The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge was founded by a shadowy Irish nobleman, Richard, 7th Viscount Fitzwilliam of Merrion. On his death, on the 5th February 1816 at his apartment at 31, Old Bond Street, Lord Fitzwilliam left the University of Cambridge his library of rare books, his collections of illuminated manuscripts and musical scores, over 40,000 prints, and 144 paintings – mainly Old Masters but with a few family portraits and other curiosities. He also bequeathed his alma mater £100,000 in South Sea Annuities, the income from which was to ‘cause to be erected and built a good substantial and convenient Museum, Repository, or other Building’.

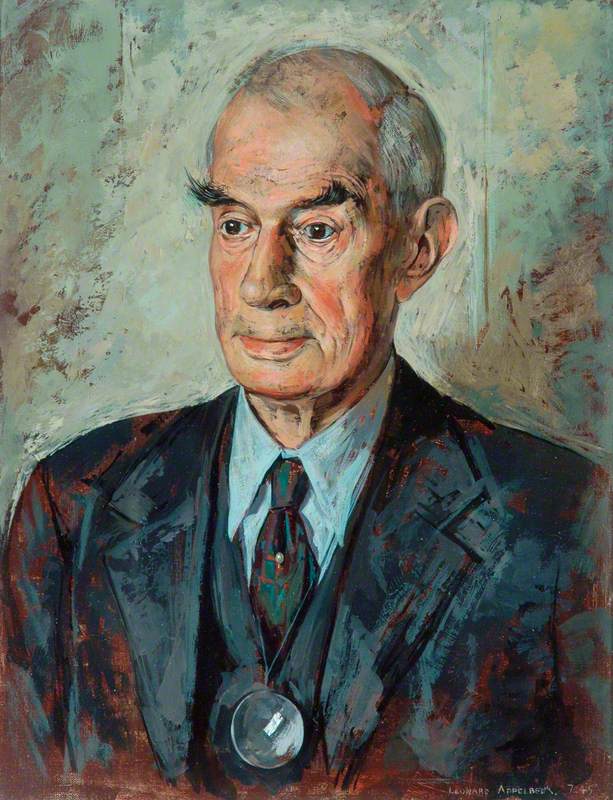

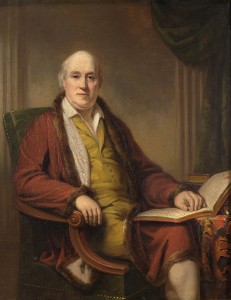

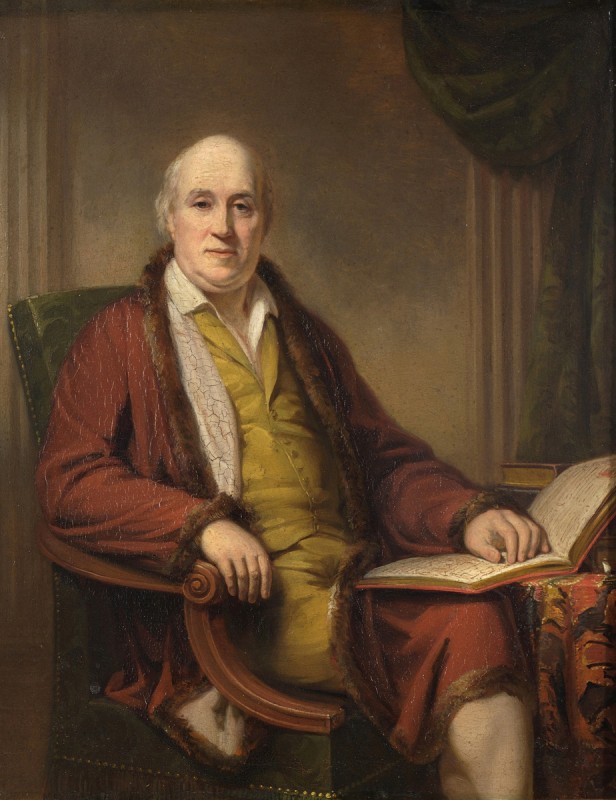

Richard, Seventh Viscount Fitzwilliam of Merrion

Henry Howard (1769–1847) (copy after)

Lord Fitzwilliam had divided his time between a house on Richmond Green and lodgings in Paris, where he maintained a long relationship with Mlle Zacharie, a dancer at the Opéra. While living in Paris, Fitzwilliam must have known the celebrated collection of Old Master pictures formed by successive ducs d’Orléans at the Palais Royale. In 1792, at the outbreak of the French Revolution, the then duc d’ Orléans, Philippe Egalité, sent the pictures to be sold in London. Egalité perished on the scaffold in 1793, and the pictures were mostly acquired by a syndicate composed of the 2nd Duke of Bridgewater, his nephew Earl Gower (later the 1st Duke of Sutherland), and the Earl of Carlisle.

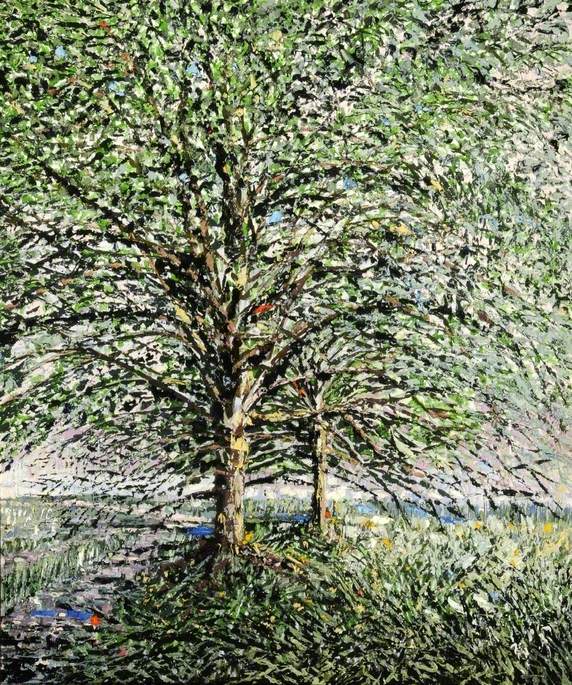

Pineapple Grown in Sir Matthew Decker's Garden at Richmond, Surrey

1720

Theodorus Netscher (1661–1732)

It is said that Lord Fitzwilliam attempted to buy the collection en bloc, but was thwarted, although a few years later, he managed to secure seven important pictures that the syndicate sold on, including masterpieces by Titian, Veronese and Palma Vecchio.

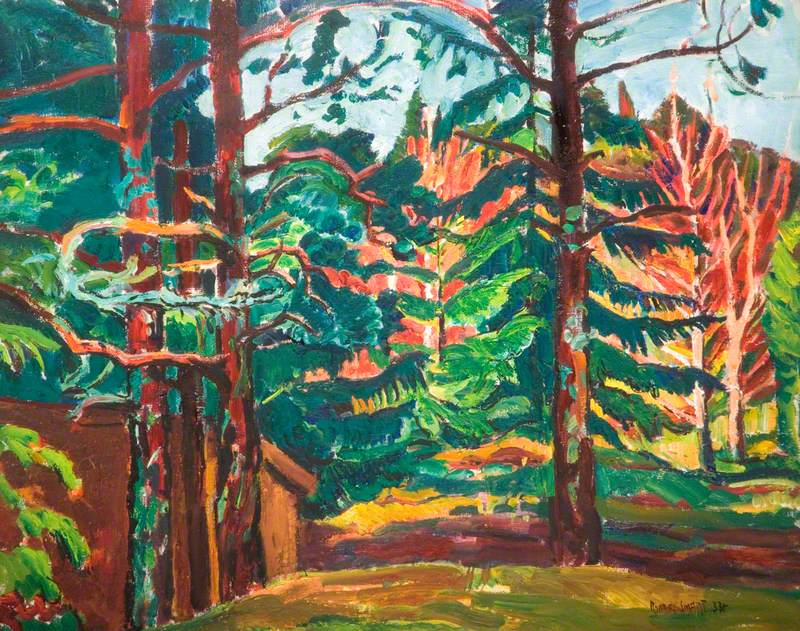

These joined a fine group of Dutch pictures and two huge views of Tudor royal palaces he had inherited from his grandfather, the Anglo-Dutch merchant, Sir Matthew Decker, who is supposed to have grown the first pineapple in England – a feat recorded by a portrait of that very fruit.

To this collection Lord Fitzwilliam added an impressive portrait attributed to Rembrandt, a pair of views of Amsterdam and Haarlem by Berckheyde, and works by French, Italian and Flemish masters. There was also a run of inherited family portraits, including a gruesome double memorial to two Fitzwilliam ancestors who were slain at Flodden Field.

Portrait of a Man in Military Costume

1650

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) (studio of)

A set of painted views of the demesne at Mount Merrion – Fitzwilliam’s estate just outside Dublin – ordered from the Irish artist, William Ashford, reminds us of the source of much of Lord Fitzwilliam’s wealth – Georgian Dublin. Sadly, the only likeness of Fitzwilliam himself in later life is a dim little panel by Henry Howard, although a portrait of him as a young man by Joseph Wright of Derby, resplendent in gold lace, commemorates his MA degree of 1764.

The Honourable Richard Fitzwilliam, Seventh Viscount Fitzwilliam of Merrion

1764

Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797)

Lord Fitzwilliam’s passion for pictures was perhaps exceeded by his interest in prints, collecting thousands of choice impressions, including the finest group of Rembrandt etchings then seen in England, which were arranged in 200 leather-bound volumes, each devoted to a particular artist or engraver – a task to which Lord Fitzwilliam devoted his retirement. Lord Fitzwilliam’s library, comprising some 10,000 volumes collected between 1750 and 1815, was also significant, and is especially rich in illustrated books about travel and the arts. More unusually, in later life he added to the collection 130 illuminated manuscripts, among them ninety-seven medieval Books of Hours.

Despite his high rank and great wealth, Lord Fitzwilliam is a shadowy figure who it seems deliberately left little trace. We have very little information about when or where he acquired his treasures. Nor do we know how he displayed his collection. Bought or inherited – it is a conventional aristocratic collection – Old Master pictures by Titian, Veronese, Rembrandt and other artists – with a pronounced taste for the Venetian School and nudes. He was not a major patron of living artists, preferring books, illuminated manuscripts, and of course his systematically arranged collection of prints.

Lord Fitzwilliam’s bequest to Cambridge University was accompanied by the strict injunction that no works from the Founder's Bequest can be sold or lent. His collection thus remains intact, at the heart of the museum that bears his name. His core enthusiasms – Old Master pictures and prints, music and rare books and manuscripts – remain the great strengths of the Fitzwilliam Museum's collections even today, even though his creation has grown in scope and size to become one of the great university museums of the world.

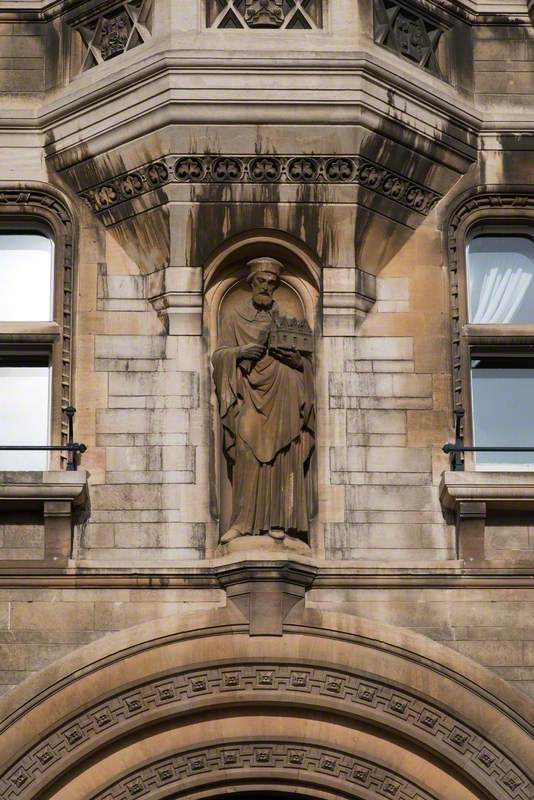

Still housed in the building that Fitzwilliam's bequest paid for, the Fitzwilliam Museum has developed over almost two centuries a distinct character and atmosphere, and – in this its bicentenary year – fittingly honours our Founder’s wish that his Museum promote ‘the Increase of Learning and other great Objects of that Noble Foundation’.

Tim Knox FSA, Director and Marlay Curator of the Fitzwilliam Museum

.jpg)