The Second World War stirred many British artists into depicting aspects of British life during the conflict, as either factual records or spirited morale boosters. Whether it was Laura Knight's depictions of industrious factory workers, Henry Moore's drawings of the sheltering masses in the London underground, or Paul Nash's striking images of wrecked aircraft, several of the nation's leading artists utilised their artistic skills to record life during wartime.

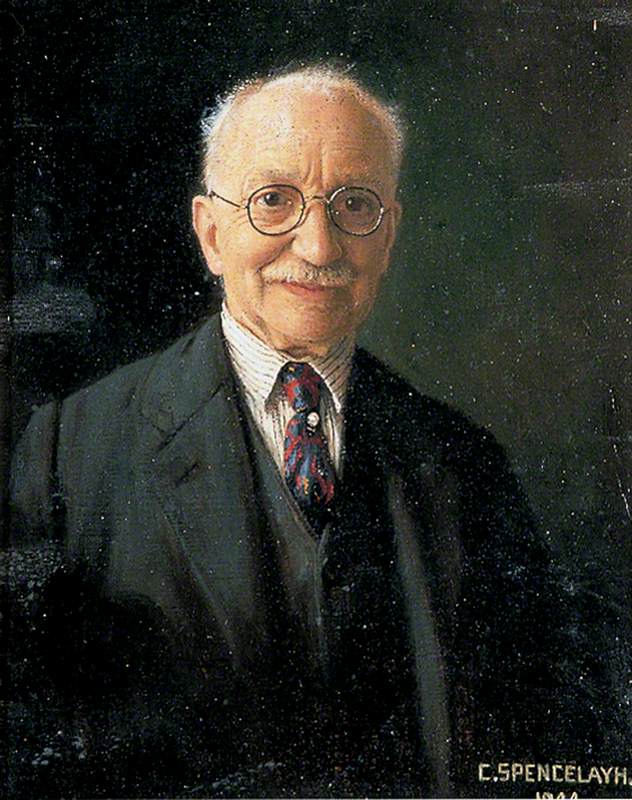

However, one unlikely artist who captured the hopes and fears and daily lives of the British people throughout the war was Charles Spencelayh.

Born in Rochester, Kent, in 1865, Spencelayh studied art in London and Paris. He specialised in anecdotal domestic interiors often featuring old men happily spending their days fixing barometers or reading Dickens and, more often than not, surrounded by a lifetime's worth of clutter. A deeply patriotic man, he was naturally compelled to paint life in wartime Britain.

Even before the fateful day of 3rd September 1939, when Britain declared war on Germany, Spencelayh had been quick to incorporate current events into his painting. Why War? was the first painting of what became a regular theme for the next few years.

The painting depicts one of Spencelayh's characteristic old men contemplating the news he has just read in the Daily Sketch, a copy of which shows a picture of Neville Chamberlain and the headline 'Premier Flying to Hitler'. Although Chamberlain famously returned from Munich proclaiming that he had secured 'peace for our time', it was not long before the likelihood of war seemed inevitable.

Spencelayh shows a First World War veteran contemplating the onset of another global conflict. On the table lies that most potent symbol of warfare, the gas mask. The juxtaposition of the gas mask alongside the mealtime crockery conveys the inevitability of war interfering with everyday domestic activities.

More subtle but no less intentional is the large print of Benjamin West's painting The Death of Nelson, which the artist has recreated in perfect detail. Spencelayh enjoyed including pictures within his paintings and he used the theme to full effect in his wartime artworks. The inclusion of this particular image is to remind viewers of Britain's military history as well as the casualties incurred during war.

When it was displayed at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 1939, Why War? was an immediate success and voted 'picture of the year'. Preston Corporation acquired the painting on the opening day of the exhibition for the then sizeable sum of £315. Due to its contemporary subject matter, Why War? received considerable attention from newspapers and magazines, many of which reproduced the image. Sensing the painting's potential commercial success, The Tatler produced special colour reproductions of it for readers to purchase.

Spencelayh and his second wife were to directly experience the destruction of the war in 1940 when their three-storied house in London was bombed. The couple narrowly escaped with their lives, but much of the artist's extensive collection of bric-a-brac and antiques – which he used for his paintings – was destroyed. Just as the Spencelayhs had got clear of the house, the front wall collapsed, leaving the rooms exposed to onlookers. In one room, however, Spencelayh's paintings which had been hanging on the walls had been turned with their faces to the wall. Typical of his sense of humour, Spencelayh remarked, 'It wasn't a compliment, was it?' Opting to live in a safer location, the artist and his wife moved to the Northamptonshire village of Bozeat.

Dig for Victory, owned by Birmingham Museums Trust, is one of Spencelayh's most interesting wartime pictures.

Rather than depicting one of his characteristic mature gentlemen, Spencelayh portrays a woman taking an active role in the war effort. With her fork, gas mask and liquid refreshment, the woman is set for a day's toil outdoors. A portrait of Horatio Nelson hangs on the wall.

The Dig for Victory campaign was launched by the British government in October 1939 in order to reduce Britain's reliance on imported food. People were encouraged to utilise gardens, parks and unused land to grow fruit and vegetables, as shown in a 1942 painting by Adrian Allinson of the Auxiliary Fire Service at work.

The AFS Dig for Victory in St James's Square

1942

Adrian Paul Allinson (1890–1959)

Spencelayh was obviously eager to show women, regardless of age, embracing the demands of the time and happily discarding the long-established gendered roles for the sake of a common cause. The Women's Land Army, better known as the land girls, became the familiar face of female agricultural labour in what was once a largely male occupation. Within this context, Spencelayh's Dig for Victory was in keeping with the spirit shown by women across Britain.

Due to the hard work of men and women of all ages, the Dig for Victory campaign was highly successful. By 1943 there were around 3.5 million allotments and around a million tonnes of vegetables were grown in the peak years of production. Spencelayh was obviously buoyed by the campaign as it gave the ordinary person (like the artist himself and his pictorial characters) the opportunity to take a hands-on role in the war and contribute to Britain's success.

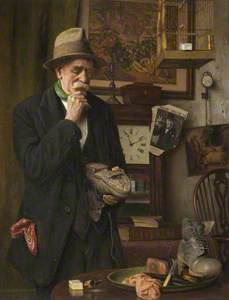

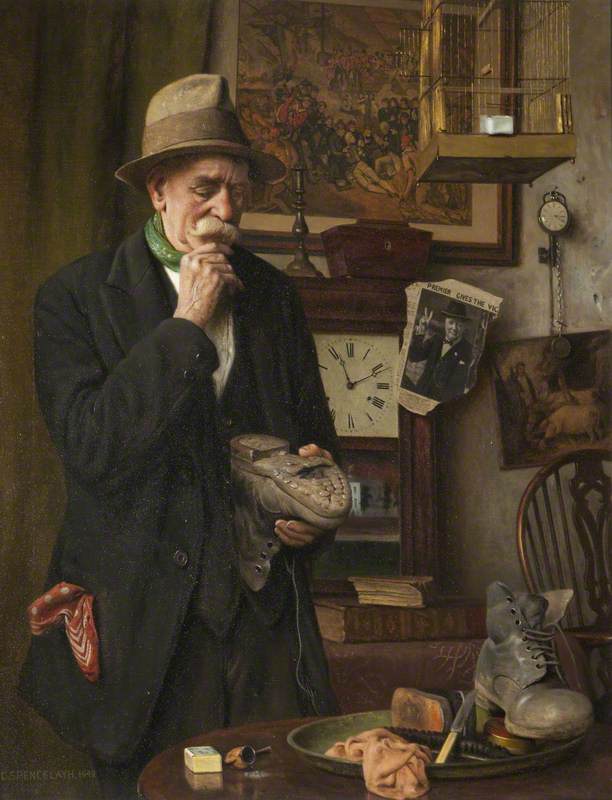

Along with growing your own food, the 'make do and mend' ethos also came to be a feature of daily life in wartime. Spencelayh took on this subject in the astutely titled, It's War.

An old man looks at the damaged sole of a boot which he ponders how to repair instead of purchasing a new pair. Perhaps the most notable aspect of the painting is the newspaper cutting of Winston Churchill giving the 'V for Victory' sign.

The theme of personal sacrifice to aid the war effort continued in Spencelayh's Your Country Needs You. The painting shows an aged man holding a gold coin that he has no doubt been saving for a rainy day.

The financial cost of funding Britain's involvement in the war was vast, and so the government encouraged people to invest in National Savings Certificates and Defence Bonds, which were guaranteed to give a good rate of return after the war. As early as 1939, a National Savings Committee leaflet stated: 'Every penny saved and applied to war purposes brings victory nearer and helps to save British lives'. Yet the gentleman in Spencelayh's painting is perhaps finding it difficult to part with his savings, especially in the midst of old age.

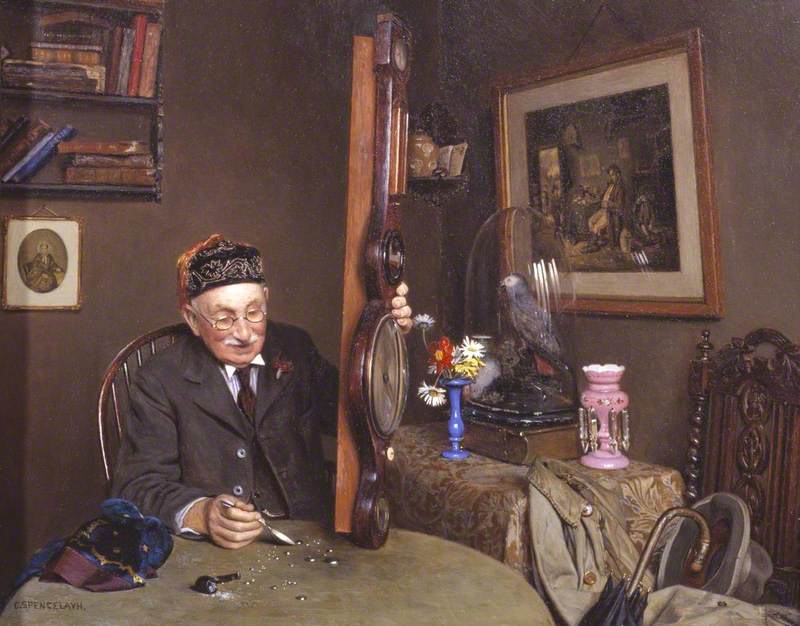

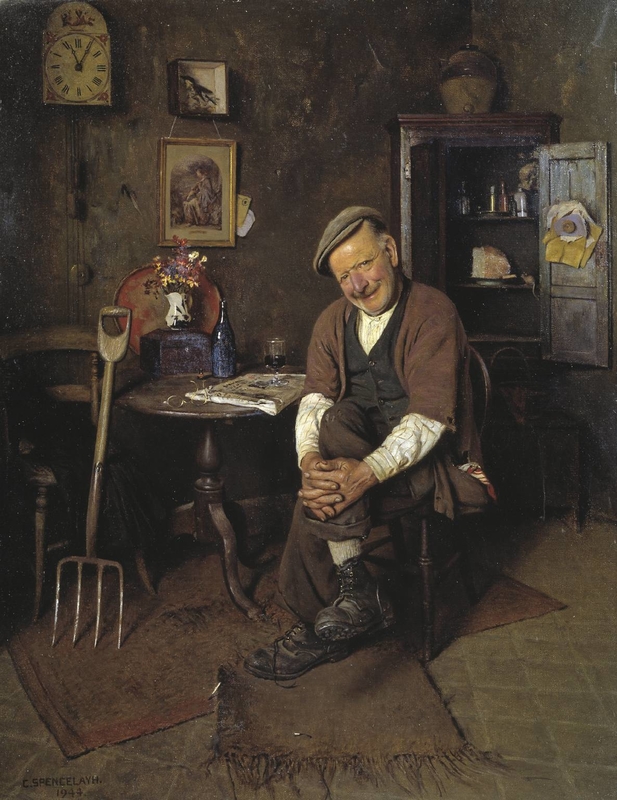

By the time Spenelayh painted War or No War, who Cares?, the direction of the war was turning in favour of the Allies.

With victory in Europe appearing ever closer, a sense of relief finally began to replace the long persistent feeling of anxiety. This change in mood is evident in War or no War, Who Cares?, which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1945 and is now in the Tate. The jovial fellow's relaxed pose and warm smile merge to create a carefree mood indicative of that felt by the British people after years of unease. The garden fork serves to remind the viewer that the Dig for Victory campaign was ongoing, but such concerns seem trivial to the gentleman.

The timing of the display of War or No War, who Cares? at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 1945 was particularly apt as victory in Europe was declared on 8th May, meaning that the painting's cheery tone directly reflected the national mood. Once again it would seem that the astute Spencelayh anticipated the likelihood of actual events and created a work that projected a light-hearted and good-humoured feeling commensurate with that felt by the British people.

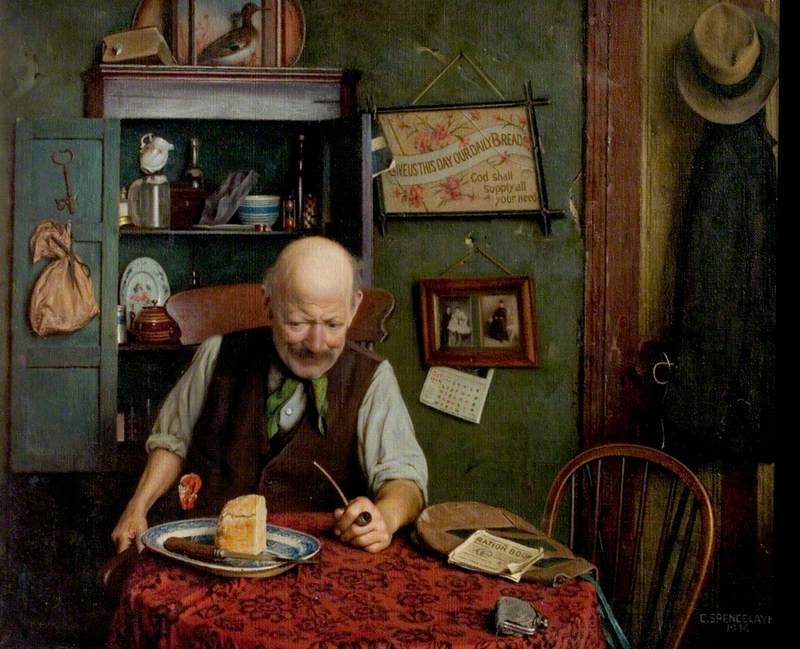

When the war was finally over, Spencelayh returned to his familiar depictions of men engaged in harmless pursuits during peaceful times. But although the war had ended, the austerity measures continued and Spencelayh still saw a worthy subject in the everyday hardships that had to be endured by the British public. His Daily Ration shows a man looking at a rather meagre piece of bread. Also on the table are his crumpled and much-used ration book, and a purse which we presume to be empty.

Although Spencelayh is not making a serious comment on the austere living standards of post-war Britain, he manages to achieve just the right balance between humour and pathos.

When viewed collectively, it becomes clear that the wartime paintings of Charles Spencelayh are an important contribution to the artistic record of British life during the Second World War. These paintings were in stark contrast to the modernist images of his younger contemporaries, but were arguably more accessible and relatable to British audiences. They capture the disquiet, stoicism and humour of a nation living through a period of unprecedented upheaval and uncertainty. They are paintings that reflect his respect for his fellow citizens and, above all, his love of Britain and its way of life.

Jonathan Hajdamach, independent art historian

.jpg)