In the summer of 1936, athletes and journalists from all over the world gathered for the opening of The People's Olympiad in Barcelona – an event held in peaceful protest against the Olympic Games that were about to be held in Hitler's Berlin. But before the first starting gun was fired, machine guns and snipers filled the streets of the city. The Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) had arrived and, along with it, scores of artists determined to take part in the fight against fascism. Two British artists, however, had come to Spain two years earlier.

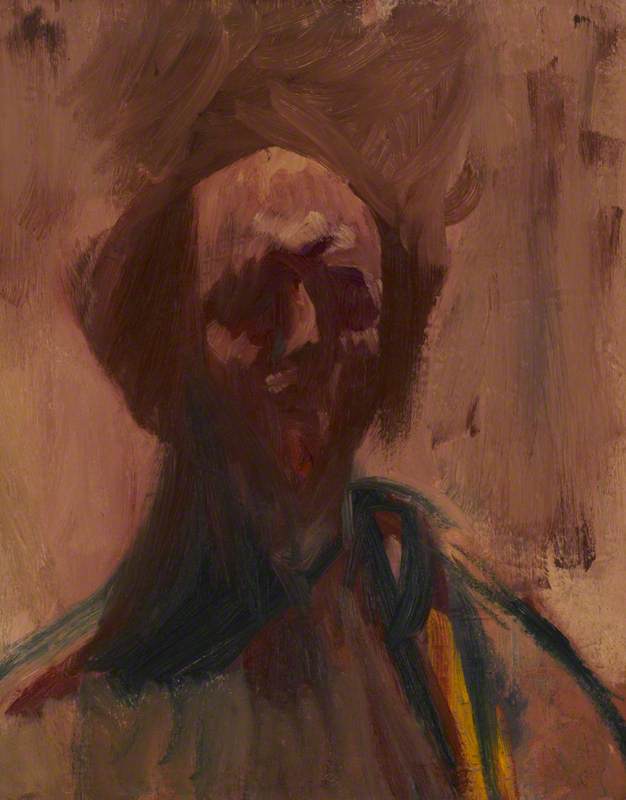

In the summer of 1934, David Bomberg (1890–1957) and Lilian Holt (1898–1983) felt the early tremors of war during their second trip to Spain. Inspired by an earlier trip in 1929, the artists, now married, returned to capture a landscape which had been altered by the threat of conflict. Inspired by the marriage of geology and architecture Bomberg saw in Jerusalem and Petra in the 1920s, the two artists made their way through the rocky amphitheatres around Toledo, Ronda and through the passes of the Picos de Europa, identifying themselves with and against the forms, structures and materials of the land.

Over the years, Andalucía became a second home for Bomberg and Holt, and the place in which they would eventually establish a breakaway Renaissance-style workshop school for a loyal band of students Bomberg taught at London Polytechnic. In London, Bomberg was becoming increasingly frustrated with the lack of critical appreciation for his work. But he would not bend to commercial taste. Here, away from the cold shoulder of mainstream institutions, Bomberg pursued a period of experimentation with charcoal on paper.

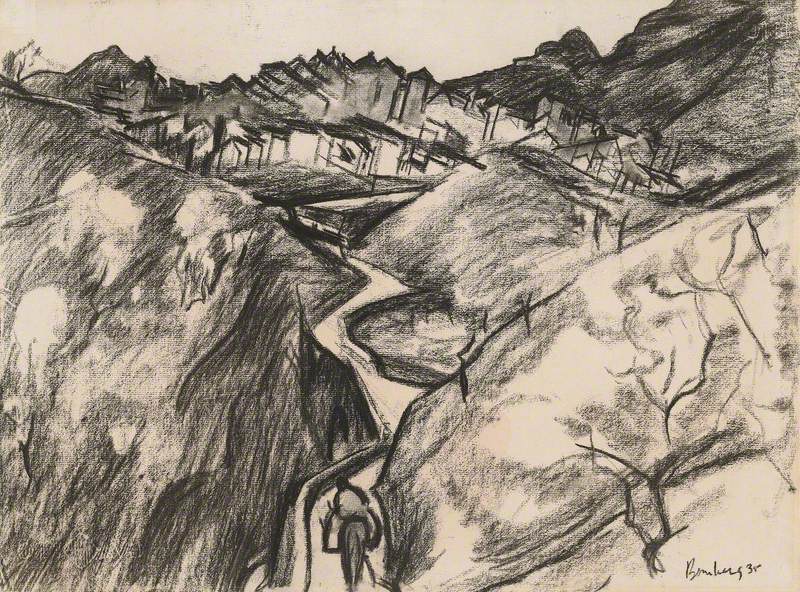

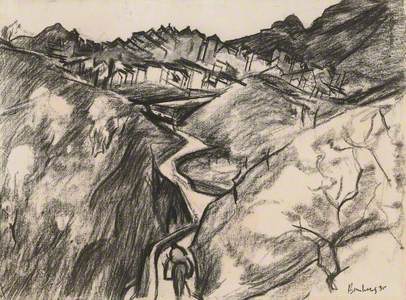

Álora, Andalucía is a Russian doll of charcoal lines: the mountainous horizon line begets the line of rooftops which forms the head-to-foot profile of a sleeping figure, itself spawning the parallel lines denoting the approaching path which cradles the vulnerable traveller. Elsewhere in the composition, the sides of the hills, in their erased patches, reveal profiles of human faces. A traveller's arduous, winding approach to a hilltop settlement becomes a journey down towards the human form. Through Bomberg's lines, we see a land literally shaped by human states and actions.

Journeying to the north, through the Picos de Europa, Bomberg made two drawings of the limestone mountains, both of which reveal a story of human conflict on Spanish earth. In one, Bomberg turns twin peaks into versatile actors. At one glance, the peaks appear as two giants cloaked in charcoal strokes. Erasure marks reveal arms raised in hand-to-hand combat. We look away and return to the drawing, and now find two humble triangular haystacks, tied at the top by thicker, shorter lines of charcoal, and set ablaze by the erasure marks emanating from the top. One scene of mythical violence begets a different, more modern scene of conflict on the ground, in Spain's agricultural heartlands.

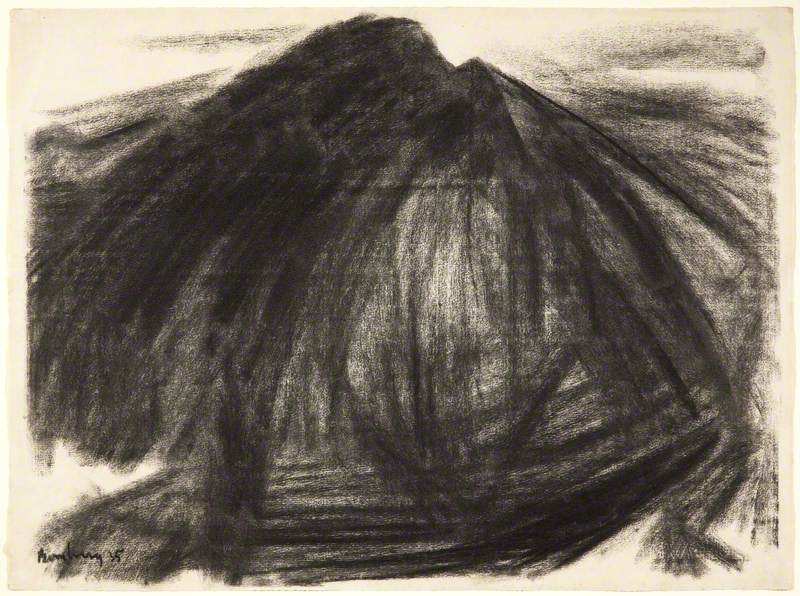

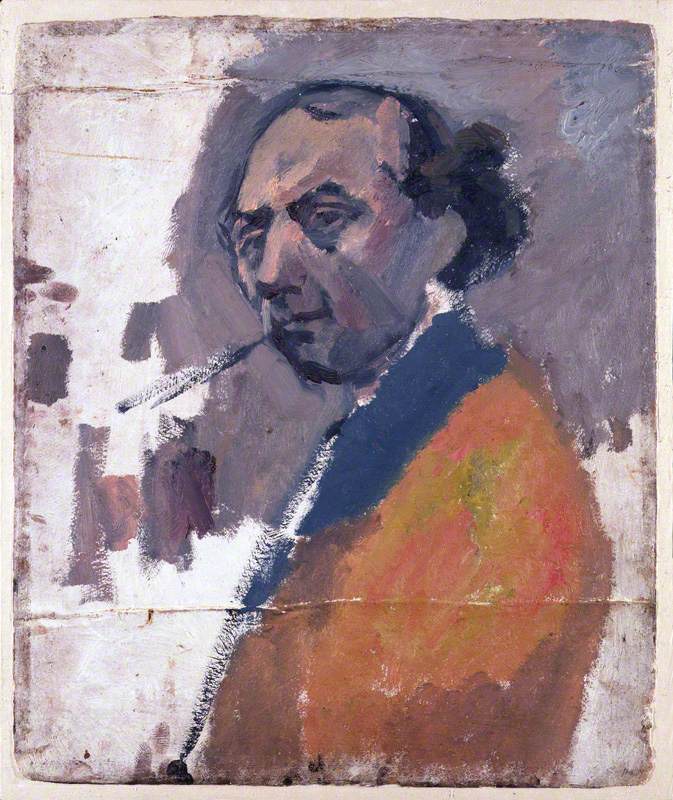

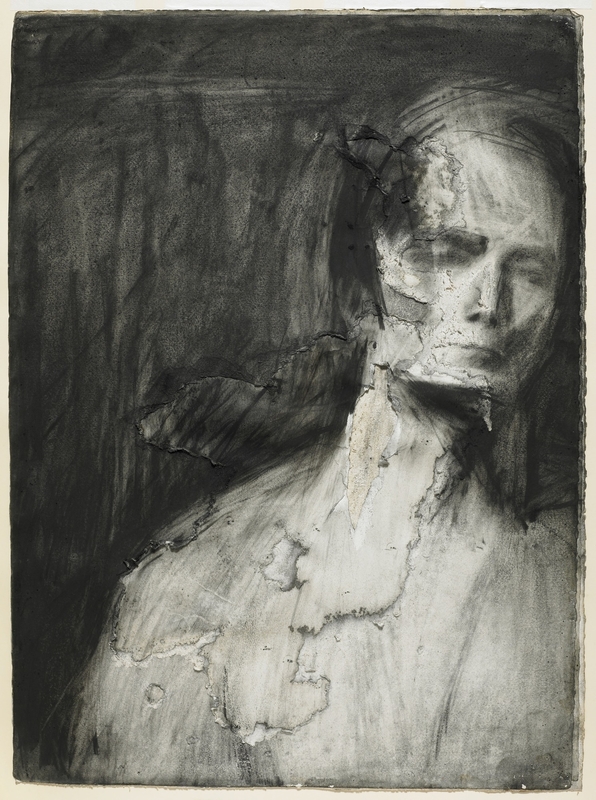

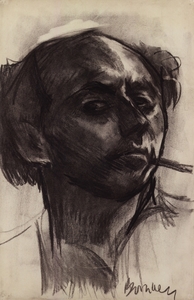

In another drawing composed the same year, Bomberg's mountainous subject becomes a mirror: a mass of charcoal strokes and erasures records a face full of awe and dread at the sublime geological structure witnessed by the same charcoal strokes. Within the structure of the mountain, which resembles that of Bomberg's self-portrait, work with an eraser carves out a space onto which facial features become discernible: a strong triangular jaw provides a scaffolding on which we can notice two asymmetrical eyes composed of hollow charcoal rings. A softer mark of charcoal makes up a mouth. Within an area of the composition mostly made of erasure, Bomberg reveals a face that, like the paper, has been emptied of something.

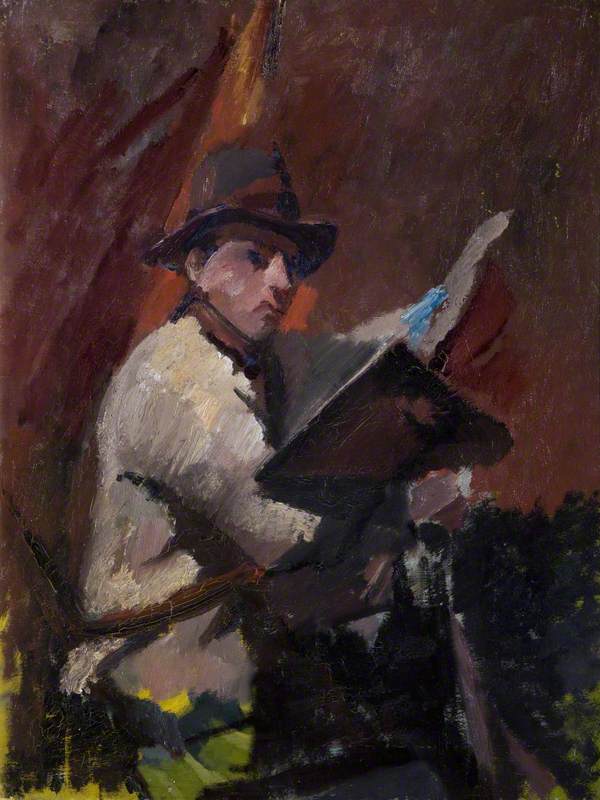

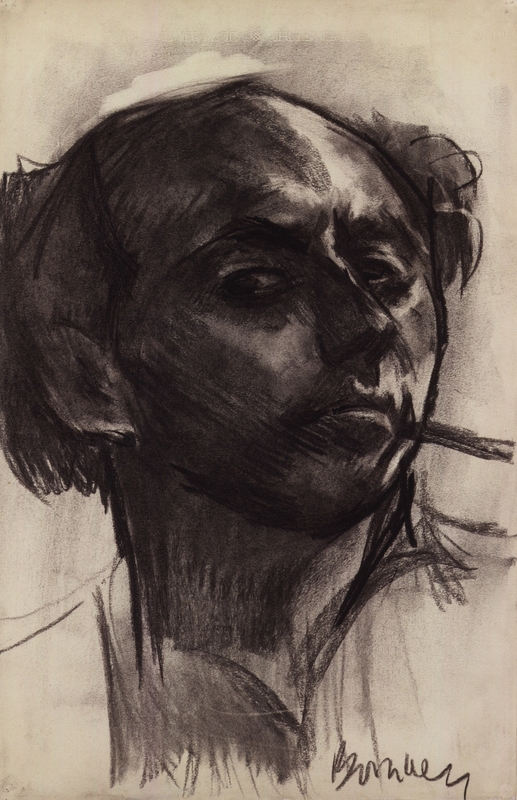

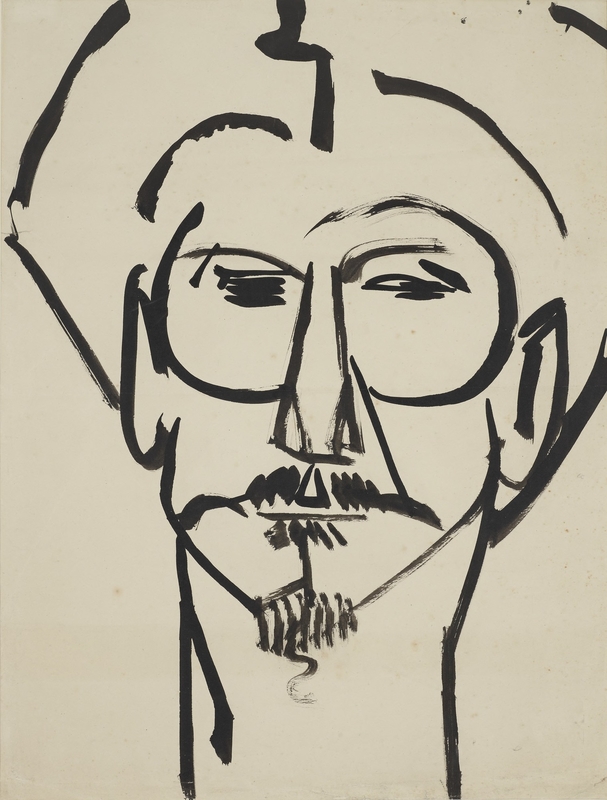

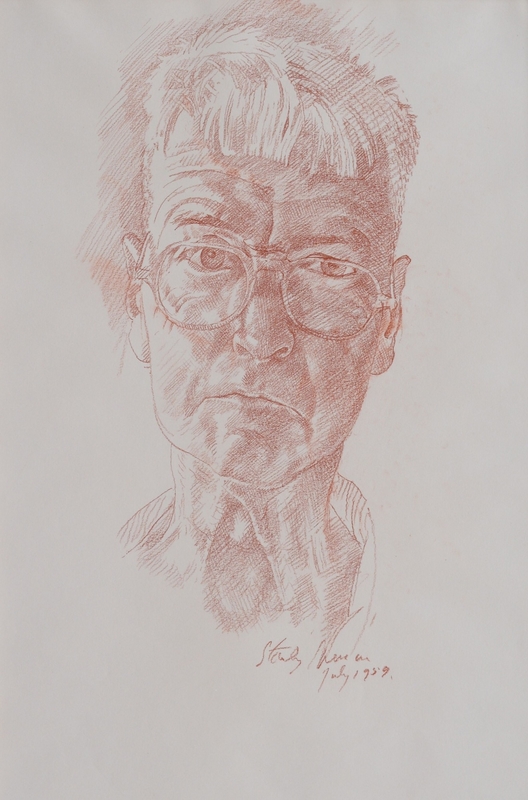

'I found myself…in such close personal communication with the land,' Bomberg said of this period. His landscapes are involved in a larger project of self-portraiture which the artist embarked upon during his time in Andalucía and elsewhere. In a self-portrait, drawing himself with the same bold horizons and mountainous silhouettes present in his landscapes, the artist asks himself and the viewer who he is, and what makes him up. The eyes of David Bomberg throw a quizzical glare at the viewer – an invitation, perhaps, to see the landscape and the human portrait as interdependent.

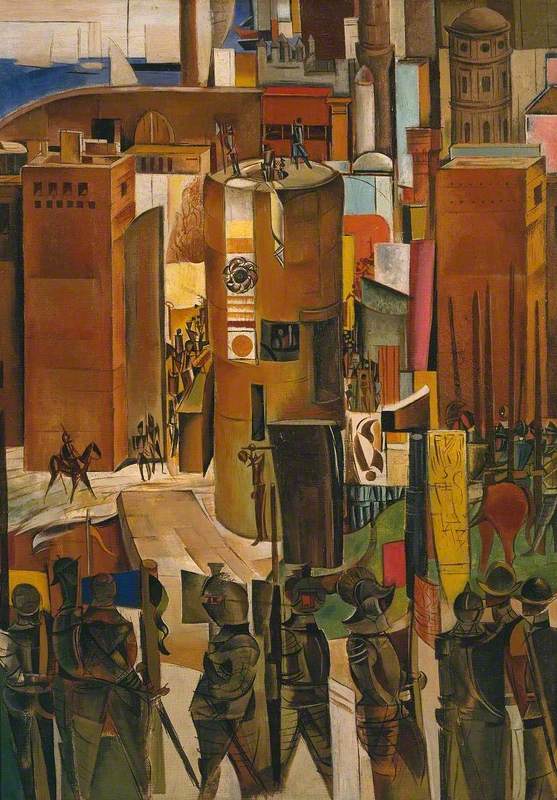

As Bomberg's contemporary and fellow vorticist Wyndham Lewis (1882–1957) documents, by the summer of 1936, Barcelona was under a siege of mediaeval brutality. As Bomberg and Holt made their way back to London, they carried with them the intensity of Spain's landscape as well as its politics.

Returning to Andalucía in 1954, both Bomberg and Holt use charcoal to report landscapes changed by the war they narrowly escaped. The Spanish earth had now become a mass grave for thousands of Spanish civilians murdered by Francisco Franco, and this is reflected in the work of the two artists.

Holt, with short, heavy mark-making, embeds a harrowed face into the rock face. Two haunting eyes are made of repetitive charcoal marks dug out below the cliff horizon. The eyes are asymmetrical and slant towards the bottom-left corner of the composition, towards a burnt mass. At the bottom of the composition, a zig-zag line running through two curved lines reveals a scarred mouth. Speaking somehow to Bomberg's conceptualisation of 'the spirit in the mass', Holt's drawing presents a mass rendered voiceless.

In Bomberg's Ronda, Spain, the artist scatters the remains of his own portrait over a burnt Andalucían landscape. The same curious and cynical eye from the self-portrait David Bomberg (above) is flipped and enlarged, staring at us from the right of the composition. If the eyes of the self-portrait ask us what we are capable of, the eye in Ronda, Spain provides an answer.

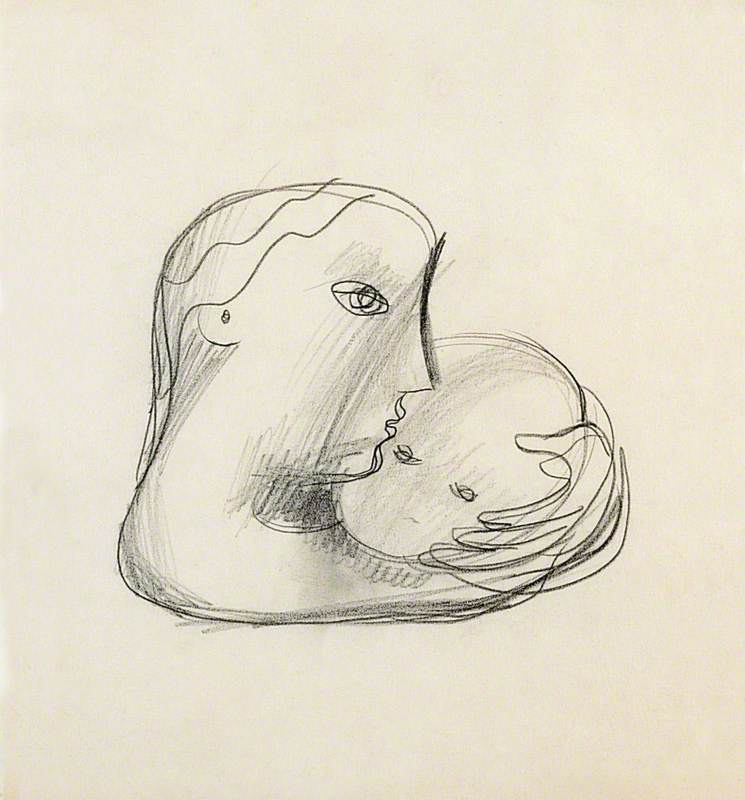

Bomberg was no stranger to the personal cost involved in conflict. During his time fighting in the trenches in the First World War, he lost his brother as well as his friend and Slade School contemporary Isaac Rosenberg (1890–1918). It is hard not to consider this personal history when encountering the drawings in Spain, which meditate on vulnerability and violence in equal measure.

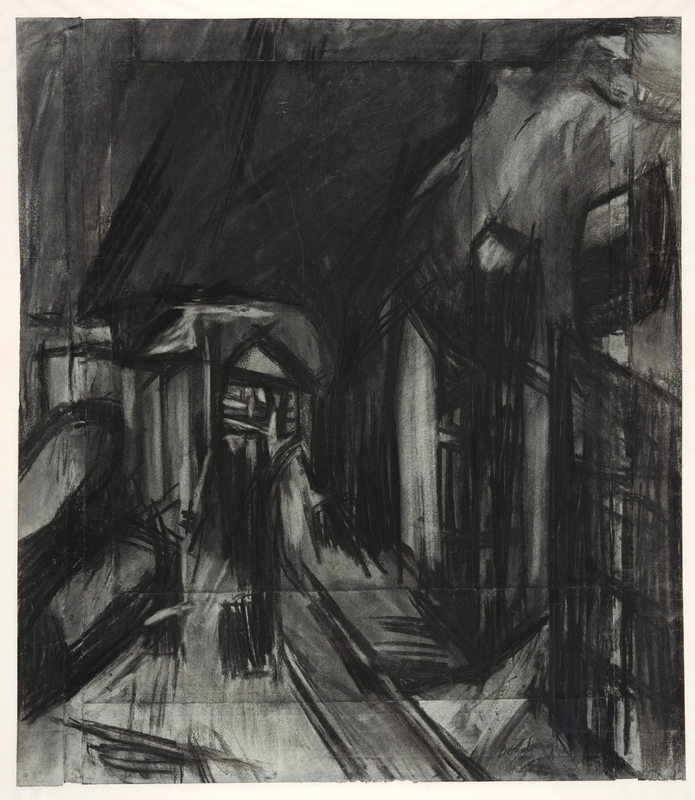

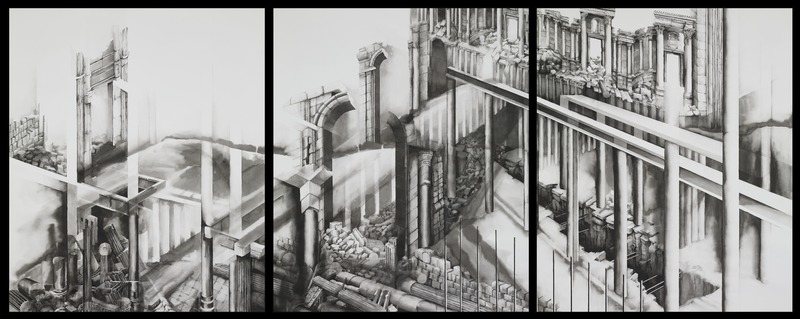

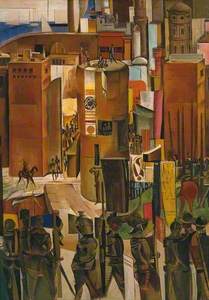

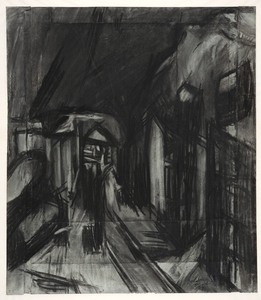

In April 1942, when Spanish refugees fleeing war were arriving in England, Bomberg was commissioned as an official war artist. He spent a fortnight in a bomb store in Burton-on-Trent, where he witnessed weapons being loaded up for use. The bomb store is depicted in a succession of explosively quick, bold, angular lines. To the right of the composition, Bomberg retrieves his ability to blend architectural and human forms, as double gates open, mouth-like, beneath two stern, eye-like windows. Bomberg uses this polymorphic interior to tell a story of how bombs come into use: by human command.

Two years later, there was a tragic explosion at the site, which killed 68 people and left a 100-foot-deep crater. Like his drawings in Spain in 1934, with all their latent violence, the drawing seems to anticipate events to come. But Bomberg's drawings do not see into the future. Rather, they excavate a history of human violence that continues to repeat itself.

Edward Richards, writer

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

Kate Aspinall, 'Artist Versus Teacher: The Problem of David Bomberg's Pedagogical Legacy', Tate Papers, 33, 2020

Richard Cork, David Bomberg, Yale University Press, 1987

William Lipke, David Bomberg: A Critical Study of his Life and Work, Evelyn, Adams and Mackay Ltd, 1967