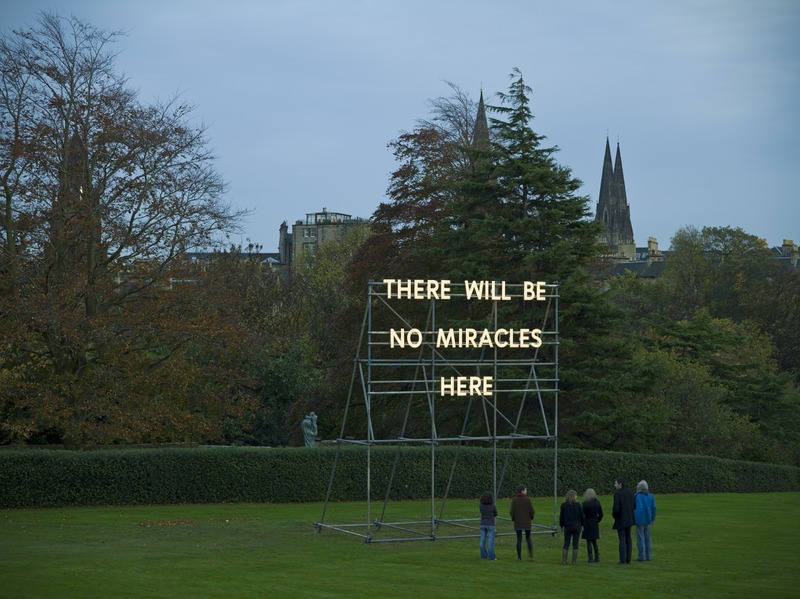

As you turn from Belford Road in Edinburgh into the National Galleries of Scotland: Modern, the neoclassical building with its palatial lawn opens out to a raking view across the city. Sitting on that lawn – facing the gallery building and all who approach it – a phrase in cool, white lights announces:

THERE WILL BE

NO MIRACLES

HERE

It is six metres high and six metres wide. The words loom over those who stand before them, adding to the sense of a pulpit proclamation. The contrast between the precision and form of the text and the scaffolding it sits on is stark. This looks decidedly temporary, as if it has been knocked up overnight and left there by persons unknown. What do these words mean and who is speaking? The statement is uncredited; its origin and intent are unknown. We are left to come to our own conclusions.

There Will Be No Miracles Here by Nathan Coley is a key sculpture in the story of contemporary art in Scotland. Coley is from the generation of artists, alongside Douglas Gordon, Christine Borland and Martin Boyce, among others, who emerged from Glasgow School of Art in the 1990s and completely shifted the power balance of Scottish contemporary art away from the institutional centres of Edinburgh to the vibrant, artist-driven scene of Glasgow.

Over the last 25 years, he has produced work that interrogates power and how it is exerted within society. Though working in a wide range of mediums, he is best known for his illuminated text works. Central to everything is the readymade – whether a phrase, an image, a tombstone – Coley uses existing material to conjure meaning that is often both immediate and intangible. The rich and shifting relationship between work and location is ever present.

Context can utterly transform the interpretation of his work in a way that can make viewing the same piece in two locations feel like completely different experiences.

The Lamp of Sacrifice, 286 Places of Worship, Edinburgh 2004

2004

Nathan Coley (b.1967)

Immediately behind There Will Be No Miracles Here are a great many of Edinburgh's religious buildings. Thinking about this alongside another well-known sculpture, Lamp of Sacrifice, 286 Places of Worship, Edinburgh 2004, which comprises cardboard models of every place of worship in the city, it highlights an important recurring theme.

Critiques of faith, dogma and the relationship between Church and State have featured throughout his career. Indeed, the phrase itself is taken from the seventeenth-century story of a French village, where reports of miraculous religious happenings had become so prevalent that a sign displaying a royal decree was erected, stating 'There will be no miracles here, by order of the King'. In Scotland's capital, the spires jostle for position with historic centres of political and military power, with Edinburgh Castle sitting atop the stramash of a view.

The Lamp of Sacrifice – 286 Places of Worship, Edinburgh (No. 9)

2004

Nathan Coley (b.1967)

The work has not always existed on this site and in this form though – this is just how it could be read now. In 2006, the same year that the sculpture was originally commissioned by Mount Stuart on the Isle of Bute, Coley was part of a group exhibition at the Bethlehem Peace Centre in the West Bank. Artists could send only a list of instructions as the safety of physical works could not be guaranteed.

There Will Be No Miracles Here

2006, holes in stone wall, installation at Bethlehem Peace Centre, Jerusalem by Nathan Coley (b.1967)

The Centre shares a square with the Mosque of Omar and the Church of Nativity; Coley sent his instructions for There Will Be No Miracles Here to be drilled into an external wall of the Centre. The conceptual, spiritual and political weight of this work still being in the West Bank in 2024 is extraordinary. It is a stark example of how the room for interpretation that the artist gives can instil entirely different feelings depending on where works are sited, and how that can also change as the world changes.

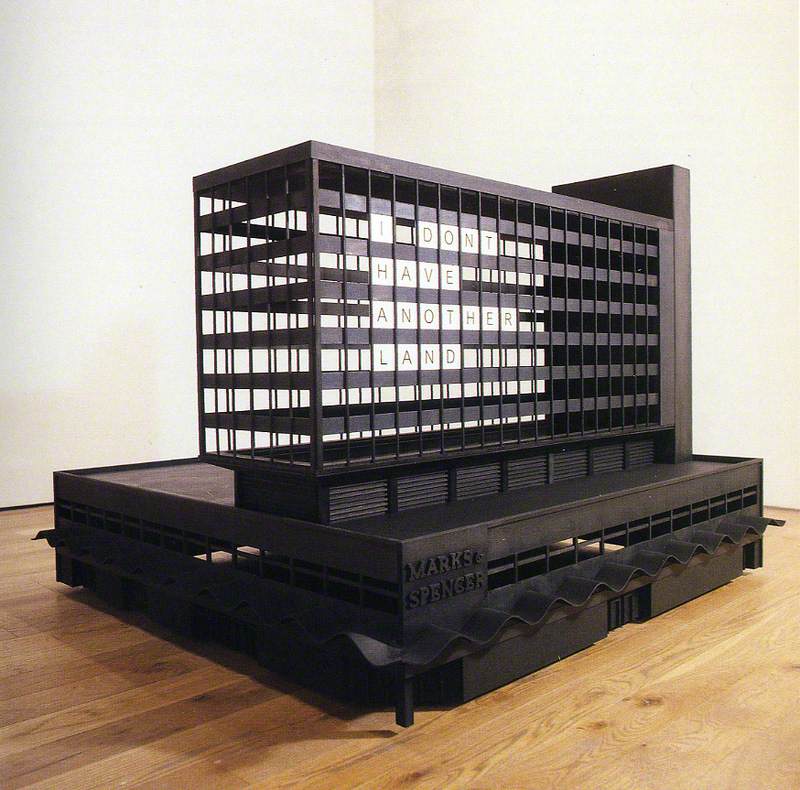

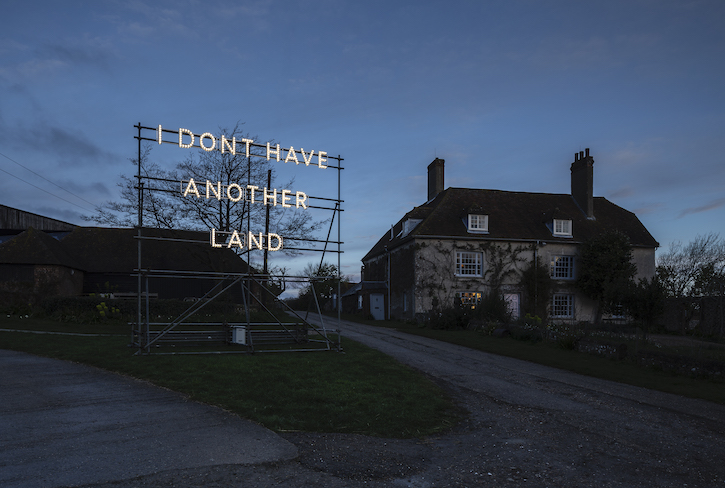

In the collection of The New Art Gallery Walsall sits an early work of Coley's that has similarly evolved across geographies and mediums. I Don't Have Another Land is an architectural model of Manchester's old Marks & Spencer building. This was severely damaged and then demolished following an IRA bomb planted in the city centre in 1996. The phrase is placed within the – seemingly – bombed-out windows of the structure, which is entirely black. Like other text works, the author and intent of the words are unknown, as is the implied connection between the text and the structure. This creates a subversive tension that is unsolvable. The slightly awkward syntax of the phrase is a subtle and powerful way to create pause and allow the ambiguity to seep in.

What is certain is that the words originated from an entirely different context. The artist saw some graffiti on a wall in Jerusalem during a visit to the city and here, as with the Bethlehem Peace Centre, it has a powerful resonance when placed in this geography. The words have since become a touchstone for a number of works in different forms and contexts.

I Don't Have Another Land

2022, illuminated text on scaffolding, installation at Charleston, Firle by Nathan Coley (b.1967)

Most recently, a major commission for Charleston in Lewes saw the creation of a new light sculpture I Don't Have Another Land for the grounds of the home and studio of artists Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant. The work can have many interpretations at this site. Duncan Grant's homosexuality – still very much illegal in the early twentieth century – could shape this work as a statement of defiance in the personal and creative haven that he and Bell made for themselves and others. We are also in twenty-first-century East Sussex, a part of South East England where refugees have been arriving, alive or dead, on small boats following the treacherous journey across the Channel. In the beautifully manicured gardens of Charleston, the graffiti in Jerusalem is perhaps closer to mind than first appears.

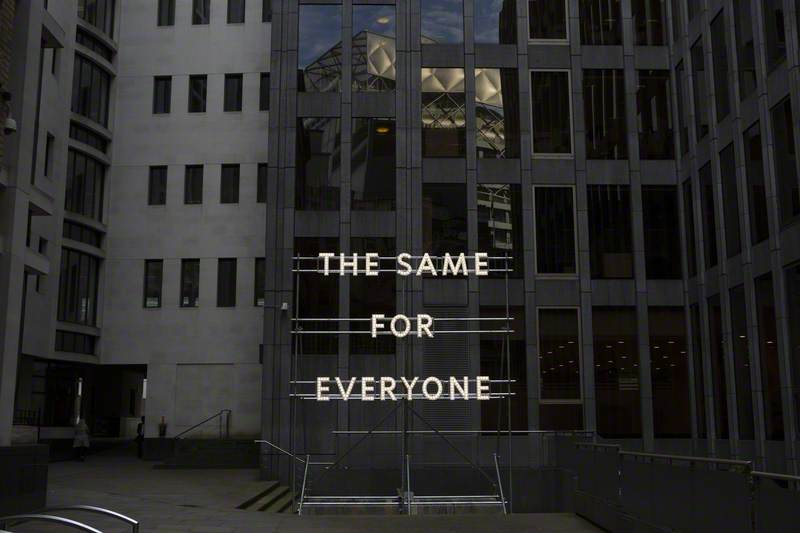

The Same For Everyone

2017, illuminated text on scaffolding, installed at Skive, Fiskerhuse by Nathan Coley (b.1967)

Ens fur Alle. Another informal message in a public space, this time in Denmark and in very different surroundings. Coley spotted a makeshift sign in Friland, a small eco-community, which celebrated the ethos of the village and wider Danish social, political and economic values – of egalitarianism, equality and fairness. Same for all.

Coley had been commissioned to produce one of the most ambitious projects of his career, creating a dozen light sculptures across the Jutland region to coincide with the European Capital of Culture programme in Aarhus. Instead of making 12 works, Coley produced one that would be displayed simultaneously at the chosen sites – a dozen identical light sculptures with the intricacies of local contexts making each unique. Coley drew on that Friland sign, creating The Same For Everyone.

A seemingly evangelical celebration of fairness and equality quickly dissolves when you ask yourself whether this is a statement, a question or an accusation. The phrase has the ring of chilling emptiness that many populist political campaign slogans seem to possess. Moreover, around the time the work was created, Oxfam produced a report which found that, for the first time, one per cent of the world's population had amassed more wealth than the remaining 99 per cent combined.

Taken out of its original context of Scandinavian ideals of fairness – whether real or imagined – this work showcases the humour that is often present in Coley's work: dry, mischievous and whip-smart. The Same For Everyone was part of the 9th Edition of Sculpture in the City, and sited in the heart of the financial district in the City of London. The irony of a phrase appropriated from an experimental eco-village in Denmark and landed outside the offices of major financial institutions in London is, for want of a better word, priceless.

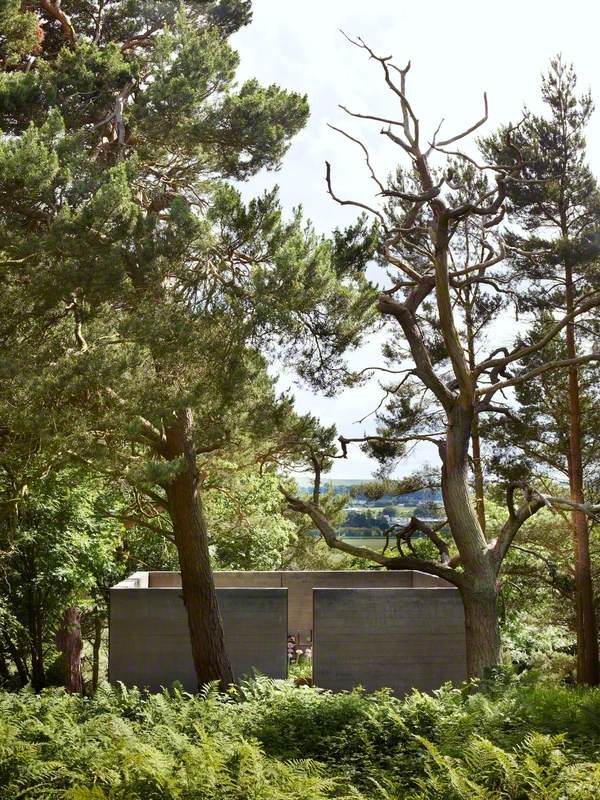

Back in Edinburgh, or its outskirts, and to conclude with something that certainly offers a level playing field for us all. Tucked into a quiet corner of the woods of Jupiter Artland is one of Coley's most extraordinary works, In Memory. The permanent commission is not a light sculpture, or an architectural model, but utilises the readymade all the same. As you approach, there is a high wall of austere concrete around the work which obscures what lies inside. The entrance through the wall is narrow – the exact width of the artist's shoulders – so you must enter alone. A small, well-kept graveyard lies inside. Headstones from different religious beliefs sit side by side, but the names of the dead have all been removed, chiselled from the smooth marble. Only the dates of birth, death and the commemorations remain on the headstones.

What has happened here? Who was 'a precious, father, brother and uncle', dead at 39? We will never know. Having entered alone, we are only left with our thoughts and the impact the space has on us as individuals. The erasure of the names is shocking in a way that is hard to resolve, yet there are any number of names that we could each place onto those headstones.

In all of Nathan Coley's works, the absence of a trusted narrator is absolutely crucial to the uneasy feeling his work often creates. We are commanded to act, or cease to act, to believe, or disbelieve, without knowing why, how or for what purpose. It means that we have no choice but to reflect our own politics, biases and experiences back onto the work. The meaning that we take from There Will Be No Miracles Here is the same as crossing the narrow threshold of In Memory: we are on our own.

Neil Lebeter, curator and writer

This content was supported by Creative Scotland