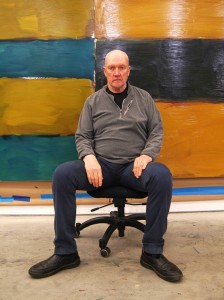

Jon Groom's diverse practice ranges in scale between the intimate and the expansive, in watercolours and drawings, single and multi-part canvases, and large wallpaintings. The artist trained initially at Cardiff College of Art, firstly in sculpture before then switching to painting, and in relation to this he has recently stated: 'I studied sculpture so I could early on find out independent ways to work as a painter. I never really felt like a painter, although I like the world betwixt these two practices.'

'I studied sculpture so I could early on find out independent ways to work as a painter.'

— Art UK (@artukdotorg) November 27, 2017

New story on the abstract paintings of Jon Groom, written by @IanMasseyArt https://t.co/YZPvOOeiPu#art #artist #contemporaryart #painting pic.twitter.com/ZwXWxjy0v6

Whilst Groom's economic abstract language can be seen to derive from the aesthetics of minimalist painting, sculpture and architecture, his work operates at a more subjective level than this might suggest, for it has over time become noticeably more imbued with a sense of the spiritual and humanistic. In this, colour and surface are crucial.

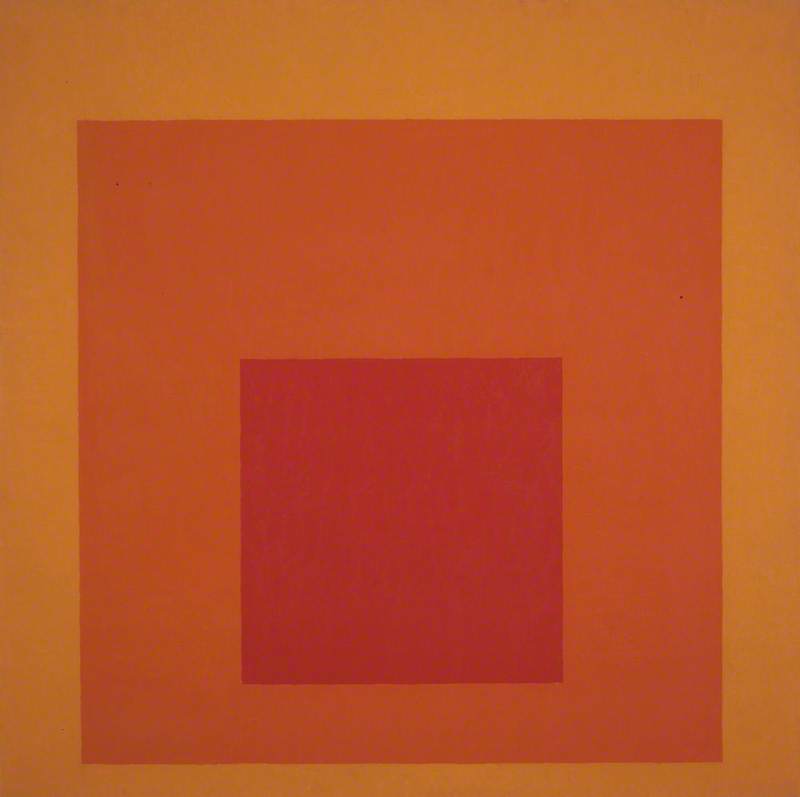

Groom has cited how studying Rothko's newly installed Seagram murals at the Tate in the early 1970s proved a key moment for him, the point at which he understood more deeply than hitherto the potential for colour to evoke an emotional response.

Another important source of inspiration was space and colour in the architecture of the Luis Barragàn, whose work Groom studied during a residency in Mexico City in 1997. Later, towards the end of that decade, there began a deep interest in Eastern philosophy and spirituality, the impact of which became evident in the increasingly meditative nature of his work.

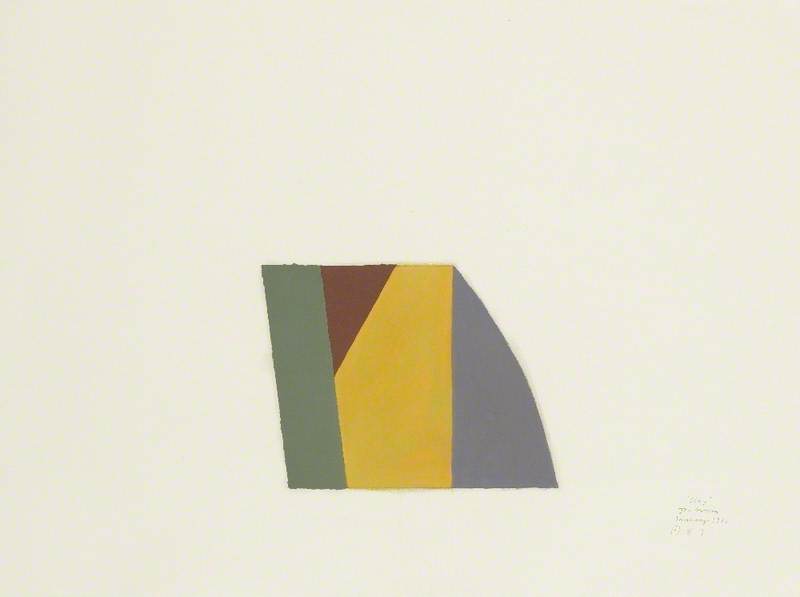

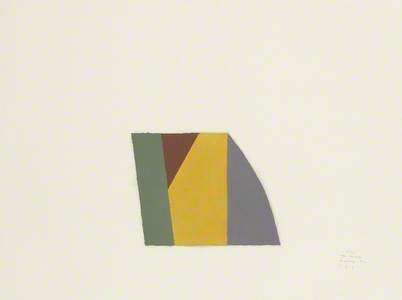

Of Groom's four works on the Art UK site, the earliest is Untitled II (1979), from a series of shaped canvases collectively entitled Vertical Wall-Bound Arcs, eight of which were shown in the artist's first London show, at the Nicola Jacobs Gallery in 1979. Some of these – as is the case in the example here – consisted of a single canvas, whilst others were formed from two adjoined canvases set at slightly tilted angles. On each is drawn a fine arc, akin to a wire set in tension, that disrupts and makes play with the overall formal structure. Of this group of works, Groom has written:

'The paintings are about 6cms deep, and are very object-oriented. The spachtel [spatula] technique was used to build up multiple layers of paint.' Asked about the uneven edges of three of the sides of Untitled II, the artist provided the following insight: 'The ragged edge appealed to me. Firstly, it seemed to integrate the colour with the wall, and secondly it gave a very naturally formed edge in striking contrast to the other hard edges. So to sum up, it was a result of the spachtalling, which became incorporated into the entire series. The arcs were drawn in after the ground. A thin tape was then attached to the edge of the pencil line. With the successive layers of matt acrylic I lost all evidence of the tape. At top and bottom the tape overhung the edge, and when the required matt and even surface was completed, and all evidence of the thick canvas could no longer be seen, the tape was pulled out. I might add that people gathered around to watch what looked impossible. The trick is to mix the acrylic in such a way that the paint is free to fracture on each side of the tape. Again, I wanted the physicality of a line, and not a painted line.'

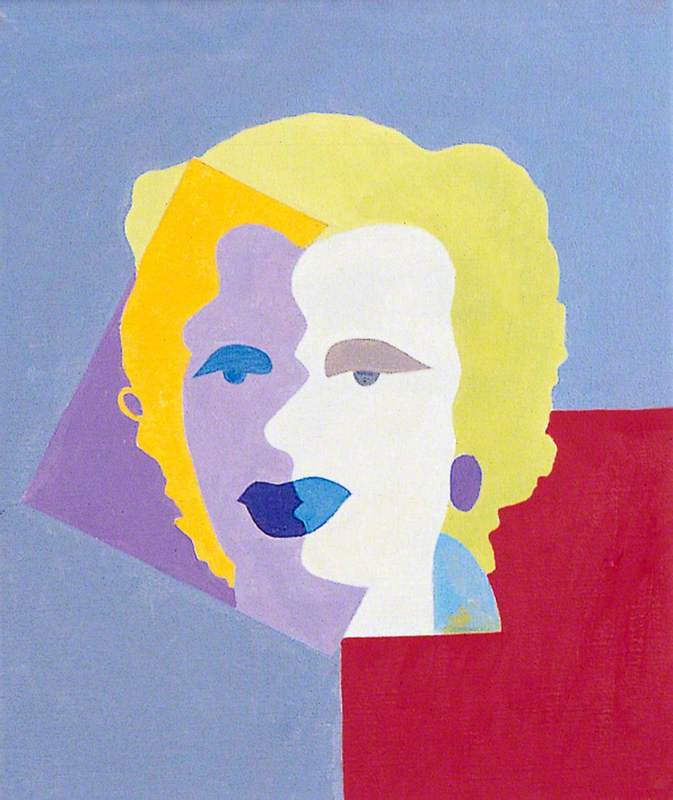

In comparison, two works from the early 1980s, Clay (1981, oil on paper) and The Moorish House V (1982) are structurally more complex, their geometric forms as though folded or closely locked together, and both with a single curved edge providing a sense of directional movement. Each is from a series of works: those titled Clay suggest the human clay; whilst a group made in parallel titled Unclay imply the body unbound, released.

The Moorish House paintings were based on an essay by Albert Camus, from which Groom wrote in a notebook a quote that provides a clue into the paintings' formal intersections: 'Watching the sea, very far away, flat, serene, where tug boats trace great straight lines fanning out in shudders of foam – Then the calmness of the waters joins that of the sky.'

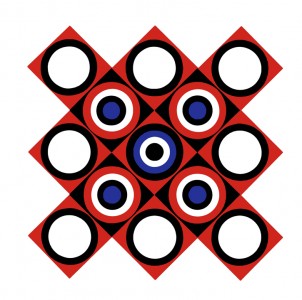

From the 1990s onwards Groom's work became formally simpler, centred on square or rectilinear shapes, and hence more focussed on sensitivity to interrelationships of shape, edge and colour. Equally, there is an emphasis on surface, with subtly inflected textures achieved by mixing minerals into the paint. An example is Between the Light #10 (2006), in which finely-judged formal repetition is modulated by immensely delicate vibrations of layered colour.

Groom was amongst the first customers of Kremer Pigments, a company that opened stores in Munich and New York which sold pigments and minerals in powder form: 'I always wanted the extreme physicality of surface to be so material that they were transformed into the ethereal; so by experimenting with minerals like silica, quartz and other mineral deposits in powdered form the paint has a sort of stone like quality. I was after a type of paint that did not read as paint.'

Commenting on Groom's work in 1983, Chris Titterington wrote of: 'the need to make reference to the immaterial as a natural concomitant of the material – of the spiritual in the corporeal.' This it seems to me encapsulates the essence of Groom's work and helps to explain its power; as does a final statement from the artist himself: 'I think the success of my paintings – at least I hope – is that they read not as technique, but that they transcend the obvious.'

Ian Massey, art historian and curator

The exhibition 'Angles of intent', including Jon Groom's work, was open in November and December 2017, and January 2018 at Galerie Nanna Preußners, Galeriehaus Hamburg

References

Quotes by Jon Groom are from an email correspondence with the author, September 2017

Exhibition catalogue Jon Groom: Calling, Clearing, Soprano with essay by Chris Titterington, Rochdale Art Gallery, 1983

Beate Reifenscheid & Robert C. Morgan, Jon Groom: Between the Light, Prestel, 2006