In William Orpen's portrait of a Bloomsbury family, the dominant figure of the father sits in the foreground, in profile, fingers laced, in a polka dot coat, ruminating with a severe expression.

While his youngest child poses primly in front of him, there are hints of dissent in the sidelong glances of the older children at the dinner table. And at the back, by the door, the strangest, orphan-like figure of his wife, shrunken in scale and gazing out with a forlorn expression.

The portrait is centred on Orpen's friend, the distinguished painter William Nicholson. He was a patriarch of a family described as one of the greatest dynasties of British art. Shown are Ben Nicholson, the oldest child, who becomes a towering figure of British abstract art, and forms a famous partnership with Barbara Hepworth. Anthony, a soldier who died in the First World War. Annie 'Nancy' Nicholson, the fabric designer and feminist who married the poet Robert Graves in 1918. Kit, the youngest, a future modern architect.

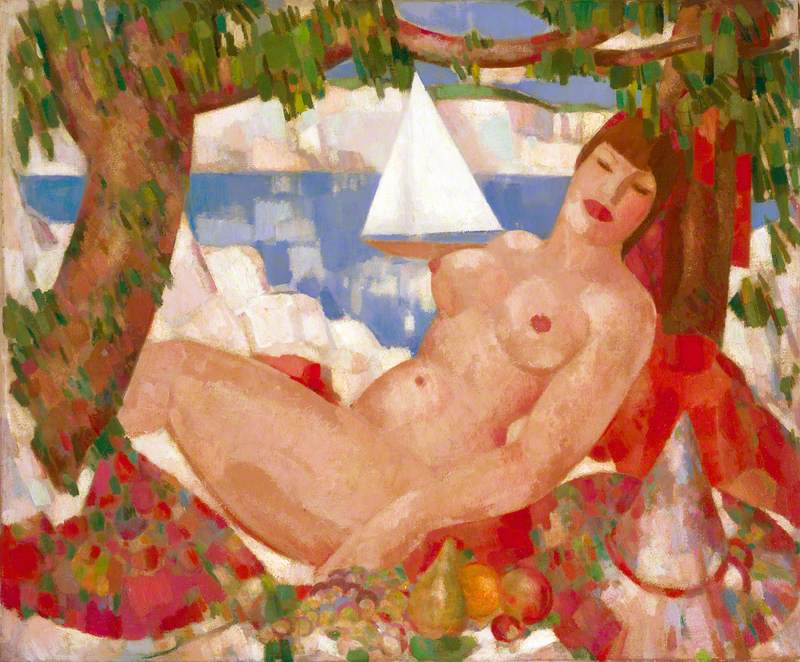

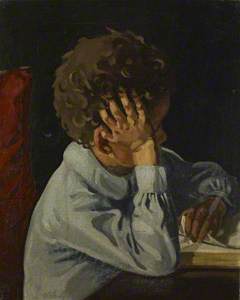

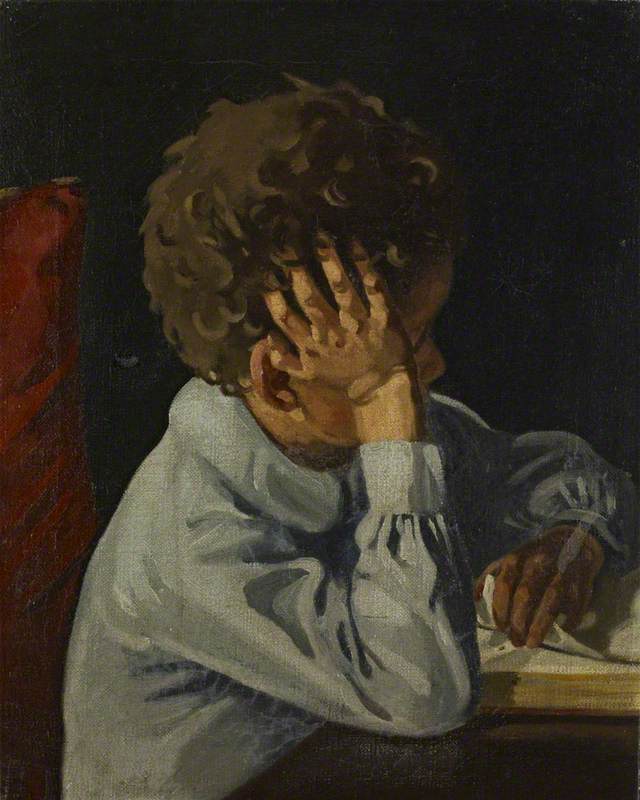

The Red Jersey

(Christopher 'Kit' Nicholson, 1904–1948, the artist's son) c.1912

Mabel Nicholson (1871–1918)

Often overlooked, until the recent focus on redressing the balance for women artists in British art history, is the figure of Nicholson's wife, Mabel Pryde Nicholson, sister of the artist James Ferrier Pryde. Her professional career was short – from 1904 to 1917 – but she remains a considerable painter in her own right.

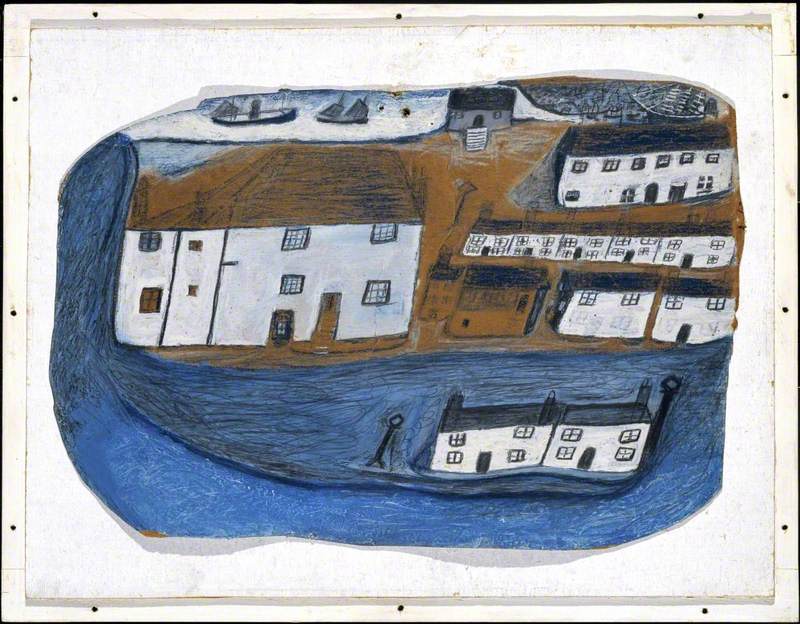

Mabel Nicholson's oil painting The Grange, Rottingdean appeared in the milestone show focused on female painters and sculptors, 'Modern Scottish Women, Painters and Sculptors 1885–1965', on loan from a private collection.

Excited to welcome Scottish artist Mabel Pryde's 1911 work 'The Grange, Rottingdean' back on display at #ScotModern

— National Galleries of Scotland (@NatGalleriesSco) March 3, 2020

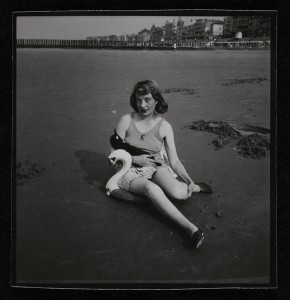

The subjects are Nancy and Kit, two of Pryde's four children. The artist frequently painted her children and insisted on paying them a small fee to model pic.twitter.com/NbM9fk5moC

Ten of Nicholson's works feature on Art UK, including her telling portrait of the young Ben Nicholson, showing a marked resemblance to his mother's expression in the Orpen painting, in the National Portrait Gallery collection.

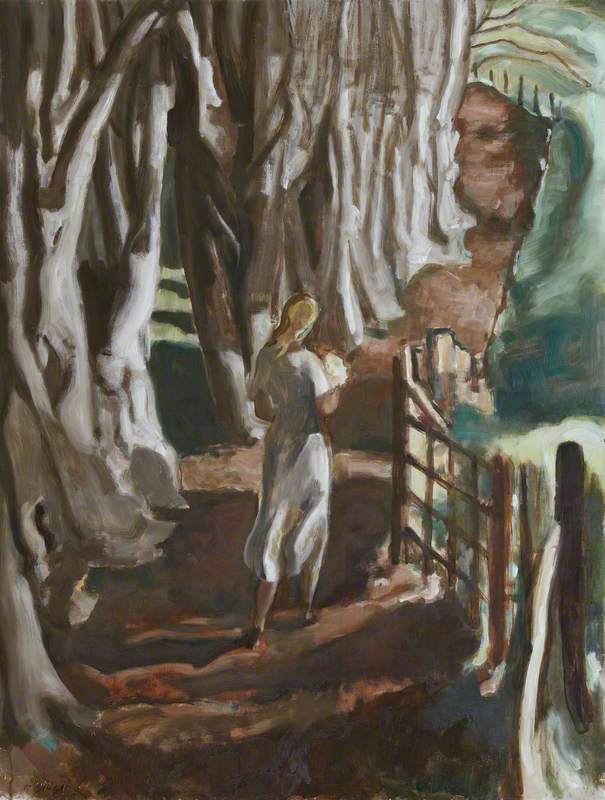

Most of her works use her own children as her models in striking, characterful poses, sometimes in theatrical costumes; the family were avid theatre-goers who kept a costume box, and the figure of Harlequin was a favourite subject.

The most famous story of Mabel Pryde is told of this rebellious young woman driving a flock of geese into the life class at Hubert von Herkomer's art school in Bushey, Hertfordshire, run by the then-famous portraitist. She had persuaded her father to send her at the age of 17, and it was there she first met the young William Nicholson.

One writer spoke of her 'strong sense of the ridiculous' and freely described the young art student as 'a strapping hoyden, with no reverence for art whatever, more talent than all the rest put together, and incorrigible laziness.' William, her shocked parents had learned, was not her first lover at the school, despite its segregated classes.

Pryde was the youngest of seven children, daughter of Dr David Pryde, Chairman of the Edinburgh Pen and Pencil Club and headmaster of Edinburgh Ladies' College. Her father insisted that the failure to educate girls was 'one of the great calamities of the human race'; her mother was said to be a domestic despot. In a wild family, she was described careering along the garden walls of Edinburgh on stilts. Reflected, perhaps, in the sturdy faces looking out of her paintings.

Nicholson quit Herkomer's school and made an artist's foray to Paris, but they married on his return to London in 1893, without her parents' knowledge.

While Mabel Nicholson has two works in the Tate, and the National Galleries of Scotland, she does not appear in overviews like Duncan Macmillan's Scottish Art in the 20th Century (Mainstream, 1994).

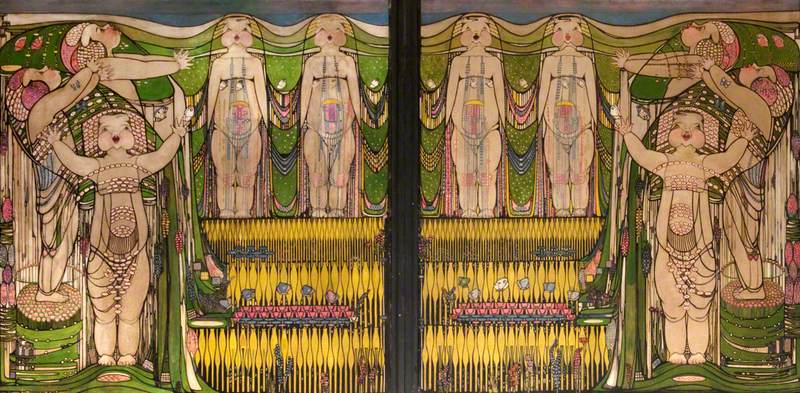

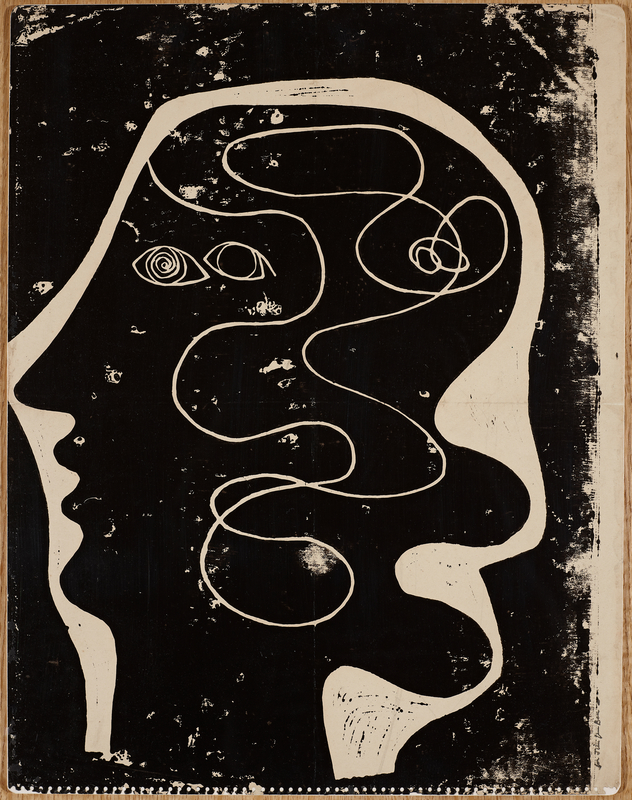

After meeting Mabel at Herkomer's, William Nicholson became a close friend of her brother, the artist James Pryde. The architectural fantasies that figure in James Pryde's later paintings include favourites like The Unknown Corner in The Fleming Collection. James grew up with Mabel in a house in Fettes Row, and had trained in Edinburgh and Paris and tried a career as an actor. With William Nicholson, under the pseudonym 'J. & W. Beggarstaff', he was responsible for some remarkable pieces of graphic design in the 1890s.

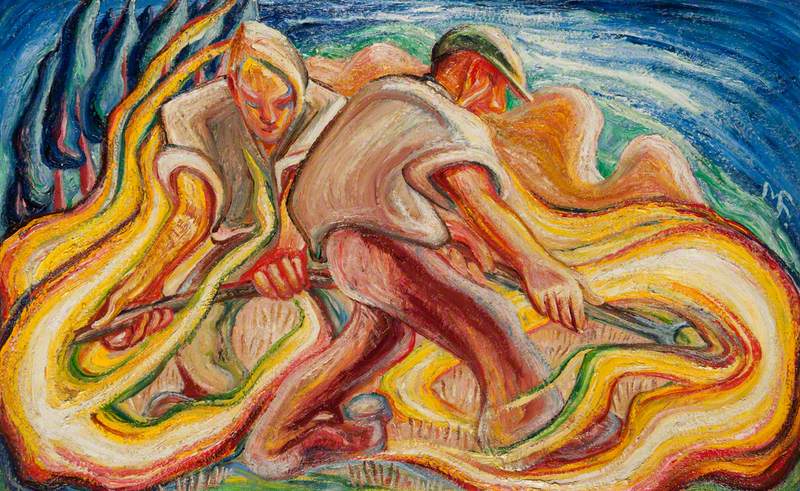

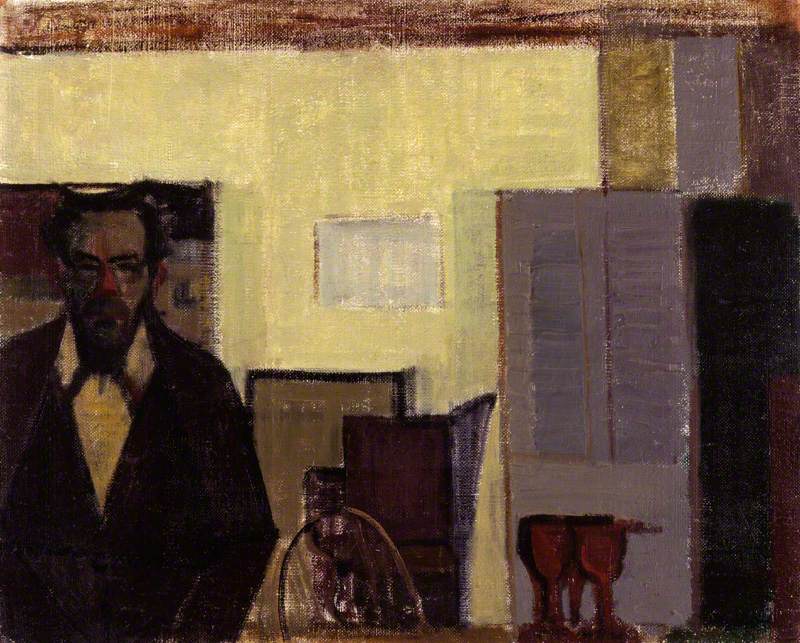

Sir William Nicholson made his career as a portraitist but who is now chiefly admired for his still lifes. It is said that these were an early influence on his son Ben's work. But Ben Nicholson described his mother as 'the rock on which my whole existence has been based.' While William Nicholson's mistresses notably included their housekeeper, Marie Laquelle, Mabel Nicholson bonded closely with her children; in 1913 she travelled to Madeira with Ben for his health after he suffered a severe asthma attack.

The space for Mabel as an artist was bordered first by the ambitions of her father and later by her husband's career and the needs of her children. But she was also an emancipated woman of the Suffragette age, and from 1910 to 1916 she showed at the Goupil Gallery and in other exhibitions, with her only solo show at the Chenil Gallery in London in 1912. Her subjects moved from single figures to figure groups to animals.

She died in 1918 in the influenza epidemic, aged 47; her son Tony died of wounds in the trenches a few months later. Ben and Nancy organised a memorial exhibition of 28 of her works.

The Tate carries Ben's list of photographs of her surviving paintings in its Ben Nicholson archive. It includes Family Group, and The Harlequin, both now in the Tate's collection. When Ben Nicholson won the Order of Merit in 1968, he complained angrily to Debrett's Peerage about his entry after it failed to mention his beloved mother.

With William Nicholson, Mabel had lived in the midst of artistic Bloomsbury society. His subjects included J. M. Barrie, for whom he produced the first sets for the play of Peter Pan, and Max Beerbohm. Beerbohm described 'Prydie', as Mabel was known, as 'looking like the result of an intrigue between Milton and the Mona Lisa.'

The National Galleries of Scotland hold William Nicholson's pencil and watercolour portrait of Mabel, dated 1897. She is concentrating fiercely on reading the book or newspaper held in her hand, in a large handsome hat with splashes of blue. She was described in later life as an often reclusive figure, from a time when female artists were still expected to abandon their work after they married.

But Ben Nicholson would also recall from childhood her disdain for pretention: 'After a lot of art-talk from our visitors my mother always said that it made her want to go downstairs and scrub the kitchen table... I always remember my mother's attitude when I came to carve my reliefs.'

Tim Cornwell, freelance arts writer

.jpg)