The first thing you see when you enter 'Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child' at The Hayward Gallery is a self-contained space concealed behind doors made of wood and frosted glass. A couple of panes are badly broken and printed on one door is the word 'Private'. Inside, flimsy white dresses and silk slips that had belonged to the artist and her mother are loosely suspended from cattle bones and metal armatures. They preside over a bronze model of Bourgeois' childhood home in Choisy-le-Roi, a town southeast of Paris.

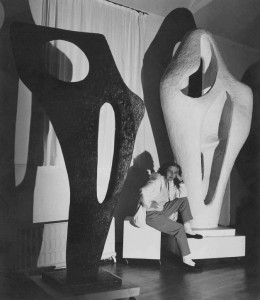

Installation view of 'Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child' at The Hayward Gallery, 2022

Light and dark are threaded throughout this spellbinding and sometimes scary exhibition, which focuses on the triumphant final two decades of Louise Bourgeois' long career, when she began to incorporate clothes and other textiles such as handkerchiefs, bed linen and needlepoint into her art. 'These garments have a history, they have touched my body, and they hold memories of people and places,' the French-born, New York-based artist, who died in 2010, once said. 'They are chapters from the story of my life.' The show brings together colossal installations, delicate collages, fabric and lithograph books, stuffed and sewn-together figures, and tall tapestry towers.

Installation view of 'Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child' at The Hayward Gallery, 2022

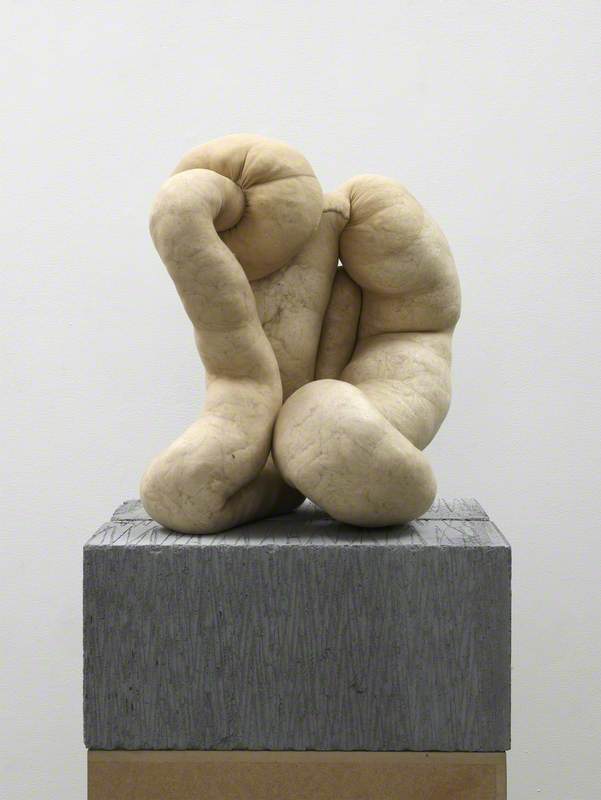

Bourgeois' aim with these works was to dramatise an emotion: stuffed fabric heads with open mouths and squeezed-shut eyes evoke a range of conflicted mental states, from hysteria to rejection. At times, she used art to try to understand a particular mood – for example, the withdrawal of her youngest son, Alain. The Reticent Child (2003) comprises little pink figurative sculptures in various life stages arranged in front of a curved mirror. With her stacked fabric blocks, she tried to contain chaotic feelings with some semblance of order and balance.

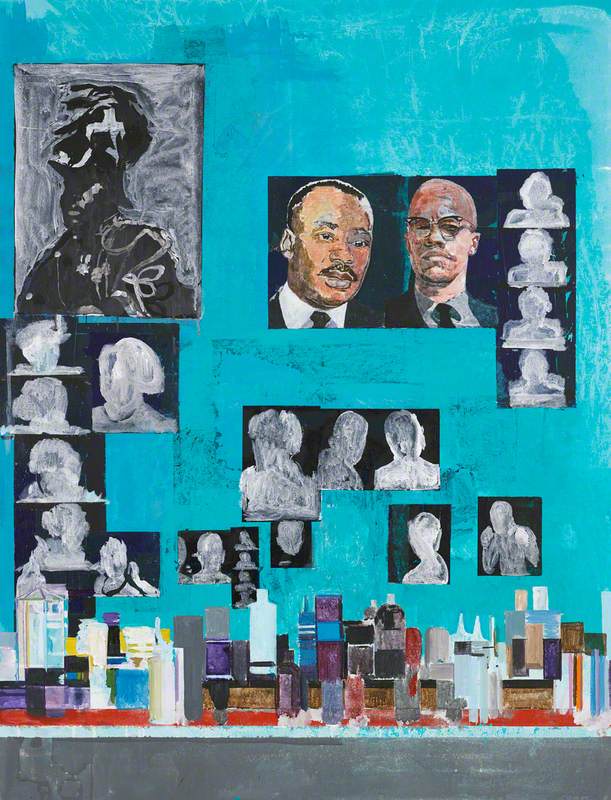

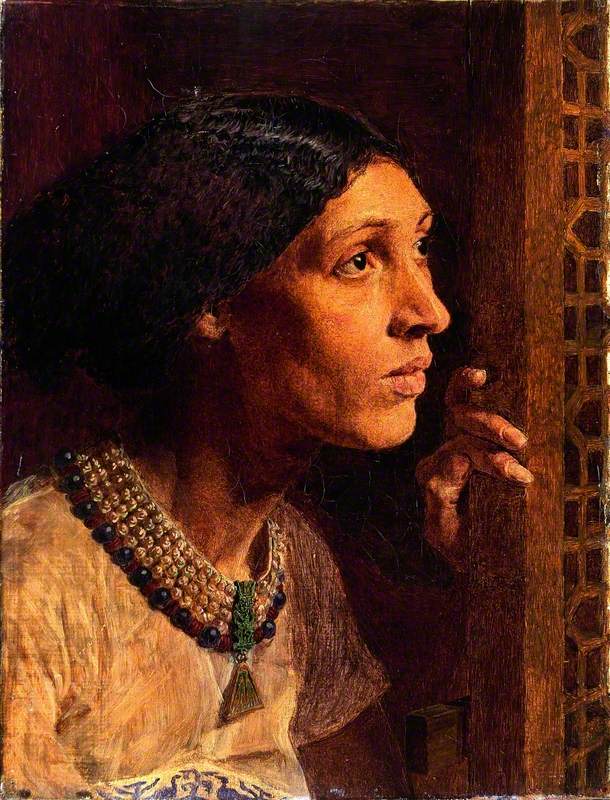

Detail of 'The Good Mother'

2003, sculpture by Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010)

Emotions in Bourgeois' art are heightened by her choice of textiles. The Good Mother (2003) shows a woman without arms kneeling in a submissive pose with milky-white threads tethered to her breasts. The soft, pink fabric of the female figure lends the work a certain intimacy, while the fine threads, lolling between her and five small bobbins, hint at the fragility of early motherhood. Displayed on a plinth encased within a glass vitrine, there's also the sense that others might be watching, or even judging.

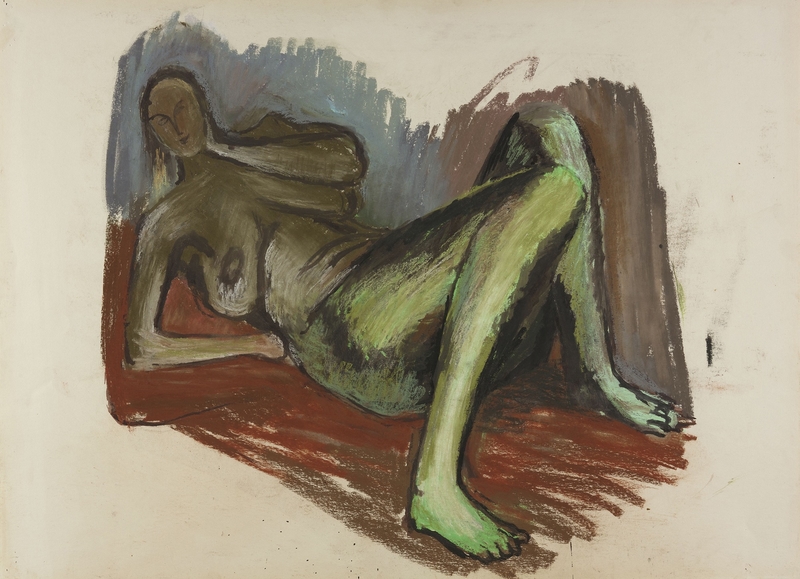

High Heels

1998, fabric & steel with wood & glass vitrine by Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010)

Many of these fabric works amplify the themes of identity, sex, trauma and death that Bourgeois explored in her earlier art. In High Heels (1998), another female figure without arms lies face down, her torso twisted to expose her heaving chest. The grey and black fragments of clothing that make up her body are soft to touch, while the spiked steel shoes attached to the end of her legs could be used as weapons. In Spiral Woman (2003), a dizzying life-sized figure is composed entirely of black cloth, consumed by anxiety, alienated.

Installation view featuring 'Spiral Woman'

So far, so harrowing, but Bourgeois – and the curators at The Hayward Gallery – know when to ease off. After stumbling across a headless fabric figure hanging by its feet above the stairs, you come to The Fragile (2007), a series of digital prints and screen prints on cloth showing childlike depictions of spindly-legged spiders and smiling pregnant women.

Installation view of 'Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child' at The Hayward Gallery, 2022

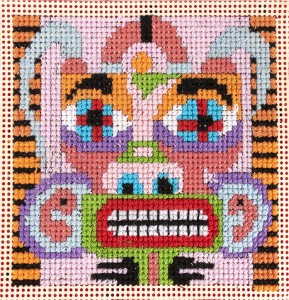

Another series of brightly coloured fabric collages whose compositions resemble skilfully spun spiders' webs could be viewed as purely decorative; a few flowers are caught in the webs of striped and patterned cloth.

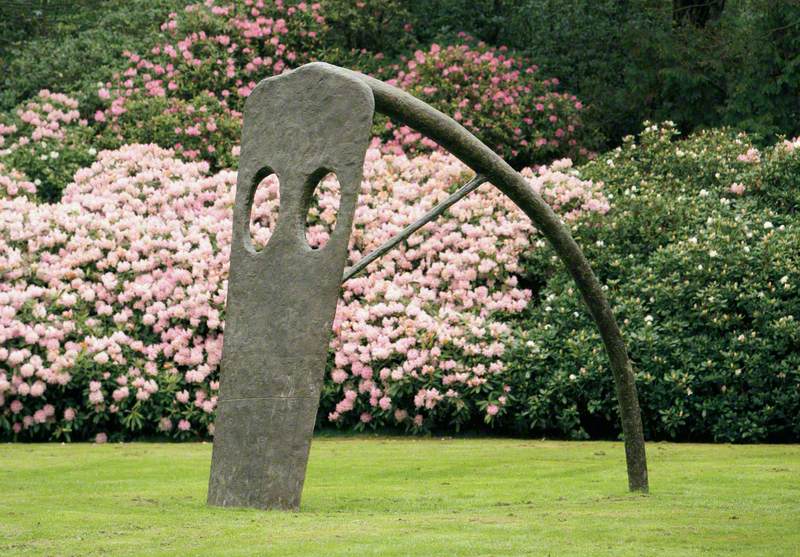

Bourgeois associated spiders with her mother, who was a weaver and an ancient tapestry restorer, and they appear at various points during the show. Spider captures the artist's mixed feelings towards being both a daughter and a mother. With its needle-like legs, the monstrous sculpture straddles a cylindrical steel-mesh enclosure that has been partially patched up with old, threadbare swatches of tapestry. Inside is an upholstered chair and some personal artefacts, including a bottle of Bourgeois' favourite perfume and a stopped watch. Hanging beneath the spider's abdomen are three glass eggs bundled in fabric. It's both menacing and nurturing, loving and controlling.

Installation view of 'Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child' at The Hayward Gallery, 2022

It makes sense that Bourgeois, the daughter of tapestry restorers, turned to textiles. As well as a lens through which to explore her past, these scraps of fabric inspired her to look at life from a new perspective. They can be torn and cut, sewn and stitched, mended and repaired – and so it seems can our minds and our bodies. 'I came from a family of repairers', Bourgeois once said. 'The spider is a repairer. If you bash into the web of a spider, she doesn't get mad. She weaves and repairs it.'

Chloë Ashby, freelance writer and author of Wet Paint (Orion Publishing Co., 2022)

'Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child' at The Hayward Gallery runs until 15th May 2022