Lynette Yiadom-Boakye's work often yields a sense of intrigue. Her paintings, which frequently feature Black men and women, have been politicised because of her use of predominantly Black figures, leaving many viewers to dissect the potential socio-political nature behind her work.

In a 2012 interview with curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, Yiadom-Boakye addressed this. 'People are tempted to politicise the fact that I paint Black figures, and the complexity of this is an essential part of the work', she said. 'But my starting point is always the language of painting itself and how that relates to the subject matter.'

Yiadom-Boakye was born in 1977 in London and is of Ghanaian heritage. Her parents emigrated from Ghana to the UK where they worked as nurses for the NHS. She studied at Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design and later attended Falmouth College of Arts where she graduated in 2000 and completed an MA degree at the Royal Academy Schools in 2003. Following her graduation, Yiadom-Boakye held down various jobs – including one testing mobiles in a phone-recycling plant, according to The Guardian.

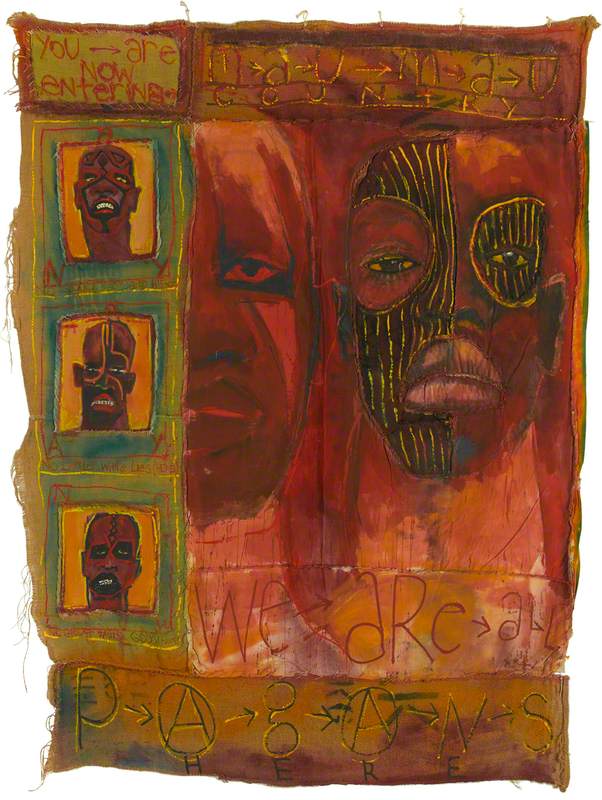

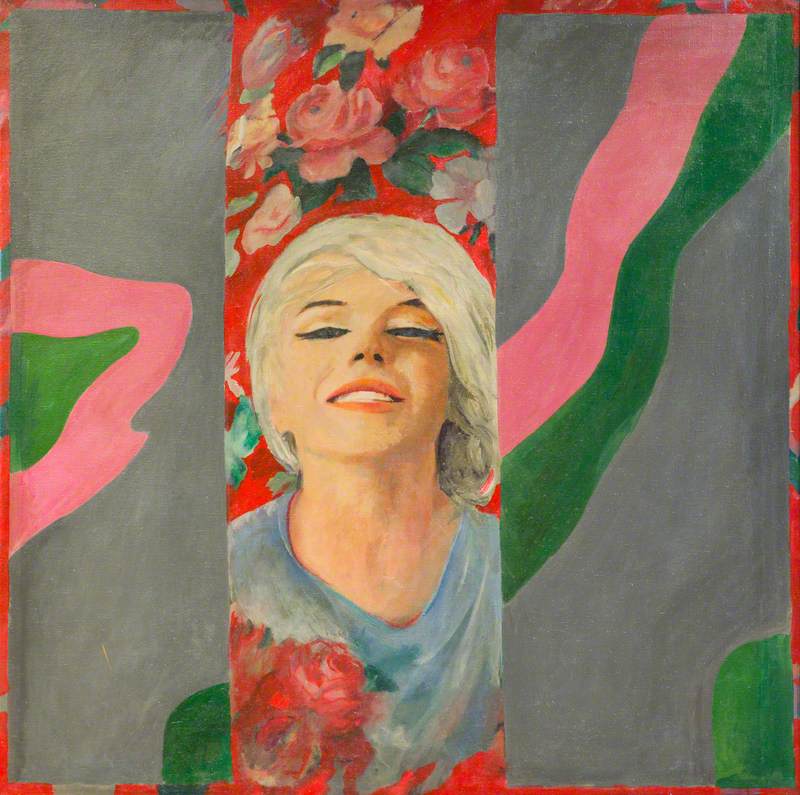

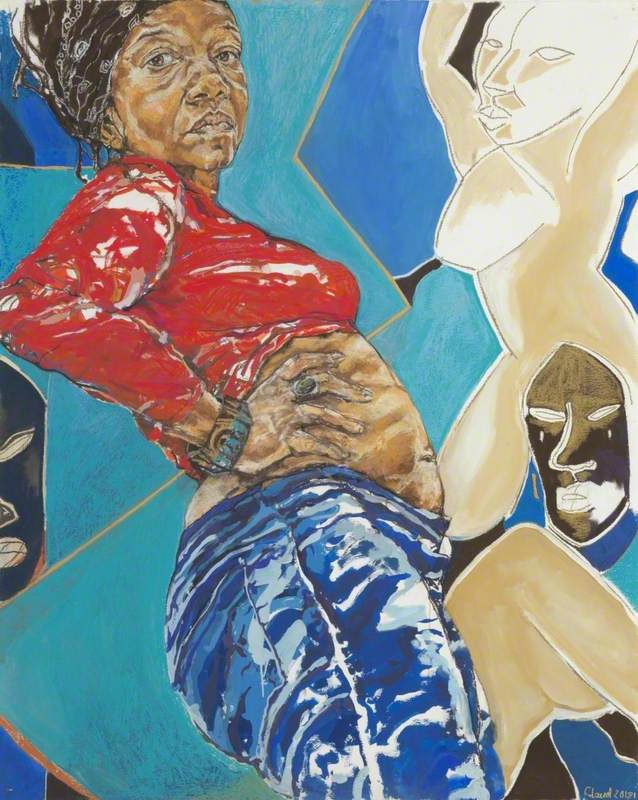

During this time, Yiadom-Boakye adopted a cartoonish style of painting as seen in Condominium (2005). Speaking about this painting in 2005, she said: 'I was thinking about the powerful, the able, the politically active, those who believe in camaraderie and their dependents. The reclining pose is more appropriate with smart and tight-fitting clothes.'

With the sitter staring directly at the viewer, Condominium presents a portrait which is both intriguing and humorous – something which the painter has discussed as her style, evolved over the years.

In a 2017 interview with The New Yorker, Yiadom-Boakye said of this earlier style: 'It must have been a reaction to a lot of what was said to me. Humour and horror made sense because that was how I felt. Often times it really worked, other times it was hugely dissatisfying. I think that's why I got rid of so much of it as I went along.'

'Over time I realised I needed to think less about the subject and more about the painting. So I began to think very seriously about colour, light, and composition. The more I worked, the more I came to realise that the power was in the painting itself. My 'colour politics' took on a whole new meaning.'

It wasn't until 2006 that Yiadom-Boakye was able to work full-time as an artist, following her success in winning The Arts Foundation Fellowship for Painting that same year.

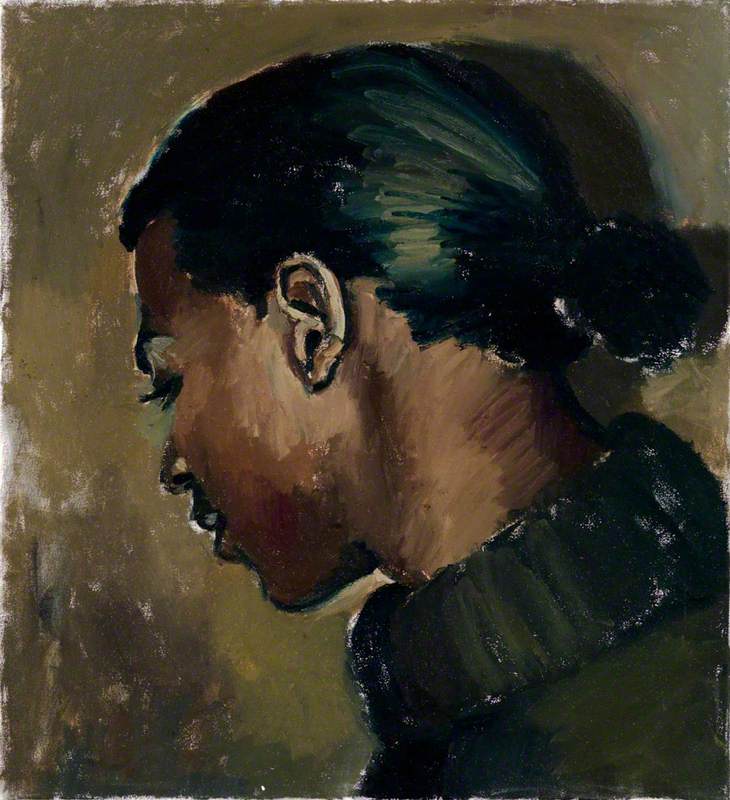

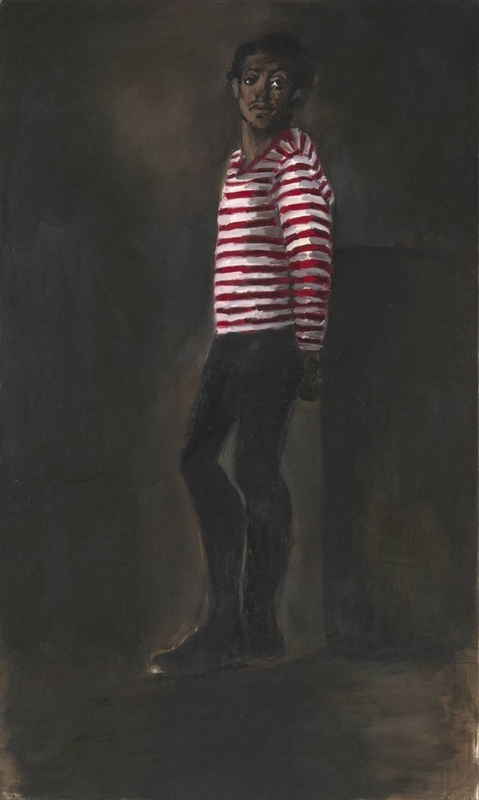

Her figurative oil paintings continued to evolve, but many signatures remained the same. The artist became synonymous with her use of raw, muted colours, incorporating an array of blacks and browns, and the fictional figures which featured in many of her works.

While many of her portraits contain a single sitter, Yiadom-Boakye has also created paintings of multiple Black figures, as seen in The Generosity (2010), Condor and the Mole (2011) and Complication (2013).

Complication

2013, oil on canvas by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (b.1977), private collection

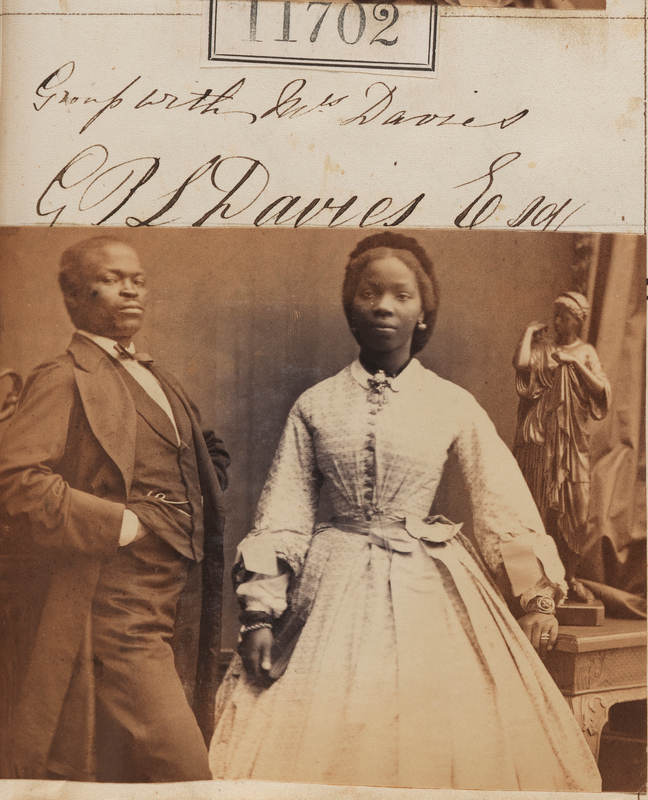

The latter paintings along with others by Yiadom-Boakye, have been celebrated for their portrayal of Black normalcy, where Black men, women and children are depicted in domestic settings as opposed to places of struggle and trauma.

This very visible Black normativity is rarely seen in Western European or American portraiture, leading some to suggest her work is a critique of Western art's relationship with Blackness. However, Yiadom-Boakye has frequently noted that her use of Black figures is merely drawing from her own inspiration rather than a source of conscious critique.

Everything is up for interpretation, however. Yiadom-Boakye describes her work as 'ahistorical', with little reference to particular time periods through the use of 'timeless' clothes, muted colour palettes, and an absence of references to her subjects' social class.

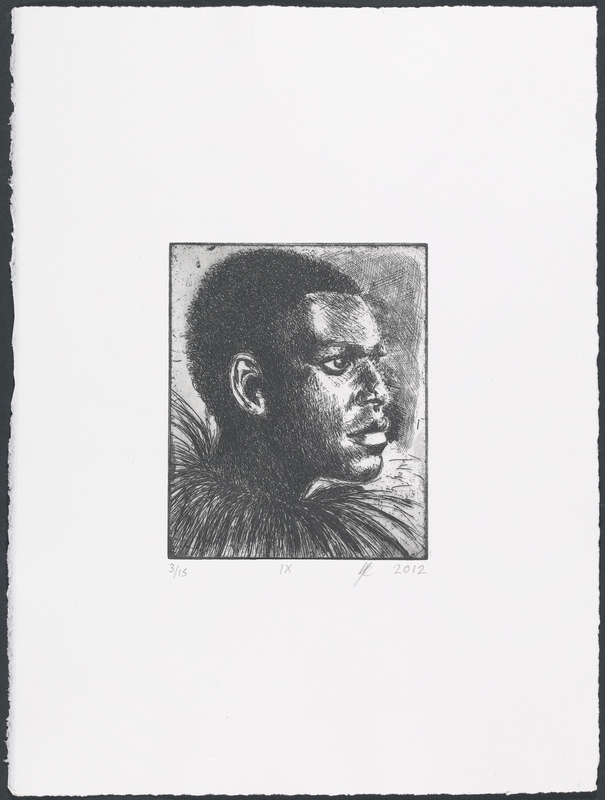

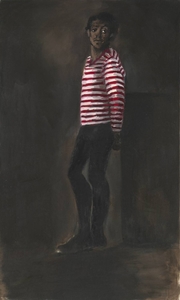

This can be perfectly seen in 10pm Saturday (2012) – a portrait of a Black man standing alone with nothing else in sight. The dark colour palette evokes a stillness as the viewer is compelled to focus on this ahistorical fictitious character. This is one of the many examples of Yiadom-Boakye's captivating work which challenges the viewer to be at their most creative and generate their own narrative.

In 2012, Yiadom-Boakye became the recipient of the Pinchuk Foundation Future Generation Prize. In a press release, the jury praised her 'extraordinary paintings where darkness and light are articulated together, recognising the quality of the paintings and the social concerns that emerge from them.' The accolades continued as she was shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 2013, for her exhibition 'Extracts and Verses' at Chisenhale Gallery.

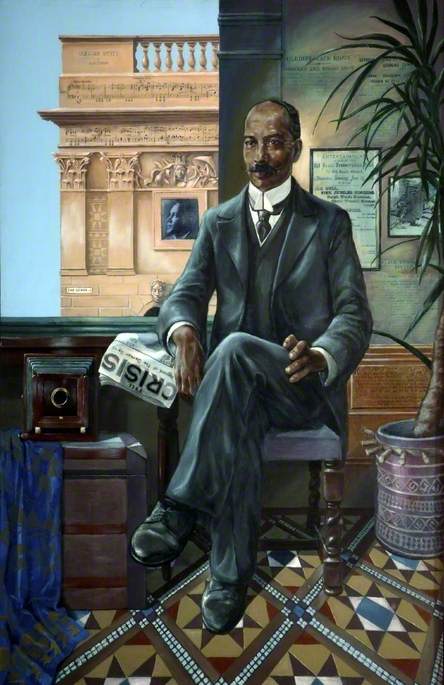

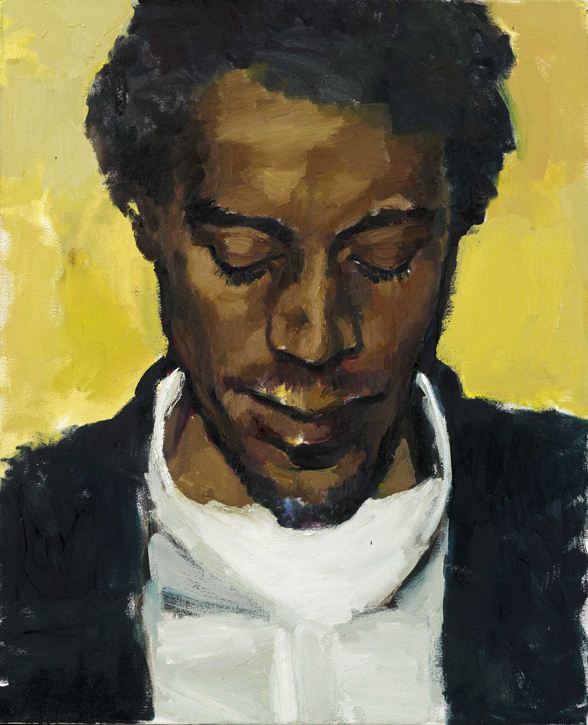

Tie the Temptress to the Trojan

2018, oil on canvas by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (b.1977), collection of Michael Bertrand, Toronto

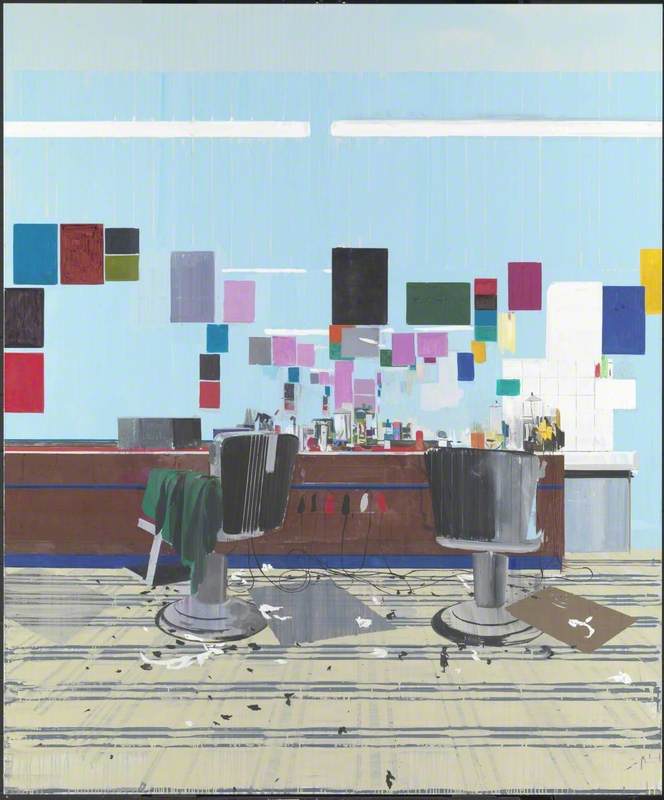

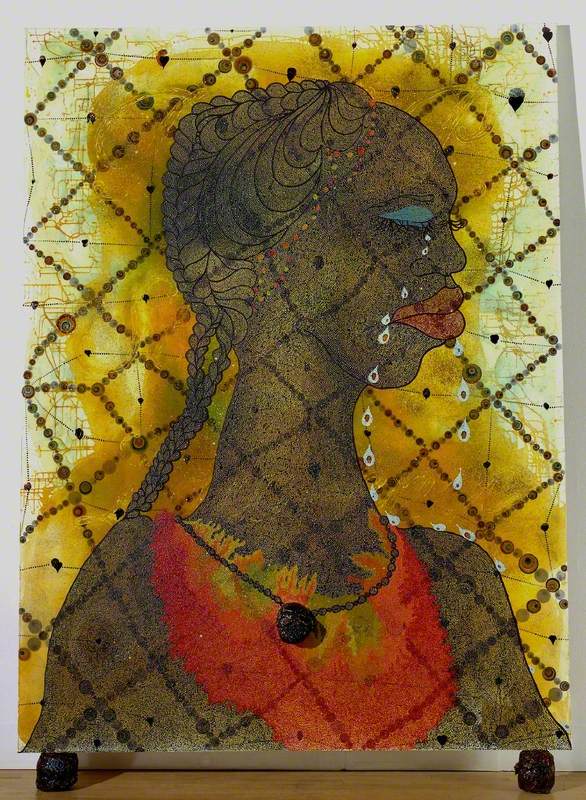

As the years went on, Yiadom-Boakye's paintings entered a new phase as her relationship with colour shifted, as demonstrated in her show 'In Lieu of a Louder Love' at Jack Shainman Gallery.

The paintings in the show featured a brighter, warmer colour scheme which was a departure from the dark palette which many had become familiar with.

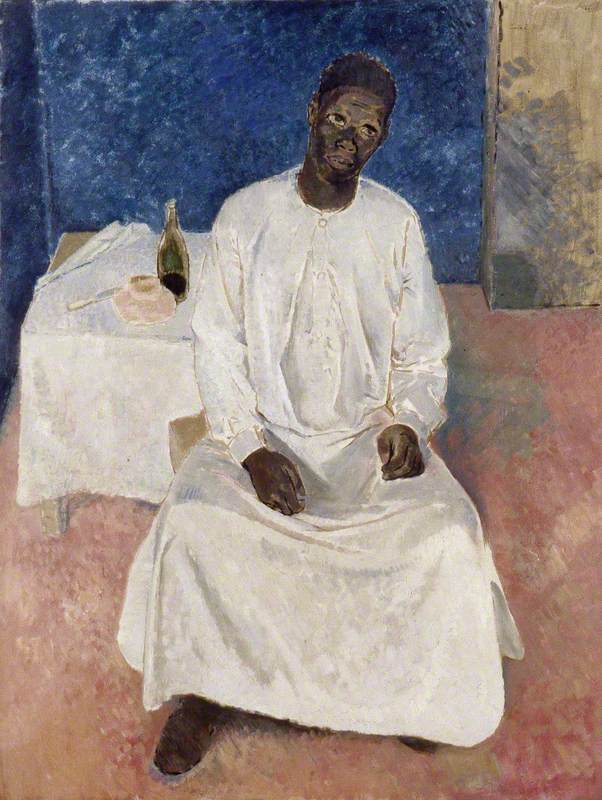

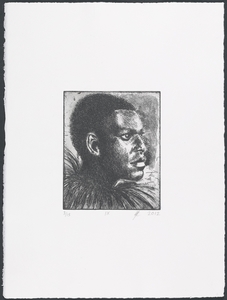

A Passion Like No Other

2012, oil on canvas by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (b.1977), collection of Lonti Ebers

In an interview with The Guardian, Yiadom-Boakye said: 'In the last few years, I've become obsessed with colour, too. My pictures used to be very dark, but now I'm putting in vivid reds and greens.'

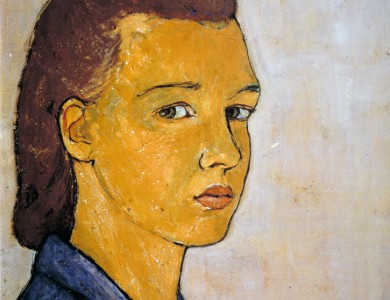

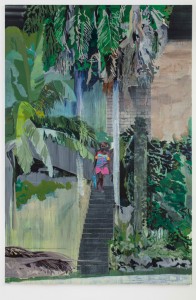

To Improvise a Mountain

2018, oil on canvas by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (b.1977)

This growth within Yiadom-Boakye's work continues to keep many onlookers fascinated as her fictional subjects, relationship with colour and more evolves.

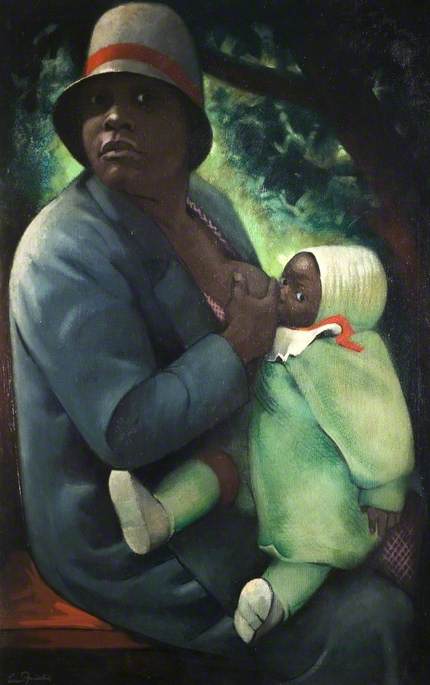

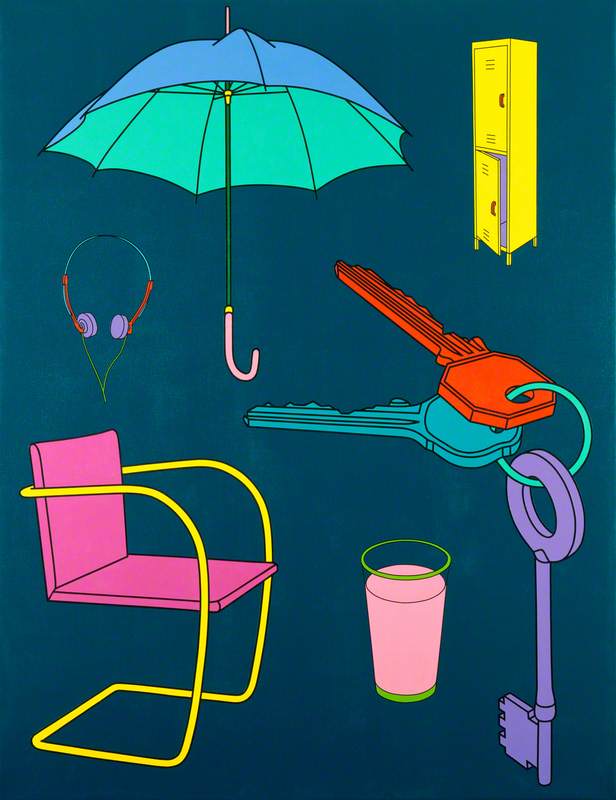

Citrine by the Ounce

2014, oil on canvas by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye (b.1977), private collection

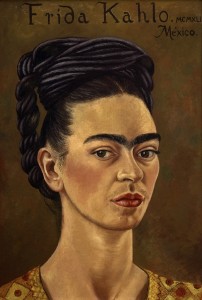

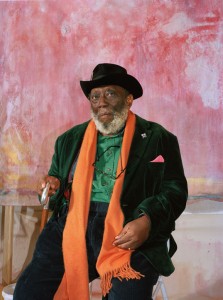

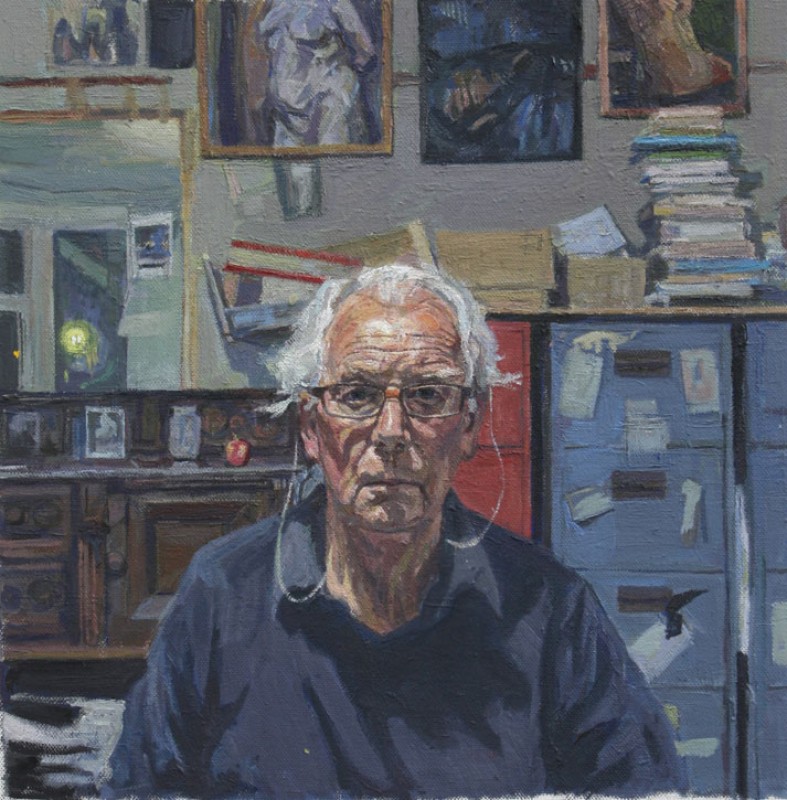

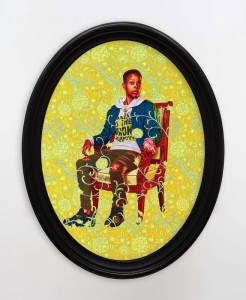

Her position within the British art scene was perfectly encapsulated in a 2017 portrait by artist Kehinde Wiley.

How does a recent painting of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye complement 18th-century British portraiture? Read #YCBA curator Matthew Hargraves's insight into our object of the week, painted by @kehindewileyart (#Yale MFA 2001).

— YaleBritishArt (@YaleBritishArt) April 4, 2020

More: https://t.co/MFNqiKfTtt pic.twitter.com/lZzT3RHF8W

The portrait, which plays on the trope of a rich, landowning, eighteenth-century white man, places Yiadom-Boakye front and centre as she makes direct eye contact with the viewer and illustrates an image of a Black woman in a position of power and influence.

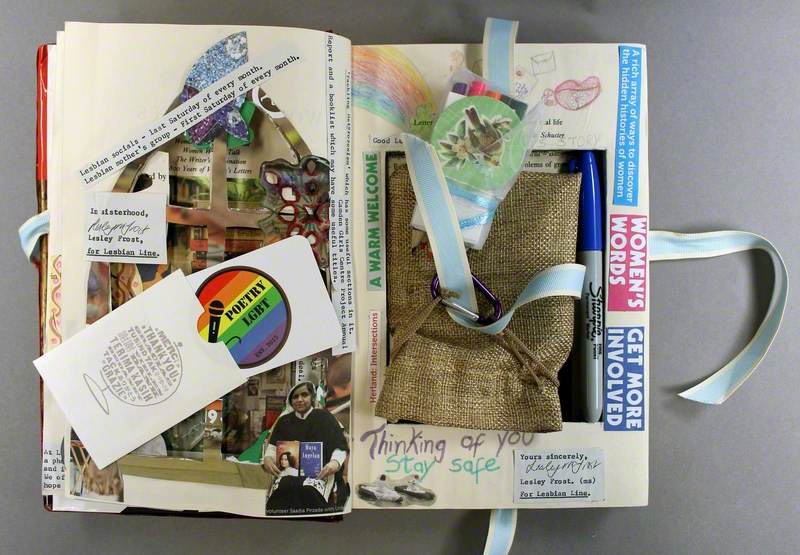

Her influence and work will be on full display at an upcoming Tate Britain exhibition, 'Lynette Yiadom-Boakye', which is currently closed to the public due to COVID-19.

Leah Sinclair, freelance journalist and editor