In the 1830s Turner and Constable clashed over the former's introduction of red on varnishing day at the Royal Academy, a visually striking element that drew viewers to Turner's work – to the detriment of attention paid to neighbouring artworks.

Look at the carefully calculated paintings by Meredith Frampton (1894–1984) and one might easily wonder if the artist's works had a similar impact over a century later. Let's explore how Frampton used the colour red.

Marguerite Kelsey: the shoes

In Frampton's portrait of the model Marguerite Kelsey, our eyes are almost immediately drawn to her red shoes on the sofa. They contrast with the muted tones elsewhere. The model was measured for the dress and it was made by Frampton's mother. Frampton provided the red shoes. By drawing our attention to her feet up on the sofa we are being told that this is a relaxed pose, probably needed as the artist required Kelsey to sit for him at least a dozen times.

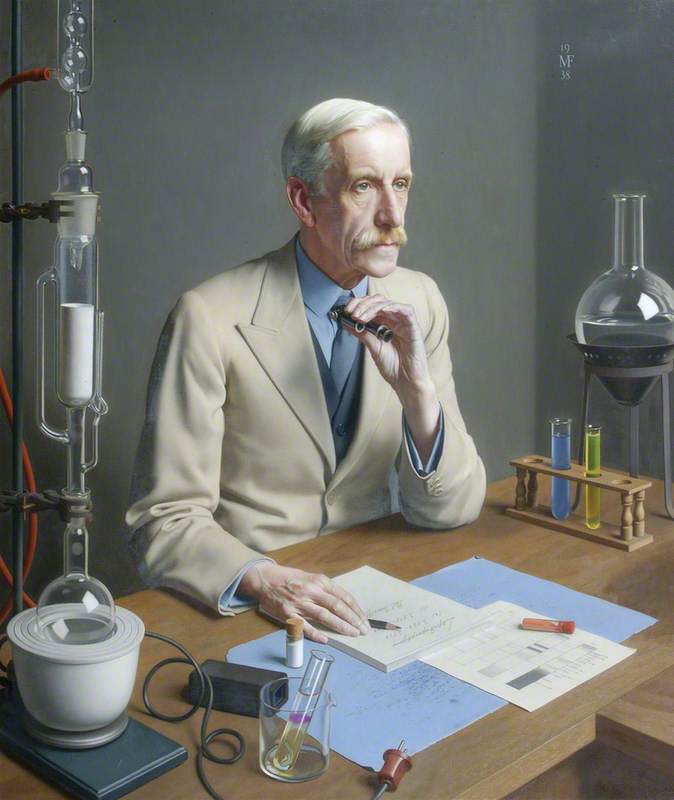

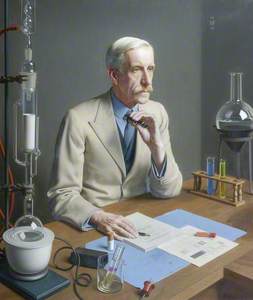

Sir Charles Grant Robertson: the weed-killer

© the artist's estate. Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

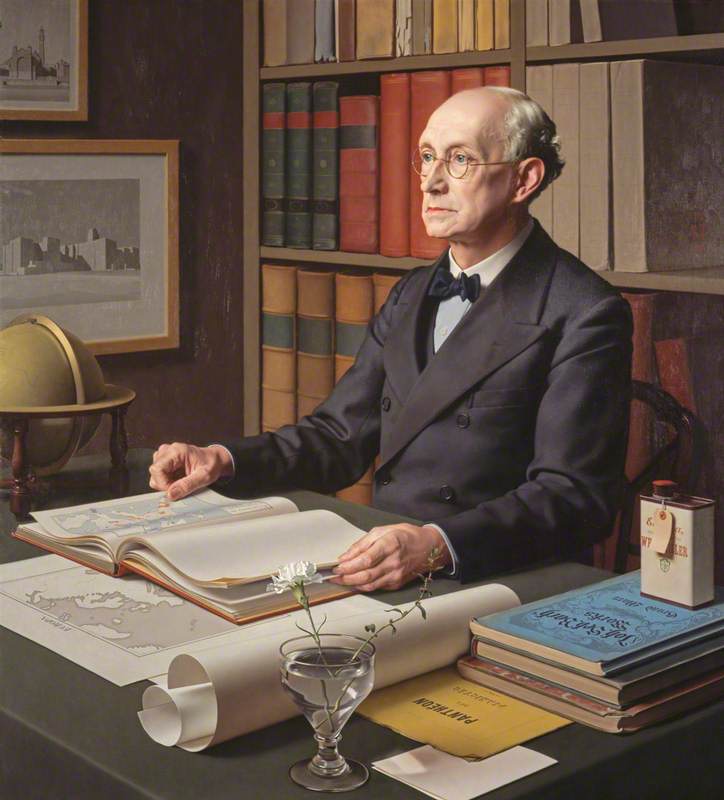

Sir Charles Grant Robertson (1869–1948), Historian 1941

Meredith Frampton (1894–1984)

National Galleries of ScotlandFrampton painted this portrait to mark the retirement of Sir Charles Grant Robertson as Principal and Vice-Chancellor of Birmingham University. Red here is used to draw our attention away from Robertson himself to focus on two of Robertson's passions, which he would have more time for in retirement.

The red books on the bookshelves and the visible red spine of the open book on his desk highlight Robertson's historical atlases that he published. Even more subtle however is the red tin lid and lettering, partially obscured by a label, of weed killer sitting on top of music books in the bottom right-hand corner of the painting. Robertson was a keen gardener. Pity the white flower in a glass of water!

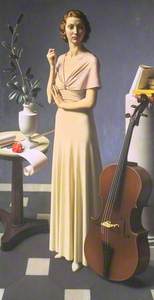

Margaret Austin-Jones: the camellia

This painting was painted as a relaxation for Frampton after a series of commissions. The model was Margaret Austin-Jones. Her elongated figure, accentuated by the folds in her dress are simultaneously set up in contrast to the rounded curves of the cello but also as an echo of the strings.

The red that draws the eye first this time is the camellia flower on the scroll of the table, bringing us to note the bow beside it, and then on to two smaller red echoes in the painting – the book against which the scroll of the cello rests, and then almost not seen at all the red on two of the strings below the bridge.

Frederick Gowland Hopkins: the phial

Red is made to compete with other colours in other portraits by Frampton. The large light blue sheet of paper on the desk of Frederick Hopkins, who served as President of the Royal Society up to a few years before the portrait, is echoed within his pale blue shirt and the blue liquid in the test tube on the right.

The little red phial sits on an important paper Hopkins is focussed on, whilst the red rubber tubes to the extra left hooked up to the biochemist's apparatus hardly get a look in at all. Hopkins discovered vitamins, and it is tempting to view the colouring as echoing the colouring in molecular models, where oxygen is red and nitrogen is blue.

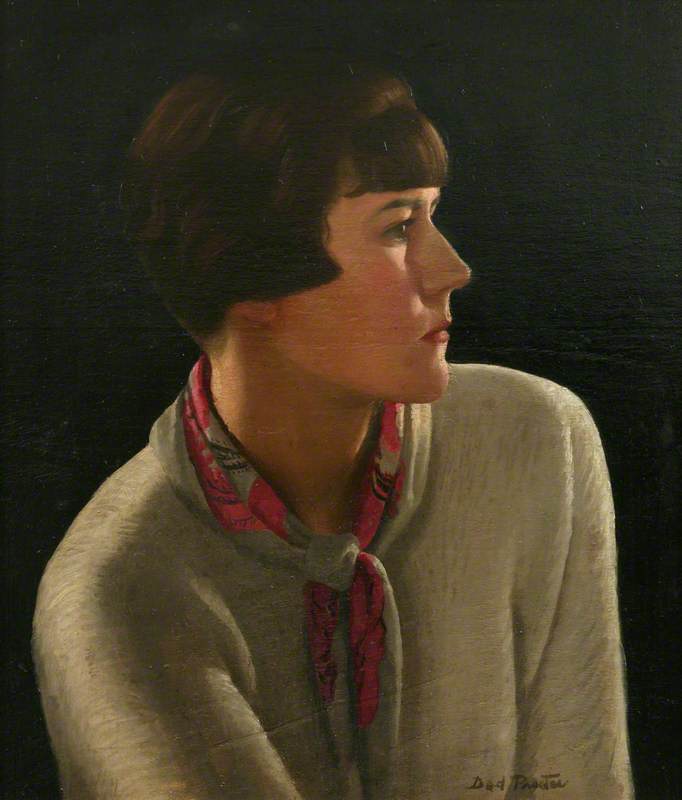

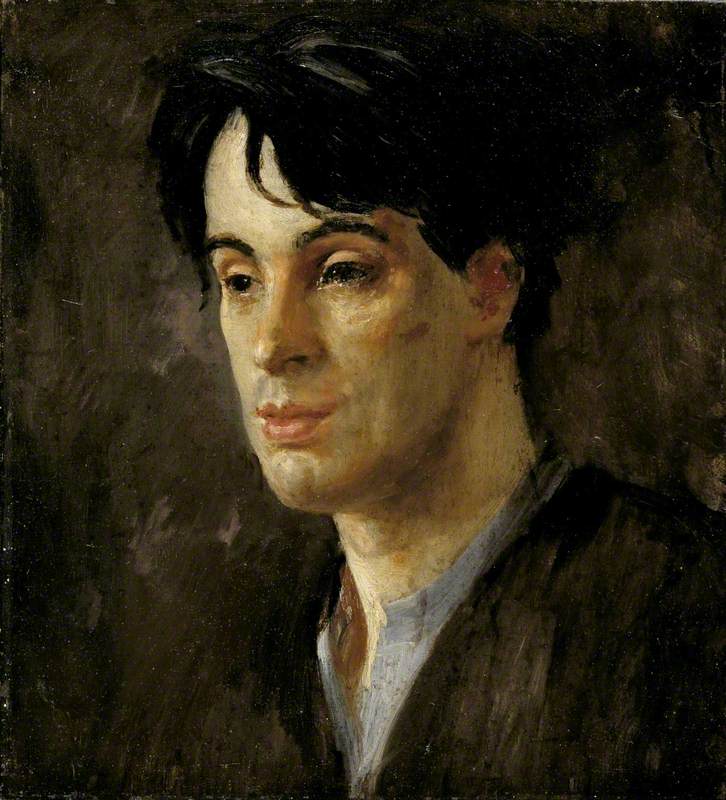

Lady Edith Bland-Sutton: the monocle ribbon

© the artist's estate. Image credit: The Royal College of Surgeons of England

Lady Edith Bland-Sutton (1865–1943)

Meredith Frampton (1894–1984)

The Royal College of Surgeons of EnglandLady Bland-Sutton was a friend of the Frampton family. Meredith Frampton's sculptor father, George Frampton, had sculpted a bust of Lady Bland-Sutton's surgeon husband in the early 1920s. In this portrait bequeathed to The Royal College of Surgeons, Frampton uses red as a directional device to lead the viewer's eye down to the monocle, which would be otherwise unnoticed, held in Lady Bland-Sutton's right hand.

Still Life: the poppy and measuring tape

In a painting predominantly set with grey and muted tones, the red poppy amongst the flowers growing in the vase and the red measuring tape draw the eyes in different directions. The poppy is very much alive, part of the natural world, but it is set in a broken urn, often seen in Victorian cemeteries as one of the stock symbols for death, and the contrasting masonry slabs behind the urn recall headstones.

Could the poppy also be a symbol of remembrance after the war? The disc of the measuring tape is echoed in the sawn tree trunk. Above it another tree has been more abruptly severed, recalling images of bomb-blown trees from the First World War.

Sir Henry John Newbolt: the book

Sir Henry Newbolt was a poet, novelist, historian and government adviser. He appears deep in thought in this portrait, and one might conjecture if it captures him a moment after reading something from two bookmarked pages in the slim red book on his lap he is resting his hands on. Frampton again includes scrolled paper on his desk, echoing the scroll armrest of his chair.

There is a further nod to red in the terracotta statue in the background. It is the figure of Aphrodite from the hall of the Athenaeum Club in London of which both artist and sitter were members, and is a replica of an antique original in the Louvre.

Margaret Austin-Jones: the belt

The red belt or waistband on the model's dress here draws the eye away from the regard of the subject down to the game of patience in the lower half of the table. Does it set up any expectation in terms of the model holding a red King of Diamonds or King of Hearts, so making a pair in patience?

There is a secondary red note on the table in terms of the budding red flower next to an ear of wheat, so angled to draw your gaze out from the room to the small strip of painted landscape background, where a red wagon or caravan sits at the edge of a harvested field.

Winifred Radford: the birdcage

The birdcage that the singer Winifred Radford holds could easily be lost against the hills and mountains in the background if it was not for the red handle (and contrasting white bird) that again leads you away from looking at the portrait to the rest of the painting.

Sir Ernest Gowers: the telephone

Image credit: IWM (Imperial War Museums)

Meredith Frampton (1894–1984)

IWM (Imperial War Museums)Right at the centre of this triple portrait of Sir Ernest Gowers and two colleagues in the South Kensington Control Room – where wartime civil defence operations across London were co-ordinated – is a red telephone. There is also a cream-coloured phone, a black phone and a third dangling cable hiding another phone (of a different colour maybe?).

The red phone just relates to the central Westminster area marked in red and the number one on the map behind Gowers. Everything does seem to be colour-coded – from the chart of the 'Disposition of Reserves' showing the same area, to the red pencil held by Gowers' colleague (who has the red phone) – and finally in the tiny red map pins just visible in front of the milk bottle.

David Saywell, Director of Digital Assets at Art UK

This content was supported by the Christie's Education Trust

![]()