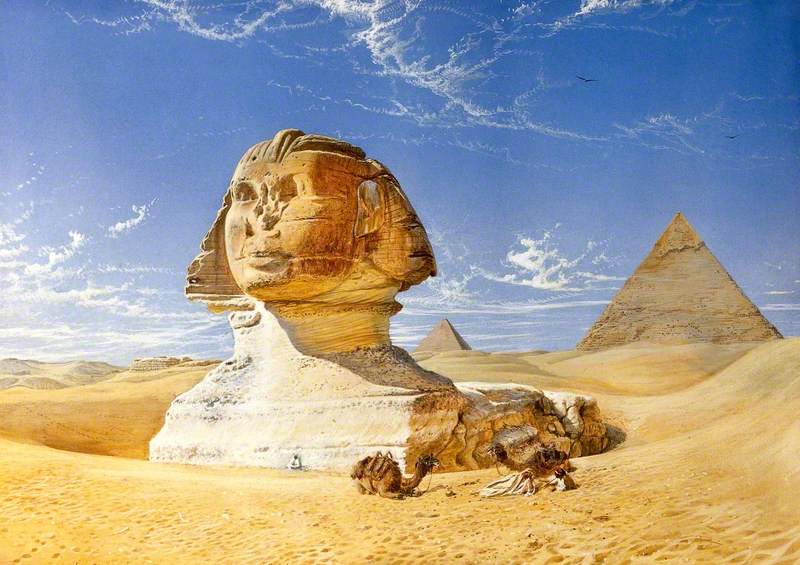

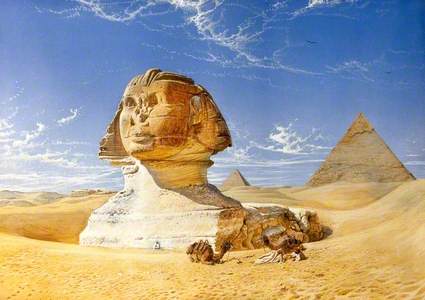

Spanning over 3,000 years, the incredible civilisation of ancient Egyptian has enthralled explorers and the general populace alike for centuries. The historical othering and consequent mysticism of the great African power enhanced the collective fascination – the ancient Egyptian world appearing to be so unlike the West's 'true' ancestors of antiquity, the Greeks and Romans, despite the trio's vast cultural exchange and similarities.

Modern Egyptology – the study of Egypt – began with the invasion of Egypt by Napoleon at the turn of the nineteenth century. The discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799 and its subsequent use in deciphering hieroglyphs by Jean-François Champollion breathed new life into the discipline that had previously primarily focused on monuments such as the Great Sphinx and the pyramids rather than deciphering text or visual culture.

Napoléon Bonaparte (Buonaparté Leaving Egypt)

1800

James Gillray (1756–1815)

Myrtle Florence Broome (1888–1978) was one of many British Egyptologists who contributed to the exploration of ancient Egyptian culture. Born in Muswell Hill in London, Broome lived most of her life and trained as an artist in Bushey, now home to the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery which was once the Broomes' family home.

Broome went on to obtain a Certificate in Egyptology under eminent archaeologists Sir Flinders Petrie and Margaret Murray, the former going on to sell his large collection of Egyptian antiquities to University College London which now form the Petrie Museum.

In 1929, Broome was selected to assist Canadian epigrapher Amice Calverley in recording the wall scenes in the Temple of Seti I, dating to around 1300 BC, at Abydos.

#TBT to an archival photo of the Temple of Seti I in Abydos, where we see a relief of Seti standing between Isis and Ra. On the bottom left is Isis presenting life to Seti, and on the bottom right is Seti before Horus, who is wearing the crown of Thoth. pic.twitter.com/PBhCXJOmt2

— Oriental Institute (@orientalinst) May 27, 2021

Work originally commissioned by the Egypt Exploration Society, the project was ultimately financed by the philanthropic Rockefeller family after John Rockefeller Jr was so impressed by the duo's photographic-like reproductions. Rockefeller's patronage of the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago brought in further funding and support.

Broome formally became Calverley's assistant and the two women were responsible for all the paintings and replications of the temple, with the help of a small staff of artists. The duo used various methods to accurately capture the temple over the next eight years. The drawings were eventually published in four elephant folio-sized volumes.

Discover the life & art of Egyptologist Amice Calverley in our new exhibit "From Oakville to Abydos" opening Oct 23! pic.twitter.com/I7EtWpIIPy

— Oakville Museum (@Oakville_Museum) October 22, 2015

Much of the recording was done using photography which the artists then went over with pencil. A camera lucida was sometimes used to draw the outlines of the structure to help accurately render perspective. And a number of watercolour copies were also made as colour photography was still a relatively new invention.

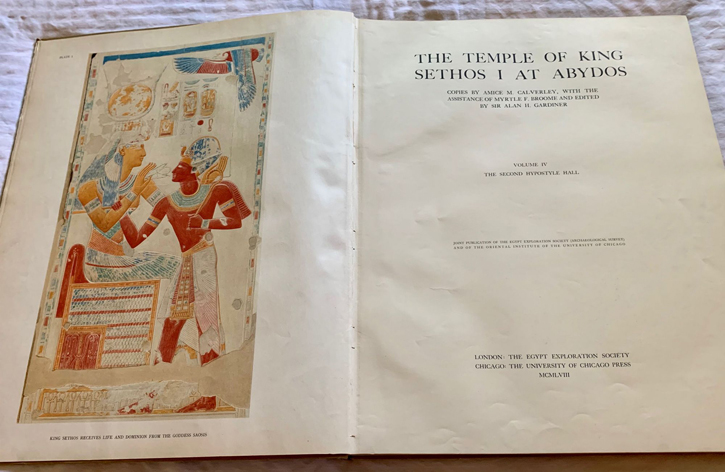

Title page and frontispiece of 'The Temple of Sethos I at Abydos'

Volume IV, The Second Hypostyle Hall, copied by Amice M. Calverley, with the assistance of Myrtle F. Broome, and edited by Alan H. Gardiner

Of their work, Professor James H. Breasted of the University of Chicago said the following: 'It is difficult to say too much in praise of the magnificent work... No better draftsmanship has ever been available in the service of archaeology... [indeed] the question may be fairly raised whether any drawing as good as this has ever before been done in Egypt.'

Perhaps you prefer something a little more regal? How about Vol II of the huge folio edition of Calverley and Broome’s work at the temple of Seti I at Abydos? lot 63. https://t.co/k2p5YZcdih #BIGfundraiser pic.twitter.com/N5NR1nqU4v

— The Egypt Exploration Society (@TheEES) June 3, 2019

The work was incredibly tedious and demanded intense concentration but no creative freedom. At least one of the artists who joined the team was reduced to a nervous breakdown due to the nature of the work. Of her work, Broome remarked in one of her many letters to her parents: 'I am enjoying the work here very much and getting into the way of it. I have never seen so much delicate detail in any place before, it needs most accurate and careful copying. Each tiny hieroglyph is in itself a perfect picture.'

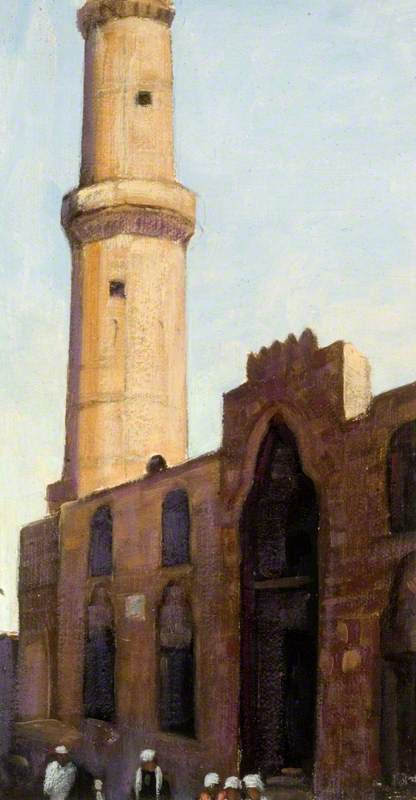

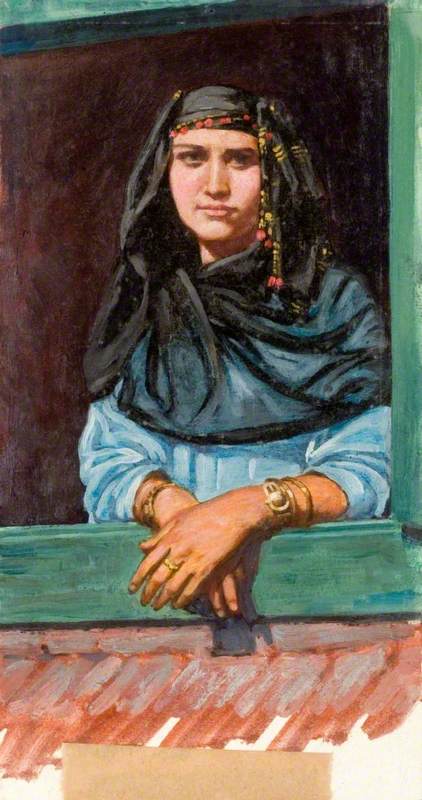

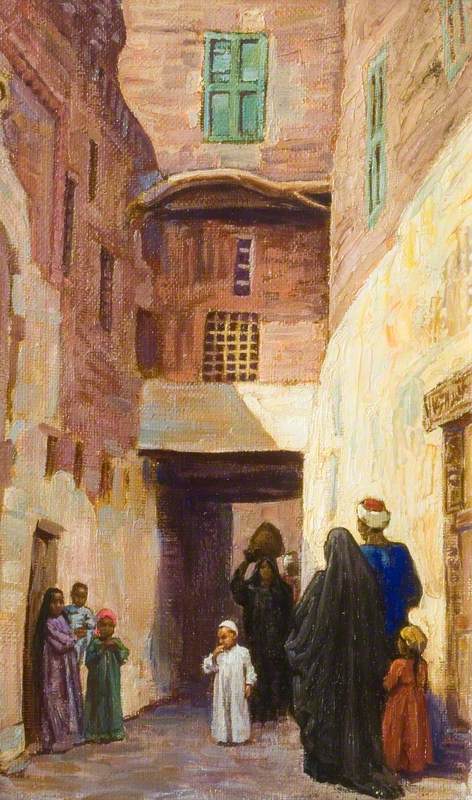

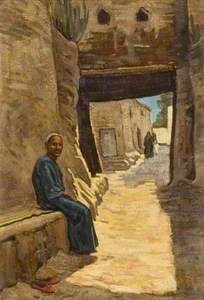

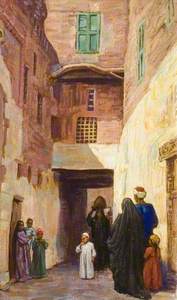

Broome's incredible letters – now housed at the Griffith Institute in Oxford – capture in vivid detail life in Egypt in the 1930s from the traditions of the local people to the work of artisans.

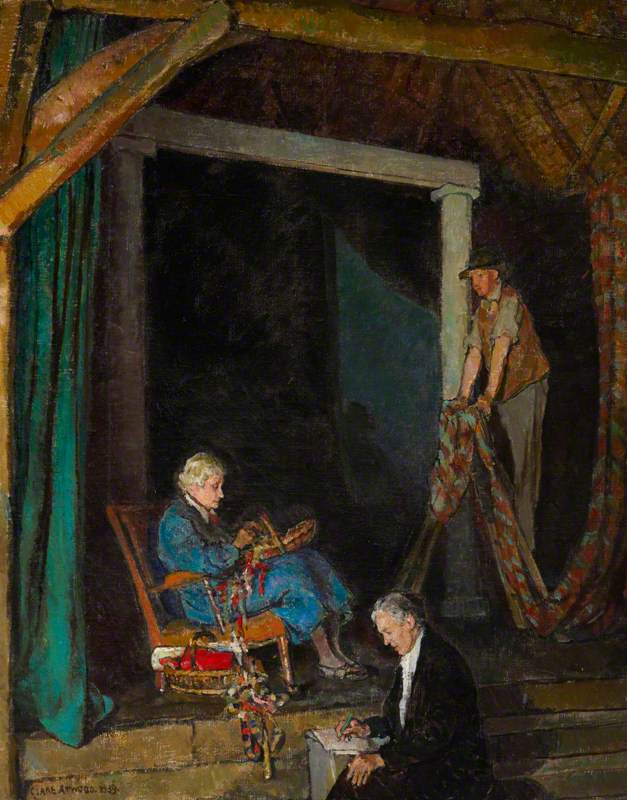

Drawing of an Arab Child in a Doorway of a Brick Building

Myrtle Florence Broome (1888–1978)

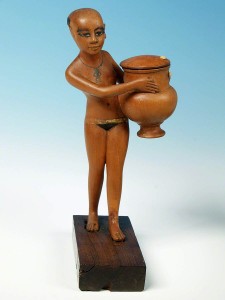

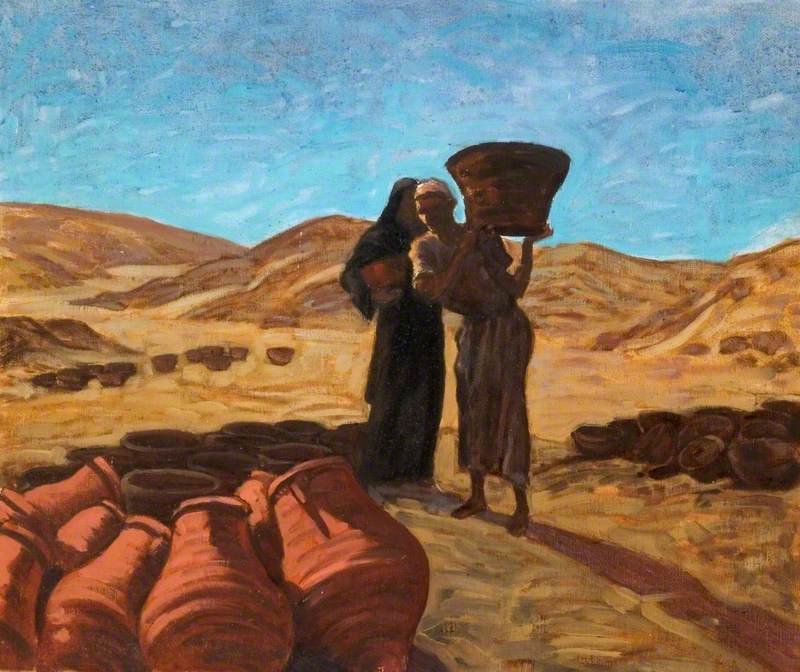

Egyptian Man and Woman Holding Earthenware Vessels

Myrtle Florence Broome (1888–1978)

They also describe the pair's living conditions and what it was like to be English, working women living abroad in a post-war world.

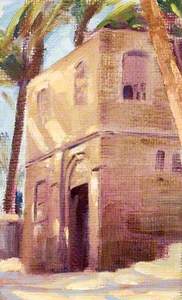

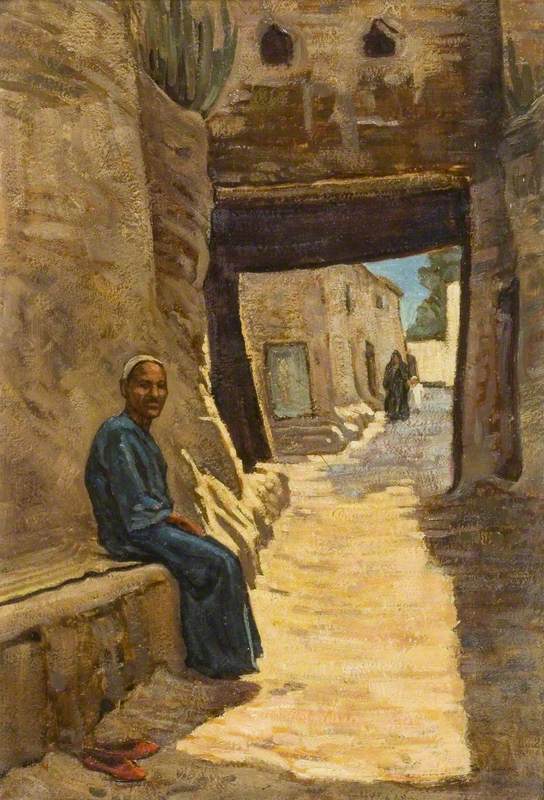

A Man Seated in an Egyptian Village Street

Myrtle Florence Broome (1888–1978)

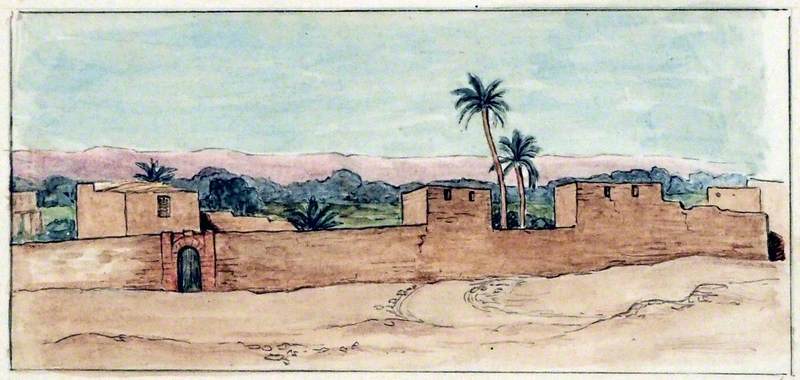

Calverley and Broome fully embraced the frugal lifestyle, living together in a rudimentary mudbrick house near the temple with two local servants. Broome even remarked in one letter her indignation that an accompanying artist would expect meat every day.

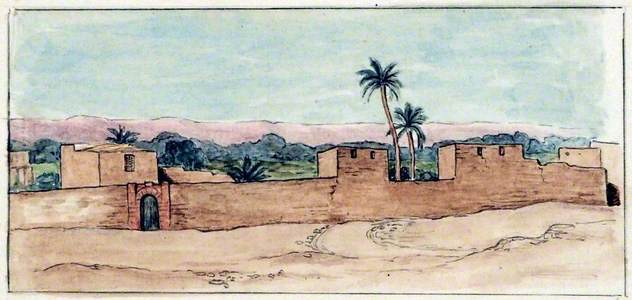

Egyptian Family in an Oasis Village

Myrtle Florence Broome (1888–1978)

They were both deeply committed to their work at Abydos. The pair even provided basic medical help, with Calverley going on to work as a Civilian Relief worker during the Second Worl War, and nursed soldiers on the front lines in Crete during the Greek Civil War.

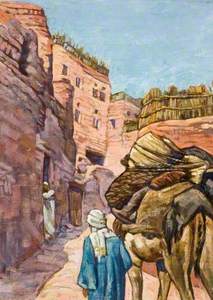

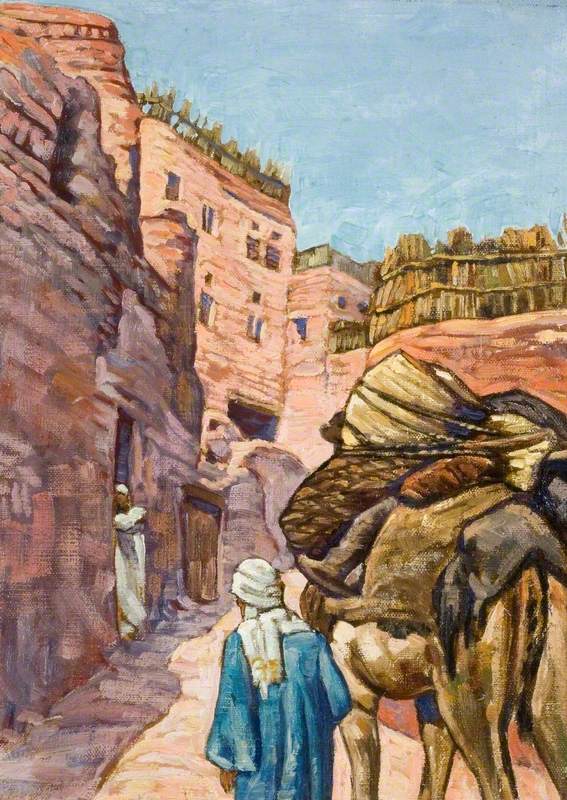

Arab Leading a Camel up a Steep Village Street

Myrtle Florence Broome (1888–1978)

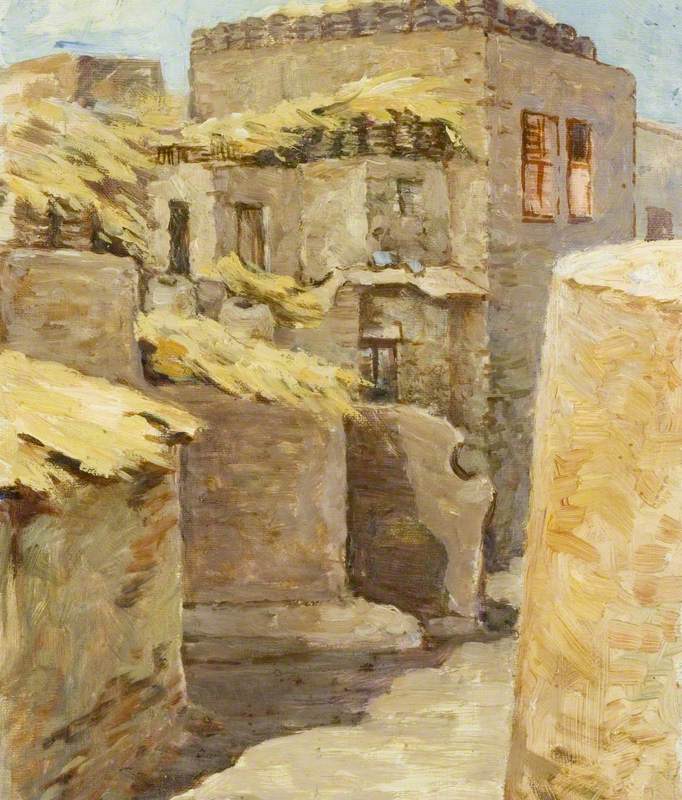

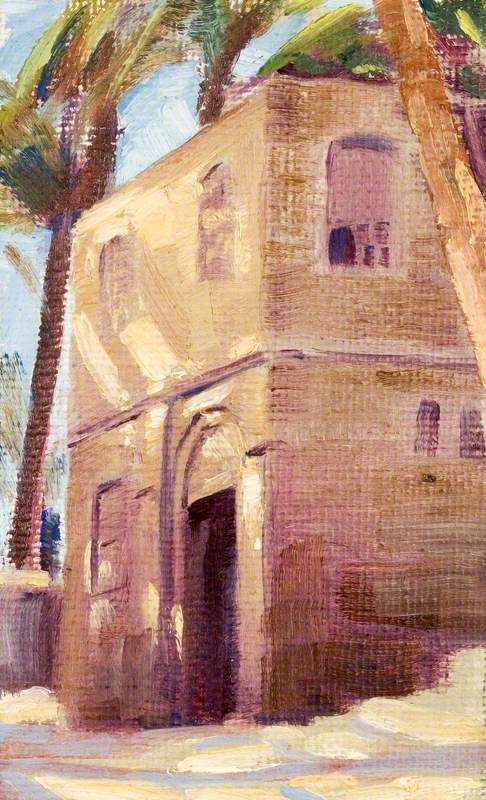

Outside of their artistic endeavours and supporting the local community, the two women travelled together throughout Egypt, often driving across the deserts in a Jowett car that was affectionately named Joey.

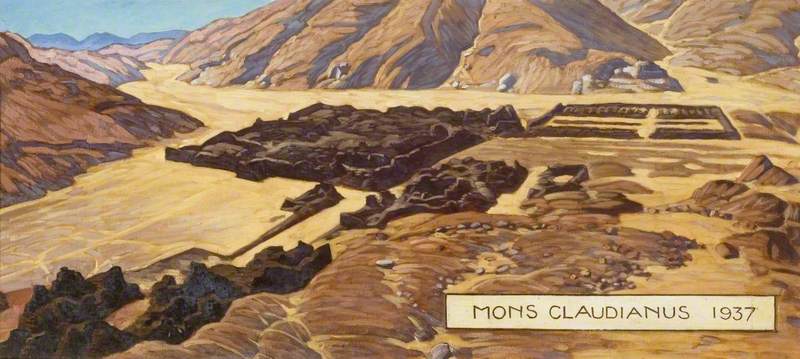

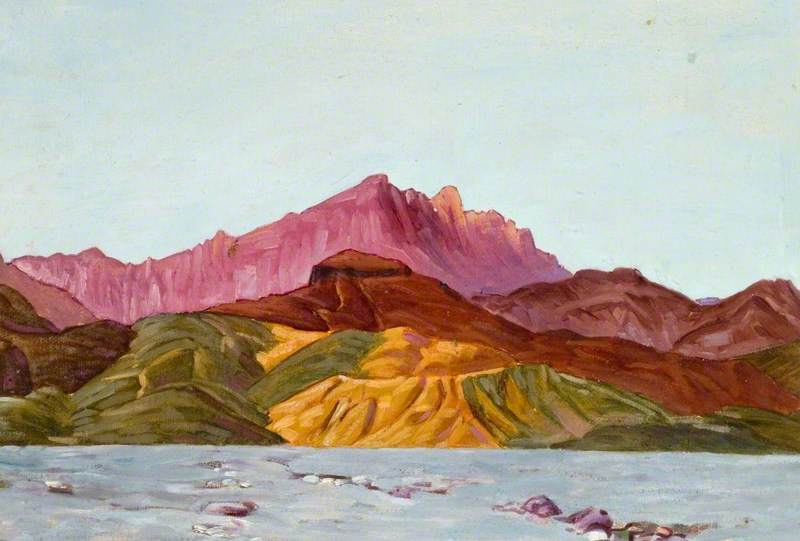

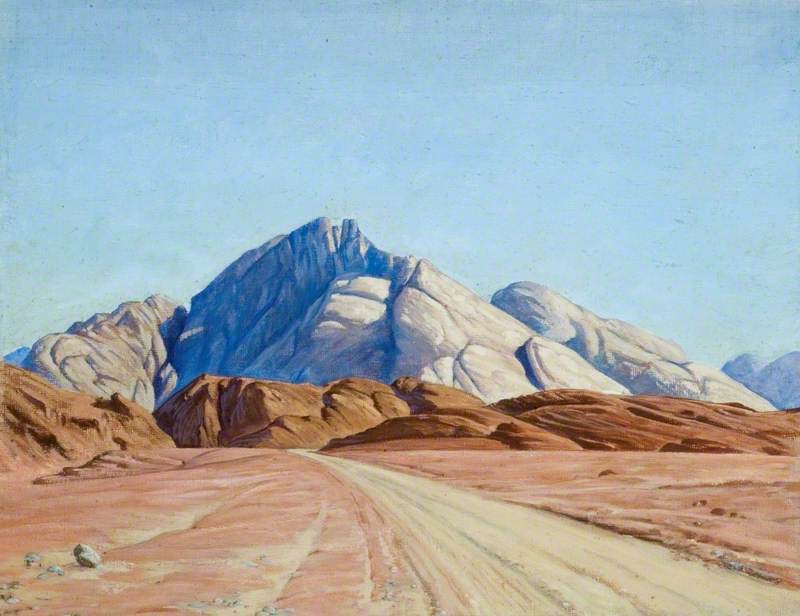

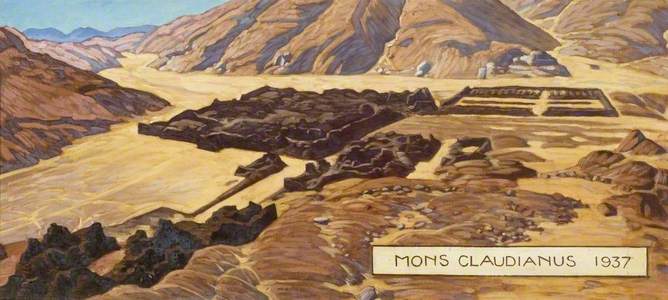

Broome found great joy in depicting desert landscapes too, a far cry from the surroundings of her home town, and explored many Roman quarries and mines with Calverley.

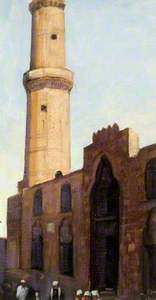

Egyptian Wadi with Ruined Structures

Myrtle Florence Broome (1888–1978)

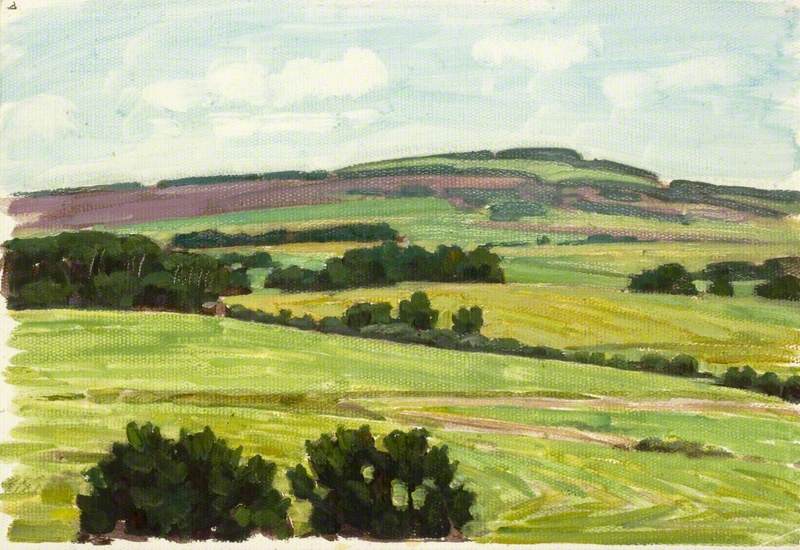

There is a beautiful contrast between Broome's landscapes of the English countryside versus the harsh desert conditions of Egypt. Everything is different – from the colour palette to subject matter – but the same delicate and considered technique remains, her command of light and shade particularly admirable.

Broome retired from Egyptology in 1937 and returned to England due to her father's illness. Questions remain about the nature of her relationship with Calverley and whether they were indeed romantically involved. Neither woman ever married, and the pair remained good friends until Calverley died in Toronto in 1959.

Notably, there is a great familiarity between Calverley and Broome's family. In one of Broome's letters, Calverley writes a short note in the corner to her companion's parents which she signs 'lots of love from your more or less adopted daughter.' In another, she thanks Broome's parents for letting Broome accompany her on this expedition, saying that she 'can't think of the camp without her.' Though there is no 'hard' evidence to support a romantic relationship between the two women, there is no denying the significant role that each woman had in the other's life.

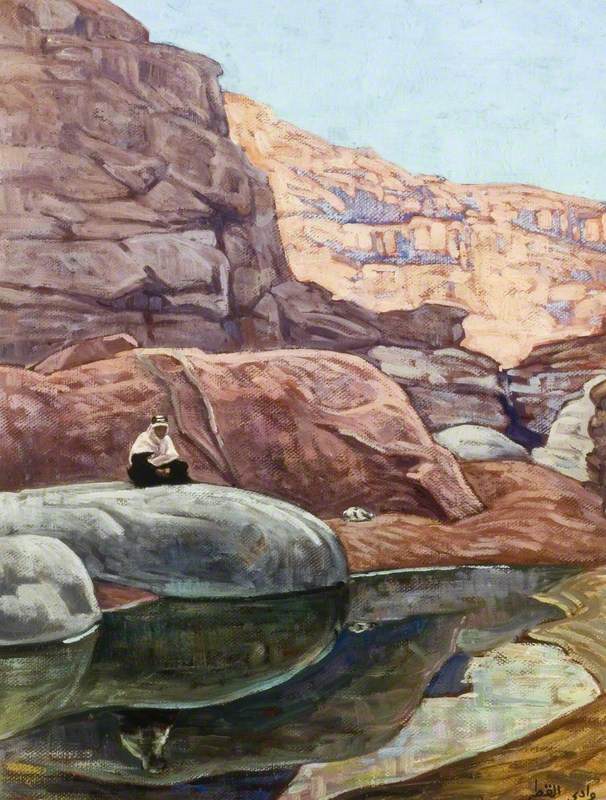

Arab Sitting on a Rock over a Pool in a Mountain Valley

Myrtle Florence Broome (1888–1978)

Broome and Calverley's painstaking work has proved invaluable for academics and their letter writing an intimate insight into Egyptian life. Both furiously passionate and talented, the lives of these extraordinary women and their contribution to the study of ancient Egypt should not be forgotten.

Flora Doble, freelance writer

Futher reading

There are many images of the Temple of Seti I at Abydos by Calverley and Broome on The Ancient Egypt Foundation website

The Griffith Institute at Oxford University holds letters by Broome and Calverley