Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby, was the mother of Henry VII, the first Tudor king. Born in 1443, she was the only child and heiress of John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, a grandson of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, fourth son of Edward III. Lancaster's adulterous affair with Katherine Swynford produced four children, all surnamed Beaufort after a French lordship he had once held.

The Beauforts were legitimated by Statute in 1397, after their parents married. In 1407, however, when the eldest, John Beaufort, Earl of Somerset, asked Henry IV to confirm their legitimacy, the king did so by his Letters Patent, but added the rider 'excepting the royal dignity'. Letters Patent could not overturn an Act of Parliament, yet there would be much debate about the Beauforts' right to the crown.

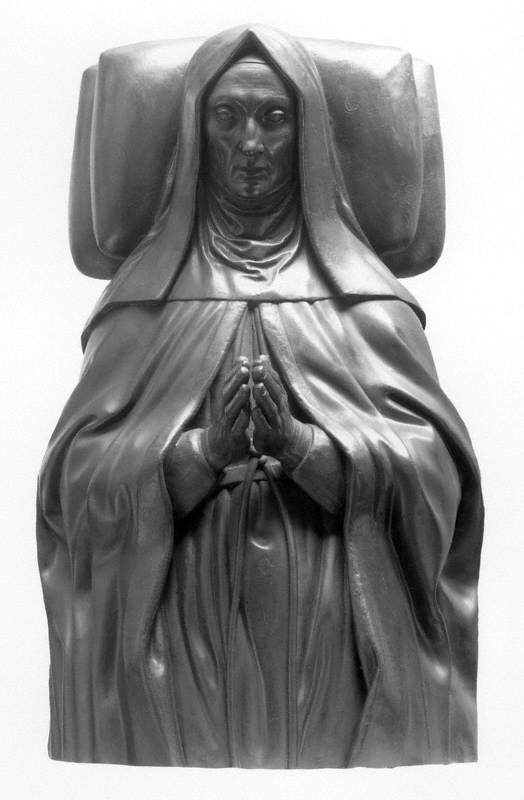

Lady Margaret Beaufort (1443–1509), Countess of Richmond and Derby, Foundress

late 16th C

unknown artist

Margaret was John of Gaunt's great-granddaughter. In 1455, at twelve, she married Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond, one of the sons of Henry V's widow, Katherine of Valois, by Owen Tudor. Edmund died of plague in 1456, leaving Margaret pregnant. In January 1457, aged thirteen, she bore her only child, Henry Tudor.

Henry VII (1457–1509)

(fictive cusped arch) c.1501–1509

British (English) School

Margaret adhered to the Lancastrian cause during the Wars of the Roses, but in 1472, after the House of York had overthrown the House of Lancaster, she prudently married Thomas Stanley, Earl of Derby, who was aligned to the Yorkists. After Richard III came to the throne in 1483, she schemed to place her son Henry, who had been in exile for twelve years, on the English throne. Modern claims that she was responsible for the murders of Richard's nephews, the Princes in the Tower, cannot be substantiated by contemporary evidence.

Lady Margaret Beaufort (1443–1509), Countess of Richmond and Derby, Foundress

16th C (?)

unknown artist

When Henry Tudor vanquished Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485 and established the Tudor dynasty, Margaret became a great lady, honoured as almost a second queen. She was a devout woman, who, even before her husband died in 1504, had become a vowess – a married woman who renounced sex – and took to wearing the austere nun-like robes with the white wimple and chin-barbe that feature in most of her portraits.

A great patron of learning, she founded Christ's College and St John's College at Cambridge. She died in 1509, shortly after the accession of her grandson, Henry VIII, and was buried in a fine tomb in Westminster Abbey surmounted by an effigy sculpted by Pietro Torrigiani.

Many portraits of Margaret Beaufort survive, although none from her lifetime. Most are of late sixteenth century date and were probably based on her effigy, although there may have been a lost original. The most famous is in the National Portrait Gallery, which dates from the late seventeenth century.

There are five examples of this type in Christ's College, Cambridge, and others in the Bodleian Library, Brasenose College, Jesus College, Lady Margaret Hall, Hever Castle, Minster House at Ripon, and the Royal Collection.

The one at Christ's College may be the earliest.

Lady Margaret Beaufort (1443–1509), Countess of Richmond and Derby, Foundress

16th C

unknown artist

In these portraits, Margaret appears as the image of piety, charity and philanthropy, the virtuous matriarch of a dynasty. The number of likenesses still in existence shows that there was a demand for them long after her death.

The earliest portrait of Margaret to survive is that by the Netherlandish artist Meynnart Wewyck, who worked for Henry VII. Research undertaken in 2019 uncovered documentary evidence that it was painted before 1521. It shows her kneeling at a prayer desk in a richly furnished closet and hangs in the Master's Lodge of St John's College, Cambridge, which also owns three other versions, including one by Rowland Lockey, dating from the 1590s.

The Wewyick portrait was probably the one paid for by Margaret's executors in 1511–1512: 'To Maynerde the painter, for painting the picture of my lady the King's grandmother in Christ's College.'

Most people think of Margaret Beaufort as an old lady in nun-like garb. But two earlier images give a very different impression.

Book of Hours of Margaret Beaufort, showing the Countess praying to St. Margaret pic.twitter.com/o516JefKw7

— Hilary Chaplin (@hillaryssteps) September 23, 2014

Her illuminated Book of Hours at Alnwick Castle, which was commissioned before 1499, when she took her vow of chastity, shows her at prayer, wearing a gown with an armorial skirt and a sideless surcoat trimmed with ermine. On her head is the coronet of a countess; what can be seen of her hair suggests that it was fair. This is probably not a portrait, but a representation of a royal lady who was conscious of her high lineage and signed herself 'Margaret R' – the R being for Richmond, although many might have read it as 'Regina'.

There is a beautiful stained-glass window depicting Margaret Beaufort in All Saints' Church at Landbeach, Cambridgeshire.

OTD 1443 Margaret Beaufort was born at Bletsoe Castle. This beautiful glass is thought to be the only likeness of a younger Margaret, now in the church at Landbeach. To mark M’s birthday head over to my Instagram @historian_nicola for my latest book giveaway! @OMaraBooks pic.twitter.com/8QCGX06337

— Dr Nicola Tallis (@NicolaTallis) May 31, 2020

It was moved there from Wimborne Minster in Dorset, where her parents were buried. Margaret wears an elaborate gable hood, suggesting that the glass was made in the early years of Henry VII's reign, probably when she was in her 40s. Some attempt at portraiture may have been made, since the features, especially the nose, compare with those in the later portraits.

A portrait of a woman purchased by the National Portrait Gallery in 1908 was long thought to be a younger Margaret Beaufort.

Unknown woman, formerly known as Lady Margaret Beaufort

unknown artist

Doubts as to the identification were expressed early on, and an x-ray taken in 1939 revealed a different image of a woman beneath, probably from an early sixteenth-century Flemish altarpiece. It is now known to have been overpainted in the nineteenth or early twentieth century by an artist who wanted to sell it as a portrait of Margaret Beaufort, whose maiden arms he painted on it.

Unknown woman, formerly known as Lady Margaret Beaufort

(copy after an unknown painter)

Wilfred Bernard Egan (1877–1913)

There are copies at Christ's College, Cambridge, and at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.

Margaret Beaufort does not deserve the sinister reputation she has acquired in the last few decades.

John Fisher, who knew her well and preached her funeral sermon, said of her: 'She was bounteous and liberal to every person. Of marvellous gentleness she was unto all folks, but specially unto her own, whom she loved right tenderly. Unkind she would not be unto no creature. She was not vengeful or cruel, but ready to forget and to forgive injuries done unto her.'

When she died, he related, all were in tears and 'all England for her death had cause of weeping'.

Alison Weir, author and historian