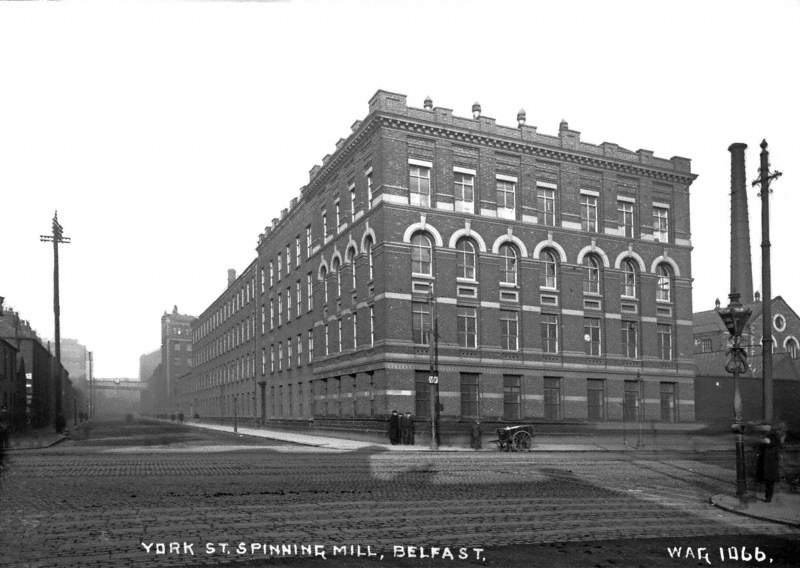

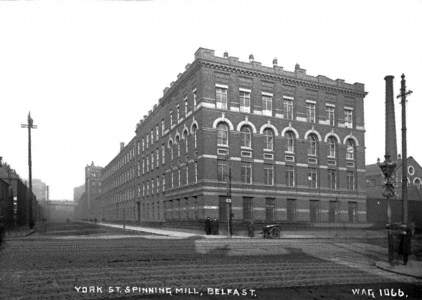

The years around 1910 arguably marked the peak of Belfast's industrial growth and achievement. In 1911 the city's population had trebled within the past fifty years, with 43,000 of its inhabitants employed, full-time and part-time, in the city's thriving linen industry.

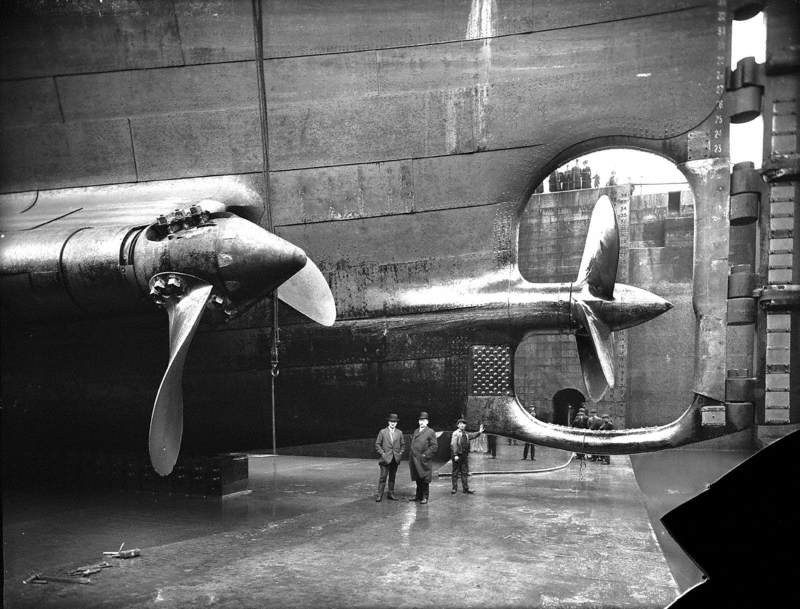

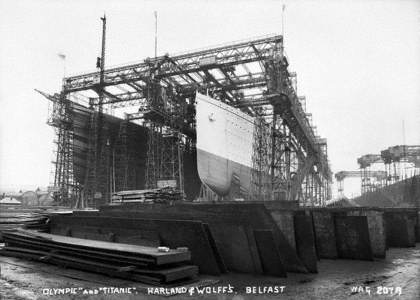

Between 1911 and 1912, the Harland and Wolff shipyard in Belfast completed the ocean liners RMS Olympic and RMS Titanic for the White Star Line.

'Olympic' and 'Titanic', Harland and Wolff's, Belfast

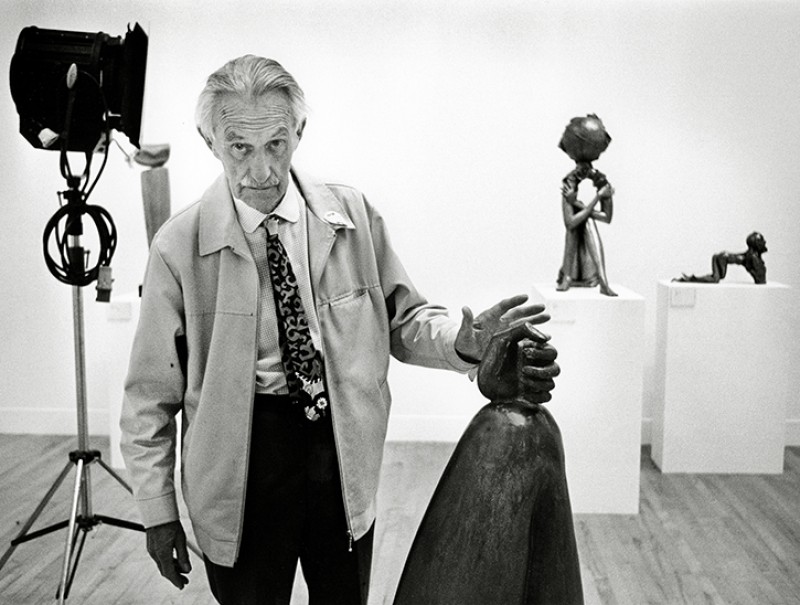

William Alfred Green (1870–1958)

Thanks to the city's prosperity, the average number of persons per dwelling had fallen to 4.81, having been 6.72 sixty years earlier.

The same period saw the birth of a group of artists who were to alter dynamically the visual documentation of the city in the period around the second world war. Colin Middleton, son of a damask designer, was born in 1910 and brought up on the slopes of Cavehill in north Belfast. The following year Nevill Johnson, who would move to Belfast in 1934 and become one of its most radically modernist artists, was born in England.

In 1916, Gerard Dillon was born just off the Falls Road in west Belfast, not far from where Daniel O'Neill, who was born in 1920, lived as a child. George Campbell was born in 1917 and only moved to Belfast after completing his schooling, but became closely connected with the city and with this group of painters.

Notably, none of these artists had a typical art school training. Most of them attended evening classes at the Belfast College of Art while holding down jobs or undertaking apprenticeships.

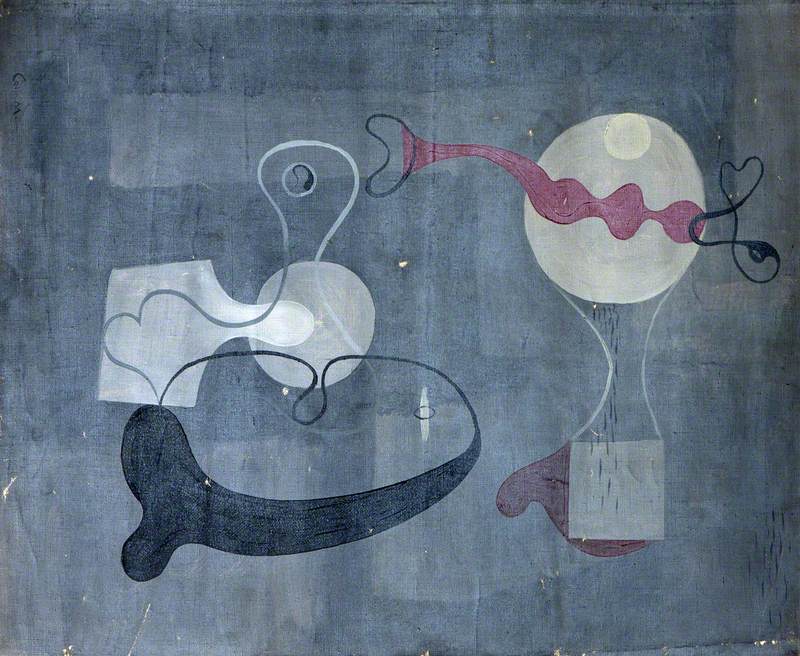

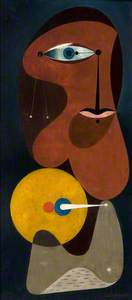

Colin Middleton, who had to abandon his ambitions to train in London at the Slade School due to his father's ill health, was the first to make his mark as an artist while still working full-time as a linen designer. The strikingly modernist nature of his work had been noted by John Hewitt in his review of the Ulster Academy of Arts annual exhibitions in the early 1930s, and it might have seemed a challenge to the conservative society of his home city.

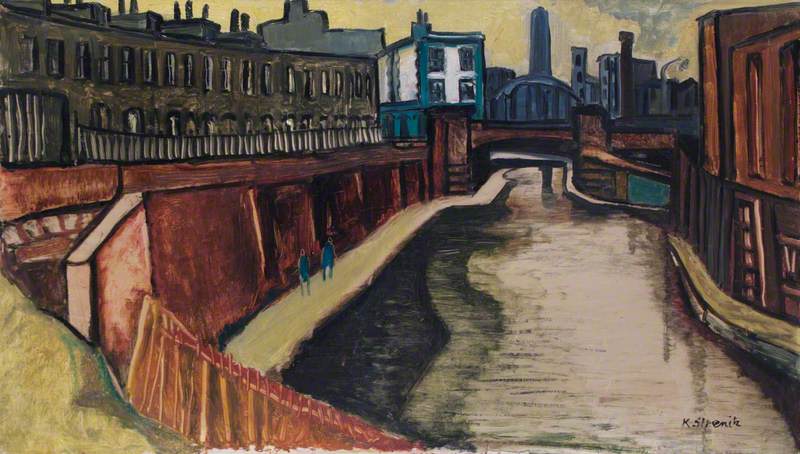

Middleton emerged from the substantial middle-class created by the success of industrial Belfast but his images of the city are the first truly modernist visual analysis of the experience of life in twentieth-century, urbanised Belfast.

The images of the city that Middleton created in the late 1930s are strikingly progressive in the context of painting in Northern Ireland at that time, shaped by his interest in surrealism and symbolism, but the alienation, angst and bleakness that is often present seems multi-layered and often a response to very personal events. As well as his father's death in 1935, his first wife, Maye, died shortly before the outbreak of war in 1939, after only four years of marriage.

Middleton's frustration at not being able to complete a more formal art education in London remained for some decades, despite the recognition he received as a painter and arguably it left an underlying antipathy to a city and an industry that he had wished to leave behind. His strong political beliefs aligned him with the workers rather than the managers and owners of Belfast's mills and factories.

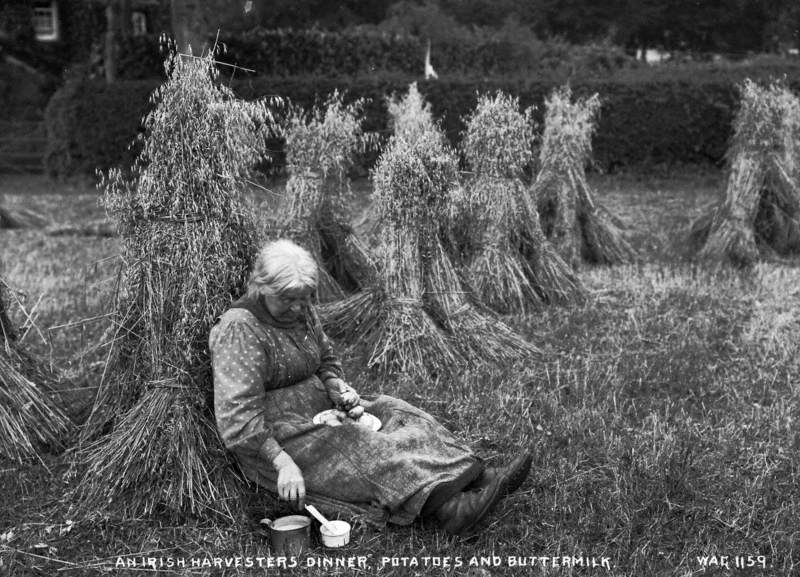

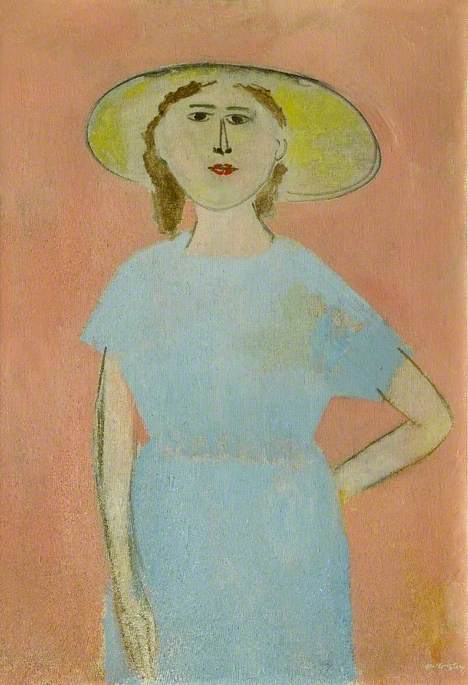

This empathy gradually becomes more evident during some of Middleton's wartime paintings. Rather like William Conor, who lived close to him on the Antrim Road, Middleton would stop to make discreet sketches on his cycle rides through the city, and his images of terraced streets and quiet corners, painted in the early years of the war, have a gentler mood and a more post-impressionistic style and are often peopled with isolated female figures.

One might see these women as an antithesis to the patriarchal society of industrial Belfast, becoming archetypes and embodiments of the places they inhabited and the lives lived there.

In 1947 Middleton eventually left the linen industry and his career as a designer behind and went to live and work at John Middleton Murry's community farm in England, in an attempt to be able to find more time to paint.

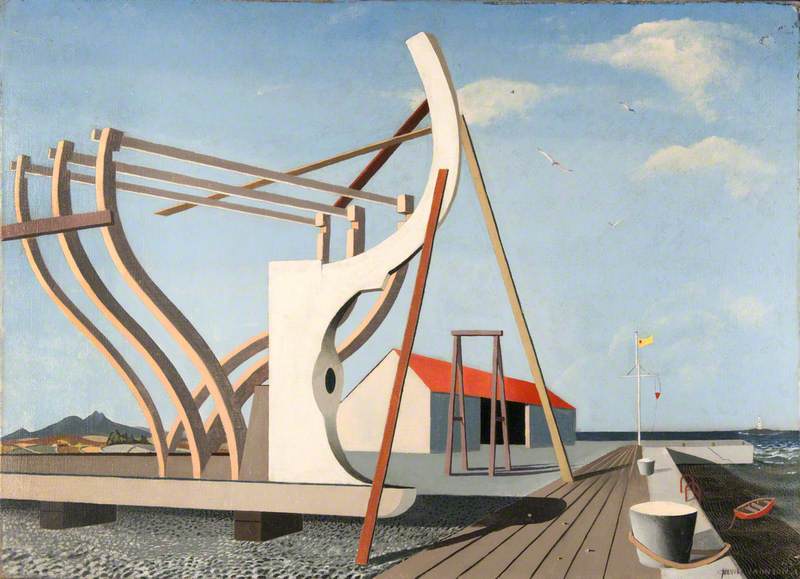

Nevill Johnson shared Middleton's political sympathies but figures rarely intrude into his earlier paintings. Again like Middleton, he tended towards pacificism and his post-war work is often overshadowed by the atomic threat. His painting in the 1940s is precise and highly finished, perhaps demonstrating the influence of his close friend John Luke. Johnson was untrained as an artist but had come to Belfast as a representative of the brake lining firm Ferodo and had quickly made connections amongst Belfast's small artistic community.

Kilkeel Shipyard conveys an initial sense of calm, although there is an unsettling surrealist mood conveyed in the incongruous industrial shapes of the shipyard and hinting at a darker underlying meaning that is almost at odds with the distant view of the Mournes.

This meaning is clarified in Johnson's autobiography The Other Side of Six, where he recalled enjoying a peaceful family picnic at Kilkeel on the day when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. Much of Johnson's other work in the 1940s was more overt in its criticism of the state and powerful institutions such as the Catholic Church.

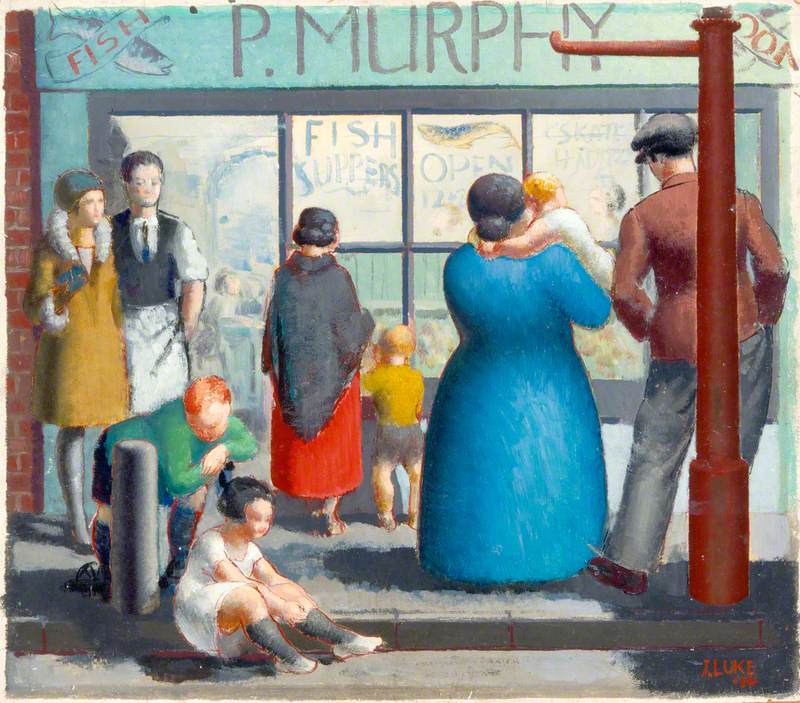

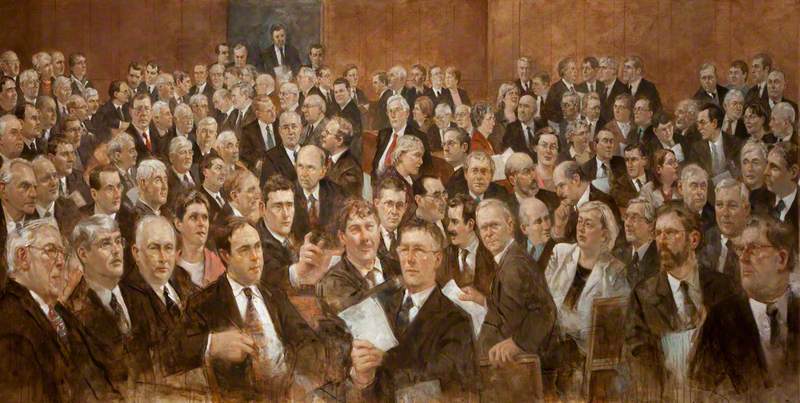

A slightly younger group of painters emerged in Belfast in the wartime years, mostly from working-class backgrounds and without significant formal training. Gerard Dillon was a house painter, and Daniel O'Neill had been an electrician, but they and their friend George Campbell were soon able to become full-time artists largely thanks to the patronage of the dealer Victor Waddington, whose gallery was in Dublin.

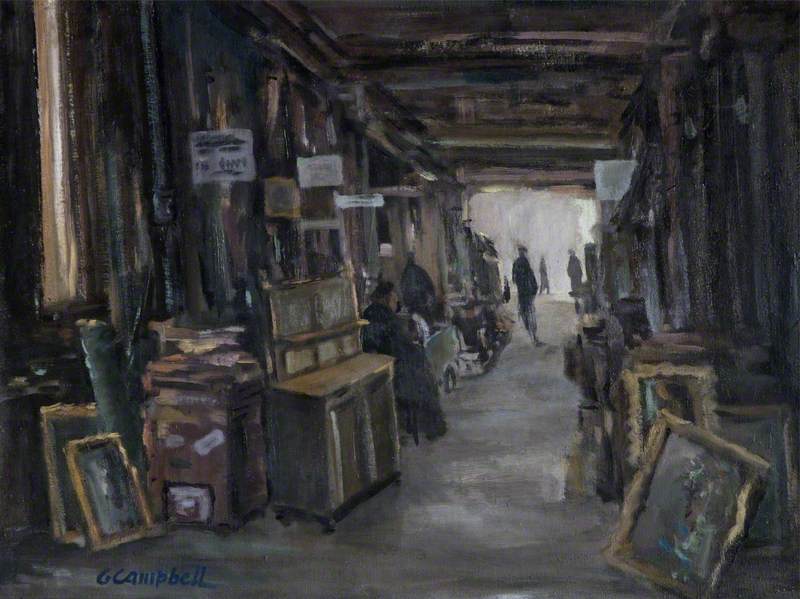

Increasingly at this time the art made in Belfast by its younger painters reflects the daily life of the city, the fish and chip shops, the cramped living quarters and the second-hand markets.

By the end of the war, contemporary artists had begun to assert a new visual identity for the city that emerged from their daily lives, rather than a grander, more formal vision of Belfast's imposing buildings and factories, or the wealthier life of the elite.

Interestingly, the emphasis on technical skill and creating objects that demonstrated a high level of training, which one might equate with the craftsmanship that had made Belfast such an industrial powerhouse, had arguably become less of a necessity for artists at this time. The Irish Times praised the virtues of the self-taught Dillon's attributes in the early 1940s, noting, as S. B. Kennedy writes, that 'despite his manifest lack of art-school training, he could "put the breath of life" into his painting', admiring 'his vivacity, his good colour sense and his ability to catch the essential movement of gesture to invoke drama'.

The voices of untrained artists coming from a range of backgrounds reflecting the full social diversity of Belfast, such as Dillon, Johnson, Markey Robinson and Daniel O'Neill, resulted in a very different vision of the city. These artists had also lived through the Great Depression and Second World War, and their art was not commercialised in many ways.

At certain times, largely for economic or practical reasons, they used unconventional materials and supports and their subject matter was entirely personal and drawn from their immediate environment, rather than responding to commissions or commercially popular subjects.

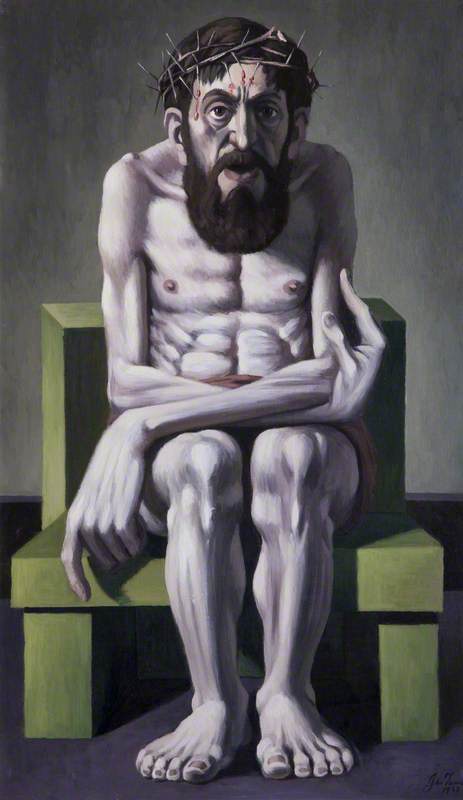

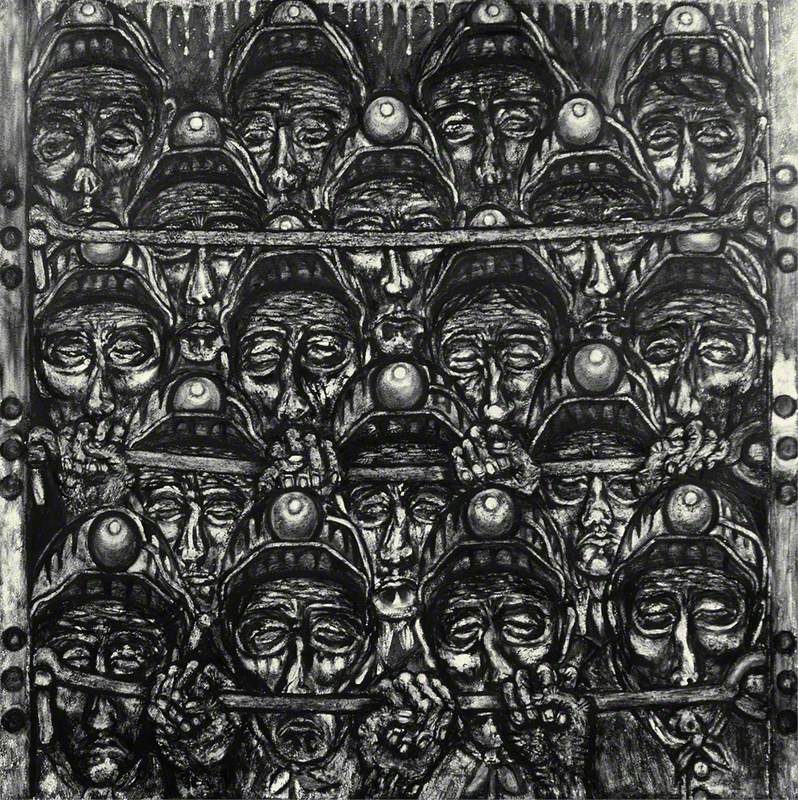

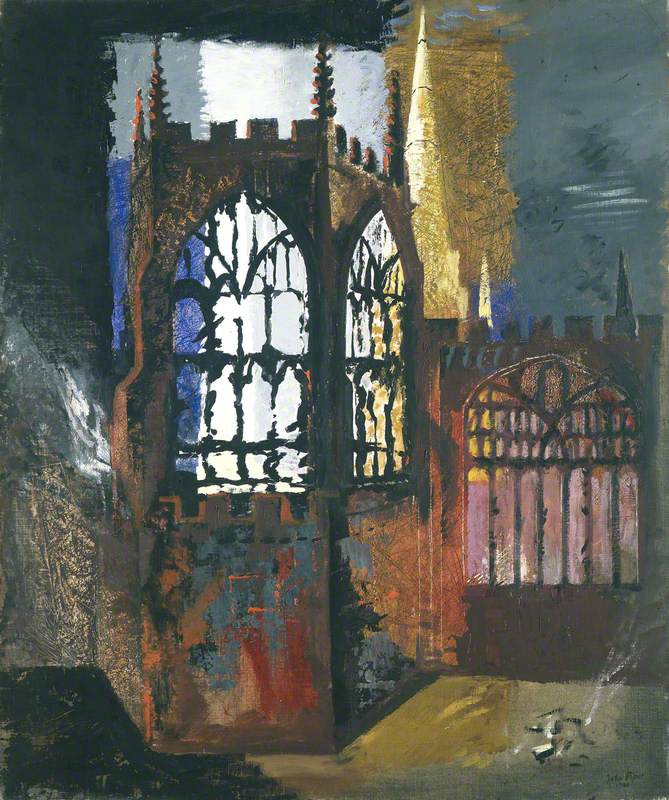

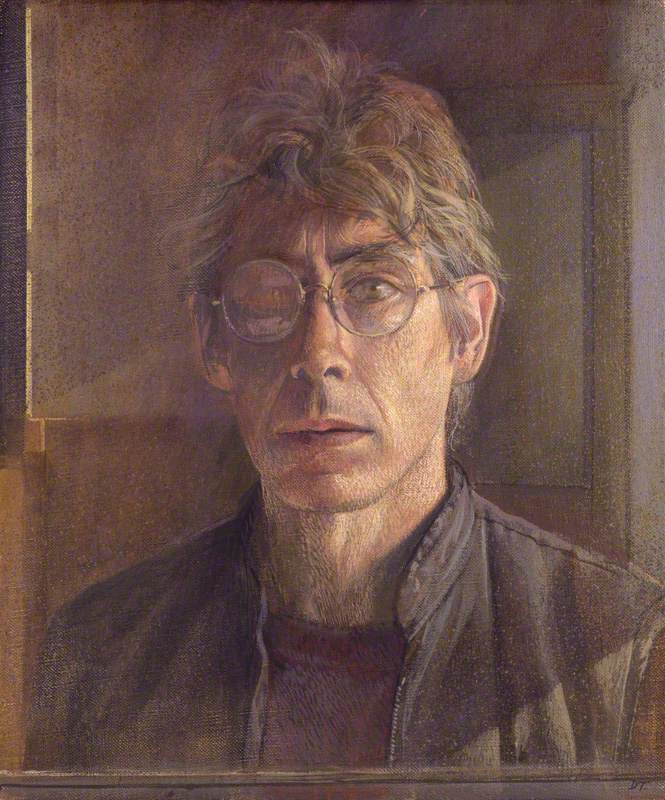

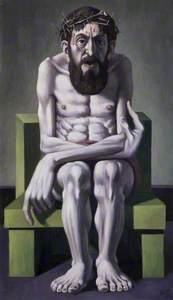

Middleton, Campbell and Dillon all painted and drew the city after the Blitz of 1941, and the new wartime iconography of crumbling buildings, blacked-out factories and ruined streets replaced that from earlier in the century, when so much of the building was new and constructed in response to Belfast's thriving industries. Their vision was at times darker, even if often tinged with romanticism. John Turner's Ecce Homo reflects a post-war mood in the city but also perhaps some self-doubt for artists facing a very different world.

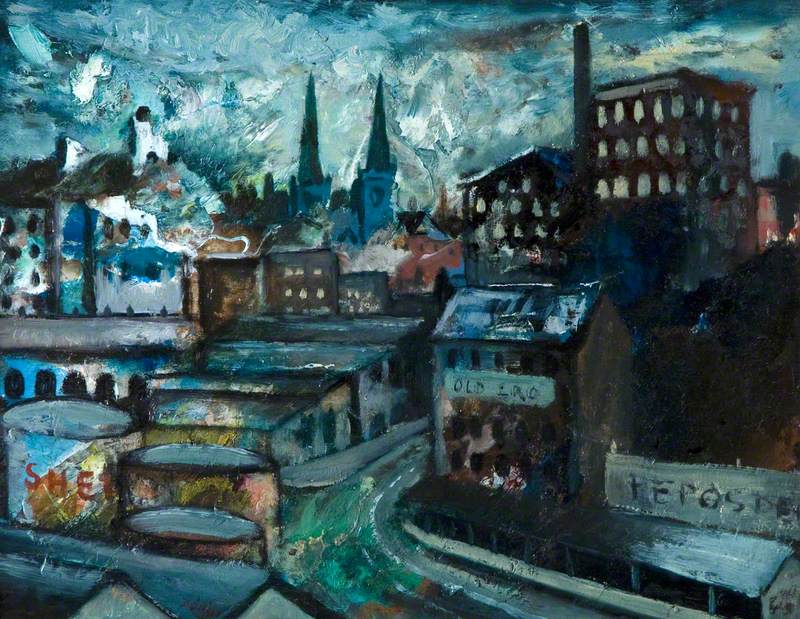

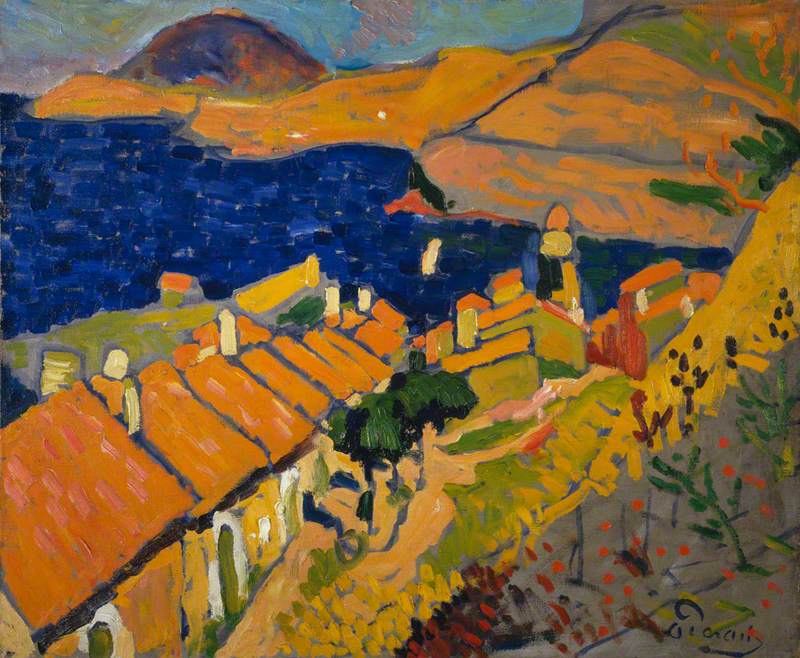

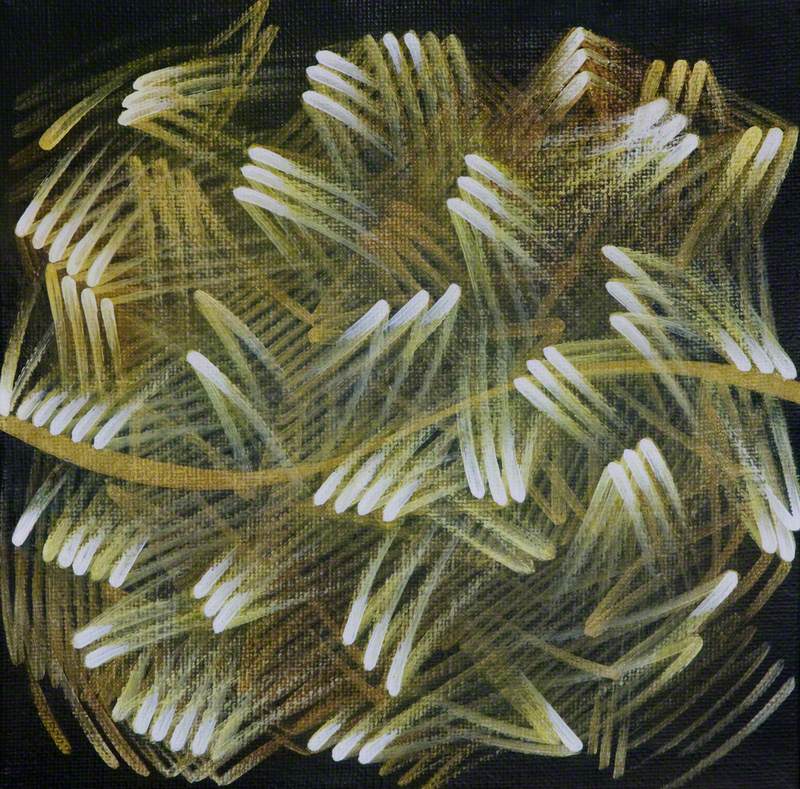

Daniel O'Neill's vision of the city is almost dreamlike although the factories, with windows still lit despite the darkness outside, tower over the houses and church steeples – its dramatic paint surface recalls Van Gogh and Vlaminck, and O'Neill typifies the interest of his generation in modern European art.

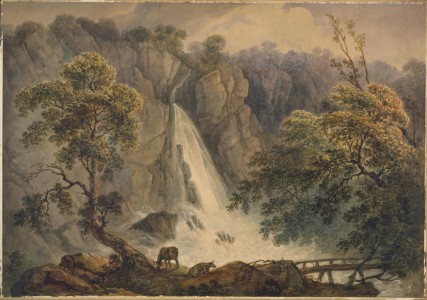

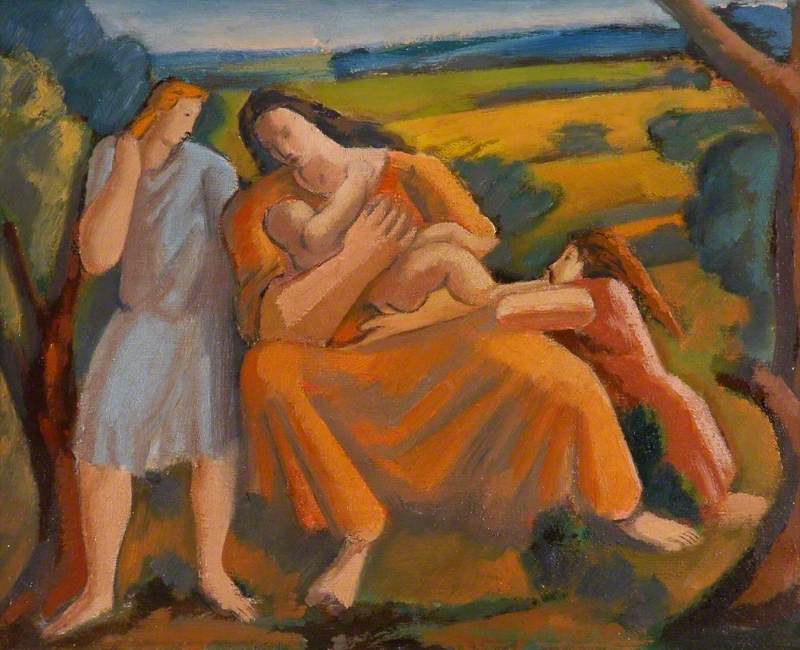

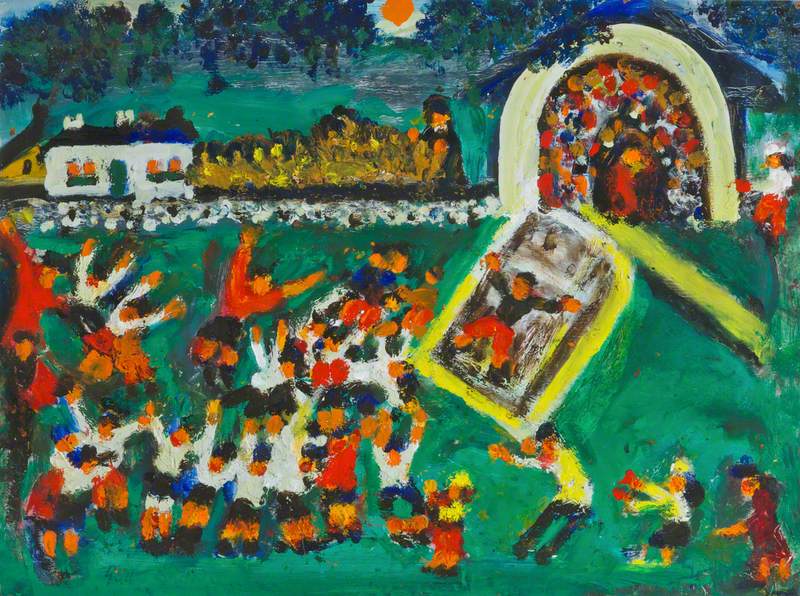

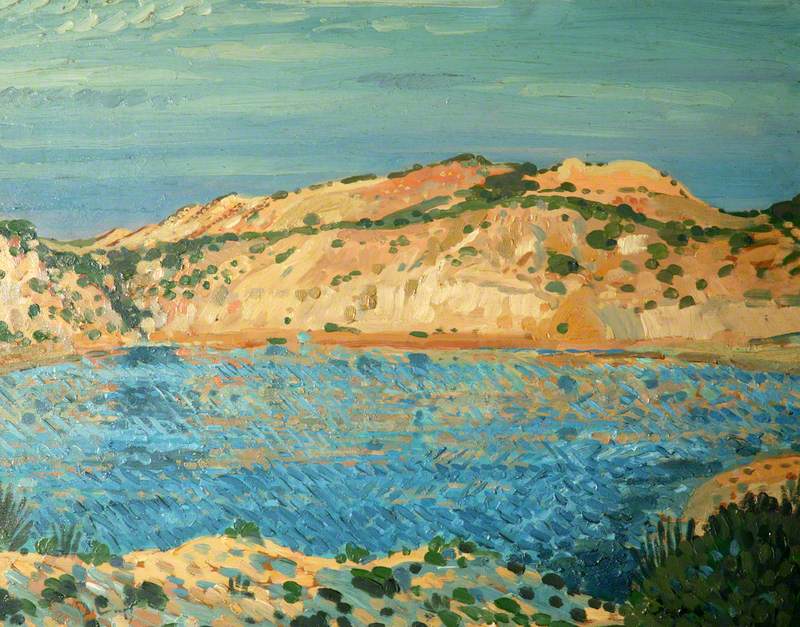

The rural idyll, often on the edge of the city, that had been depicted by artists such as Hans Iten or Humbert Craig is also less part of the experience of life for this generation. Middleton did paint the Cavehill, beside which he had grown up, but in general they sought a wilder and more distant landscape, with inhabitants whose way of life had been less affected by the developments of urbanisation and industrialisation.

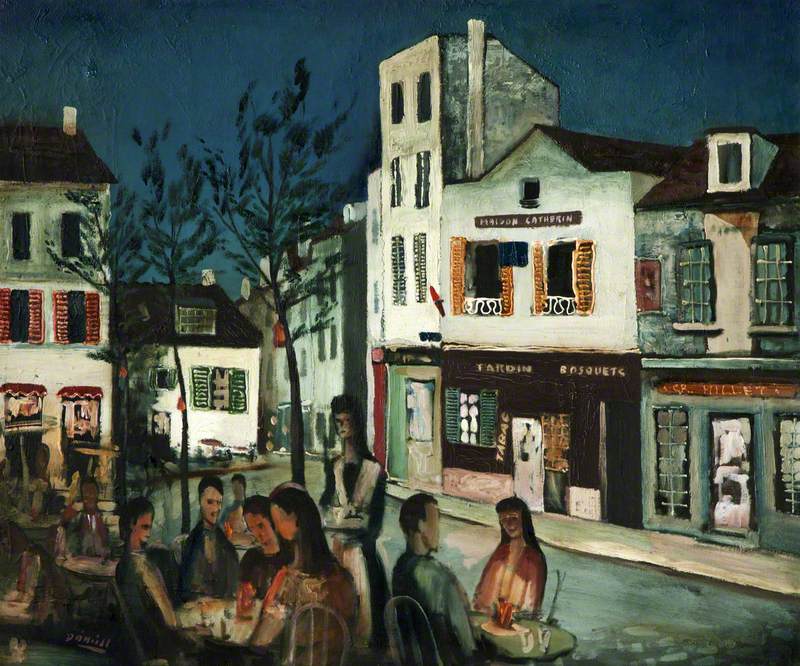

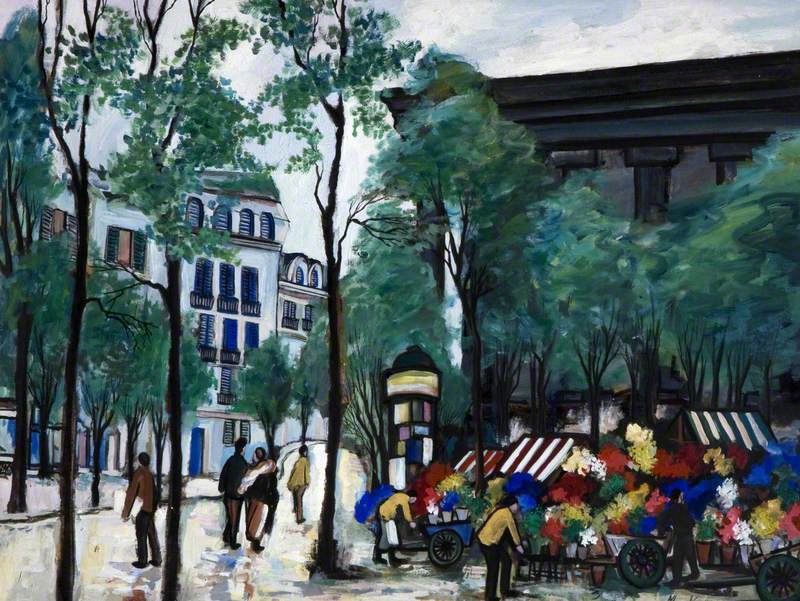

As with Dillon's images of the west of Ireland, O'Neill's painting of the Place du Tertre in Montmartre demonstrates how much this group of artists found their identity as artists beyond Northern Ireland, searching for social freedom as well as a different creative environment.

Markey Robinson also looked to Paris, while George Campbell became increasingly drawn to Spain and its landscape and way of life.

This internationalism and openness to European modernism, allied to an informality and directness in their manner of painting transformed painting in Northern Ireland in the mid-twentieth century. The subject matter they chose also presented a vision of a city that was less wealthy or confident than at its industrial peak. For Middleton and Johnson in particular, the subversive and unsettling style of surrealism and expressionism provided the means to more deeply examine the city around them as well as its relationship to its more vulnerable inhabitants.

Most of these artists left Belfast (and in some cases Northern Ireland) soon after the war, and it was only for a brief period that they had been working and exhibiting closely together in the city, but it remains a period in which the city and the visual response to it were radically altered.

Dickon Hall, art historian and Art UK Commissioning Editor (Northern Ireland)

This article was supported by Arts Council Northern Ireland

Further reading

Theo Snoddy, Dictionary of Irish Artists: Twentieth Century, Merlin, 2002

S. B. Kennedy, Irish Art and Modernism, Institute of Irish Studies, 1993