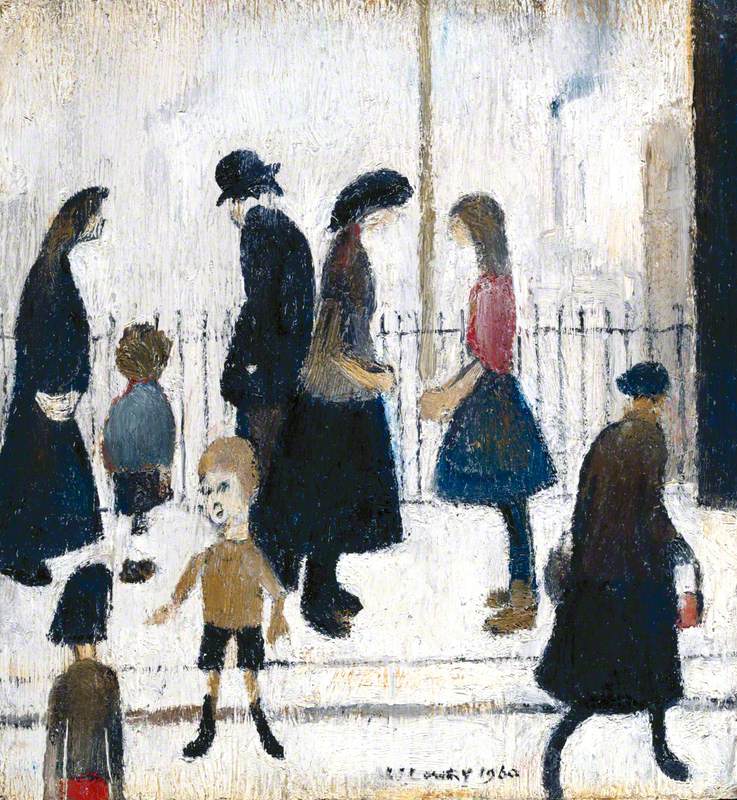

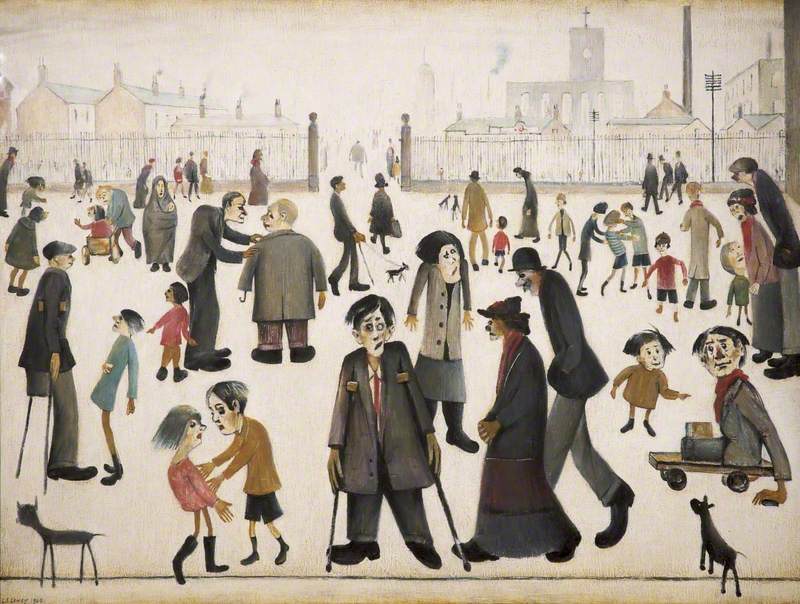

As the recent film Mrs Lowry & Son reminds us, L. S. Lowry's choice of style and subject matter was not always well received, even by his own mother. Lowry's dedication to scenes of everyday working life in northern England and (later in life) Wales, was certainly unique – as was the manner in which he painted them.

On the other hand, the legend of Lowry as the ultimate artistic outsider does need readdressing. Though he was never a member of the art establishment, Lowry was never completely out of touch with the art world either. Nor was his awakening to the artistic potential of the industrial landscape as exceptional as he liked to think it was.

One name that is hardly ever linked to that of L. S. Lowry is that of the artist, critic and art administrator Charles John Holmes (1868–1936), better known as C. J. Holmes. You can understand why: Holmes was, after all, from a very different background – educated at Eton, Holmes co-edited The Burlington Magazine in the 1900s, and rose to become Director of the National Portrait Gallery in 1909 and The National Gallery in 1916. But before looking at his works, let's look back a little further.

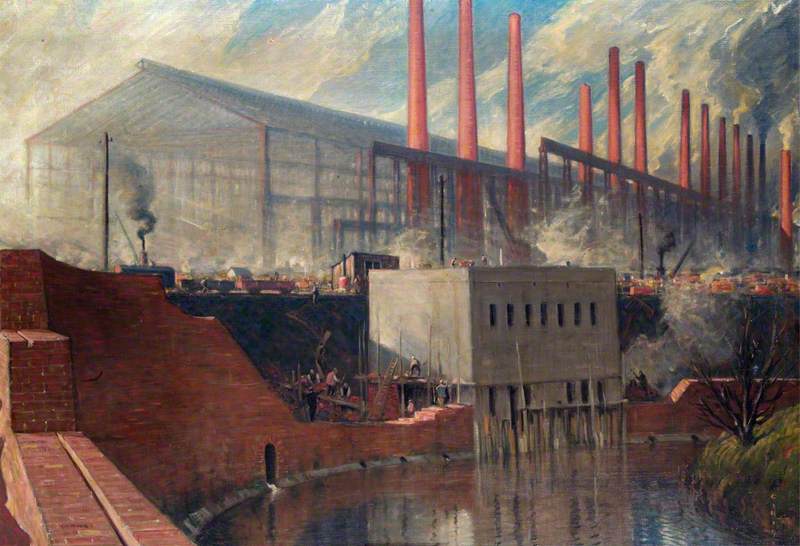

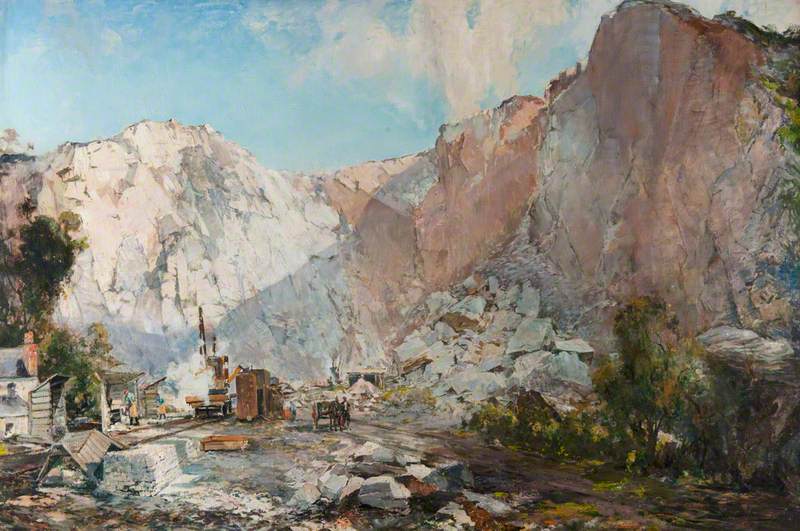

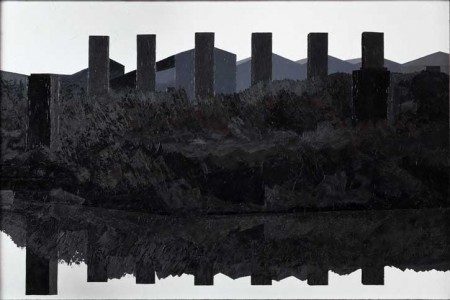

Industrial Scene

(South Hetton Colliery, near Sunderland) 1833

John Wilson Carmichael (1799–1868)

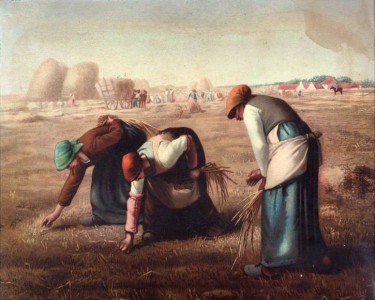

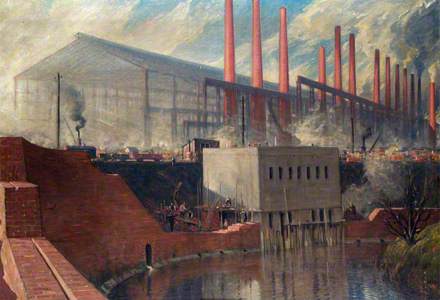

As Francis Klingender and others have shown, there is a rich history of artists responding to the industrial landscape from the eighteenth century onwards. Quarries, mines, pit-heads, forges and factories: all these have long appeared in British art (see John Wilson Carmichael's Industrial Scene of 1833, for example).

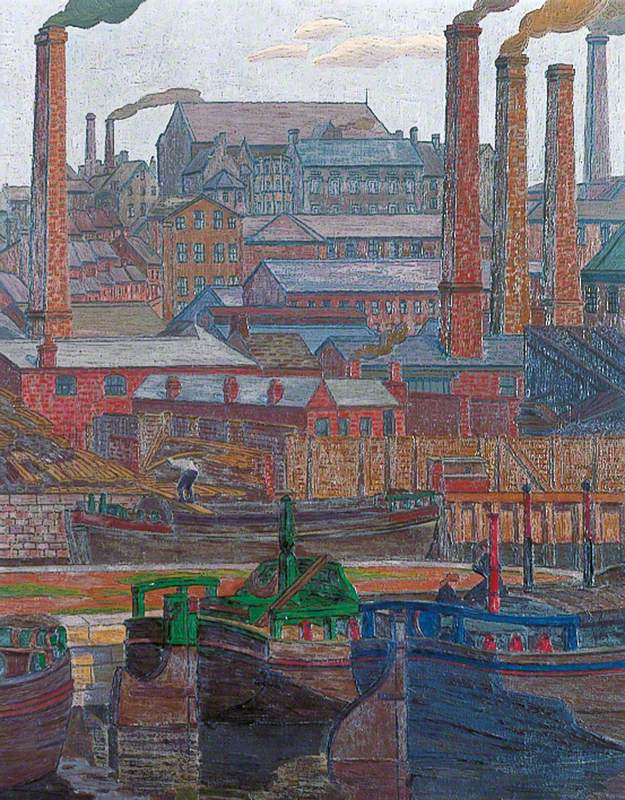

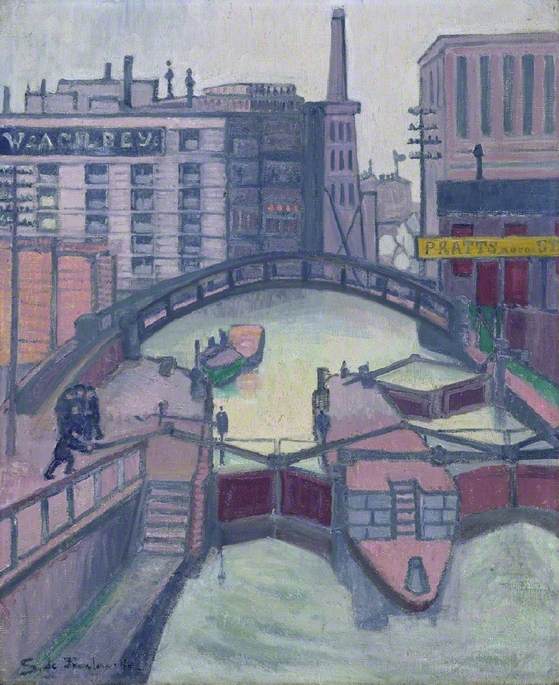

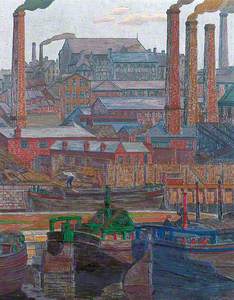

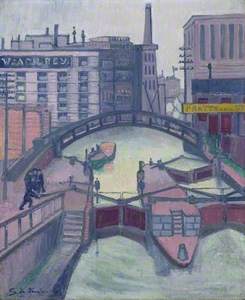

And while they were hardly a common feature of the artistic landscape during Lowry's emergence in the 1920s, there were some prominent early twentieth-century examples: think of Charles Ginner's Leeds Canal and Stanislawa de Karlowska's Lock on the Canal, for instance, or the eerie cityscapes of Algernon Newton.

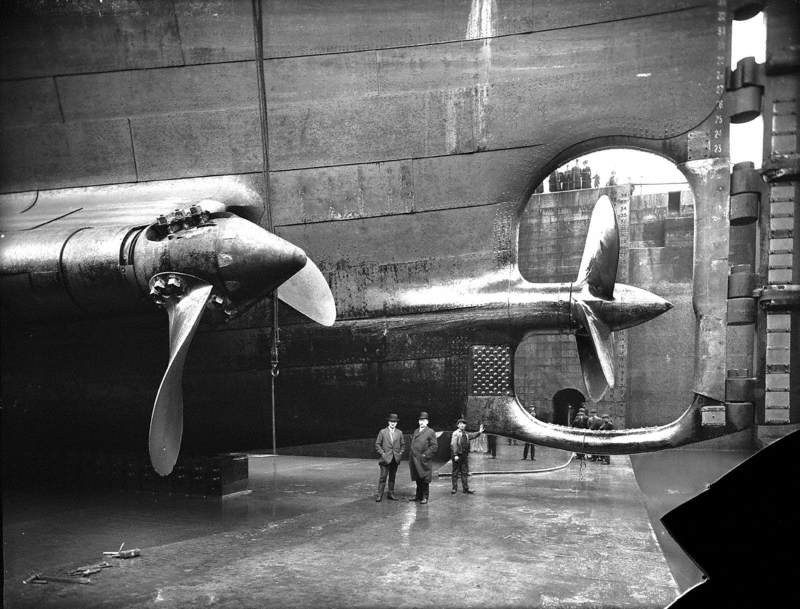

Printmakers such as Joseph Pennell and Muirhead Bone, meanwhile, specialised in images of urban industry and labour; the former publishing a whole book of drawings, etchings and lithographs in 1916, entitled Pictures of the Wonders of Work. Although it is possible, as suggested by the recent retrospective at the Tate, that Lowry was inspired by late nineteenth-century French precedents (such as Georges Seurat), it's just as likely that he was aware of an immediate British context for his work.

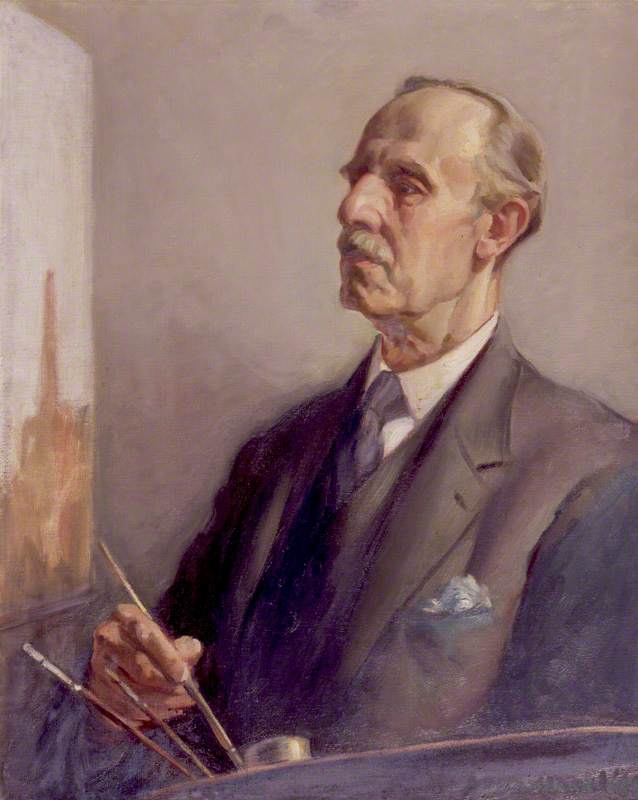

This is where C. J. Holmes comes in. He was the Director of the National Portrait Gallery and The National Gallery, and he was an expert on Constable, Rembrandt and the Japanese printmaker Hokusai – as well the first (and I imagine, only) person to write a book that draws parallels between the behaviour of fish and the Italian Renaissance (The Tarn and the Lake, published 1913).

Yet Holmes was also one of the keenest chroniclers of the early twentieth-century industrial landscape. In 1919 he held a whole exhibition dedicated to the subject at the Carfax Gallery in London. His sketchbooks, now in the collection of the British Museum, contain hundreds of sketches of northern cities such as Sheffield, Blackburn and Preston.

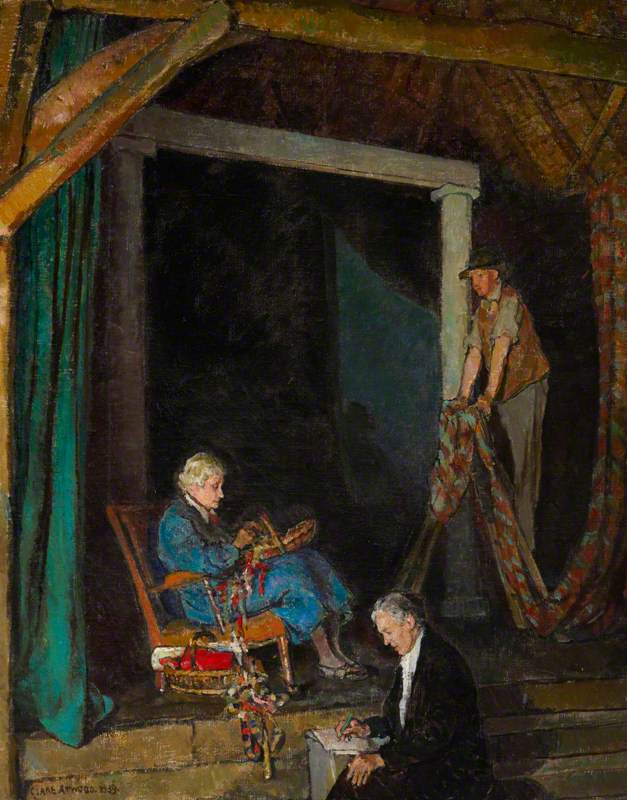

The industrial scene was clearly central to Holmes's identity as an artist: when George Holland painted his portrait of Holmes in 1934 he captured him at work on what appears to be a painting of a mill or factory.

There are several examples of Holmes's industrial landscapes in public collections on Art UK, including one of his earliest industrials, a 1907 painting of Wood Lane Power Station in London.

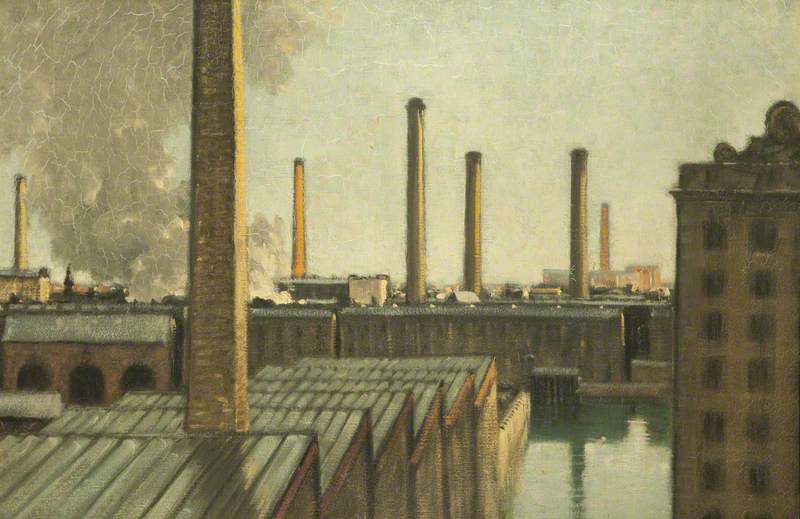

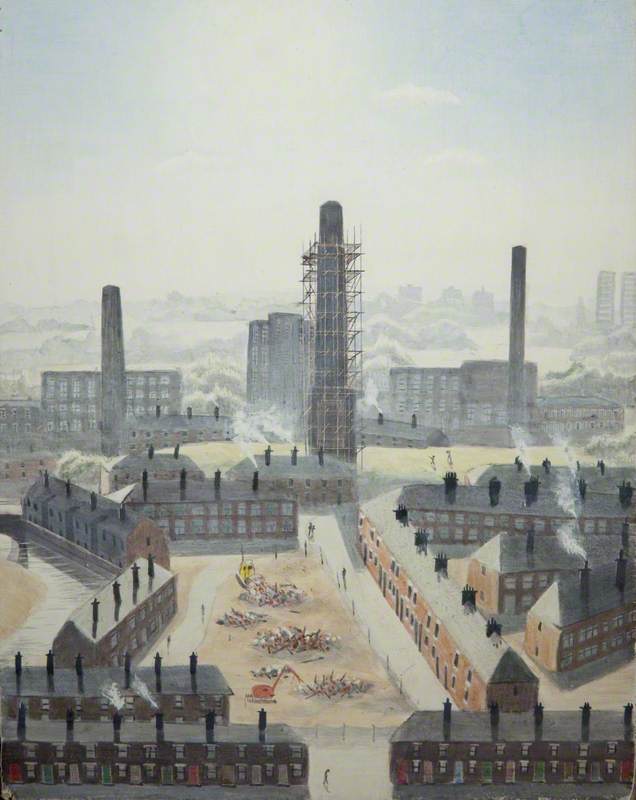

The atmospheric sky we see here is a long way from Lowry's dull white backdrops; nevertheless, the firm black outlines given to the buildings and chimneys below suggests a shared interest in the rigid geometry and monumentality of industrial buildings.

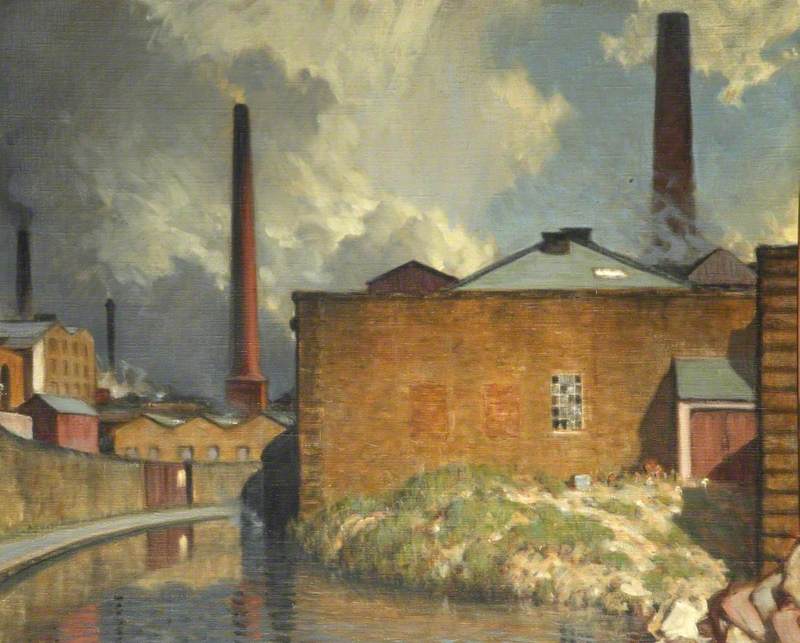

This same outline – and evident fondness for angular forms – appear again in later works by Holmes, including the bold Industrial Landscape, now at Leeds, and the stark Seven Chimneys at Blackburn.

The second work offers a clue as to what attracted Holmes to these landscapes in the first place. The seven chimneys represented here form part of the landscape of Preston, the city in which Holmes was born. Although he was not born into a working-class family (his father was a vicar, his mother the daughter of a local solicitor), he was very familiar with the working landscape. He used to fish in the canals as a child and climb the factory roofs. The views from there made a huge impression on him, and he never tired of returning to the subject.

Although Holmes did not pursue art full-time (his museum director roles didn't allow for that), and although he never again lived in the industrial north, his sketchbooks suggest that this was more than a passing interest for him.

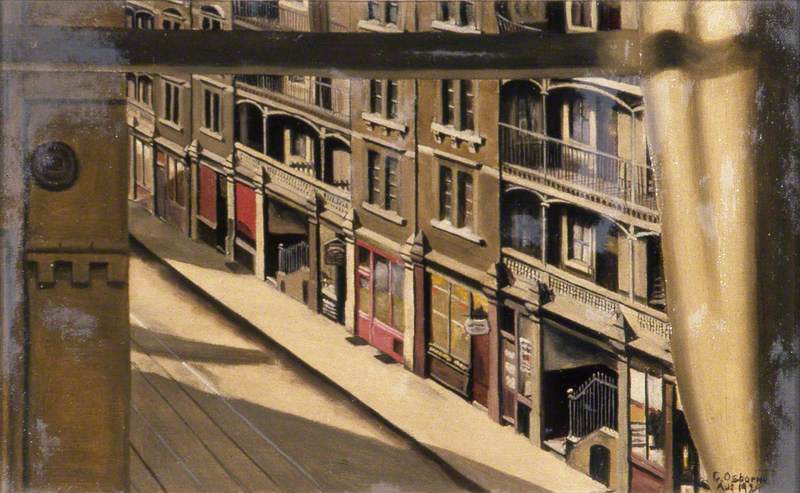

During the First World War he picked up work painting steel factories in Sheffield, and in the late 1920s, he accepted a commission from a friend to paint a series of Blackburn cityscapes. Most of these can now be found at Samlesbury Hall in Lancashire, though The Yellow Wall, Blackburn, now at Liverpool's Walker Art Gallery, may also be an outcome of this project.

This final painting is typical of Holmes's work. The focus of the painting is a surprising one, centred as it is on an expanse of plain red-brick wall. Two windows seem to have been bricked in; a third contains several panes of smashed glass. As often with Holmes's work, the landscape is not populated. This may be partly due to a lack of confidence with the human figure (Holmes was never a talented figure painter), or to Holmes's tendency, perhaps a feature of his class background, to overlook the human aspect of the industrial scene. The scene could be depressing, but the warm sunlight hitting the old red bricks, the curve of the canal, and the mingling of the chimney smoke with the gathering clouds up above, offer up something rather more charming.

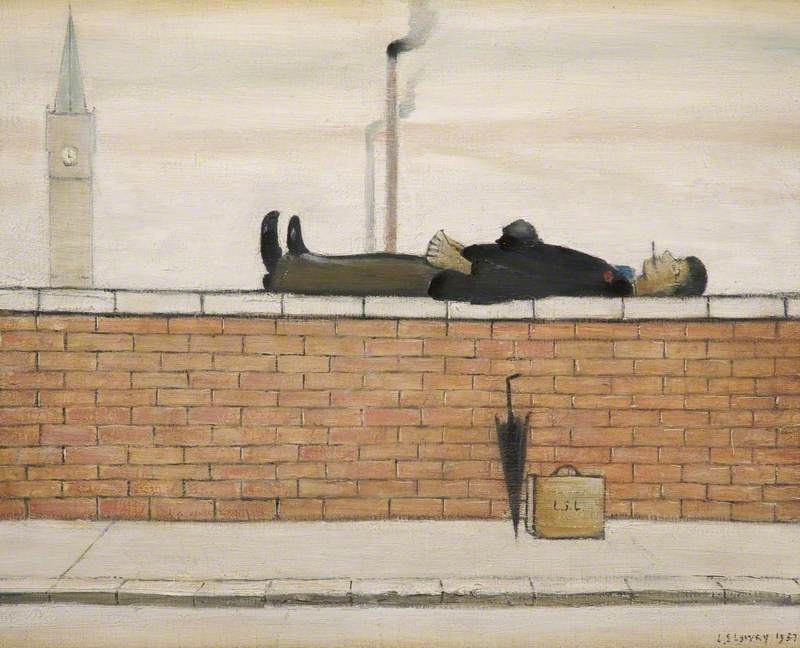

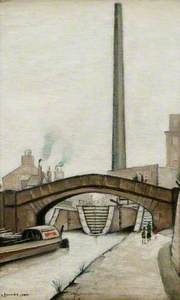

The lack of visible human activity makes it easier to enjoy the landscape – and to forget the potentially negative impact of heavy industry on the bodies and minds of those who worked there, and on the wider environment. Holmes, like Lowry, knew how to extract beauty from unexpected places (compare, for example, Lowry's Canal Bridge, painted only 12 years later).

Unlike Lowry, however, he paid little or no direct attention to the communities that existed within and beyond the factory walls.

Were Holmes and Lowry aware of each other? Lowry's career only really took off after Holmes's death, and Lowry always claimed that no one painted the industrial scene 'seriously' before he took it up. Had he ever encountered Holmes's paintings or drawings, it is possible that Lowry would have noted the absence of the human figure, and the privileging of atmosphere over incident. Yet he might also have noted, with admiration, Holmes's dedication to the subject, and resistance to high drama.

If there's ever an exhibition celebrating the humble red-brick wall (and there should be), there's no doubt that both artists should be included. There's less visual human activity in Holmes's paintings than in Lowry's, but The Yellow Wall, Blackburn is haunted by humans. This wall, Holmes seems to suggest, has as many stories to tell as those of any castle ruin, or Roman remains (the like of which he also painted).

Lowry, surely, wouldn't have argued with that.

Samuel Shaw, University of Leicester, co-founder of the Edwardian Culture Network