Mary Anning was born in 1799 to a working-class family who lived by the rugged coastline of Lyme Regis, Dorset. Despite her humble origins and lack of formal education, by the time of her death in 1847, she was well known across Europe and had established herself as one of the most important British 'amateur' palaeontologists and fossil collectors in history.

Although often dismissed or derided by her local community for her unusual lifestyle, Anning made significant contributions to the field of palaeontology, which are still recognised today. Historians have pointed out that due to the barring of women from academic institutions and journals, she did not always receive full credit for her work – her male peers often taking credit for her discoveries.

'The world has used me so unkindly, I fear it has made me suspicious of everyone.' – Mary Anning

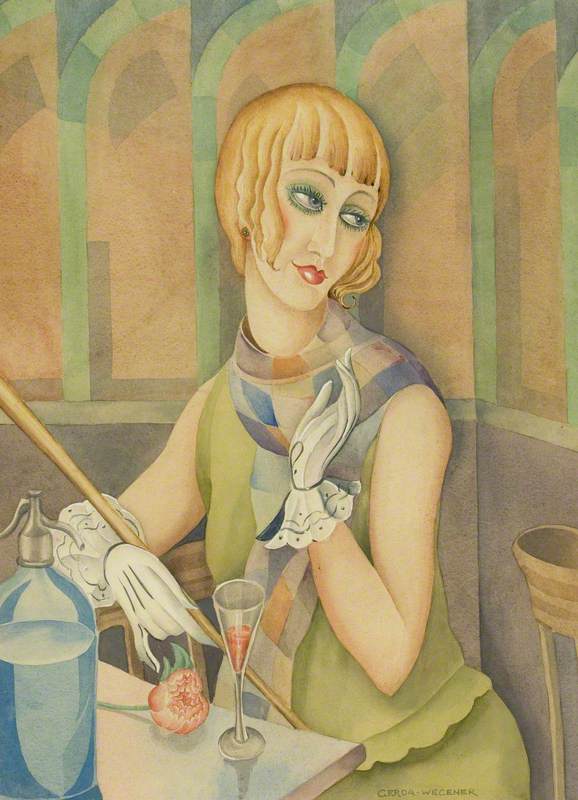

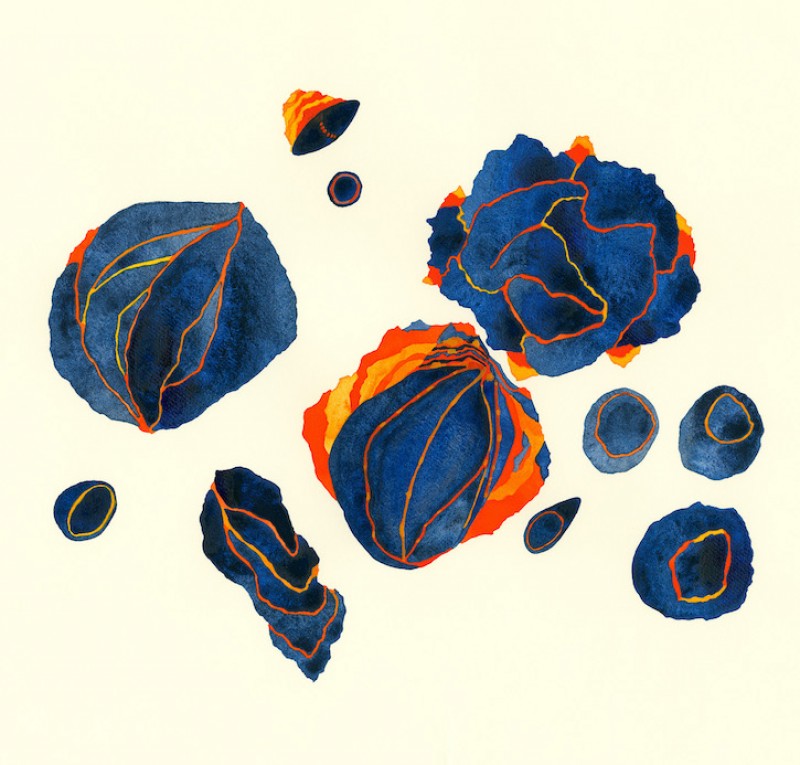

Still from 'Ammonite'

2020, film by Francis Lee

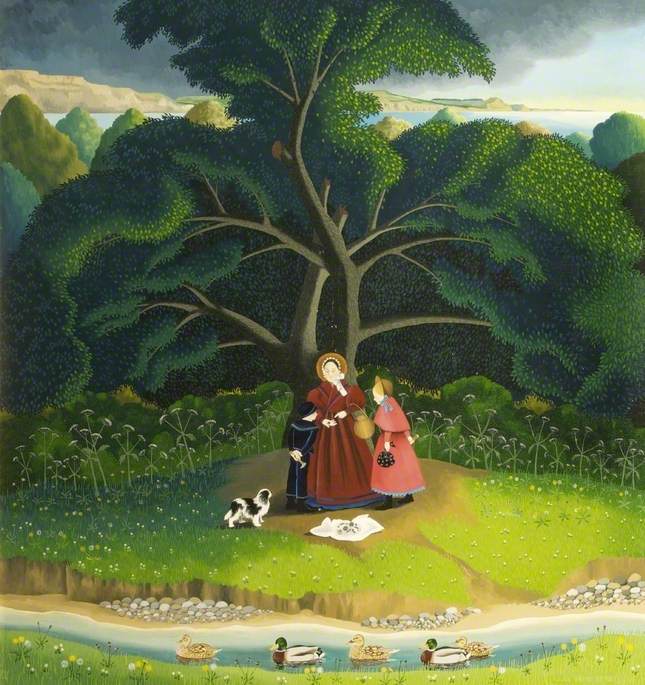

The 2020 film Ammonite, directed by Francis Lee, places Anning in the limelight. Anning is played by Kate Winslet, and Saoirse Ronan plays Charlotte Murchison (1788–1869), a wealthy yet melancholic British woman who in real life became a close friend of Anning's and also made significant contributions to geology and the study of fossils.

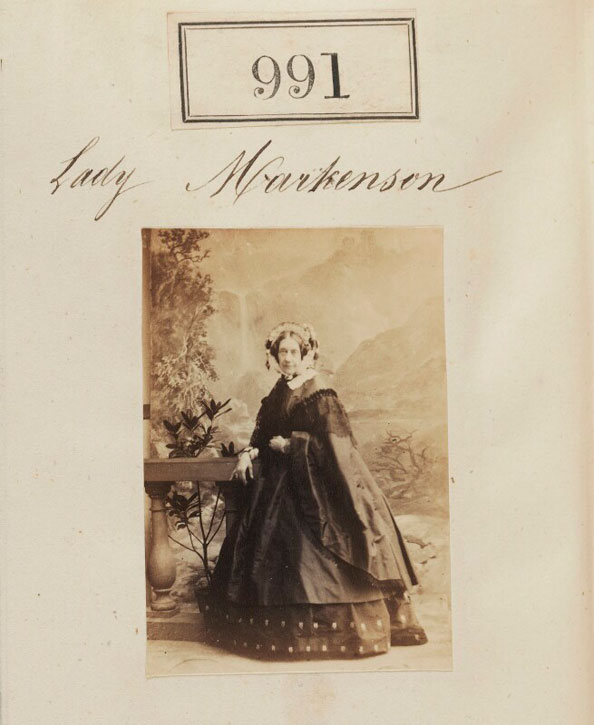

This photograph by Camille Silvy in the National Portrait Gallery shows Charlotte Murchison in 1860.

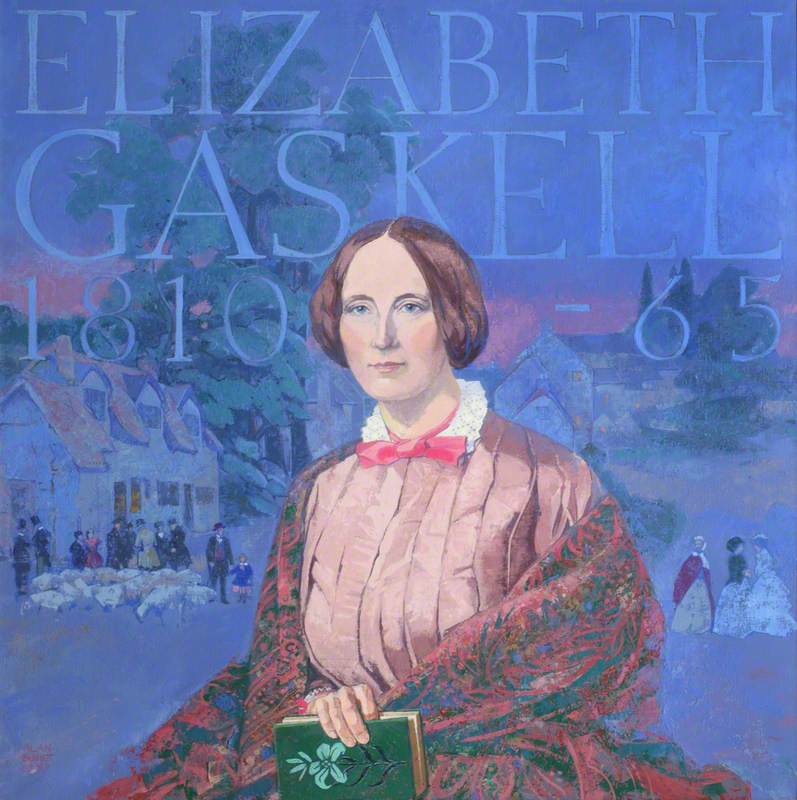

Charlotte (née Hugonin), Lady Murchison

1860, albumen print by Camille Silvy (1834–1910)

Like Anning, Murchison was fascinated with rock formations and geological life, becoming an expert in the subject alongside her well-known geologist husband, Roderick Impey Murchison.

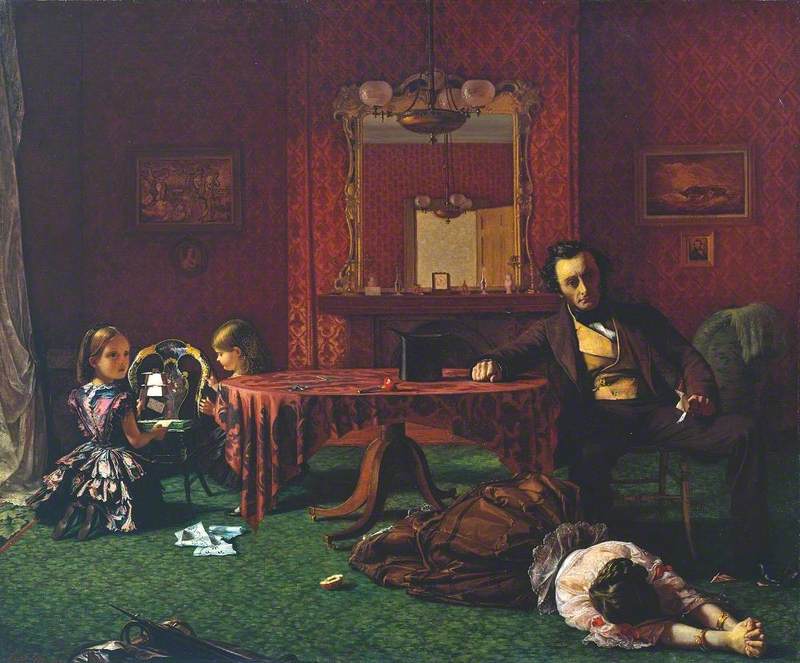

Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, 1st Bt

1856

Stephen Pearce (1819–1904)

Murchison created illustrations that were incorporated into many of her husband's publications, and she has even been credited with formulating some of his scientific ideas and theories.

In Lee's cinematic adaption, Anning and Murchison enter into a lesbian romance when Murchison's husband temporarily places her in the care of Anning; he hopes that her depression will subside after finding a hobby.

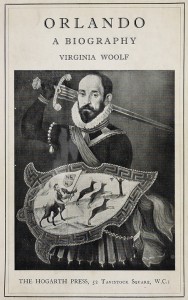

Although the love affair between the two women is a fictional take (or at least according to the insufficient evidence we have), it helps to raise questions about the broader obscuration of queer history, the oppressed desires of women, and the power of female intimacy during the nineteenth century.

Ammonite follows a trend in television and cinema, which brings to the surface hidden or neglected historic narratives about same-sex, forbidden female love, seen recently in Sally Wainwright's Gentleman Jack about the life of Anne Lister, and Céline Sciamma's Portrait of a Lady on Fire, a powerful contemplation on the female gaze.

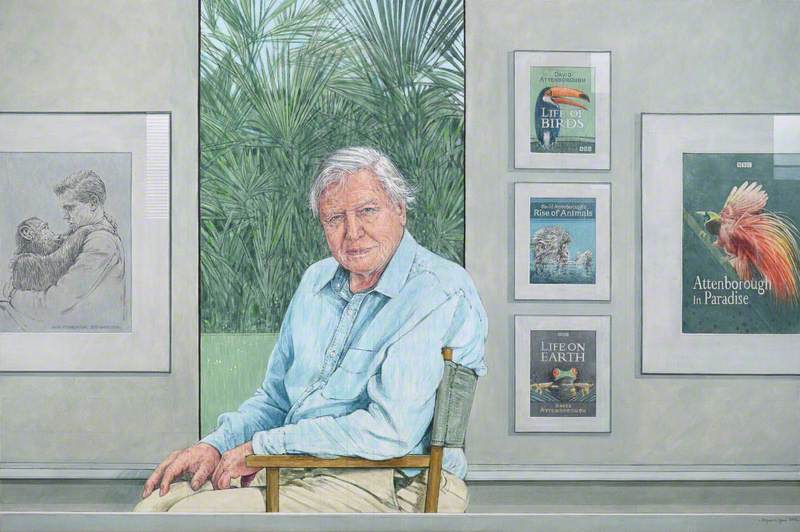

Anne Lister of Shibden Hall (1791–1840)

Joshua Horner (1811–1881) (attributed to)

A 'devoutly religious' woman according to her biographer Shelley Emling, Anning never married, which ignites speculation that she was, in fact, disinterested in men, or simply that she managed to support herself financially from her work. Whether Anning was queer or not is still up for debate (director Lee has received some critical backlash for inserting an LGBTQ narrative), though we know that she had close friendships with other women and, due to her unmarried status, most likely earned the title of 'spinster'. Such derogatory labels were often attached to unmarried women around this time, as a way to brand them as undesirable or, occasionally, used as a coded term to signify their sexual 'transgressions'.

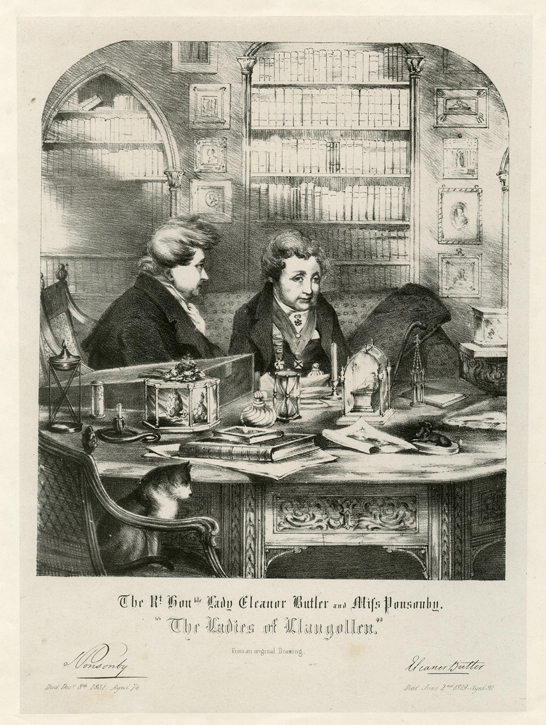

For example, the upper-class Irish spinsters Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby, known as the 'Ladies of Llangollen', were famous for the cohabitation and lesbian relationship in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Their relationship gave rise to terms such as a Boston marriage, to signify a platonic partnership, or cohabitation between two women, which in reality, was often a way to disguise a lesbian relationship, or make it respectable to nineteenth-century society.

But who was Anning, and how did her work as a fossil hunter revolutionise the field of palaeontology and beyond?

At the age of twelve in 1811, Anning discovered the first dinosaur skeleton – an ichthyosaur – while fossil hunting on the cliffs of Lyme Regis.

She sells sea shells on the sea shore...and also massive ichthyosaurs. Happy Birthday to Mary Anning who was born 220 years ago today. This was her first ichthyosaur, painstakingly dug up when Mary was 12. #MaryAnning #BOTD pic.twitter.com/gCBv8usBM6

— Digitising the NHM (@NHM_Digitise) May 21, 2019

As a child, she had been encouraged to search for and collect 'curiosities' by her father, Richard Anning, a cabinet maker and carpenter who began collecting fossils to supplement the family business. Anning would find fossils by walking up and down the seaside coasts, climbing cliffs, and digging in unexplored terrain.

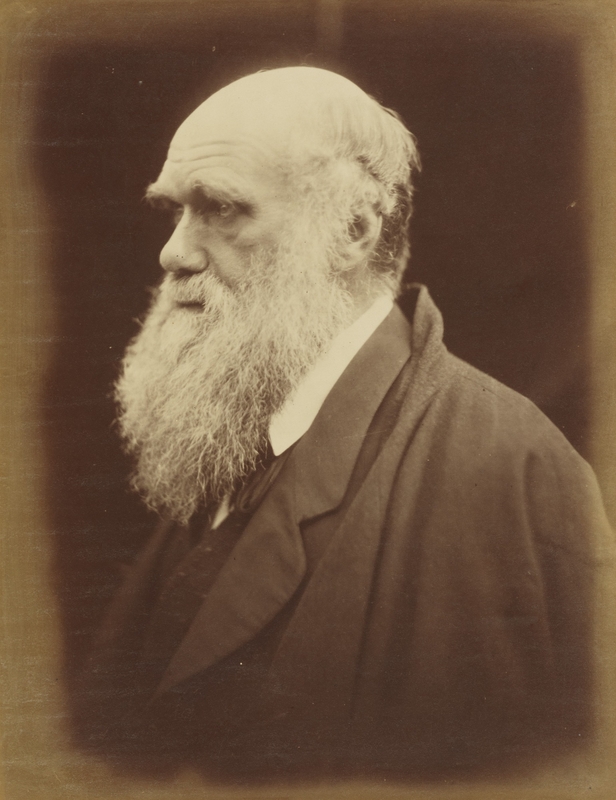

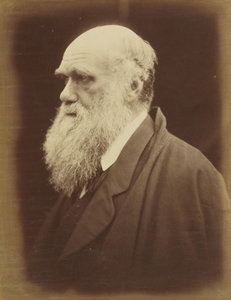

Up until the discovery of the ichthyosaur, it was widely believed that animals did not become extinct. Her findings even laid the groundwork for Charles Darwin's evolutionary theories in his On the Origins of Species (1859), which used Anning's work and fossils as irrefutable evidence that many species in the past looked nothing like species in the present.

The acclaimed palaeontologist William Buckland also used Anning's discoveries on bezoar stones in 1829 to propose that fossilised faeces, often found in the abdominal region of ichthyosaur skeletons, should be called 'coprolites'.

Anning's close and lifelong friendship with Henry de la Beche (1796–1855) in Lyme Regis led him to study geology. He spent many years learning from her, eventually becoming Director of the Geological Survey of Great Britain and President of the Palaeontographical Society.

In 1830, he drew a sketch and watercolour Duria Antiquior – A More Ancient Dorset which captured prehistoric life based on Anning's evidence found in Jurassic limestone along the Lyme Regis coast. It is credited with being the first visualisation of 'deep time' based on fossil evidence.

Duria Antiquior – A More Ancient Dorset

1830, watercolour by Henry De la Beche (1796–1855)

De la Beche created the work and organised its sale to support Anning financially when she came upon hard times in the 1830s. This painting is an enlargement by Robert B. Farren of a pencil drawing by De la Beche, who presented his drawing to Buckland to be printed for the meeting of the British Association in 1832.

Life in the Jurassic Sea 'Duria Antiquior' (An Earlier Dorset)

c.1850

Robert B. Farren (1832–1912)

Throughout her life, Anning continued searching for fossils and trading them at her fossil shop which she bought in Lyme Regis at the age of 27 in 1826. Known as 'Anning's Fossil Depot', her business was reported on in local papers and visited by many renowned geologists and fossil collectors across Europe.

Among the fossils, rocks and curiosities, the shop contained dozens of beautiful ammonites – shell-like Jurassic fossils – which inspired the name of Lee's film. Over the course of her career, she also found fossils of cephalopoda, plesiosaurs, dimorphodon, and various species of fish.

The work was often dangerous, and in 1833, she even lost her dog in a landslide. She wrote the following to Charlotte Murchison, in November of that year:

'Perhaps you will laugh when I say that the death of my old faithful dog has quite upset me, the cliff that fell upon him and killed him in a moment before my eyes, and close to my feet... it was but a moment between me and the same fate.'

In 1865, nearly two decades after her death, Charles Dickens' periodical sang her praises in an uncredited article titled 'Mary Anning, the Fossil Finder', which proclaimed: 'her history shows what humble people may do, if they have just purpose and courage enough, towards promoting the cause of science... the carpenter's daughter has won a name for herself, and has deserved to win it.'

To learn more about the life and key discoveries of Mary Anning, you can visit the Lyme Regis Museum in Dorset.

The Natural History Museum in London also holds some of her discoveries. Francis Lee's film Ammonite is in UK cinemas from 11th September 2020.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

Further reading

Tracey Chevalier, Remarkable Creatures: A Novel, HarperCollins, 2009

Charles Dickens, 'Mary Anning, the fossil finder', All The Year Round, 1865

Thomas W. Goodhue, Fossil Hunter: The Life and Times of Mary Anning (1799–1847), Academica Press, 2004

Martina Kölbl-Ebert, 'Charlotte Murchison (Née Hugonin) 1788–1869', Earth Sciences History, 16 (1), pp. 39–43, 1997