The history of art in Ulster in the early years of the twentieth century often becomes intertwined, even briefly, with avant-garde groups and movements in England. Two short-lived, yet intriguing such encounters involve artists who themselves had an almost forgotten connection as teacher and pupil.

Edward Montgomery O'Rorke Dickey and Tom Carr were both born in Belfast to prosperous families, but their early careers were largely shaped in England, and both were briefly involved with artists who were significant in the development of modernism in England in the early twentieth century. For a short time, Carr's art master at Oundle School was Dickey, providing a fascinating meeting point between these two now underrated Ulster artists.

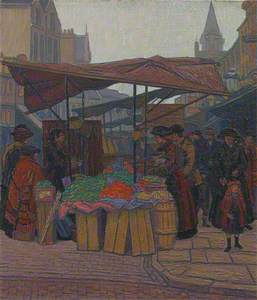

Kentish Town Railway Station

1919

Edward Montgomery O'Rorke Dickey (1894–1977)

The comparative neglect of Dickey's work is perhaps unsurprising. He turned to teaching around the age of 30 and continued a successful career in art education and museums (becoming the first curator at the Minories in Colchester) which seems to have diverted him largely from painting. Given the recognition Dickey achieved as an artist in a short period before this, and the many exhibitions with which he was involved, it is difficult to understand his decision to take up a teaching job while still so early in his career.

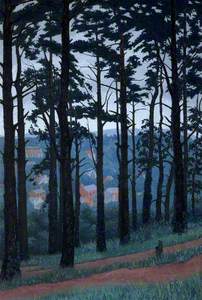

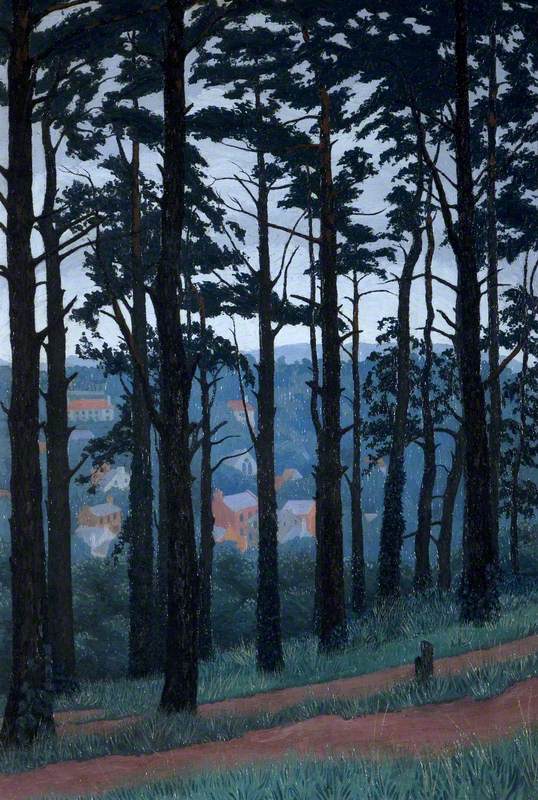

Budleigh Salterton from Jubilee Park

1925–1926

Edward Montgomery O'Rorke Dickey (1894–1977)

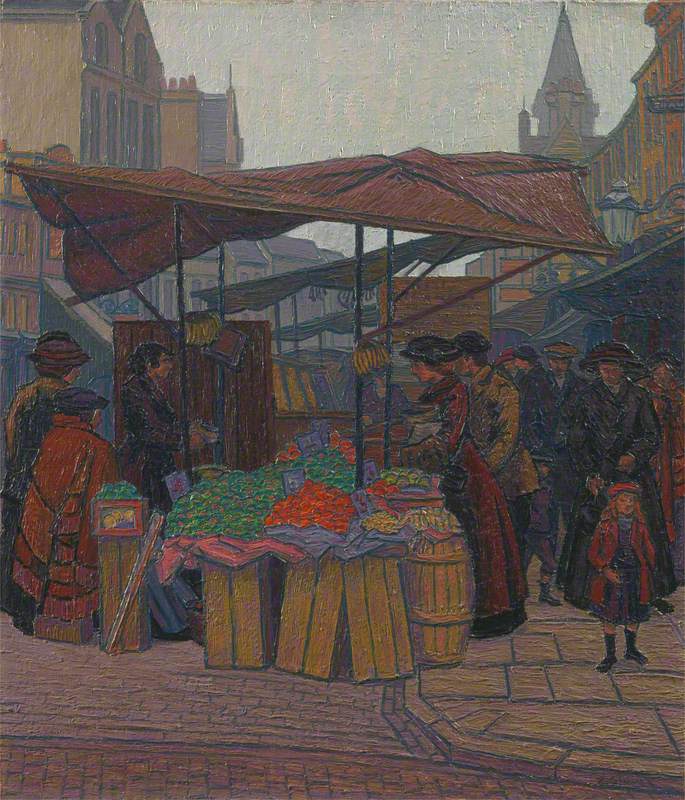

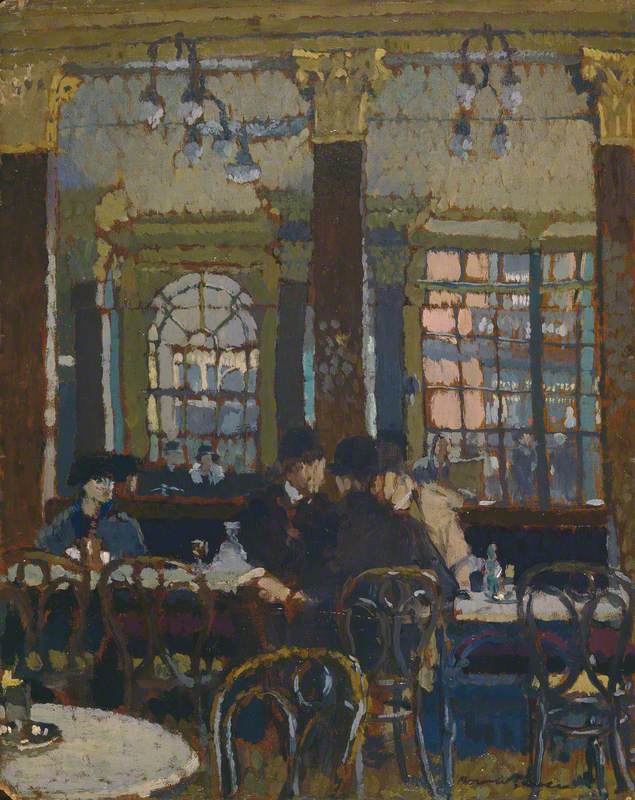

Having come comparatively late to training as an artist, only entering the Westminster School of Art after studying at Cambridge, it seems likely to have been through his teacher there, Harold Gilman, that Dickey became associated with the New English Art Club and the London Group, of which Gilman was a founder member. Dickey's earliest known works have a formal stylisation and a simplification of form, as well as a subtly imaginative tonal harmony, which resembles the work of Robert Bevan, with whom he was close. Charles Ginner was another friend, and Dickey was also associated with the Bloomsbury Group at this time, as a member of Vanessa Bell's Friday Club.

Landscape in the Blackdown Hills, Devon

1917

Robert Polhill Bevan (1865–1925)

Although he appears to have been based mostly in England, Dickey painted a number of subjects from the country of his birth. Predominantly interested in landscapes, he seems to have enjoyed the dramatic outlines of the Mourne Mountains and their powerful profile across much of the County Down landscape. In addition to the groups with which he exhibited, Dickey also held several one-person exhibitions in the early 1920s, including at the Leicester Galleries (where his work was shown alongside that of Vincent van Gogh) and Manchester City Art Gallery.

In 1920, from an address in Percy Street, London, at the heart of Fitzrovia, Dickey showed three paintings at the Belfast Art Society, continuing to exhibit there when he moved back briefly to Antrim in 1921, but he sent no paintings there after 1925. He was also involved with the establishment of the Dublin Painters Society in 1920, demonstrating the swiftness with which he had become accepted across Britain and Ireland as a significant modernist painter. Indeed, the Irish Times described him in 1922 as 'possibly the most experimental painter working in Ireland'. S. B. Kennedy notes his close association there with Jack B. Yeats and Paul and Grace Henry, while noting that while few 'of the works which they exhibited were daringly avant-garde…they shared a keen awareness of recent developments in painting'.

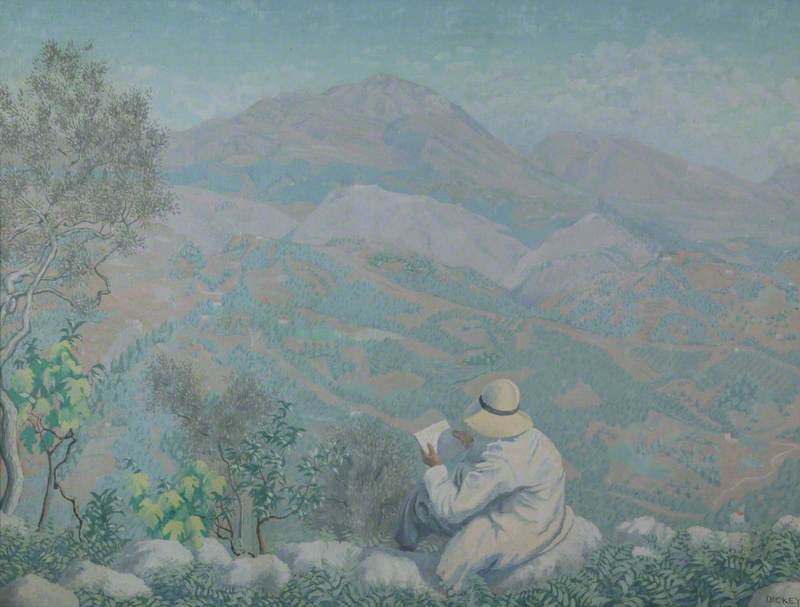

Monte Scalambra from San Vito Romano

1923

Edward Montgomery O'Rorke Dickey (1894–1977)

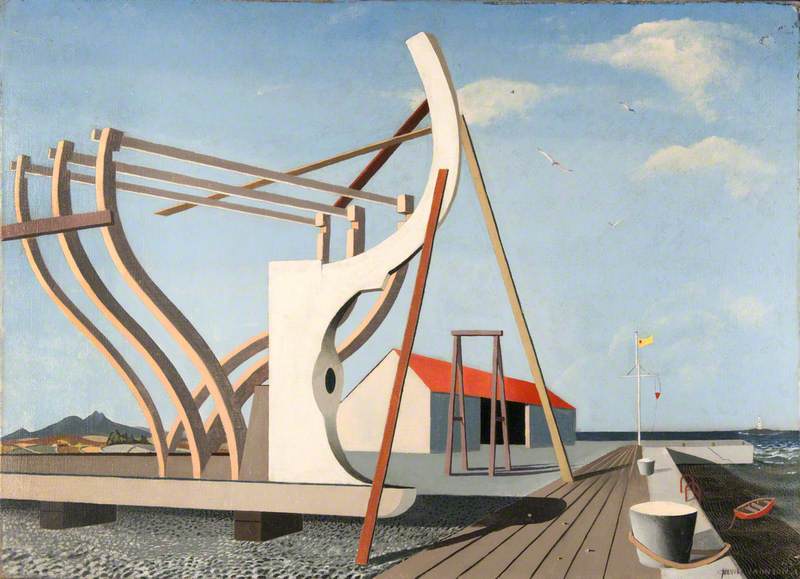

Dickey also travelled to Italy in the early 1920s, finding plentiful subjects for his work there. It is also possible that he became aware of the Futurists during that time, as their influence is occasionally apparent in his printmaking. It is, arguably, as a printmaker that Dickey was best known at the time, and also found his most progressive modernist voice. In 1920 he was one of the eleven artists who formed the Society of Wood Engravers, and in 1923 he made a number of illustrations for Workers, by his friend R. V. Williams. Some of his hard-edged linocuts reinvigorated traditional Irish iconography and demonstrate the interest in Ireland at that time in identifying a modern national visual identity.

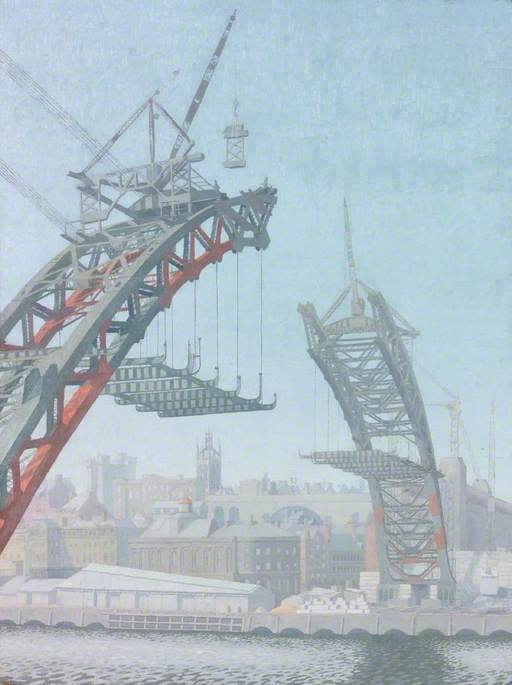

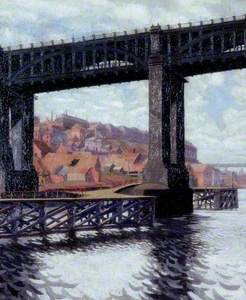

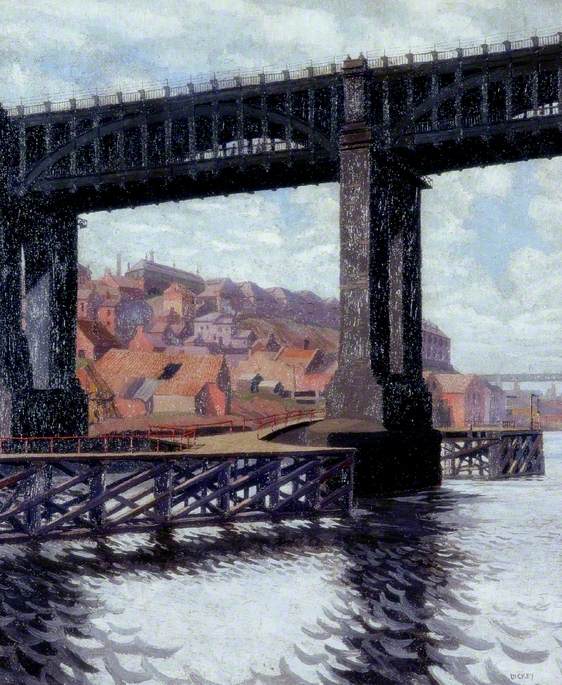

Robert Stephenson's Bridge (The High Level Bridge)

c.1927

Edward Montgomery O'Rorke Dickey (1894–1977)

Despite his regular solo and group exhibitions, which achieved notable critical success, such as in The Studio, where it was noted that '[h]is admirers look for great things from him in the near future and are not likely to be disappointed', Dickey decided to take up a teaching job. He continued to paint after moving to Oundle to teach art and also when he took up a post as Professor of Fine Art and Director of King Edward VII School of Art in Newcastle, but he exhibited less frequently. Moving into the Ministry of Education, he was appointed secretary of the War Artist's Advisory Committee in 1939, working closely with Kenneth Clark, then Director of the National Gallery.

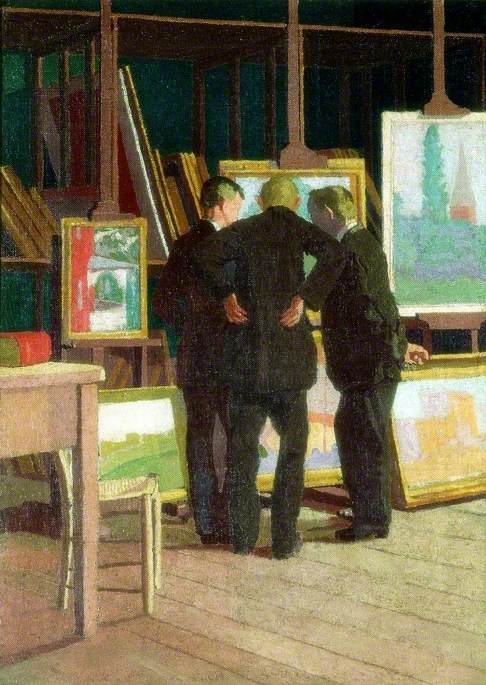

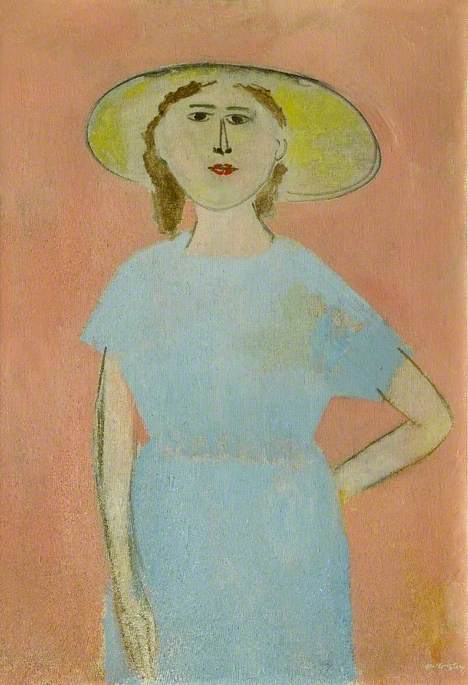

It was in the mid-1920s that Dickey taught Tom Carr. Although Carr recalled how little he enjoyed his schooldays at Oundle, his talent as an artist must have been obvious even then, as on leaving the school he spent three weeks on a painting holiday in the south of France with another Oundle art teacher, Christopher Perkins, and his family. Accepted into the Slade School in London around 1928, Carr was a contemporary of two other notable students from Northern Ireland, F. E. McWilliam and John Luke, but he was more closely associated with a group of English fellow students who included William Coldstream, Rodrigo Moynihan, Geoffrey Tibble and Claude Rogers. In the early 1930s, he also met Victor Pasmore and Graham Bell, and was included in the 1933 'Objective Abstraction' exhibition at the Zwemmer Gallery, alongside a number of these friends, as well as Ivon Hitchens and Ceri Richards.

Fitzroy Street (William Coldstream and Graham Bell in an Interior)

c.1935

Geoffrey Arthur Tibble (1909–1952)

Although Carr admitted that he was not by nature an abstract painter, his inclusion demonstrates an early attraction to the avant-garde. He fitted more naturally into the Euston Road Group, who included Pasmore, Coldstream, Bell, Tibble, Moynihan, Rogers and Lawrence Gowing; the realism of their work, and the selection of subjects drawn from everyday life, was in many ways a reaction against the abstraction that was beginning to dominate British art. In some ways, one might trace this group back to Walter Sickert, and John Hewitt made the connection between Sickert's work and that of Carr, as well as Vuillard and Bonnard, noting that 'it is in the company of those masters of quiet acceptance that Carr finds his own climate and significance.'

Like Dickey before him, in 1933 Carr took lodgings in Fitzrovia, an area full of recent artistic history, where Sickert, Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell had all had studios; most of the Euston Road Group were neighbours, and the critic Adrian Stokes also had a room in the same house.

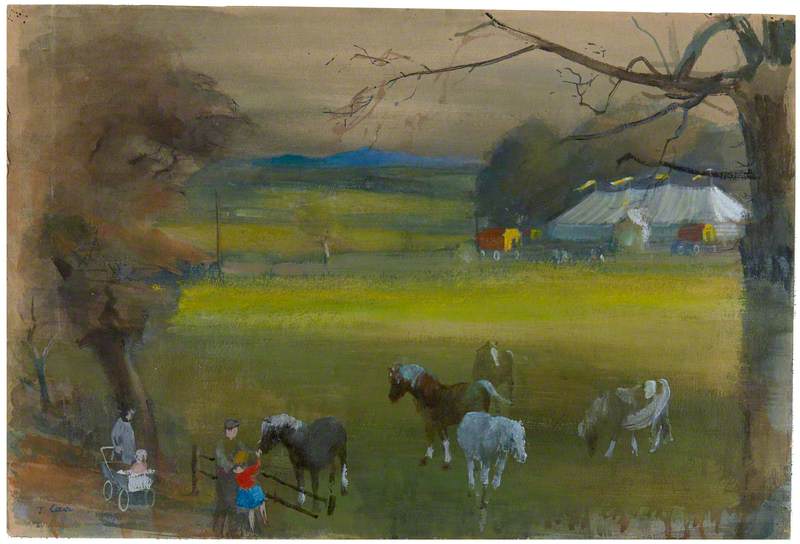

Carr's first solo exhibition, in Canterbury, took place in 1939, and although he continued to show in London during the war and in the second half of the 1940s, Carr began to be drawn back to Ireland. In addition to the safety from the war offered by the Ulster countryside, he was also invited to exhibit with Graham Bell in Dublin, at the Contemporary Pictures Gallery, for which both painted a number of Irish subjects. Despite the lack of sales and any positive critical response to this exhibition – in addition to his ambivalence towards Newcastle, a seaside town near the Mournes, where Carr, his wife and their young daughters, spent much of the war – he seems to have gradually come to accept the country of his birth as his home again.

Carr took on a commission from the War Office and also painted girls sewing parachutes in a factory while based in Northern Ireland, but he continued to exhibit with some of the leading galleries in London throughout the war and in its immediate aftermath. He was also invited to contribute a work to the 1940s School Prints series, alongside artists including Henry Moore, Julian Trevelyan and John Tunnard.

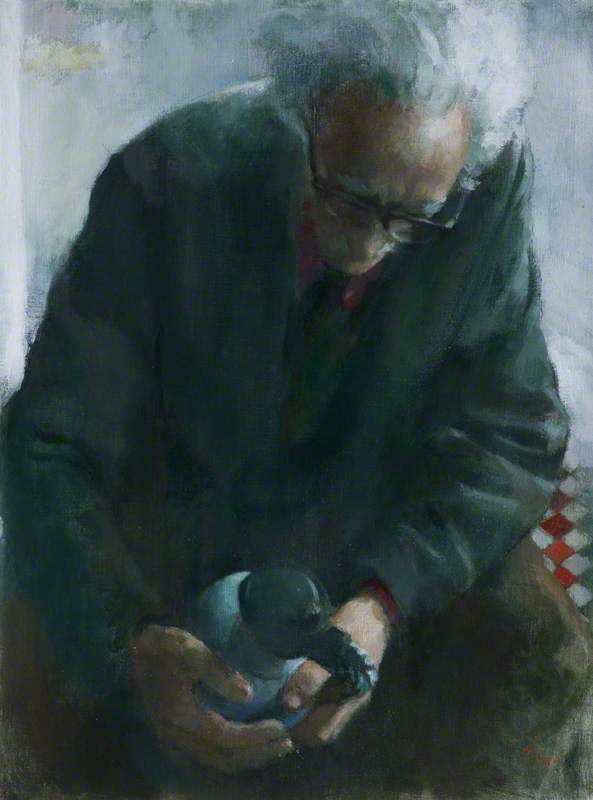

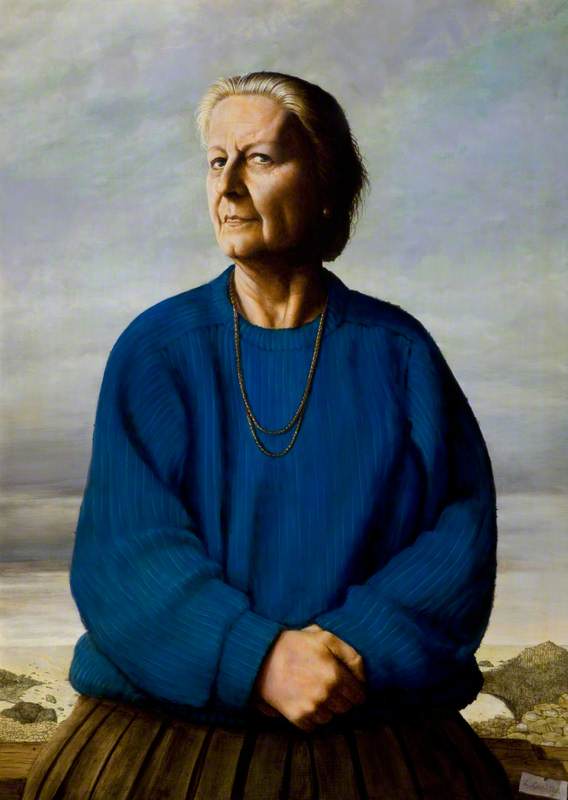

From the 1950s, Carr's work became more concentrated on the Northern Irish landscape, as well as occasional portraits and occasional domestic scenes that often included his daughters. Like Dickey before him, Carr became less closely involved with the London-based modernist artists with which he had been associated. Still, unlike his teacher, who eventually moved away from regular exhibiting, Carr worked almost until his death in 1999 and continued to show work with great success. He became perhaps best-known as a watercolourist in the 1960s and 1970s, often working on a large scale, with the critic of the Irish Times, Brian Fallon commenting on the 'freshness, brilliance, lyricism and superb technique' evident in his work in this medium.

O'Rorke Dickey, despite his involvement at such a notable time in its development, has remained largely neglected within the canon of modern Irish art. Only a small body of work is known, with only occasional Irish subject matter, but his landscapes are clearly independent of any other work being made in Ireland at that time. While the link between London and Belfast shaped much of the development of art in Northern Ireland during the early twentieth century, Dickey's friendships with artists such as Gilman, Bevan and Ginner, and the quality of his early work – which led Kenneth Clark to describe him as a 'serious painter' – provides an unusually early and impressive modernist connection.

Carr's involvement with avant-garde exhibiting groups in London was also comparatively short-lived yet, in a lengthy career, it remained a period that shaped much of his identity as a painter. He brought something of this influence to Northern Ireland with him and he is undoubtedly a significant figure within twentieth-century Irish art history, yet the qualities and values that drove him as an artist are perhaps overlooked today. While both remain somewhat under-appreciated in their homeland, it is also interesting and perhaps equally relevant to re-appraise their work within the British context of which they were initially a notable part.

Dickon Hall, art historian and Art UK Content Commissioner, Northern Ireland

Further reading

Theo Snoddy, Dictionary of Irish Artists: Twentieth Century, Merlin, 2002

S. B. Kennedy, Irish Art and Modernism, Institute of Irish Studies, 1993

Eamonn Mallie, Tom Carr: An Appreciation, Express Litho Limited, 1989