In the competitive world of High Renaissance Rome, rivalries ran hot. Michelangelo's ferocious temperament was fuelled by antagonism with Leonardo and Raphael. This notorious terribilità has become part of the mythology of Michelangelo, the archetypal lone genius. So it may come as a surprise that when Venice's greatest oil painter moved to Rome in the summer of 1511, Sebastiano Luciani (1485–1547) found in Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) not only a friend, but a collaborator.

Room three, showing 'The Raising of Lazarus' and 'Pope Clement VII'

This is the first exhibition to chart their 25-year friendship and its fruits. Yet this partnership has been hiding in plain sight in London museums for centuries. The first work to enter the nascent National Gallery's inventory in 1824, The Raising of Lazarus, was painted by Sebastiano, but two drawings by Michelangelo in the British Museum's collection reveal the Florentine's role in designing the figure of Lazarus. At the moment of his resurrection by Christ, Lazarus' unmistakeably Michelangelesque body fights through rigor mortis into animation. Around him onlookers react variously to the miracle, their expressive faces hinting at Sebastiano's prowess as a portraitist.

The Raising of Lazarus

about 1517-19

Sebastiano del Piombo (c.1485–1547)

The exhibition celebrates 500 years since Sebastiano started this painting, which hangs at its centre in a resplendent new frame, alongside Michelangelo's drawings and later portraits of the patron, Giulio de' Medici, after he had become Pope Clement VII. Its commission points to the political intrigue and artistic competition, which lay behind this amity. The patron was cousin to Pope Leo X, and a childhood friend of Michelangelo, who had learned to sculpt in the household of Lorenzo de' Medici, 'the Magnificent'.

Giulio became archbishop of Narbonne in 1515, bolstering a fragile allegiance between the Papacy and France. He commissioned two works for the Cathedral, pitting Sebastiano against Raphael, whose Transfiguration never left the Vatican. The Venetian's distrust of Raphael is evident in his letters to Michelangelo, then living in Florence. After all, Raphael had inadvertently brought Michelangelo and Sebastiano together when the Venetian first moved to Rome.

In his suburban villa today known as the Villa Farnesina, the Sienese banker Agostino Chigi commissioned Sebastiano and Raphael to paint individual parts of the story of Polyphemus and Galatea on the same wall. Raphael, whose dazzling Galatea was painted second, ignored the scale and horizon line established in Sebastiano's Polyphemus. Nonetheless, Sebastiano drew praise for his confident and innovative use of colour in his first Roman commission.

Here is the full wall at the Villa Farnesina which showcases the Raphael fresco. pic.twitter.com/SxThywK0xK

— ALWAYS LEARNING (@planetearthx2) September 8, 2020

This incident would not have escaped Michelangelo, still smarting from the recent comparison of his in-progress Sistine Chapel ceiling to Raphael's Stanza della Segnatura. Critics praised these two Vatican projects for Pope Julius II, but declared Raphael the better painter because he combined Michelangelo's skilful and inventive positioning of figures with a more sophisticated use of colour. Michelangelo saw an opportunity to make Sebastiano, a skilled colourist and oil painter, an ally. By providing Sebastiano with drawings and designs, Michelangelo hoped that they could marginalise Raphael.

Room one, showing 'Manchester Madonna' and 'Judgement of Solomon'

Their collaboration relied on their different artistic training so the exhibition opens with early works from Florence and Venice. As a Venetian, Sebastiano learned to exploit the capacity of oil paint to create luminous colour that plays a dominant expressive and compositional role. Like his mentor Giorgione, he imbued his works with atmospheric and lyrical qualities, evident in his unfinished Judgement of Solomon.

The Judgement of Solomon

(unfinished) 1505–1510

Sebastiano del Piombo (c.1485–1547)

Sebastiano also applied his paint in an improvisatory way quite anathema to the technique practiced by Michelangelo, seen in his early unfinished Manchester Madonna.

The Virgin and Child with Saint John and Angels ('The Manchester Madonna')

about 1497

Michelangelo (1475–1564)

In the studio of Domenico Ghirlandaio, Michelangelo learned to conceive his composition and draw it out on paper before transferring it to the wall or panel, as demanded by quick-drying fresco and egg tempera. The Florentine emphasis on drawing is also present in sculptures; the chisel marks in his Taddei Tondo resemble the hatched modelling of his drawings, while his drawn lines evoke sculptural forms.

The Virgin and Child with the Infant Saint John

(known as the Taddei Tondo) c.1504–1505

Michelangelo (1475–1564)

Michelangelo and Sebastiano's complementary skills are evident in their first collaboration, a Lamentation over the Dead Christ for the church of San Francesco in Viterbo. Michelangelo had already sculpted this subject for the famous Vatican Pietà. He revised his earlier design to place Christ on the ground, almost as if on the church's altar. Sebastiano situated the figures in a nocturnal landscape, unprecedented at that scale, and painted with astonishing freedom, which inspired great admiration.

Michelangelo's life drawing of a young man with clasped hands to perfect the Virgin's pose gives a partial explanation of the masculine features of Sebastiano's Madonna. Freeform sketches by both artists on the reverse of the panel testify to their close collaboration. Things changed in 1516 when Michelangelo was sent to Florence by Pope Leo X to work on the façade of the church of San Lorenzo. He would not resume residence in Rome until 1534.

Room two with the Viterbo 'Pietà'

The distance did not hinder their friendship or prevent their collaboration, as evident in the Raising of Lazarus. It generated a revealing correspondence. Michelangelo, the cultivated Florentine poet writes eloquently in appropriately exquisite handwriting. Sebastiano, the middle-class Venetian, writes in his local dialect, with evident reverence for his friend's artistic prowess. In 1519 Michelangelo became godfather to Sebastiano's first son, and from this point on they address each other as kinsmen. Sebastiano became one of Michelangelo's trusted middlemen in Rome, overseeing the installation of a classically inflected, nude statue of Christ in the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in 1521.

Room four, with two Risen Christs.jpg)

This was his second, radically revised version of a statue he had undertaken for a Roman patrician family. He had abandoned work on the first version in 1516 due to a flaw in the marble; it would be finished by another sculptor in the early seventeenth century. The first version had sunk into obscurity and was only rediscovered 20 years ago, and this exhibition offers the first opportunity to compare them.

The dynamic twist of the body from Michelangelo's design for Lazarus is reimagined in another resurrection. The Risen Christ is a subject that obsessed Michelangelo artistically and spiritually, and an exceptional collection of drawings shows him exploring it beyond his sculpture and perhaps beyond any commissioned project.

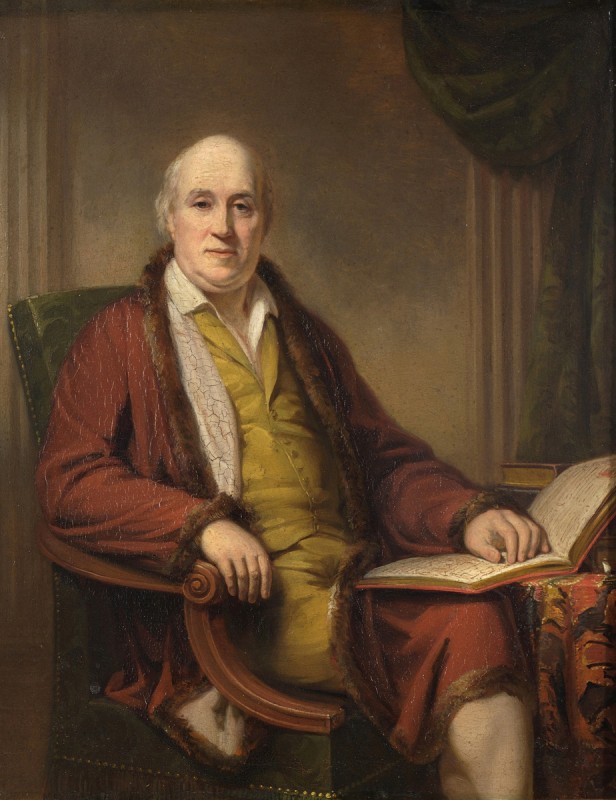

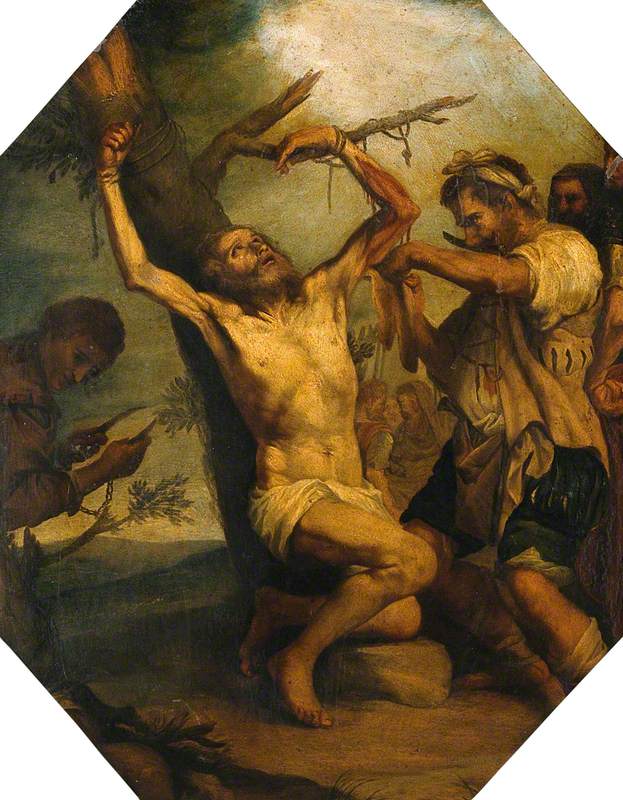

The collaboration's most influential product was a chapel at San Pietro in Montorio in Rome. The patron was their mutual friend and Michelangelo's broker Pierfrancesco Borgherini; a portrait by Sebastiano which likely shows this banker gives some insight as to why Michelangelo's correspondence concerning this young man reveals clearly that he was infatuated with him. Upon commission in 1516, Borgherini had expected the Florentine to provide the designs, but Michelangelo only managed to provide drawings for the central Flagellation of Christ, while Sebastiano finally completed the rest on his own between 1518 and 1524.

Room five, showing Borgherini chapel and drawings

Sebastiano painted the upper sections in fresco, but switched to oil for the lower parts, including the Flagellation. Although an old technique, the method of applying oil to the wall was little understood in Rome and Sebastiano's successful implementation of the technique was widely acclaimed. The atmospheric effect he achieved was unprecedented and helped animate a design that became immensely influential.

Yet Sebastiano's great innovation in the application of oil paint would cause a rift in a partnership that ironically had initially been premised exactly on his skill in that medium. In 1534, much to Sebastiano's delight, Michelangelo returned to Rome to paint the Last Judgement on the Sistine Chapel's altar wall. On what appears to have been Sebastiano's advice, the wall was prepared for painting in oil. However, in early 1536 Michelangelo ordered it plastered anew for fresco, the technique in which he completed it. He would later deny it, but Michelangelo must initially have approved of the idea and perhaps even tried his hand at painting the wall in oil before deciding it did not suit him.

Michelangelo disowned Sebastiano, describing him to his confidantes and biographers as lazy, in part because he painted in oils, a 'feminine' medium to fresco's masculine qualities in Michelangelo's aesthetic. Sebastiano was indeed less productive in his later years. Indeed, recent political events had changed him. Evidence indicates that during the Sack of Rome by Imperial troops in 1527 Sebastiano remained by the Pope's side during the seven-month siege he endured in the Roman Castel Sant'Angelo.

In 1531 the Pope rewarded the artist's loyalty by appointing him piombatore, carrier of the papal seal, earning him a nickname as well as a stipend. The sack affected him greatly. He wrote to Michelangelo 'I still don't feel I am the same Bastiano.' The austere, abstracted approach to form and intense spirituality he achieved, evident in his late Visitation mural, was highly original. But he had clearly moved away from Michelangelo's influence, seen in his earlier Visitation, on loan from the Louvre, painted during the height of their friendship, with its bright, deeply saturated colours.

Room six, showing two 'Visitations'

Sebastiano's work helped consolidate and define the Roman style established by Michelangelo, Raphael and others, becoming the model for much of Roman art of the next century and a half and reverberated significantly beyond Italy, notably in Spain and France. Moreover in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries he became highly popular in Britain.

A search of Art UK shows that works by, and copies of, Sebastiano are more prevalent in British public collections than may be expected for an artist whose name has been so eclipsed by the great masters of his milieu. This exhibition encourages a second look at an artist judged 'altogether unique' by Michelangelo, that most discriminating of critics.

Rosalind McKever, Harry M. Weinrebe Curatorial Assistant

'The Credit Suisse Exhibition: Michelangelo & Sebastiano' was at The National Gallery, London, until 25th June 2017