits, there are no feelings to hurt. I love it, it's pure freedom... I love seeing how far I can take the distortion, the grotesque, there's no obligation to the sitter.'

The show at Victoria Miro will also include a number of self-portraits in pastel. Joffe has turned to this new medium over the last five years, drawing with coloured pastels on her studio table, and also upon the floor.

Self-Portrait III, August

2018, oil on board by Chantal Joffe (b.1969)

'I love pastels and Degas, so it's an obvious medium,' she tells me.

There's a searching quality to the expressively applied pastel in these drawings. I remark on the depth of colour. In her reply, Joffe uses emotive terms, referring to a 'mean-looking purple'. It brings to mind the deep mauves and purples at play in Artemisia Gentileschi's theatrical paintings.

Like Gentileschi, Joffe brings an element of theatre to her portraits of women, often imagined on a large scale.

'Why do you work so big?' I ask Joffe.

'To paint big is theatrical. But then, I will retreat to smaller-sized works, depending on my mood.'

She adds: 'Being an artist is a fugitive thing.'

Chantal Joffe at Arnolfini, September

2020, photograph by Lisa Whiting

Retreating from the world to her studio, Joffe tells stories about individual women, from literary heroines to family, friends and, most candidly, herself. Enthroned in a deceptive simplicity and casually posed, these protagonists seem to be saying 'we have nothing to prove to the world' while simultaneously shouting a celebration of lived femininity from the canvas.

Ruth Millington, art critic and writer

'Chantal Joffe: For Esme – with Love and Squalor' runs until 1st November 2020 at Arnolfini, Bristol

'Chantal Joffe: Story' runs from 10th November to 18th December 2020 at Victoria Miro Gallery, London