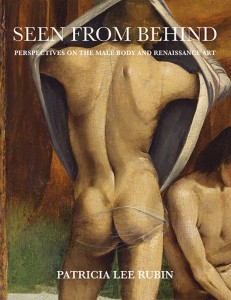

In recent times there has been a sustained focus on the role of women in art history, not just as artists but also as subjects. Many would agree that, historically, women in art have often been objectified and their appearance in paintings determined by how male artists and male patrons have perceived them via male-constructed notions of femininity or sexual appeal.

The Toilet of Bathsheba

after 1705

Luca Giordano (1634–1705) (style of)

The recurring subject of the female nude is an obvious example of this. One of the unlikely origins of this can be found in Christian art, specifically images of the Old Testament figures Susanna and Bathsheba.

Both women feature in stories where they are spied upon whilst bathing. These narratives, perhaps unsurprisingly, proved popular among male artists who needed little excuse to paint a sensual female nude, especially as the biblical sources of both stories provided a guise of respectability.

Depictions of Susanna and Bathsheba are among the first examples of the male gaze in art: namely, how women are portrayed physically from the perspective of a male viewer. Yet many of these paintings reveal contradictions and more profound questions around nudity, beauty, voyeurism, decency, temptation and chastity.

The story of Susanna and the Elders is one of the Apocryphal additions to the Old Testament Book of Daniel. Susanna was the beautiful and virtuous wife of Joachim, a respected figure in the Jewish community in Babylon. One day she was bathing in her garden. Unbeknown to her, two lecherous elders who were powerful but corrupt judges were spying on Susanna. They approached her and demanded that she comply with their sexual desires. She refused and they falsely accused her of adultery, for which the punishment was death. She was found guilty at her trial but the prophet Daniel interrogated the old men and discovered inconsistencies in their stories. They were then sentenced to death and the innocent Susanna was praised for her devotion to truth.

Susanna featured in early Christian art as an example of chastity over lust and righteousness over sin, but by the post-Renaissance period, the subject appealed to artists less for its moralising themes and more for its erotic connotations.

Susanna and the Elders

1555/1556, oil on canvas by Tintoretto (1518–1594)

Tintoretto (1518–1594) painted a famous version of the story showing a voluptuous nude Susanna radiating light in a garden landscape. The prying elders are well hidden. Compositionally, Susanna dominates the picture and Tintoretto ensures our attention is directed towards her, making the viewer a third voyeur in the scene. However, there is a notably troubling aspect to how Susanna has been portrayed. She is shown gazing into a mirror and surrounded by luxury objects, implying that she is interested in her own beauty, suggesting that the men's intrusive behaviour is somehow justified.

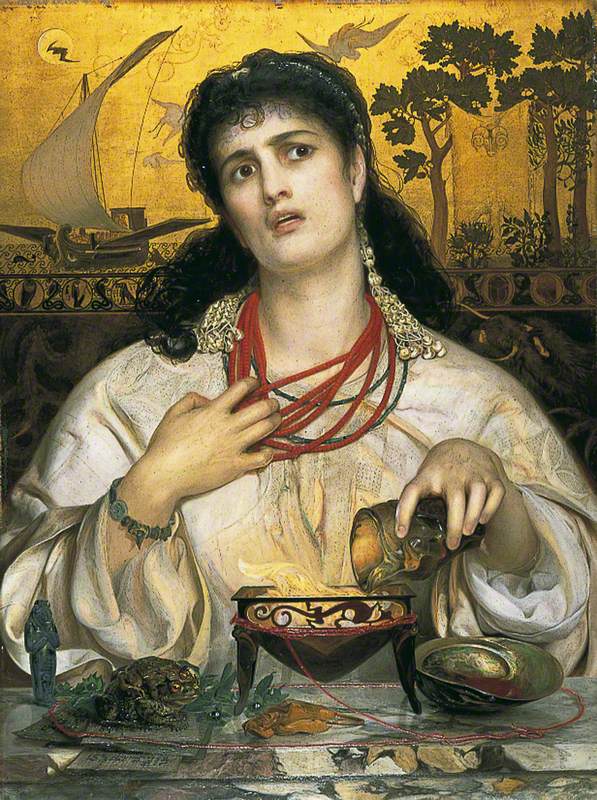

By the Baroque era, the Susanna story reached the height of its popularity. For Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654 or after), the subject possessed an uncomfortable relevance. She was one of the few women artists to paint the Susanna and the Elders narrative. As a young woman in Rome, she had fended off sexual advances by men prior to being raped by a fellow painter in 1611.

Susanna and the Elders

1610, oil on canvas by Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654 or after)

Her painting of 1610 differs from versions painted by men as it shows the elders looming over the diminutive Susanna in a physically oppressive manner. Her emotional distress is reflected by her twisted, awkward posture. With no background, the painting has a claustrophobic intensity and the feeling of intimidation is palpable. Gentileschi brought not only a female perspective to the story but also an empathetic response based on her own experiences.

A more typically Baroque approach to the story can be seen in a painting by Giulio Cesare Procaccini (1574–1625). He used chiaroscuro to heighten the drama of the scene, whereby the two men emerge from the shadows and accost Susanna, whose entire body is starkly lit. By illuminating Susanna in this way, Procaccini allowed the viewer (presumably male) to study almost every part of her body.

The roughness of the fully robed men serves to emphasise the nakedness and idealised beauty of Susanna. Also, the two men are no longer passive observers. One of them has his hand on Susanna's right arm, making this an act of physical violation.

Procaccini's painting encapsulates the obvious contradictions when portraying Susanna and the Elders. On the one hand, he is unashamedly presenting the nakedness of Susanna for the visual pleasure of the viewer, while on the other he is directly addressing her vulnerability and distress.

Two paintings by Guido Reni (1575–1642) reveal contrasting approaches to the story. In the first, held in The National Gallery, he follows previous examples by showing an undressed Susanna whose body is well lit against the darkness. She seems slightly surprised rather than alarmed by the presence of the elders.

In the second painting, Reni shows Susanna concealed by her robe and not nude, which was unusual at the time. However, he depicts her being manhandled by the lascivious men. She pushes one away but is trapped between them. There is no titillation here, only the uncomfortable sight of Susanna trying to free herself from the men's physical persistence. This version is a rare example of the story being presented as an instructive lesson in the importance of male sexual restraint, which the two men evidently do not possess.

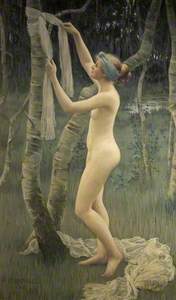

The Susanna story continued to be popular in the eighteenth century but without the intensity favoured by Baroque artists. In Louis Jean François Lagrenée's version, the two men are less menacing than seen in earlier depictions. One appears on bended knee almost pleading for Susanna's attention.

Also, pastoral woodlands have become the setting, as if to soften the troubling nature of the story. Susanna herself is presented more like a wood nymph than an ordinary woman being harassed by old men.

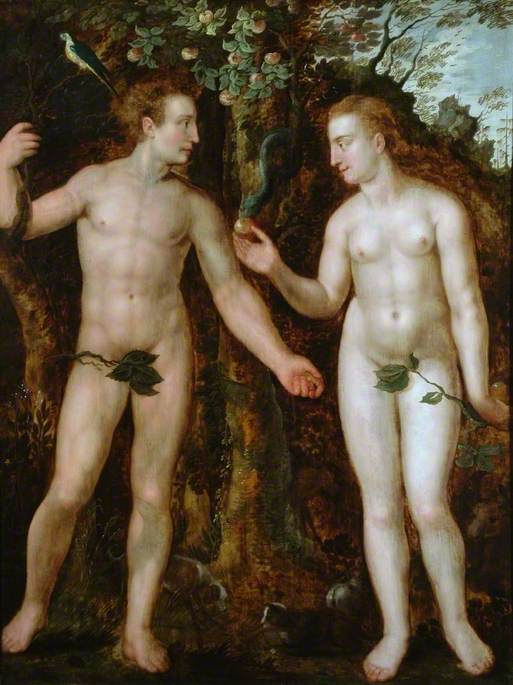

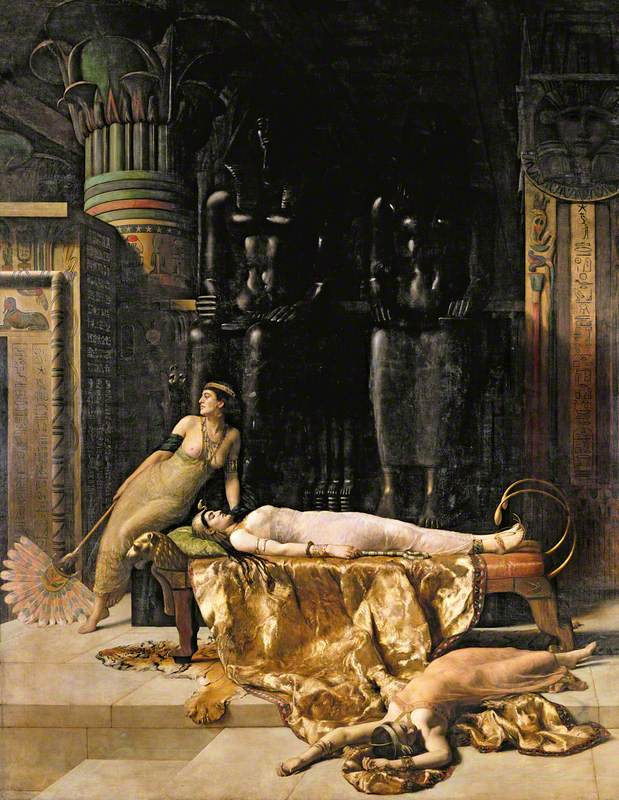

The story of Bathsheba is told in Samuel 2:11. One evening, King David was walking on the roof of his palace from where he saw Bathsheba bathing. She was the wife of Uriah the Hittite, one of David's soldiers. David seduced Bathsheba and she became pregnant. David ordered Uriah into battle knowing he would meet certain death. David repented but was punished by the death of his child.

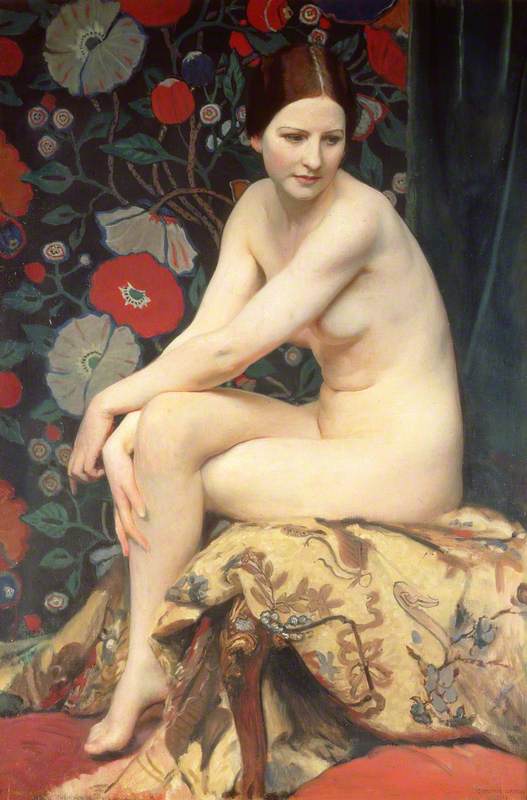

Typical of many depictions of Bathsheba is a painting by Johann König (1586–1642). Bathsheba is shown in a lavish setting, accompanied by her attendants. David, almost incidental to the scene, can be spotted on the roof in the distance.

The way in which Susanna is presented – fully nude, surrounded by luxury objects, not unlike Tintoretto's Susanna – suggests she is narcissistic and an exhibitionist, therefore justifying David's distant but lingering gaze.

In a painting of Bathsheba by a follower of Hendrik van Balen I (1575–1632), she is shown in an almost identical pose, in opulent surroundings and alongside exotic animals. The youthful female body is evidently seen as a prized possession worthy of male attention. Interestingly, the richly fertile garden setting was considered by artists as a traditional metaphor for the bountiful femininity of nature. Tintoretto used this in his Susanna and the Elders.

In a vast canvas by the Flemish painter Pieter Thys (1624–1677), Bathsheba is looking at us while assisted by her maid. The viewer is caught in the act of looking. Like David from his rooftop, we are also drawn to the naked figure of Bathsheba, but we are no longer the unobserved onlooker. Thys questions whether voyeurism is a harmless act or, as Bathsheba's gaze suggests, an uncomfortable experience for the person being viewed.

A painting by David Wilkie (1785–1841) from 1817 is a more modest take on the theme. While Bathsheba prepares to bathe, her attendant looks back as if aware of prying eyes. Wilkie's picture is less sensationalist than earlier versions, perhaps reflecting British social attitudes of the time, which saw artists who painted the female nude often accused of indecency.

By creating images of Susanna and Bathsheba, artists from past centuries set a precedent for how women would be portrayed in art that continued well into the era of modern art, and which can still be seen in contemporary visual imagery.

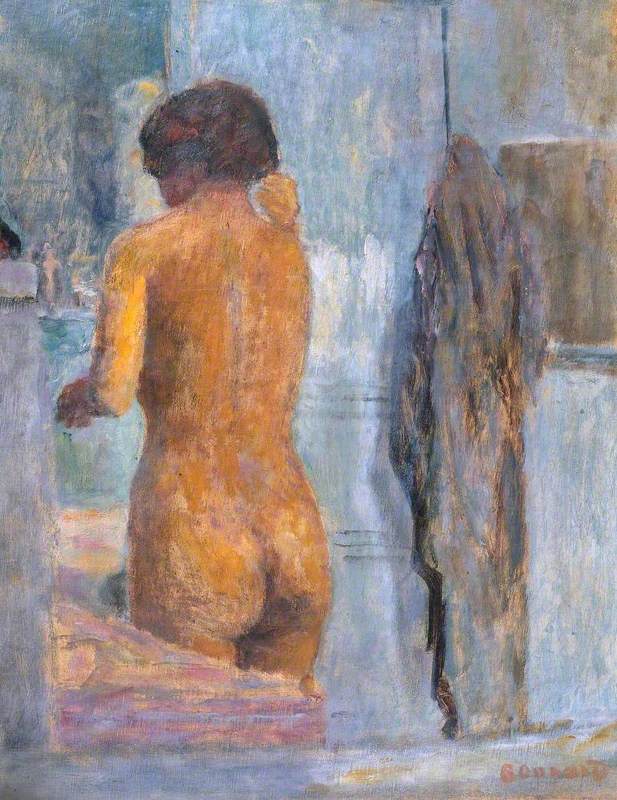

Edgar Degas (1834–1917), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) and Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) were just some of the modern greats who routinely painted women in the act of bathing. And even without any religious context, their paintings followed a tradition established by depictions of Susanna and Bathsheba painted centuries earlier.

Jonathan Hajdamach, independent art historian

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation