Dez Quarréll started Mythstories as a way of sharing his love of stories with the public.

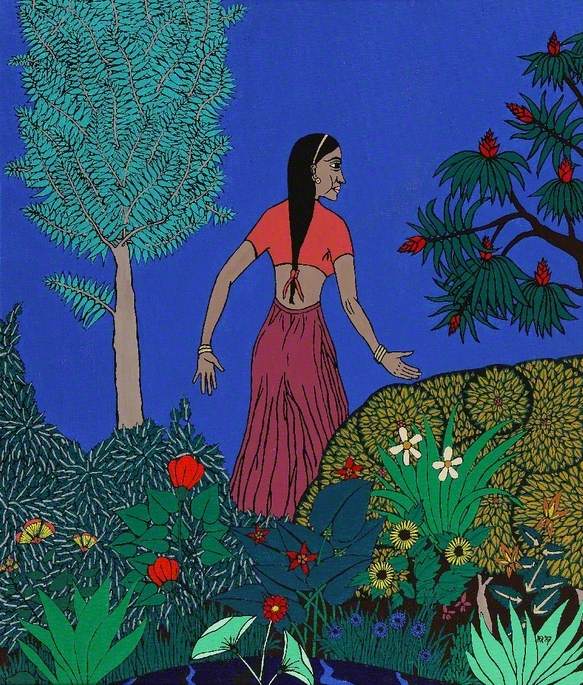

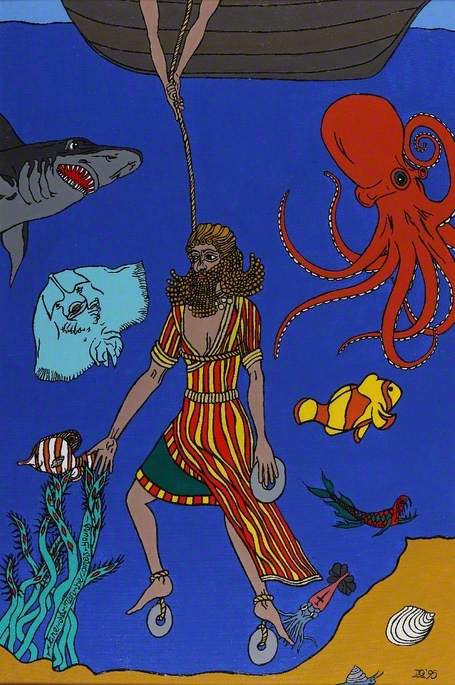

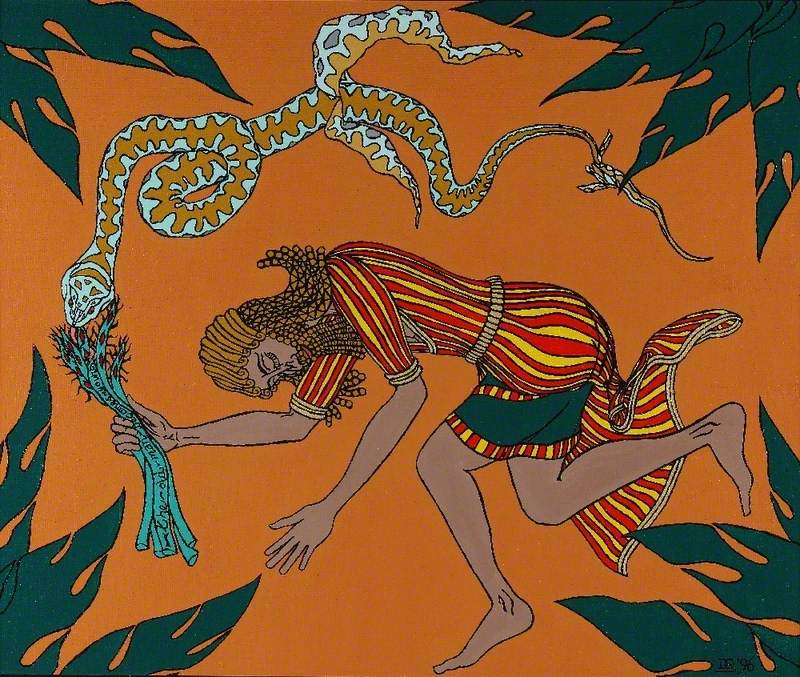

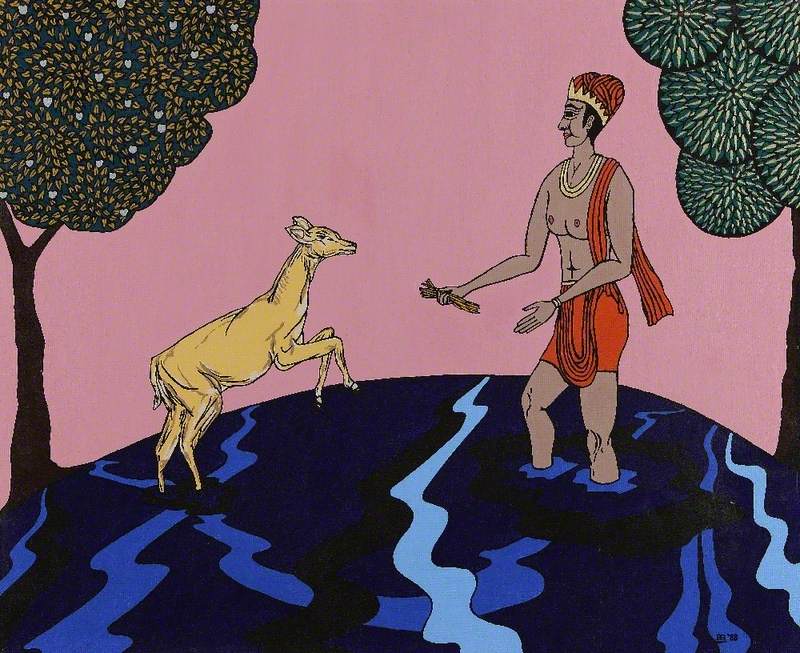

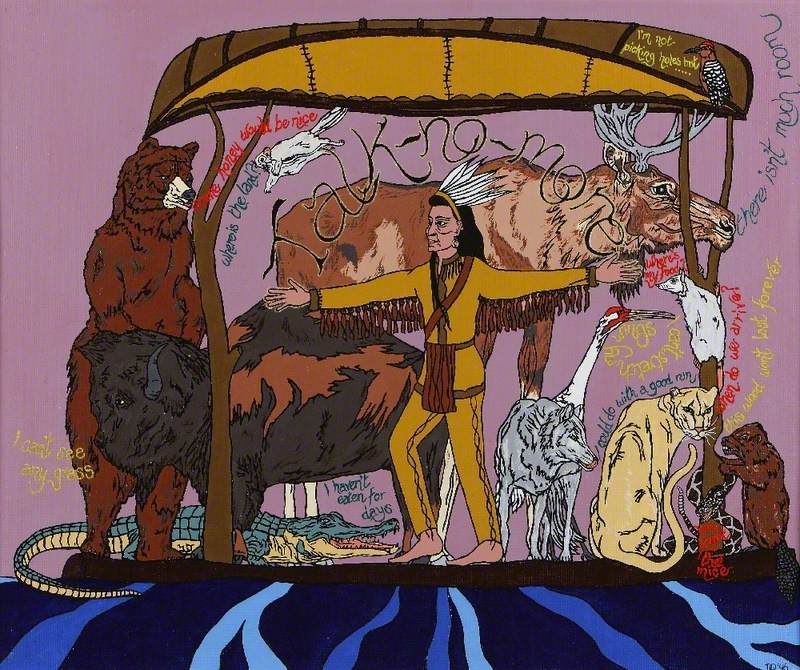

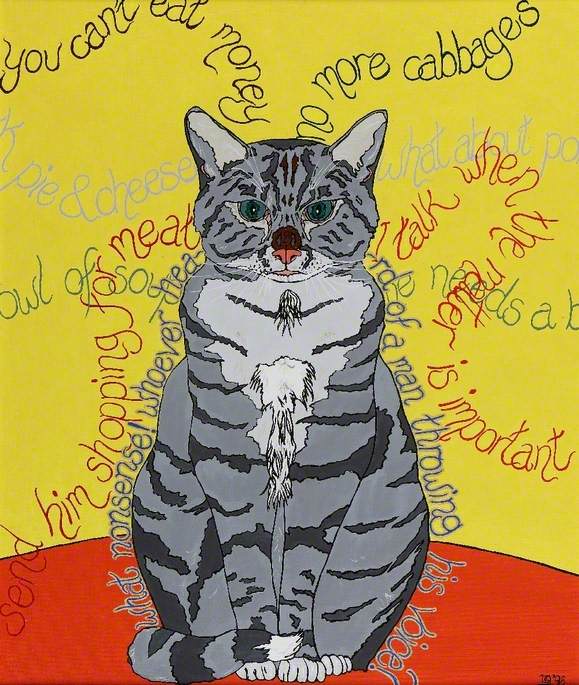

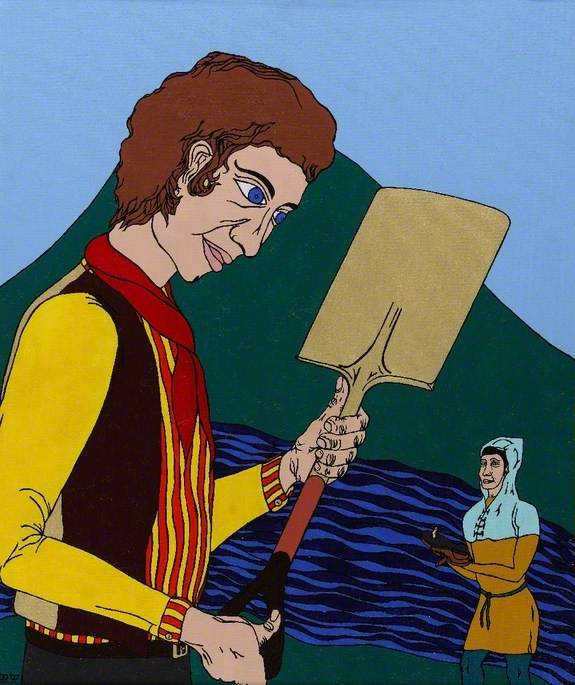

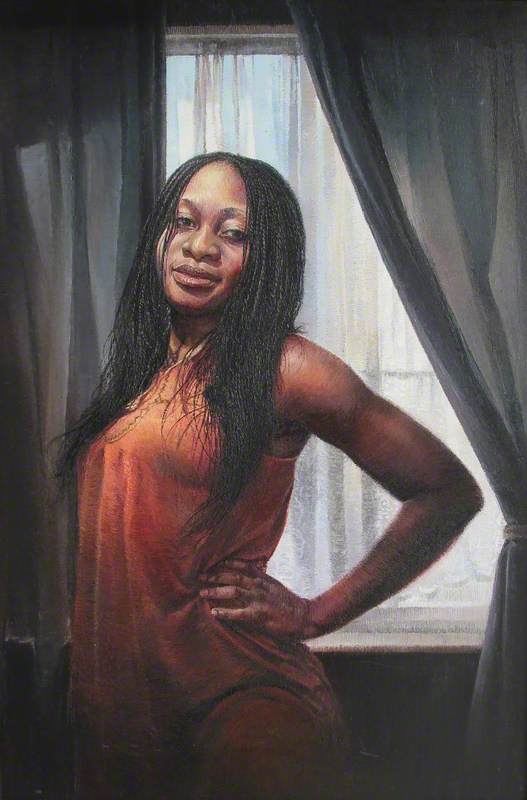

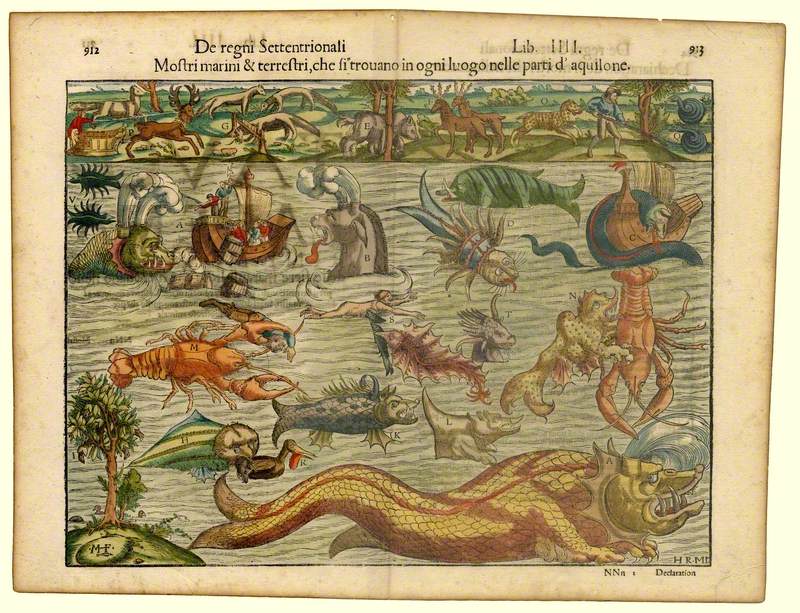

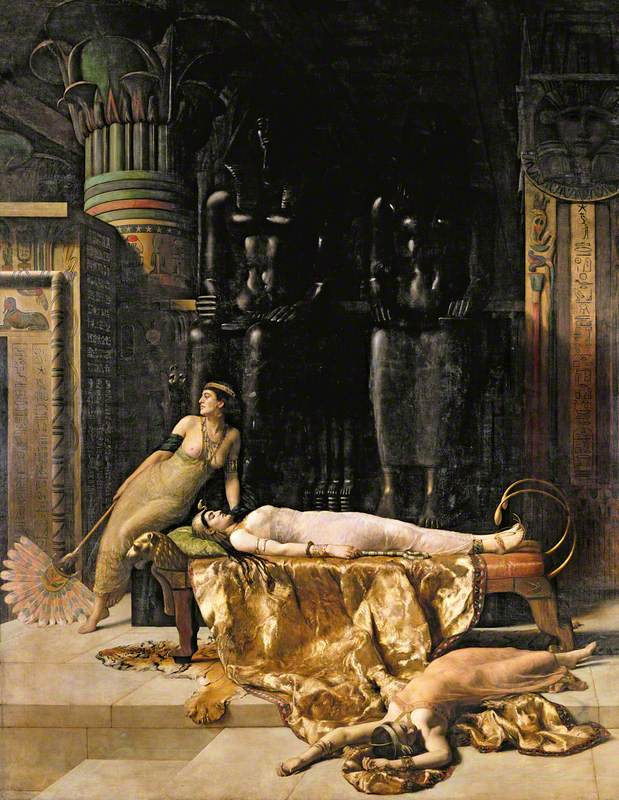

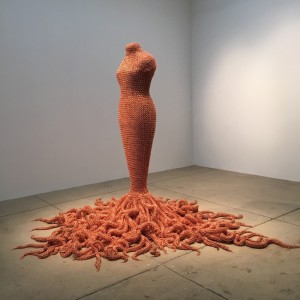

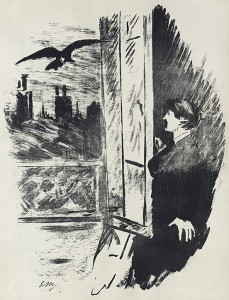

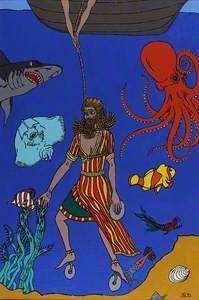

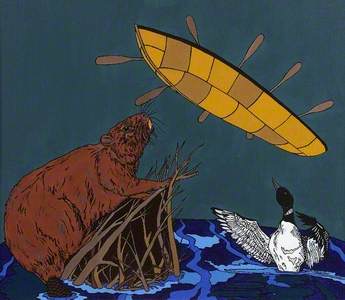

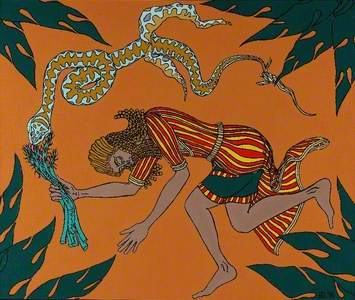

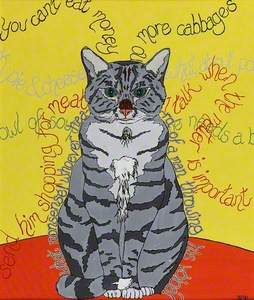

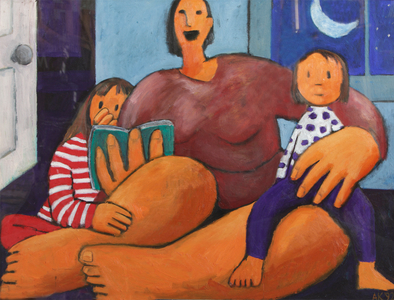

Operating in Shropshire, the museum invites people to come in and experience the tales Dez has collected. He represents them through his own paintings and other objects; each painting featured on this page encapsulates a whole story.

For National Storytelling Week, Art UK spoke to Dez about the collection at Mythstories, and how paintings can be the best way to keep stories alive.

How does it work when people visit Mythstories?

The first thing we do, when someone walks through the door, is explain a little of what we're all about, and I tell them a short story of one of the artefacts that are in the entrance hall. We tell them to go in, to pick things up, to touch things, because it's in picking up and manipulating some of these objects that the stories are revealed. We ready people for the fact that it's not like a normal museum: most of the objects are handling objects. Then we set them loose.

One of the stories, the Ramayan, is told by paintings, but it's also told by autometer, which moves the story on at the key moments. By turning the handle you see the movement at the crucial part of the story. The autometer are placed on Indian furniture, and inside the Indian furniture you'll find incense, dried lavender you can crush in your fingers and smell, clothes you can dress up in – all sorts of little artefacts. We try and appeal to all of the different senses to tell these stories in different ways.

We've got one exhibit where people can feel the story on clay tablets – that's the epic of Gilgamesh, which was found on clay tablets.

Where do the artworks that you've painted come into it?

It is the artworks that keep the stories alive – and in a very effective way.

Everyone's a storyteller in some respect. But what we're talking about is traditional narratives, and keeping them alive is a very difficult thing to do, because the only way you can do it is by telling the stories, and passing them on from tongue to ear.

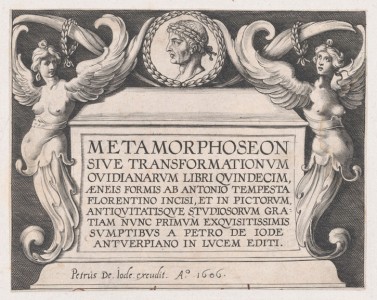

Our world has missed a blip and stopped telling a lot of the stories, so we have to rely on other media to find out more about them. While books are a good source of stories, they cloud the matter, because books are frozen words, and when they're published they come out as the author's idea of the story at a particular time.

So in a way, the best way of transmitting oral stories is through artworks. If you go back to people like Titian, they were the greatest storytellers because they were telling to a non-literate public, and they were conveying the story through their paintings, and making sure those bare bones of the story remain true – they were telling the story and keeping it alive.

So the paintings are useful as a jumping off point?

Absolutely, and they're a way to keep the story there. In storytelling, the key thing is that relationship between the teller and the audience. The way the storyteller tells the story will vary with every individual audience that they tell it to, because everyone receives things in a different way.

A storyteller is trying to paint a picture of a story, but if he tells the story to ten people, the picture in each of those people's minds will be different. I suppose our artworks are an encapsulation of those important parts of the story that remain unchanged, despite updating the story for new ears and new times.

The images free the story and allow the interpretation to go forward, and allow it to be seen by the eyes of someone with completely different experiences. Although a story is only really there when it's out in the air being told, and it's between two people, the teller and the listener.

A lot of the stories are from India, and Native America, and Canada. How did you come to find out about these?

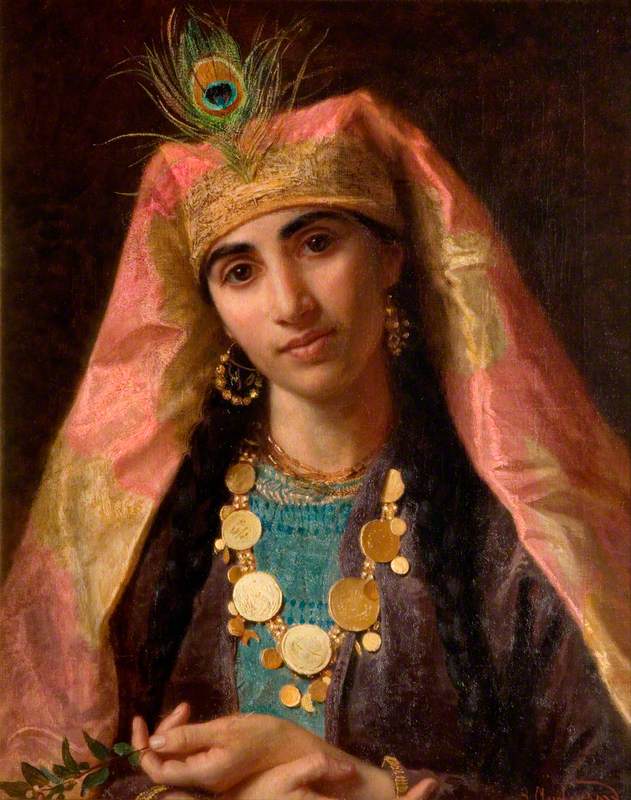

When I was seven or eight, I had a teacher in primary school who was Anglo-Indian, and she used to tell me traditional Indian stories if I'd stay behind and wash the brushes and glues. So consequently I was always finding some excuse to stay behind after school and listen to her tell these stories. They wouldn't normally have been told in school but they were from her background... and very willingly she told them, and they stuck with me all my life.

As a fine artist, the first things I concentrated on were those Indian stories. I suppose every artist goes to every canvas with a story in their mind. I just go looking for stories wherever I can find them. I visited Canada and fell in love with it, and so went hell for leather to find Canadian stories I could connect with! There are a selection of Shropshire stories too – that's where I was living at the time and that's where the museum still is.

Is Mythstories still expanding and tell more stories?

Definitely, yes. All of the time we're looking for new old stories, so to speak.

Making those stories ready again for the audience – that's what we do. Everything goes back to that love of stories that you pick up at some point in your life, and that ignition. It lit mine good and strong, and I've got a real, real love of stories and their transmission, and art is the best way to do it.

Pictures and three-dimensional creations, like sculpture, they're particularly wonderful conduits for stories, and for the essence of stories: they don't get in the way too much, they don't give you too much detail. They give you an idea of what the characters might look like, but the things that really seep in are the situations that people are in. I am a great lover of classical art and modern art, but you ask me to put a face to people at The Last Supper, and I can't. But I can remember all the positions and what they're doing, how they're moving the food down the table, all of those things. Leda and the Swan, that beautiful painting in The National Gallery, you can't remember exactly what the faces look like, but you can remember that visceral image.

Which are your personal favourite stories?

If I had to choose, I think I'd go back to the Canadian stories, and particularly those told by a man called Michel Meloche. He was a storyteller in Quebec, in late Victorian times. His great-great-niece, Natalie Savage Carlson, wrote a book called The Talking Cat and Other Stories of French Canada and in that, she told those stories which Meloche used to tell to the other villagers up in Quebec, while leaning against his mantelpiece in his kitchen. He'd tap out his pipe on the coal scuttle, and then he'd begin. And he'd do a spot of clog dancing, and squeezebox playing, and he'd entertain on those long dark nights.

I also keep coming back to the stories of the Wrekin, and the Wrekin Giant (or Giants, depending on which versions of the story you go for). There's so many of them, and the more you go into it the more you find.

I think, basically, all stories are important things in the world. Stories were being told as civilisation started, in pictorial ways long before they were put down into words. The one thing I keep coming back to is that stories are in us all, no matter colour of skin, no matter what race or creed we are, stories are the glue that binds us all together, with their commonality, just like bones. We all have bones, we all have stories, and they belong to all of us.

Molly Tresadern, Art UK Content Creator and Marketer

You can read or listen to the stories behind Dez's paintings on the Mythstories site

You can buy prints of Dez's paintings on the Art UK Shop