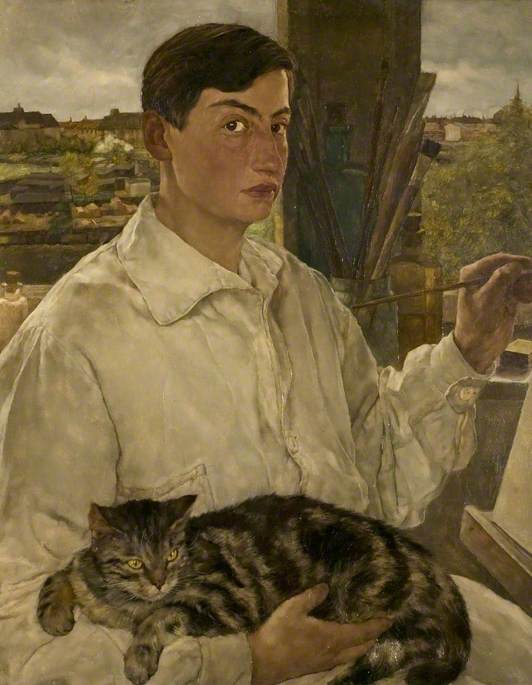

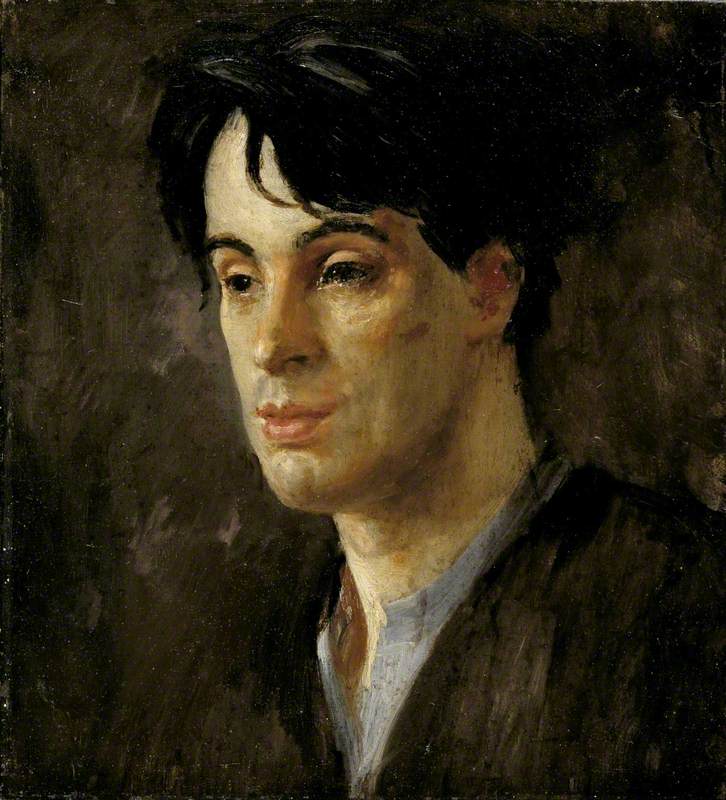

Lotte Laserstein's painting entitled Self Portrait with a Cat (1928) may be regarded as exposing a range of information about its creator, even for the casual observer. When creating this realist painting, the German-Swedish artist captured not only a detailed likeness of herself but carefully constructed the work to express much about her stance in life, in addition to her role as an artist.

The self-portrait was intended, of course, as a form of representation to project meaning on character, identity and status. For women particularly, creating images of themselves in the genre of painting has been a historically arduous task, as gendered assumptions and cultural limitations had to be ingeniously surmounted.

Yet, in her self-portrait Laserstein boldly confronts expectations. While both capturing and captivating the viewer with her direct gaze, her portrait was not a simple echo of the self but offered a challenge to perceptions of both 'the female artist' and womanhood itself. The work, in turn, was indicative of Laserstein's approach to the expression of her art and in her life more generally.

Born in Preussich-Holland in Prussia during 1898 into a family of part Jewish heritage, Laserstein lost her father at the age of just four years old. The death caused the family to relocate into the home of the artist's maternal grandmother. Here Laserstein's mother was known to paint ceramics and it can be presumed the young Lotte was influenced by such artistic endeavours.

Lotte Laserstein, Russian girl with powder box, 1928 #womensart pic.twitter.com/WEJpu83Yzo

— #WOMENSART (@womensart1) September 24, 2018

After the family moved again in later years to Berlin, Laserstein began her adult education in such areas as the history of art and philosophy, while also taking lessons in painting. Her entrance into the city's College of Fine Arts during 1921 was a bold move for the young artist in the first years of the school allowing entrance to female students. Her later completion of studies at the United State School of Liberal and Applied Art enabled Laserstein an excellent foundation for a career in art. The economic woes of the country in an era of high inflation, however, took a toll on the family's finances and the young artist was forced to work in such areas as industrial design.

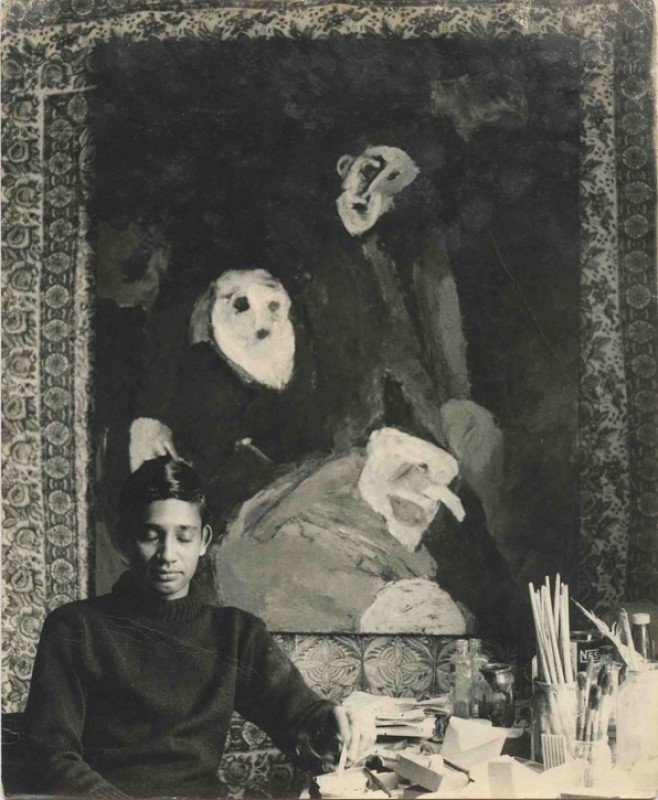

Nevertheless, Laserstein's promise in her chosen field of fine art was soon recognised by the school, who viewed her work as amongst the best at the academy and she was honoured by the Prussian Ministry of Science, Art and Education. Opening her own art studio in 1927 while supporting herself by giving painting lessons, the artist soon began creating her work in earnest. It was here, in the following year, that Laserstein created her self-portrait with the addition of her feline companion.

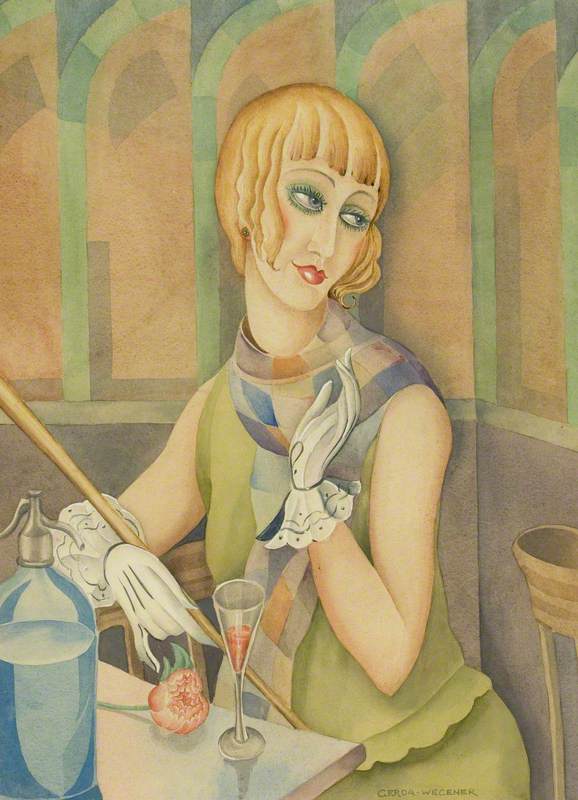

Traute Rose with white gloves, 1931 by Swedish-German painter Lotte Laserstein #womensart pic.twitter.com/Oic1djcMq5

— #WOMENSART (@womensart1) June 21, 2020

Laserstein began to be included in many exhibitions, and her work became more widely acknowledged as a result. Her prominent role within the Association of Berlin Women Artists further aided her career. The painter's art was centred on figurative reflections and portraiture in an age of post-expressionism, amidst the growing popularity of a movement known as New Objectivism. The artistic focus was being removed from the emotive outpourings of the previously favoured expressionist painters and had become fixed on an unsentimental realism.

The realistic work Laserstein produced during the late 1920s and early 1930s, often featuring her favoured female models, certainly caught the mood of the age. This era known as the Weimar Republic, encompassed a German renaissance in cultural terms despite the economic and political turmoil, as the Berlin bars bustled with artists and intellectuals within a flourishing bohemian scene.

Frau Im Café (Woman in a Café: Lotte Fischler)

1939

Lotte Laserstein (1898–1993)

Laserstein's portraits reflected not only the lives surrounding her but also the mood of the era. The painting Woman in a Café, a commission featuring the wife of a well-known lawyer, presents the subject as a fashionably attired woman of the age. The seated figure is featured alone with her cocktail, indicative of the growing independent spirit of women and is posed confidently as she leans forward to engage with the world she inhabits.

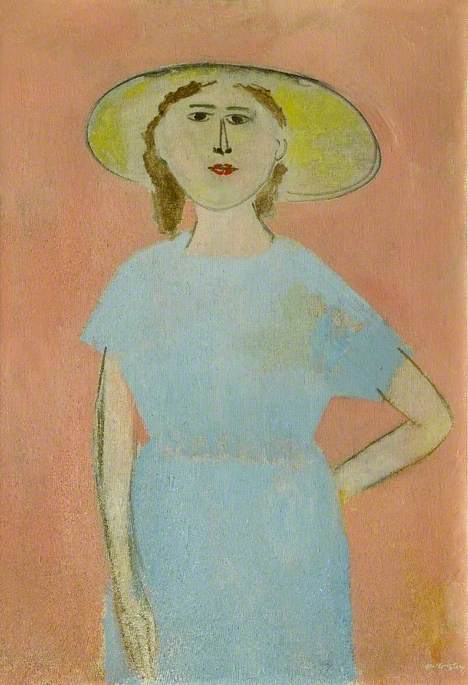

Another of Laserstein's paintings, The Yellow Parasol (1935), is reflective of a looser painting style for the artist and presents a young woman holding the object of the title. While a common theme in Western art since the nineteenth century, Laserstein added a twist to the familiar formula which avoids the contrived depictions of femininity common in the work of artists such as Renoir.

Here Laserstein presents her female subject as rather androgynously dressed, thus countering the cliches of the theme. This was an age of daring exploration after all, in which French artist Claude Cahun was toying with ideas of gender and German-born actress Marlene Dietrich was kissing women on screen dressed in a tuxedo. The model who posed for Laserstein's painting was known as Traute Rose, a close friend of the artist who featured in many of her artworks and played a significant role in the painter's life.

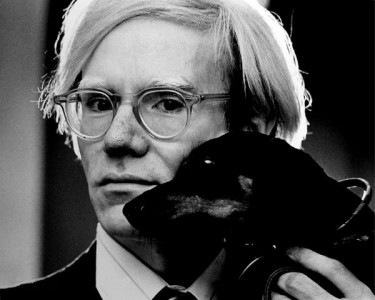

Claude Cahun (1894-1954), Jewish-French photographer, sculptor and writer known for her self-portraits in which she assumes a variety of personas often challenging ideas of gender #womensart pic.twitter.com/cRyIsOfwep

— #WOMENSART (@womensart1) March 24, 2018

Despite her increasing achievements with each new show and painting, Laserstein's artistic career was soon to be interrupted. The rise of Nazi anti-Semitism created a toxic atmosphere in which artists of Jewish heritage, like Laserstein, were excluded from exhibiting. Unable to purchase art materials easily and discharged from her role in art associations, the painter was forced to develop a plan of escape. In order to leave her homeland, emigrate to Sweden and gain citizenship, Laserstein married a Swedish man. However, she did not cohabit with her new husband and set up a new life independently in Stockholm.

Her efforts to save her mother, who remained in Germany, tragically failed and Meta Laserstein died at the hands of Hitler's regime in Ravensbrück concentration camp. The painter's loyal friend Traute, however, did manage to smuggle Laserstein's artworks out of Germany, avoiding their theft or destruction under Nazi rule. Living out her life in the Swedish capital, here Laserstein joined the Swedish Academy of Arts and continued to work particularly in the field of portraiture.

Lotte Laserstein, 'Madeleine' 1942 #womensart pic.twitter.com/A9NcygtuUs

— #WOMENSART (@womensart1) March 11, 2016

Understanding Laserstein's view of herself and her work is enabled by revisiting her Self Portrait with a Cat to decipher the codes instilled within oil on canvas. The significance of the setting is particularly relevant. The artist's studio, communicated by the centrality of the painter's tools in the background, connects the figure to her work and creativity. Meanwhile, the easel, canvas and hovering paintbrush in hand all highlight the act of painting as Laserstein flaunts her professional abilities to the viewer. The subject is reflected in suitable attire for the job, reflective of a practical approach to her work which purposely ignores gendered conventions on female appearance. In addition, the subject's hair is short, and she wears no make-up, or indeed, any sign of expected feminine costume. While enjoying the soft textures of the cotton overall and feline fur, the painter presents herself as particularly rigid and her gaze is strong, while her slightly raised eyebrow seems to question the viewer's assumptions.

Undoubtedly painted while looking into a mirror, the painter conveys an assured self-reflection buoyed by her burgeoning success. Also, by utilising a pose reminiscent of the self-aggrandising statements of male painters throughout history, Laserstein makes a carefully considered declaration of her own.

As is the case for so many women in the arts, Laserstein's work generally went into relative post-war obscurity and was only rediscovered in the last years of her life. An exhibition of her work was held in the late 1980s which showcased many of her paintings to a new generation. This included work featuring her notable male subjects also, such as Nobel Prize-winning biochemist Sir Ernst Chain in a 1945 portrait conveyed in Laserstein's typical realist style. The exhibition was attended by both the artist and her ever-present muse Traute, who appeared in many intimate artworks by the artist.

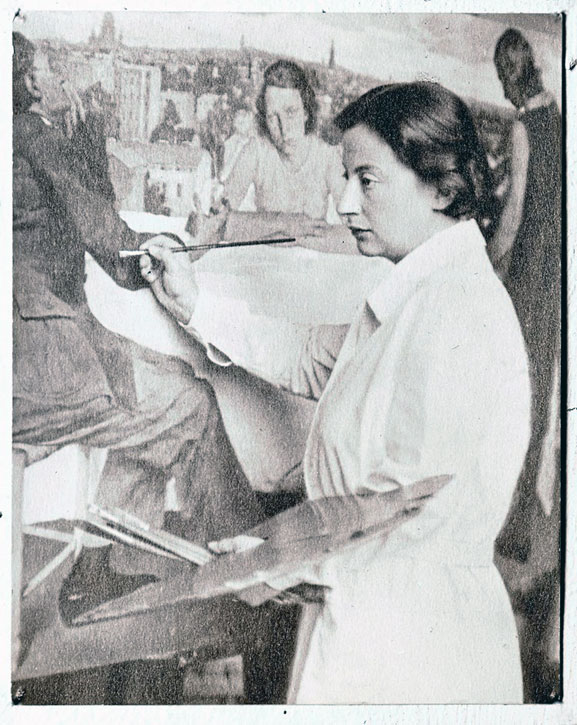

Lotte Laserstein painting her large work 'Evening over Potsdam'

1930, photograph by Wanda von Debschitz-Kunowski (1870–1935)

Laserstein died in 1993 as her paintings were finally receiving the international recognition they deserved. Her legacy, in turn, is one of presenting the world with a beguiling body of work which encompasses an obvious understanding of her subjects, perhaps no more so than in the portrait with a fearless female gaze.

P. L. Henderson, art historian and founder of @WOMENSART