Eduardo Luigi Paolozzi – artist, sculptor, writer – was born 100 years ago, in March 1924. A major figure in post-war British art, he was born and raised in Leith, Edinburgh, before eventually settling in London, where he mainly lived and worked until his death in 2005 at the age of 81.

Throughout his career, Paolozzi combined working as an artist with teaching in British art colleges, as well as institutions in Germany and America. Highly versatile, he was a sculptor, printmaker, collagist, ceramicist, filmmaker, designer and writer as well as a passionate collector of all kinds of artefacts.

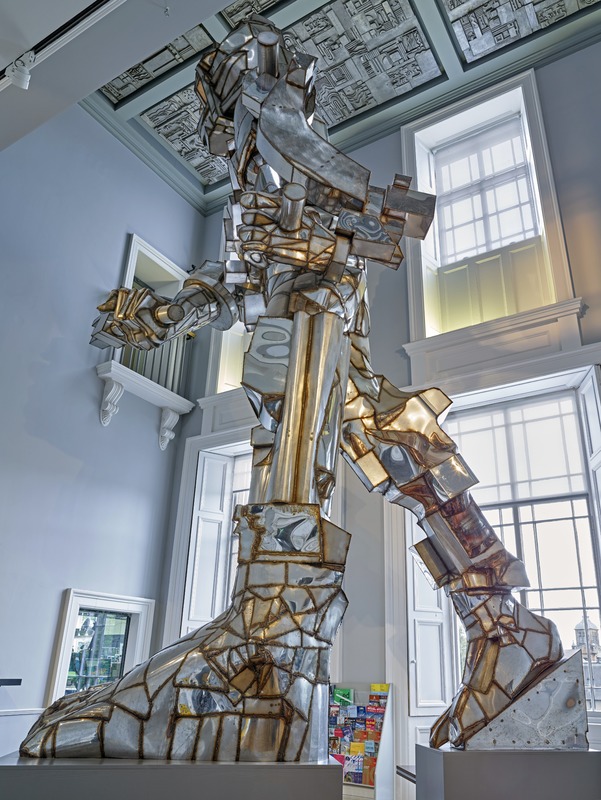

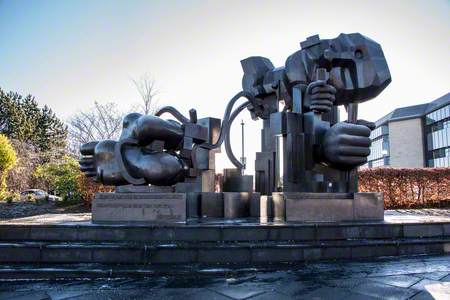

The Wealth of Nations

1992–1993

Morris Singer Art Foundry Ltd (founded 1927) and Eduardo Luigi Paolozzi (1924–2005)

By the end of his life, Paolozzi had become one of Britain's best-known sculptors, having taken on a number of large-scale commissions across the UK, such as Master of the Universe and his colossal work The Wealth of the Nations, both of which are located in Edinburgh.

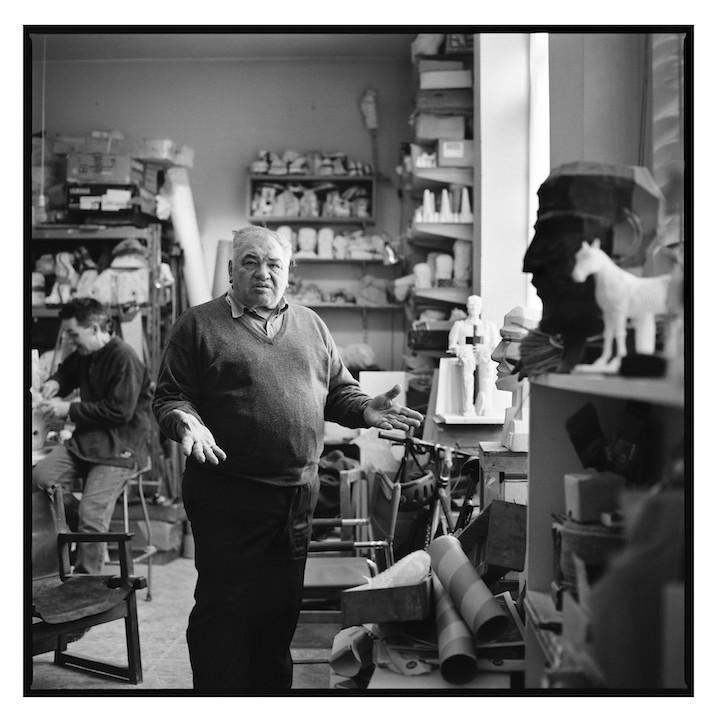

In 1994, Paolozzi donated the entire contents of his Chelsea studio to the National Galleries of Scotland, and the studio space was meticulously recreated at the Dean Gallery in Edinburgh (now Modern Two) with sculptures, models, books, toys and even a bed to rest in.

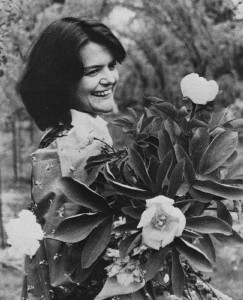

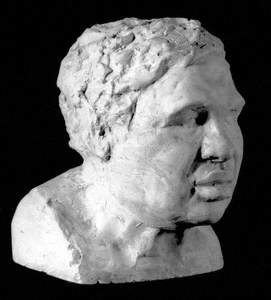

Eduardo Paolozzi (1924–2005)

1999/2003, photograph by Debra Hurford Brown

The gallery opened in 1999 with the purpose of storing and displaying Paolozzi's work alongside an impressive Dada and Surrealism collection. To celebrate the centenary, the gallery is currently hosting the exhibition 'Paolozzi at 100'.

The eldest child of Italian immigrants Alfonso and Carmela Paolozzi, the artist's family ran a confectionery shop in Edinburgh's Albert Street.

They suffered a terrible tragedy in 1940, when his father and maternal grandfather were taken as prisoners to be interned in Canada during the hostilities towards Italians in the Second World War. The ship they boarded – the SS Arandora Star – was torpedoed and sunk off the west coast of Ireland by a German submarine, killing more than 800 on board.

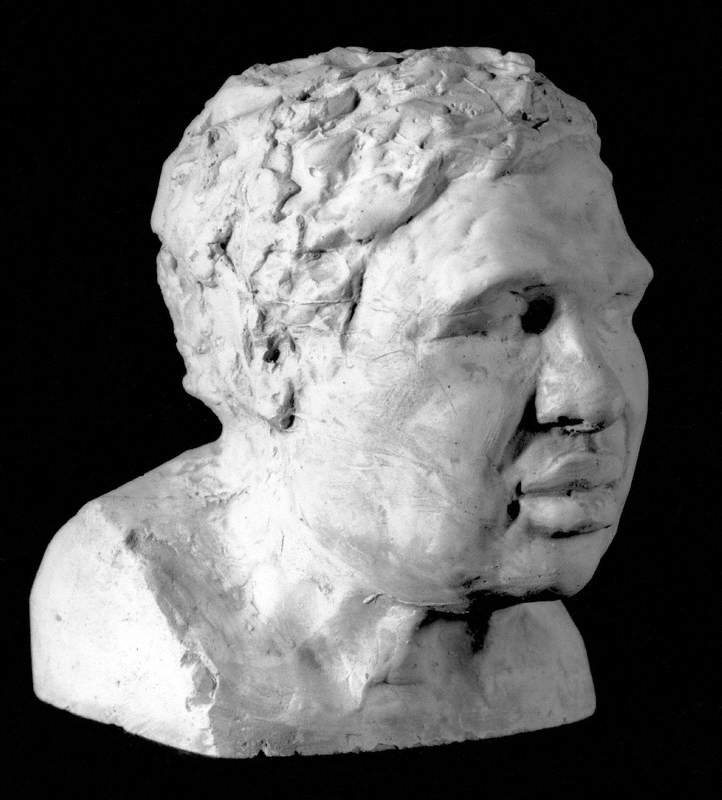

Sir Eduardo Paolozzi (1924–2005)

1987

Eduardo Luigi Paolozzi (1924–2005)

Paolozzi, too, was interned for three months and, after his release, returned to work at the family shop, later leaving school to work as a mechanic. In 1941, he enrolled for evening classes at Edinburgh College of Art, where he began studying full-time in 1943.

These early years of study were interrupted by the ongoing war, and that same year he was called up for military training in England. While there, he managed to attend classes at Central Saint Martins in London and, after being discharged in 1944, studied at the Ruskin School of Drawing, then the Slade School of Fine Art.

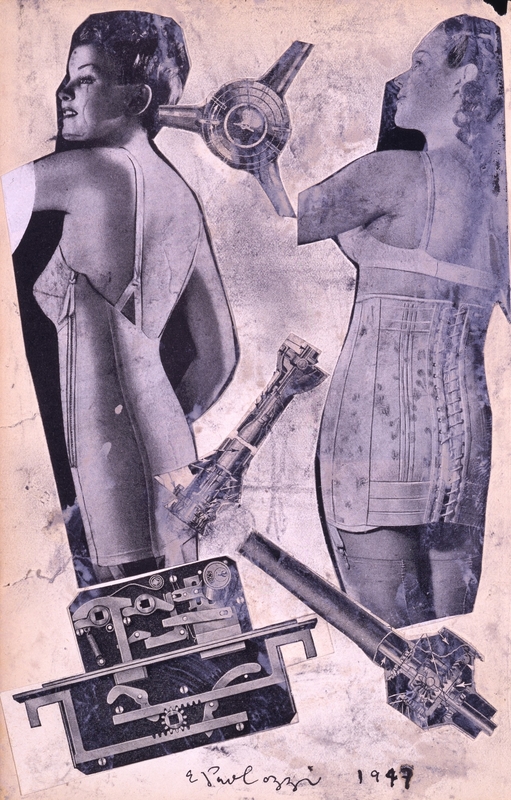

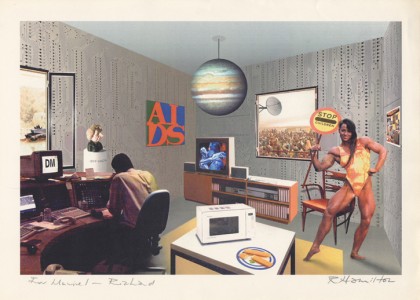

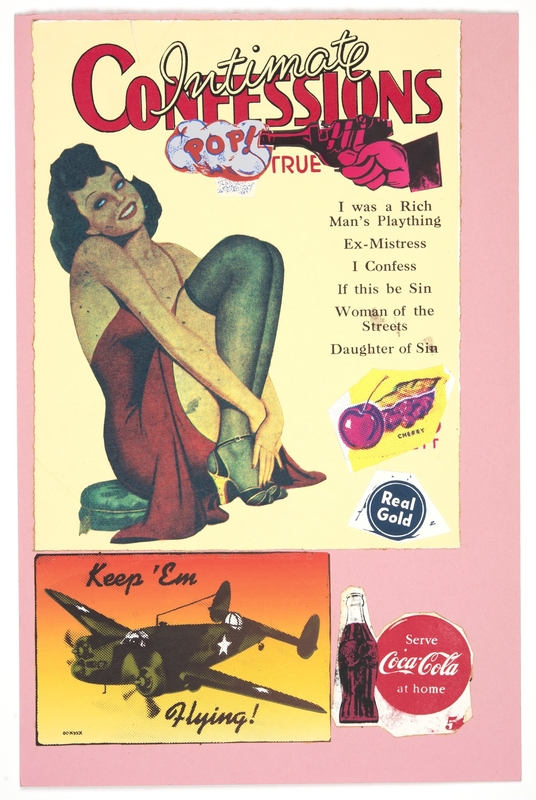

In the mid-1940s he began working in collage, using printed images from books and magazines, and this remained a constant interest throughout his long career.

Paolozzi's first exhibition of drawings and sculptures took place in 1947 at the Mayor Gallery in London while he was still a student. Its success enabled him to travel to, and live in, Paris until 1949. Enrolling at the École des Beaux-Arts, he had the chance to meet and see work by artists such as Alberto Giacometti, Constantin Brâncuși, Max Ernst and Jean Arp.

Paolozzi is considered an early pioneer of Pop Art and is often referred to as the father of British Pop Art. His interest in Surrealism paved the way for his unique brand of collage and printmaking, and Paris provided the ideal opportunity to learn more about Surrealism, which was at its height in the 1930s. Meanwhile, the influence of the sculptors he met is apparent in works such as Paris Bird.

In 1948, Paolozzi received an invitation to teach sculpture at the Central School Of Art and Design in London. Deciding to stay on in Paris, he took up the post the following year and remained there until 1955. He married textile designer Freda Elliott in 1951 and they had three children, divorcing in 1988.

His friendship with artist and photographer Nigel Henderson – whom he met while studying at the Slade – proved influential in his early years as an artist, and in 1952 they were among the founders of the Independent Group (IG).

Paolozzi was passionate about mass culture as well as science and technology, and this radical group of young artists, writers and critics, who met at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London, aimed to challenge the dominant modernist culture of the time with a view to making it more inclusive of popular culture.

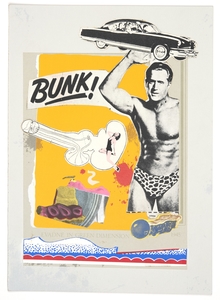

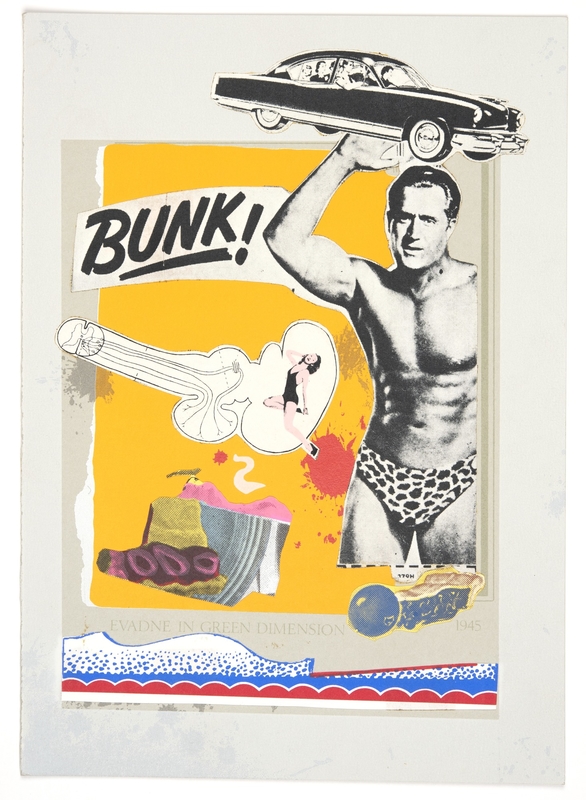

1. Evadne in Green Dimension (from 'Bunk')

1972

Eduardo Luigi Paolozzi (1924–2005)

Other artists involved included Richard Hamilton, John McHale and William Turnbull. The IG also included critics and architects, such as Alison and Peter Smithson. Also in 1952, Paolozzi gave his groundbreaking Bunk! lecture at the ICA.

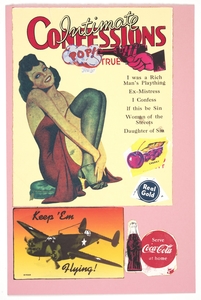

This featured a collection of images from glossy and pulp magazines he had amassed in the process of creating scrapbooks. Shown on a projector with no commentary, it was the first time such images had been treated as fine art, heralding the beginning of the British Pop Art movement.

25. I Was a Rich Man's Plaything (from 'Bunk')

1972

Eduardo Luigi Paolozzi (1924–2005)

Paolozzi's first international exposure also came that year, in the Venice Biennale of 1952. Selected to be shown in the British Pavilion exhibition 'New Aspects of British Sculpture' with Henry Moore as a mentor, Paolozzi and his seven contemporaries represented a new generation in British sculpture. Paolozzi exhibited work including a brass version of Forms on a Bow.

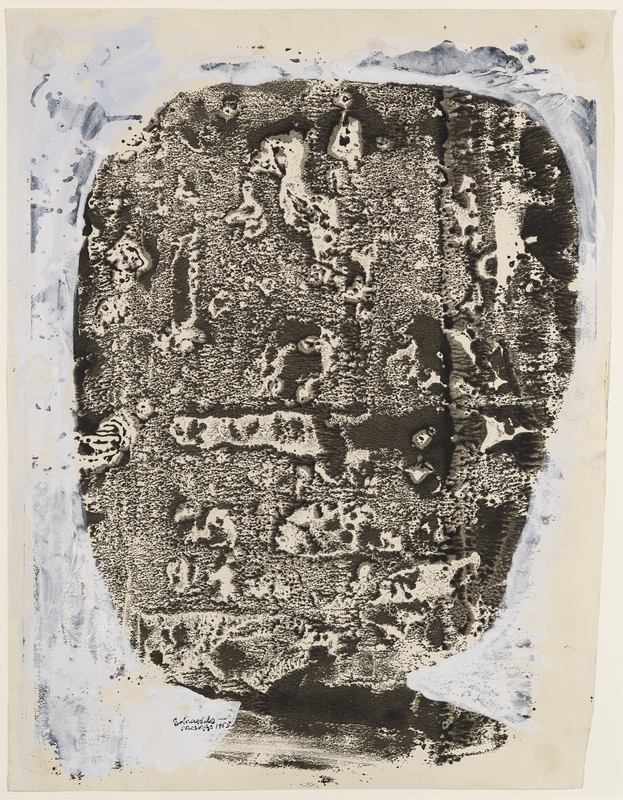

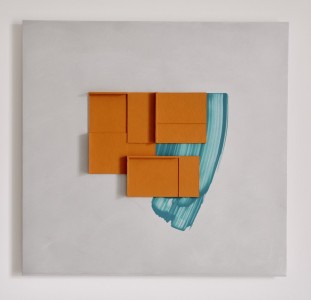

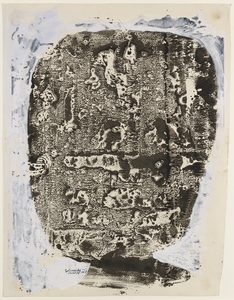

Paolozzi took a teaching post at Central Saint Martins in 1955, which coincided with the development of a new style of sculpture featuring reliefs of everyday, found objects, which he would use to create imprints, for example, Icarus.

The following year, Paolozzi exhibited in another groundbreaking exhibition – the Independent Group's 'This Is Tomorrow' at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, involving architects, artists, designers and theorists.

By the late 1950s, he was creating machine-like sculptures demonstrating the beauty of mechanical design, such as His Majesty The Wheel and Wittgenstein at Casino I.

Paolozzi met the art collector Gabrielle Keiller in the 1960s, and she became a significant patron of his for over a decade. Colour was becoming more present in his sculptures, and he also began to practise printmaking.

In 1971, the Tate Gallery, as it was called at the time, staged a large retrospective of Paolozzi's work – he was 47. It featured some of his ready-made casts, such as Crash Head, which harked back to Mr Cruikshank, a work created in 1950. There were also screenprints and a skip filled with offcuts of old sculptures.

For the next 20 years, he received several high-profile commissions, creating tapestries and ceiling panels for Cleish Castle in Kinross, and, in 1976, making a set of doors for the Hunterian Art Gallery in Glasgow. Another came from Transport for London in the early 1980s to create mosaics for Tottenham Court Road Tube station.

Tottenham Court Road Underground

1987

Eduardo Luigi Paolozzi (1924–2005)

Paolozzi was appointed Professor of Sculpture in 1981 at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Munich. His subject matter was returning to the human figure by the 1980s and 1990s.

Appointed a CBE in 1968 and elected a Royal Academician in 1979, Paolozzi was awarded the office of Her Majesty's Sculptor in Ordinary for Scotland in 1986, and received a knighthood in 1989.

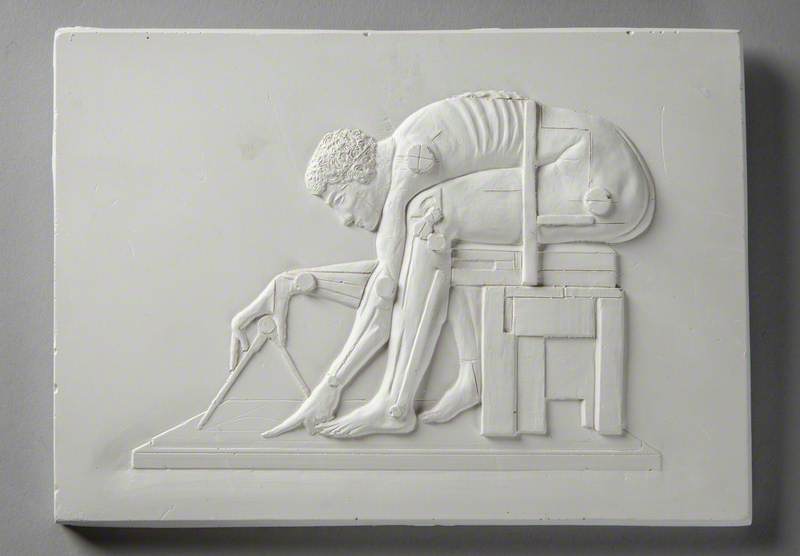

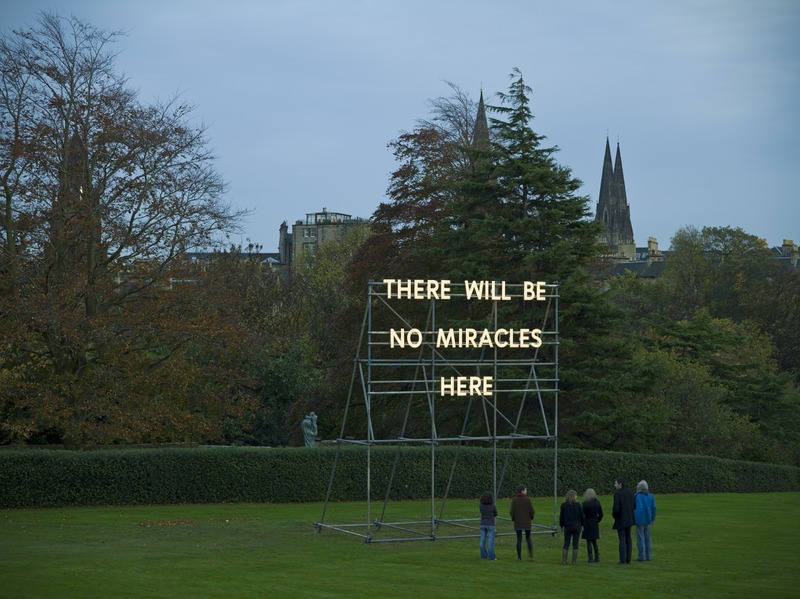

The connection between art and science greatly interested Paolozzi and a number of later works were based on William Blake's famous eighteenth-century depiction of Sir Isaac Newton, showing him measuring the universe.

Variations of these sculptures can be found across museum collections, with one of the best-known being Newton, outside the British Library in London, as well as Master of the Universe at Modern Two in Edinburgh.

Paolozzi is quoted as saying: 'I suppose I am interested, above all, in investigating the golden ability of the artist to achieve a metamorphosis of quite ordinary things into something wonderful and extraordinary.'

In an article written for Art UK by fashion designer and sculptor Nicole Farhi, she recalls of Paolozzi: 'He was always looking at buildings, windows, people, cars. His curiosity was insatiable; skips were his passion. Always excited to make a find, he would collect old debris or discarded scraps to take back to his studio. He would put them on his shelves next to his plaster casts or give them to his students.'

Paolozzi contributed to the artwork for the album 'Red Rose Speedway' by Paul McCartney and Wings, which was released in 1973. McCartney said of him: 'I once visited his Chelsea (London) studio and was impressed by his sense of humour, the twinkle in his eye and his generosity.'

Always keen to evolve his practices, and never losing his passion to consume information about the modern world, Paolozzi worked well into his 70s. He created the towering Vulcan for the opening of the Dean Gallery, where it almost touches the ceiling in the present-day café.

Paolozzi suffered a near-fatal stroke in 2001 and was wheelchair-bound until he passed away in April 2005, marking the end to a life filled with the pursuit of discovering the extraordinary in the ordinary.

Jennifer McLaren, freelance arts journalist based in Scotland

This content was supported by Creative Scotland

Further reading

Fiona Pearson, Eduardo Paolozzi, National Galleries of Scotland, 1999

Robin Spencer (ed.), Eduardo Paolozzi: Writings and Interviews, Oxford University Press, 2000