If Northern Ireland seemed to slip from British imagination and discourse after the 1998 Good Friday Agreement (GFA), which marked an end to the Troubles (1968–1998), it has now returned to play a crucial role in Westminster politics. The confidence and supply arrangement between the Conservative Party and the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) has brought the province to the forefront of British public attention.

Brexit negotiations too have been overshadowed by the question of the border between Ireland and Northern Ireland, and the 2016 referendum has led to renewed calls for a border poll on reunification with the Republic. Land, of course, is at the heart of the conflict. It is in the imaginative terrain of landscape that ideas of war and peace, mastery and powerlessness are mapped.

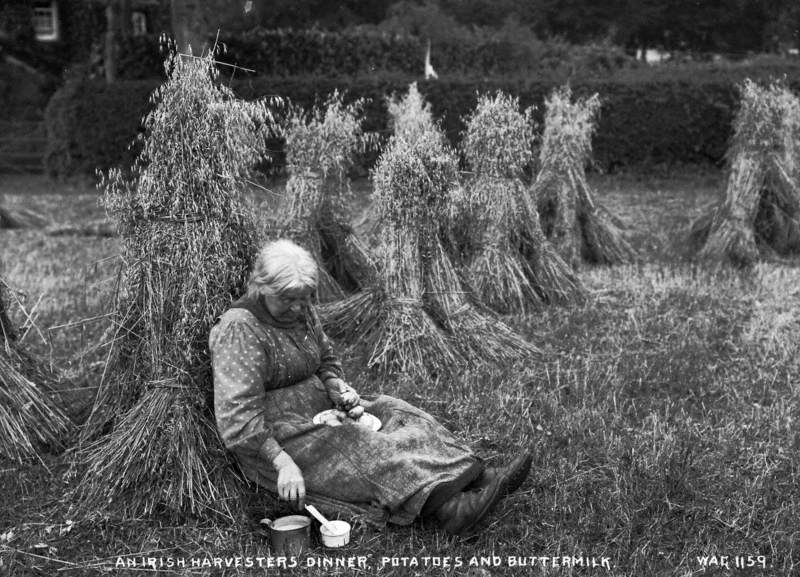

The Kingdom of Ireland and the Kingdom of Great Britain were brought into political union through the 1800 Acts of Union. The nineteenth century was a violent, turbulent time for Ireland. The country was ruled by absentee Protestant landlords, over a largely Catholic tenant population.

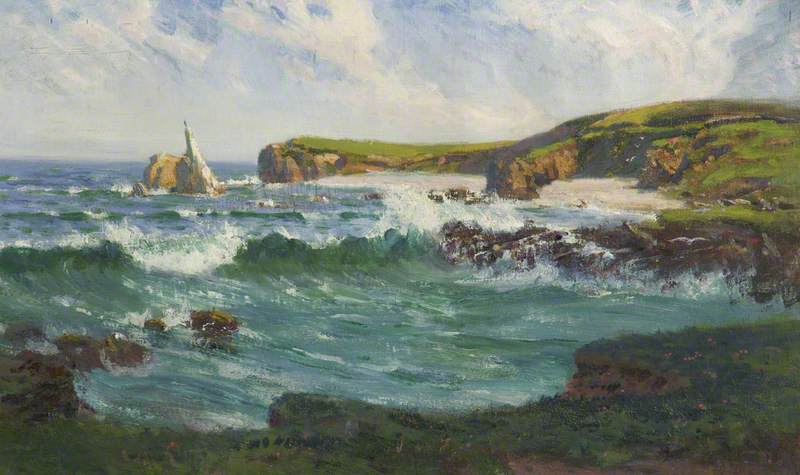

Agitations for Home Rule and independence increasingly grew in momentum, particularly in the wake of the Great Famine (1845–1852), in which roughly a million died and a million emigrated. On first impression, it might seem that British and Irish landscape painting tells a different story: one of tranquillity and peace.

Falls of Powerscourt, near Bray, Co. Wicklow

Richard Sasse (1774–1849), watercolour on paper, 1818

There is always a politics at play in representing the landscape. In English artist Richard Sasse's Falls of Powerscourt, near Bray, Co. Wicklow, cattle graze peacefully by a waterfall in the golden glow of afternoon sun. A gentle, reassuring image, picturing nature as giving – the trees framing a shelter, the cows promising food.

Other British artists toured Ireland, painting the countryside with similar tranquillity: Alfred Fripp's Galway Woman and Child and Francis Topham's Feeding Chickens romanticise peasant life as simple and harmonious.

From a British perspective the intention is obvious: a picture of Ireland as bounteous, benign and content would have been reassuring to those back home.

Irish artists like Bartholomew Watkins also painted pastoral scenes at times of mass death and violent upheaval, but to different ends. Ruins on Inniscaltra, Lough Derg, for example, casts a scene of cattle grazing amid fragments of early Christian ecclesiastical buildings, a warm light silhouetting them against a spectacular sunset.

Like Sasse's watercolour, this work represents the natural world as peaceful and providing. But unlike Sasse, Watkins chose a specific location to evoke an image of Ireland before British rule – to also imagine a future time in which the country regained its sovereignty. A renewed interest in Ireland's past drove the Celtic Revival in the arts, which fed (and was fed by) increasing momentum behind the Home Rule and independence movements.

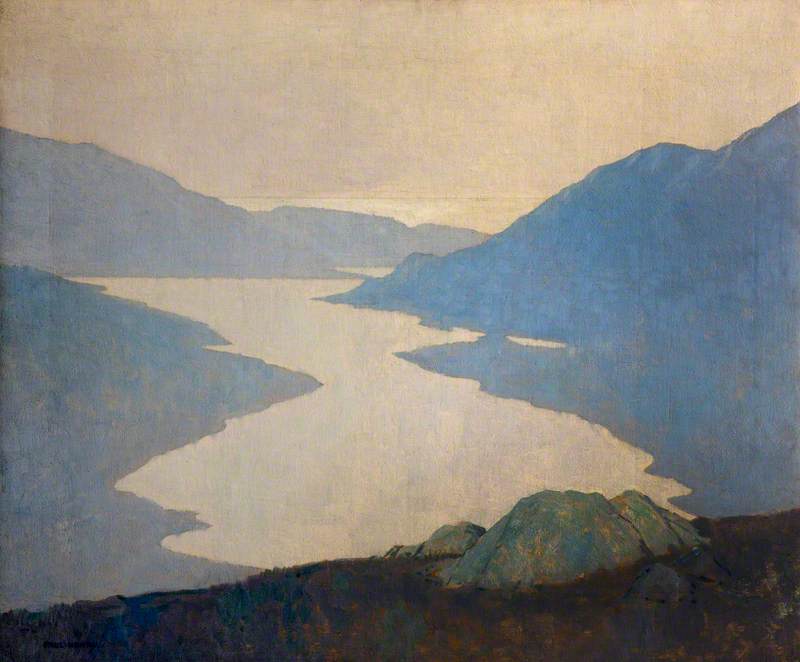

What can we learn about this earlier historical moment, more than a century and a half later? The UK Leave campaign (supported by the DUP) last year might have had 'take back control' as its slogan, and conjured up images of the white cliffs of Dover in its appeals to a nationalist 'British' landscape – but Northern Irish artists have spent the last couple of decades considering completely different conceptions of nature.

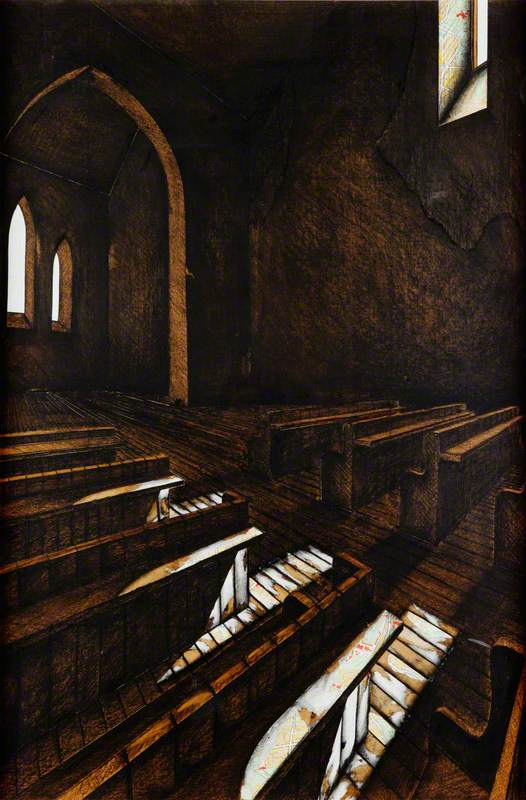

After the GFA, in particular, there was a sense of landscape not as (simply) bounteous and giving – but haunting and violent. Mary MacIntyre's photographic series A Contemporary Sublime, for example, plays self-consciously with a history of pastoral painting. Evoking both sunlit forests or gardens and bodies of water clogged with rubbish and detritus, as well as haunting Gothic fogs devouring a once sturdy-looking land, the series is saturated with a sense of anxiety.

In Willie Doherty's video works too, like Ghost Story, the trauma of the Troubles is described as a spectral flood entombed in the earth but beginning to seep out.

Ghost Story clip from Willie Doherty on Vimeo.

Similarly, Ursula Burke's porcelain sculpture Fáilte (Welcome) imagines the ground as sticky and liquid, cannibalising farmers and their chickens, churning them to a pulp.

If these artists tell us something, perhaps it is this: idealised images of the land are often used as an instrument to fuel militarism and mastery. At a time of Brexit talks, perhaps it is crucial to rethink how traditional ideas of landscape might give us a false sense of power and omnipotence. Recent Northern Irish art points to ways of being that lie beyond jingoistic fantasies, something needed now as much as ever.

Edwin Coomasaru, PhD candidate at The Courtauld Institute of Art, co-founder of the CHASE Gender, Sexuality & Violence Research Network, and Director of the International New Media Gallery