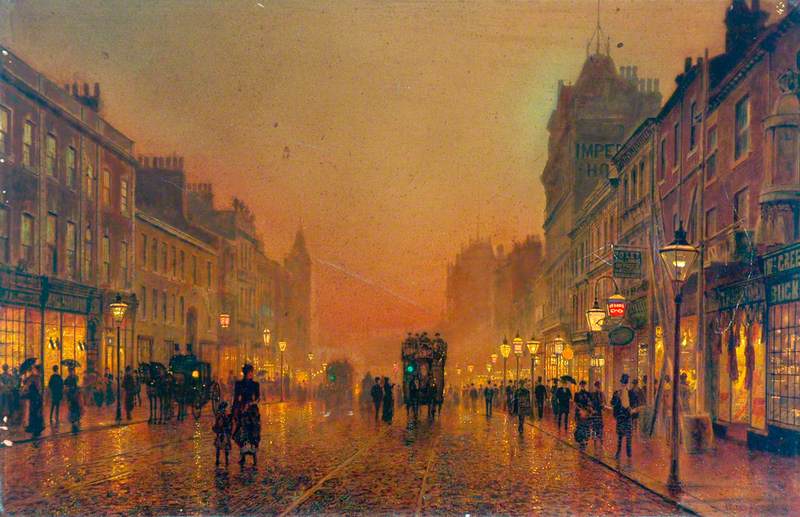

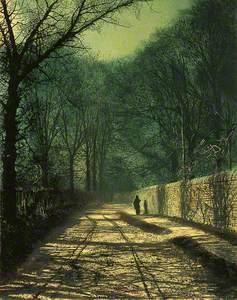

John Atkinson Grimshaw (1836–1893) wanted very much to be an artist. In this he succeeded, producing works of lasting appeal. Evocations of moonlit high-walled lanes, moonlit seaside views and gaslit city streets come to mind, made and remade with consistent skill.

Born in Leeds to parents of modest means, he first worked as a clerk for the railways before deciding he wanted to paint, and he was apparently self-taught. By his mid-30s, his paintings were so commercially successful that he was able to live (albeit beyond his means) in a manor house, Knostrop Old Hall, in Leeds, while renting a second house at Scarborough on the coast.

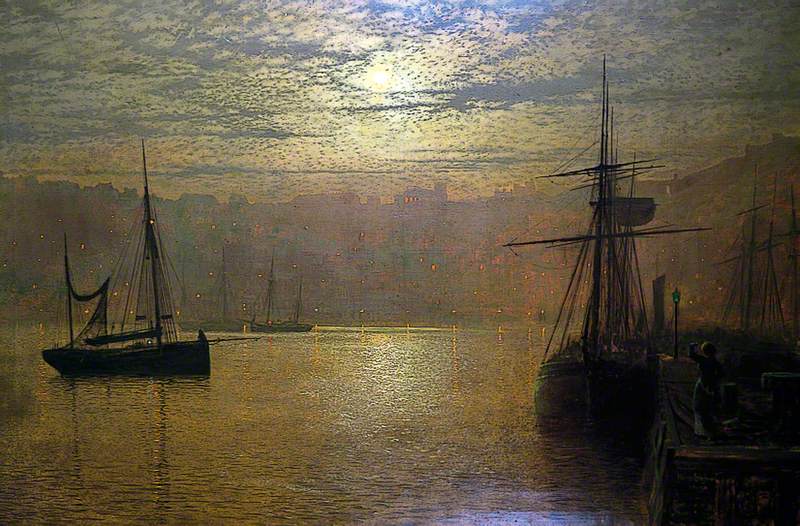

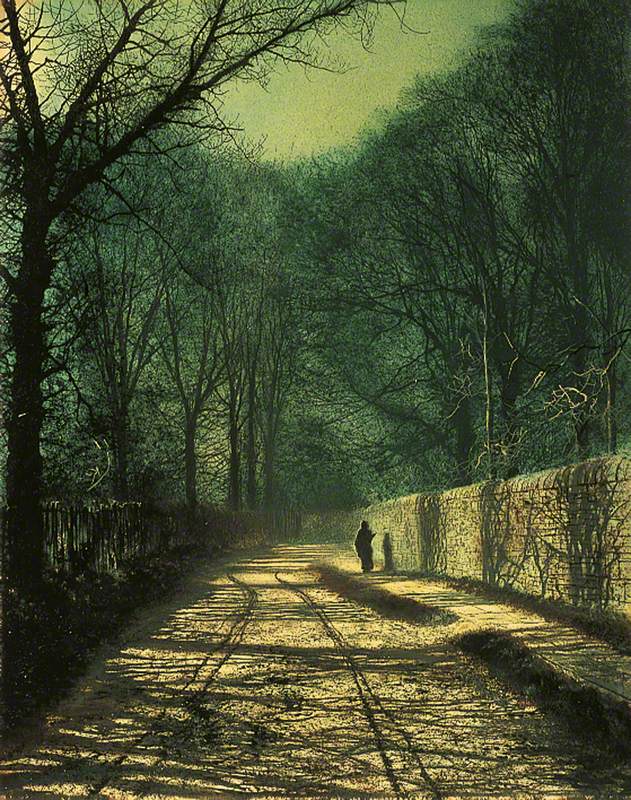

Night scenes were his speciality. From his first in 1867, Whitby Harbour by Moonlight, to those of his final year, Grimshaw painted dozens of them. And in these night skies rarely was the Moon less than full, and never was the effect less than Romantic. So avid was his devotion to the nocturne that when asked to provide paintings in support of a bid to create a public park in Leeds, he chose to paint it by night, haunted by solitary silhouetted figures.

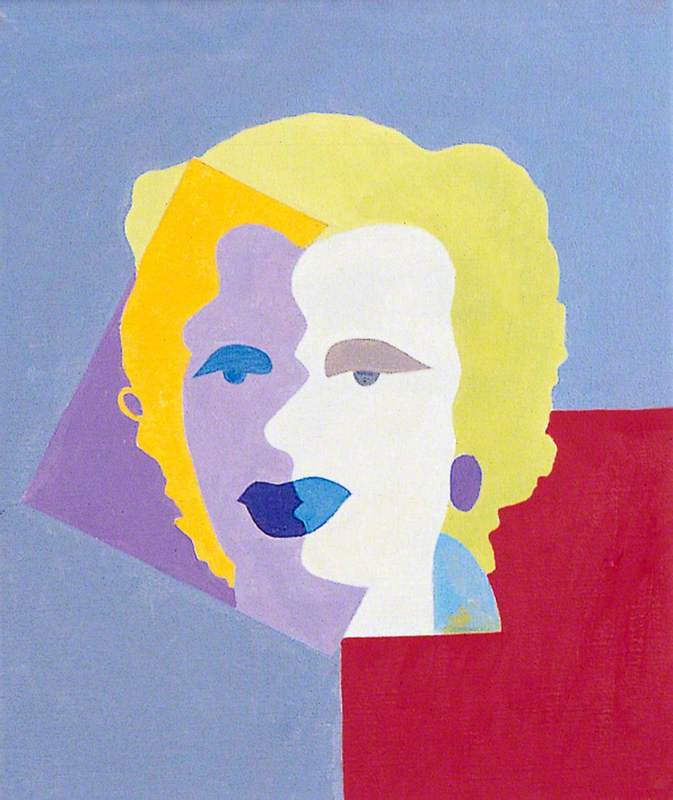

Tree Shadows on the Park Wall, Roundhay, Leeds

1872

John Atkinson Grimshaw (1836–1893)

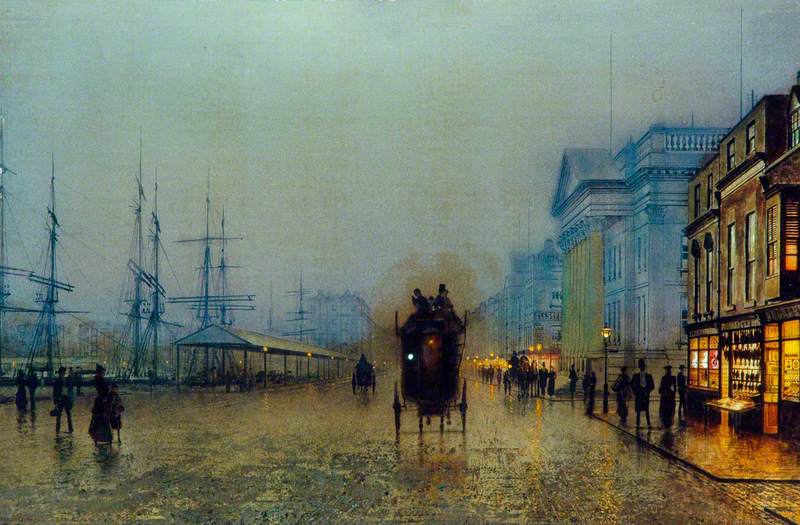

Grimshaw provides obediently reflective surfaces upon which the moonlight can shine, whether it be the ripples of the sea or the rain-wet surface of cobbled streets. His city views are almost always wet ones, with ladies (often the same lady, his model Agnes Leefe) poised to open an umbrella.

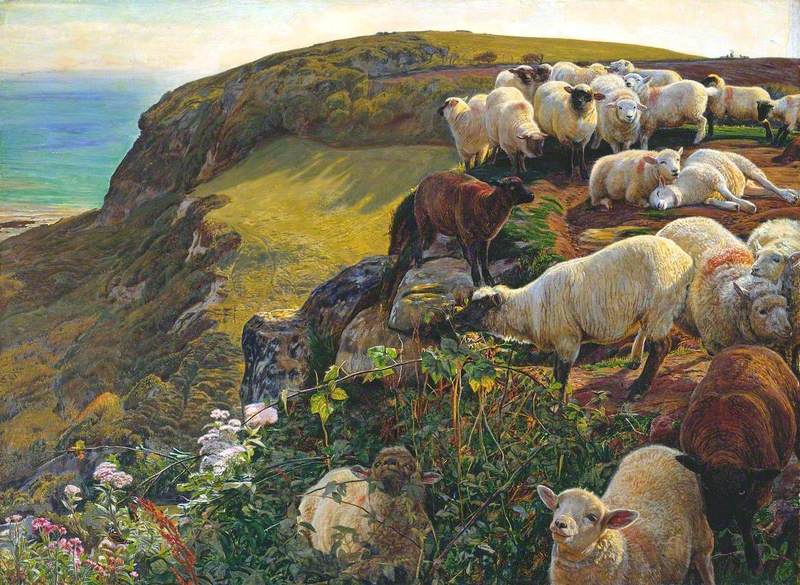

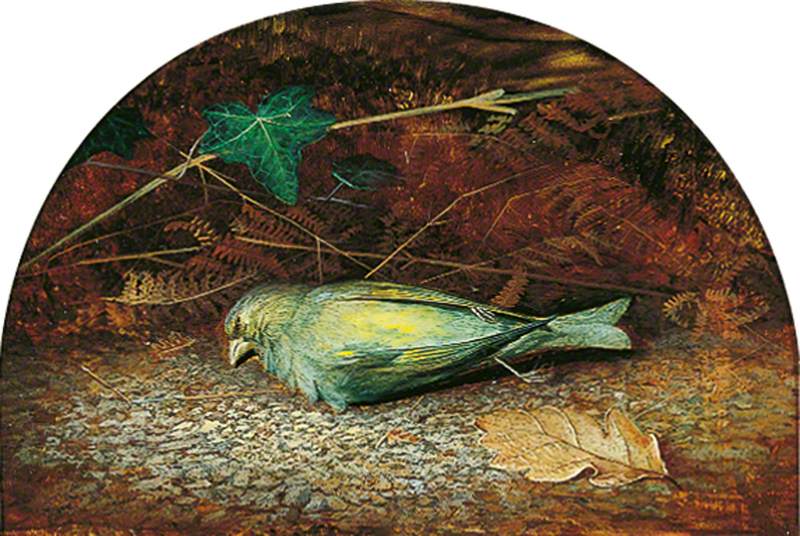

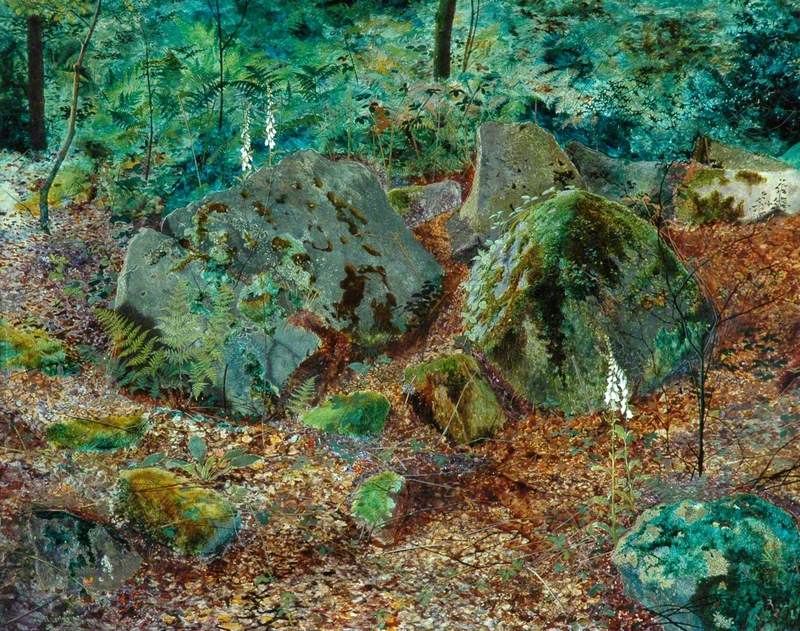

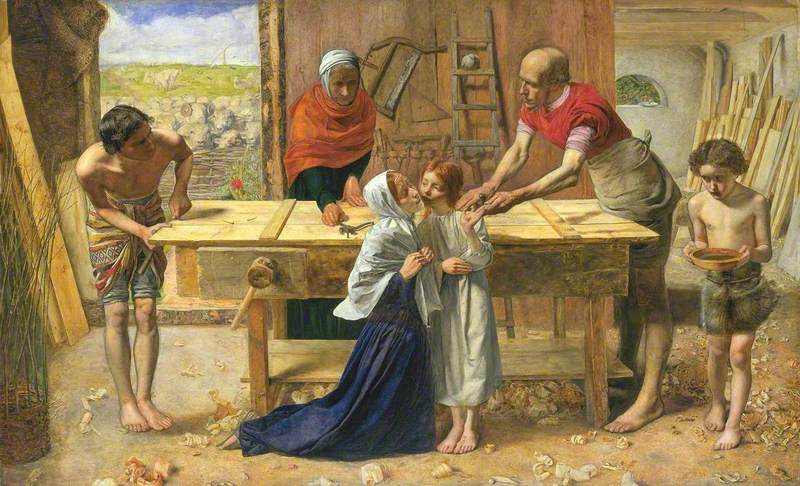

In his early career, Grimshaw was drawn to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, an influence which is evident in both his themes and his palette. He adopted the highly detailed approach found in works such as William Holman Hunt's Our English Coasts (1852), as well as a vivid polychromatic style, tending at times towards the lurid. The striking use of colour in these paintings serves the sharply observational approach in which everything is pinpointed and particularised.

At this time, painters were influenced by close-up photographic studies of natural features, and Grimshaw added to the genre with A Dead Linnet and A Mossy Glen. These are among Grimshaw's earliest works. He honed his skills on still lifes which were arrangements of objects found on countryside walks: leaves and lichen-encrusted twigs and the body of a dead bird. Admirable as technical studies, they display the illustrative exactness of the glass cabinet in a natural history museum.

Like the Pre-Raphaelites – and the French artist James Tissot, who also influenced him – Grimshaw was industrious in his output of beautiful, pensive ladies in decorous surroundings, their flawless complexions shining Moon-like in settings of insistent detail.

The Rector's Garden, Queen of the Lilies

1877

John Atkinson Grimshaw (1836–1893)

These pictures show off his technical proficiency and were quickly put on the market, where they sold well. Their appeal to popular taste is obvious, their sentiments signalled by titles such as Meditation, Il Penseroso (The Thinker) and Autumn Regrets.

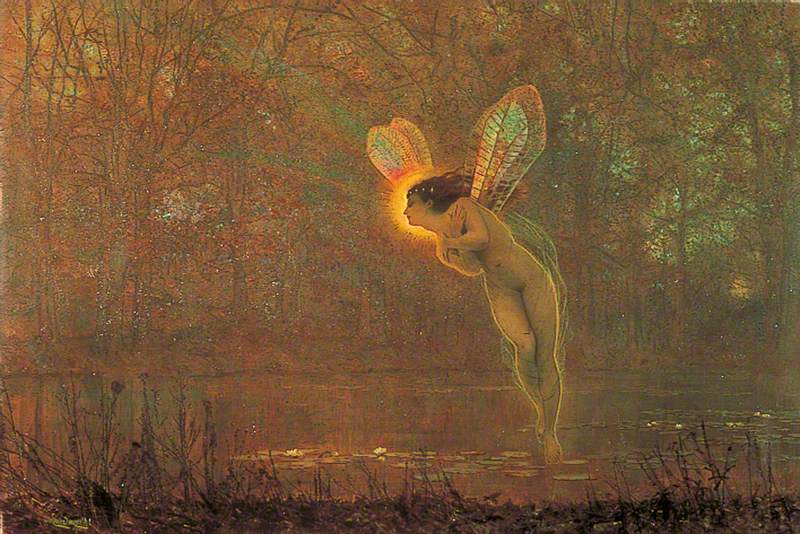

Autumn was Grimshaw's season. The cynic will find formulaic the repetition of leafless trees, silhouetted against a variety of lighting effects. Even among his 'fairy' pictures, another popular strand of his output, prominent are Dame Autumn and Iris. Grimshaw attributed an autumnal significance to the mythical figure of Iris, writing these lines on the back of the painting: 'Now Iris being chief messenger unto / Juno was sent on her Autumn errand to wither ye flowers and leaves / On coming atte ye Water Lily, being / enamoured ye beauty thereof, She / did hesitate / and was changed into a rainbow for her disobedience'.

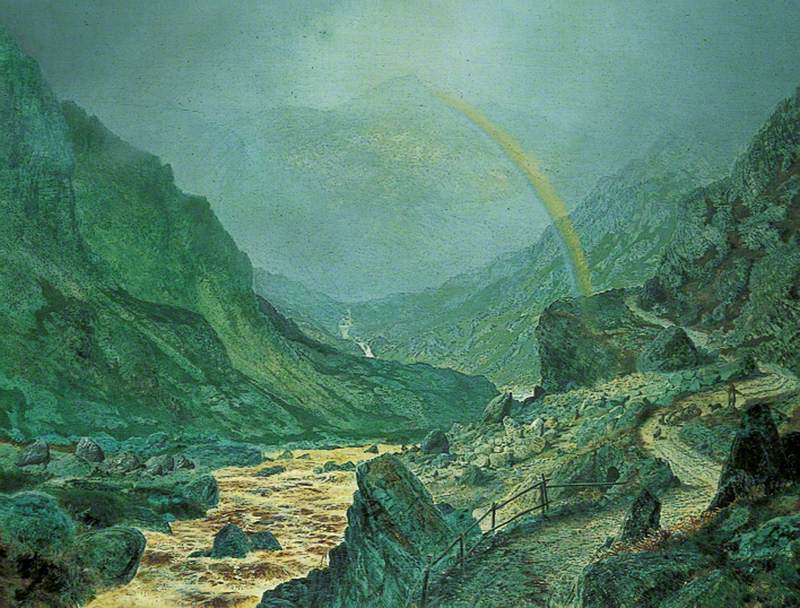

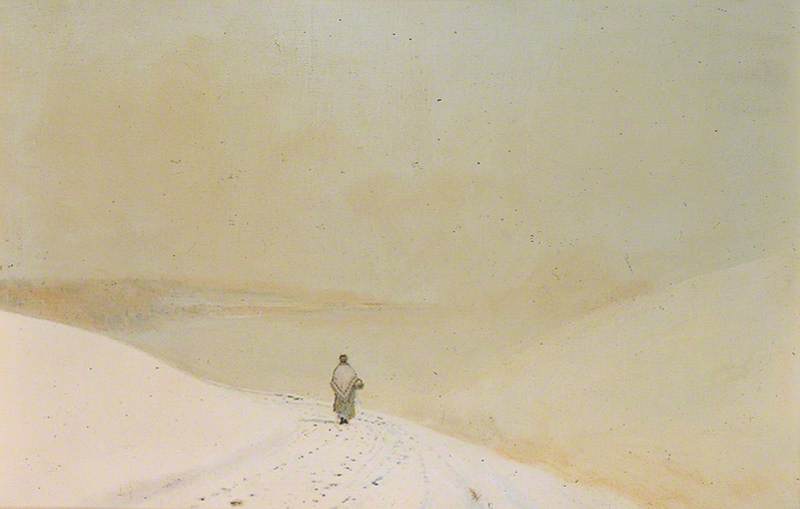

The scarcity of surviving letters and other personal documentation means that some influences remain speculative, but Grimshaw's art brings to mind the works of Caspar David Friedrich, another painter of moonlight and mood. Like Friedrich, Grimshaw was not an accomplished figure painter, and his figures are often sketchy and obscure, their backs turned to us as they look out onto expansive panoramas. The resemblance to Friedrich occurred to one official of The National Gallery in 1973, who suggested that instead of buying Friedrich's Easter Morning, they 'might as well buy an Atkinson Grimshaw and pocket the difference'!

Easter Morning

c.1828–1835, oil on canvas by Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840)

Grimshaw's Snow and Mist (Caprice in Yellow Minor) evokes both Friedrich and James McNeill Whistler, its subtitle borrowing from Whistler's habit of relating his paintings to musical forms, namely 'Nocturnes', 'Harmonies' and 'Symphonies'.

Snow and Mist (Caprice in Yellow Minor)

1892/1893

John Atkinson Grimshaw (1836–1893)

The personal association between Grimshaw and Whistler is unclear. They were active at the same time, working from studios in Chelsea, but the claim that Whistler credited Grimshaw with the innovation of the nightscape ('I thought I had invented the Nocturne, until I saw Grimmy's moonlights') belongs to Grimshaw family lore and has not been corroborated. Indeed, biographies and other studies of Whistler find no place for Grimshaw – for example, Daniel E. Sutherland's 2014 biography.

Nocturne: Blue and Gold - Old Battersea Bridge

c.1872–5

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

Whistler's night scenes differ from Grimshaw's in that they are primarily experiments in colour veering towards abstraction. With few exceptions, Grimshaw's are literal and illustrative. Snow and Mist: Caprice in Yellow Minor is one of the few works which approaches Whistler's use of dominant colour, and the Whistlerian title suggests this influence. Nightfall down the Thames (1880) is bathed in a sulphurous moonlight, but the ships are, as usual, precisely drawn and lead the eye pleasingly to the neat dome of St Paul's.

In the 1840s the innovation of photography had arrived. The influential art historian John Ruskin, no less, approved the use of daguerreotypes – early photographic images – as aids to drawing. While artists' use of photographs as aide-mémoires – a kind of instant sketchbook – was quite common (by Delacroix, Eakins and Holman Hunt, for example), Grimshaw used them to copy from directly (and in a few instances, to paint over). Bowder Stone is one of a number of works that were based on photographs. As such, it looks like a photograph that has been tinted or subjected to a polychromatic filter.

Landscapes such as Bowder Stone possess a 'frozen' and 'airless' quality, as Alexander Robertson describes it, which surely results from Grimshaw's method of mechanical copying. Ruskin opposed slavish copying from photographs, the unfortunate consequences of which we see in some of Grimshaw's works.

Ingleborough from under White Scar, Yorkshire Limestone Strata

1868

John Atkinson Grimshaw (1836–1893)

A more arresting landscape is Ingleborough from under White Scar, which captures the atmosphere of its forbidding location in cold, dramatic zones of colour. This painting is unlikely to have been based on a photograph because no single view would provide this composition. Here, perhaps, we see the virtue of working in situ and eschewing photographic blueprints. The artist, liberated from the constraint of the photograph, created 'one of the most heroically conceived pictures he ever made' (says Frank Milner in Sellars' Atkinson Grimshaw).

However, Grimshaw's compositions too often have a Sunday painter's regard for a tidy, balanced arrangement which photography did not disturb. While the Impressionists, among others, found in photography the oblique view, the cropped image and a sense of the spontaneous moment, Grimshaw largely employed the new technology as a convenient way of capturing a scene.

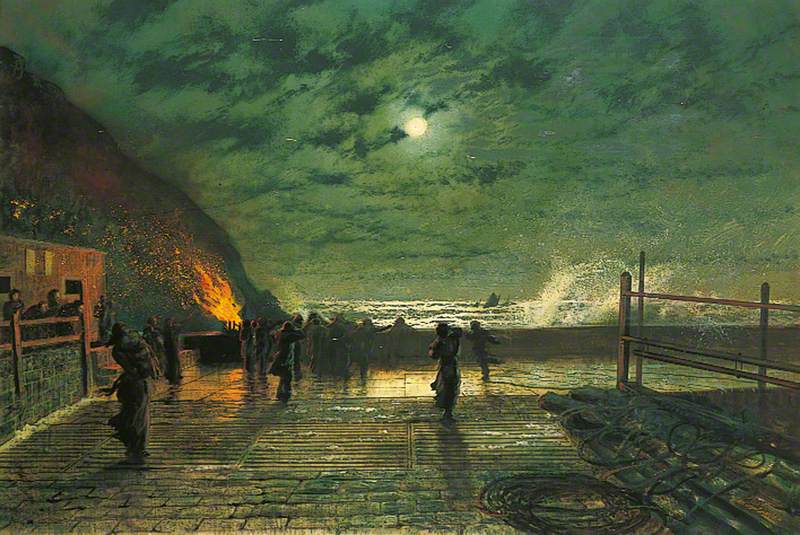

Grimshaw was able to evoke energy and movement when he wanted to. An untypically turbulent scene, In Peril (The Harbour Flare), allowed him to paint sea spray and gale-blown flame, all under a scudding moonlit sky. The fire from a burning barrel acting as a flare is split into spark-like embers by the wind, bringing to mind Whistler's infamous Nocturne in Black and Gold, the Falling Rocket, painted just a few years earlier. Such drama, however, is rare in Grimshaw's works.

Sic transit gloria mundi depicts a destructive fire at the Spa Saloon, Scarborough. The figures in the foreground look on helplessly, while the fire, a jewel of flame in the distance, competes with – but is outdone by – the ravishing moonlight and its reflection on the waters.

Sic transit gloria mundi (The Burning of the Spa Saloon)

1876

John Atkinson Grimshaw (1836–1893)

Light was unquestionably Grimshaw's obsession. He scrutinised the prismatic effects in objects such as the glass of candelabra, and his daughter recalled bringing him pieces of old glass found in the garden which he added to his collection of refracting paraphernalia.

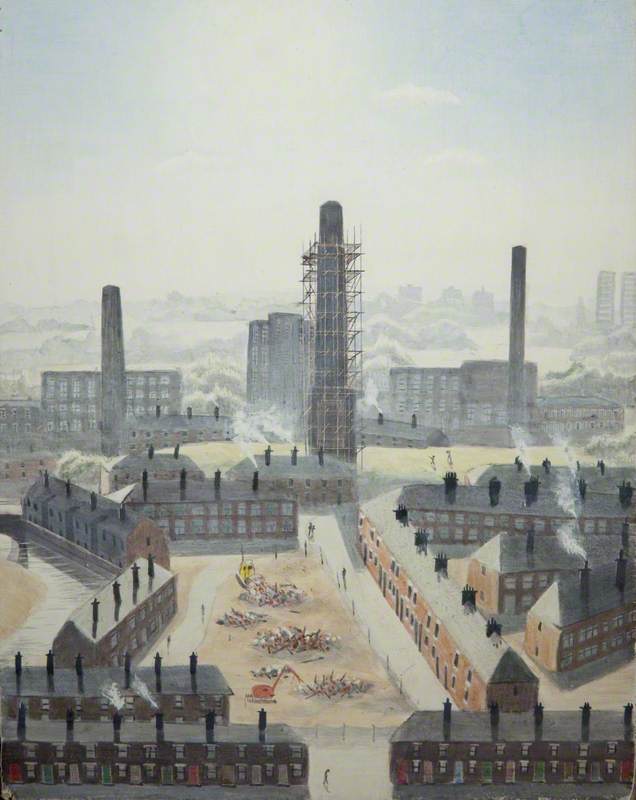

As a Victorian, Grimshaw witnessed the proliferation of gas lighting in his hometown of Leeds, and captured the orange glow of lamps and shop windows that any pedestrian in a big city after dark will recognise. We can only imagine the transformative effect of artificial light in a city which was dark with smoky industry, a place of the kind that Dickens called Coketown in Hard Times: '… a town of machinery and tall chimneys, out of which interminable serpents of smoke trailed themselves for ever and ever, and never got uncoiled'.

But Grimshaw was no social realist. The rapidly growing town of Leeds contained much ugliness and deprivation, but much as snow prettifies a scene by disguising its reality, Grimshaw bathed his paintings of northern towns in moonlight. According to Alexander Robertson in Sellars' Atkinson Grimshaw, he was interested in 'capturing their modernity […] and at the same time making them seem timeless in the way he covered them with a veneer of age, seeing them by moonlight'. Ever the Romantic, there is little by way of social commentary in Grimshaw.

Grimshaw died of cancer at the age of 57. Despite his sales and years of hard work, the state of his finances was such that Knostrop Old Hall had to be sold to raise money for his family, along with its contents and those of his studio. A recent critic (see Poë's 'The Magician of Aestheticism') imagined a different career for Grimshaw:

'If only he had received a proper training (he was never adept at painting the figure); if only short-term necessity had not impelled him to adopt the professional practices of a hack, then what sort of a painter might Grimshaw, with his natural gifts and originality, have been?

However we may speculate, we are left with the works of a popular painter who is the pride of his hometown of Leeds. A 2011 retrospective in Harrogate attracted huge numbers of visitors, many of whom would bridle at the sneering judgement, typical of many critics, that 'like the potency of cheap music, Grimshaw's paintings have a flavour and appeal of their own.'

His pictures leave the story of art largely unperturbed, and for some are undeserving of attention. Atmospheric and theatrical, glamourised by a range of radiant effects, they provide an easy pleasure which will doubtless endure.

Adam Wattam, writer

Further reading

Elaine Grimshaw, 'A Daughter Remembers', Yorkshire Post, 1963, in Joseph Ruzicka, The City at Night in Nineteenth-Century British Art, PhD dissertation, 2000

Simon Poë, 'The Magician of Aestheticism', Apollo, 2011

Alexander Robertson, Atkinson Grimshaw, Phaidon, 1988

Jane Sellars (ed.), Atkinson Grimshaw: Painter of Moonlight, The Mercer Art Gallery, 2011

Julian Treuherz, Victorian Painting, Thames and Hudson, 1993

William Vaughan, Friedrich, Phaidon, 2004