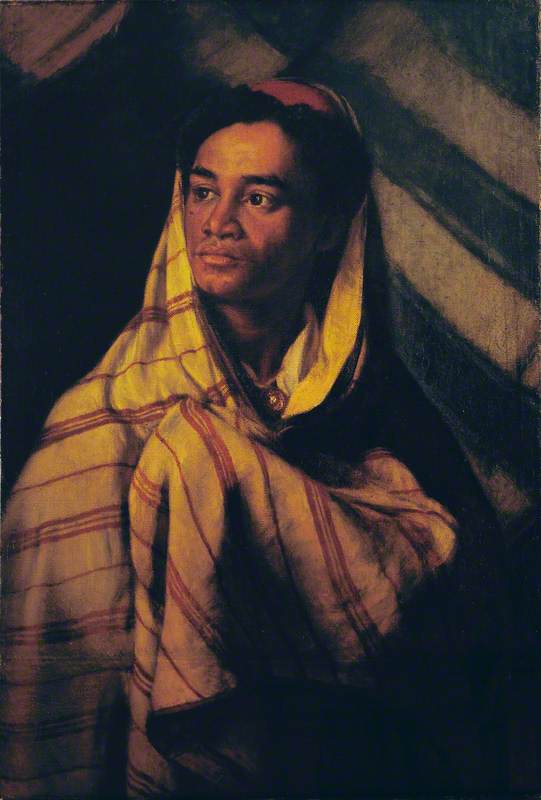

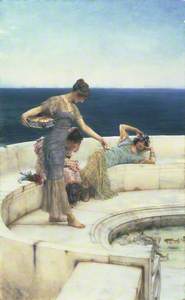

Two Roman women are poised atop marble stairs that overlook a Mediterranean horizon, the Tyrrhenian Sea gently lapping at the shore below. They anticipate the passage of a man, fixated on an engagement ring. The women hold hands and are careful to stay hidden behind the marble balustrade.

We are caught within a larger narrative, with a past, present and a future; will she accept his proposal? Has she been waiting long for this moment? Does the man see the women, or does his deep concentration cloud his awareness of his surroundings?

This is A Foregone Conclusion by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, whose scenes of ancient courtship frequently appeared throughout his artistic career. This work was commissioned by Henry Tate for his wife on their anniversary – an appropriate subject matter.

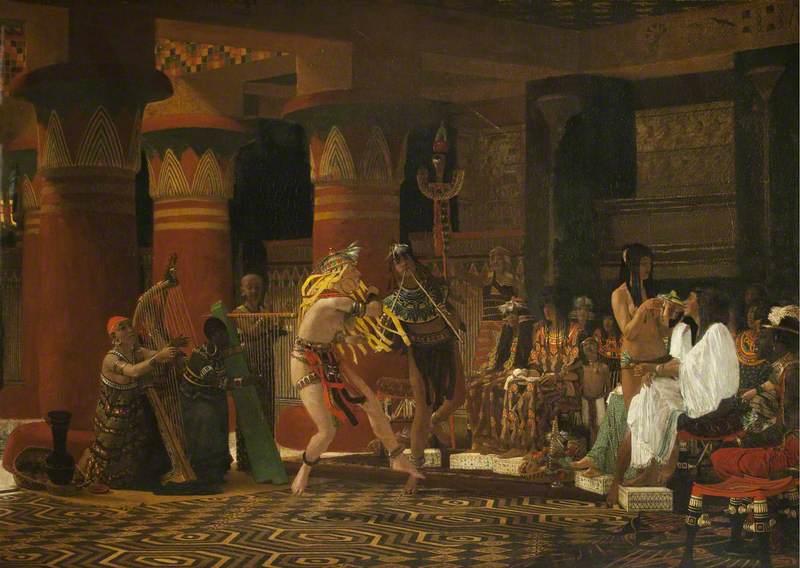

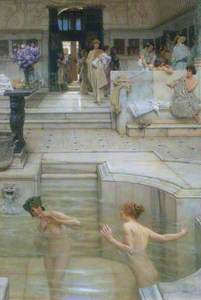

Other tropes Alma-Tadema utilised often were scenes of luxury and excess, sensuality and beauty, paganism, performance and procession, all within an imagined antiquity. It's estimated that three-quarters of his artistic output was inspired by the classical age.

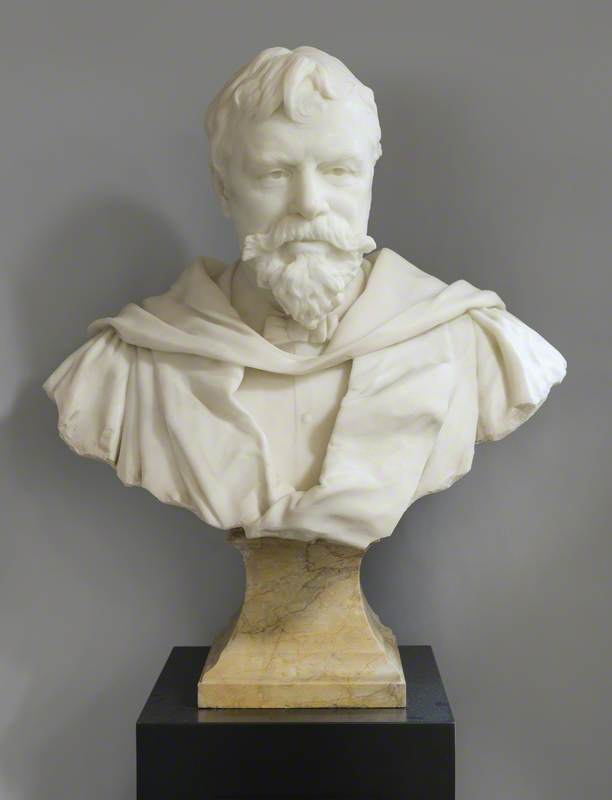

Lawrence (Christened as Lourens) Alma-Tadema was born in 1836, in Dronrijpf, Northern Holland. At the age of 15, he suffered a mental breakdown causing him to abandon his training as a lawyer. During his recovery, he began teaching himself to draw and paint before taking on formal art training at 16. After being rejected from various Dutch art schools, he was eventually accepted to study at the Royal Academy of Fine Art in Antwerp where he trained under Gustave Wappers.

Later, in 1855, he worked in the studio of Louis De Taeye as an assistant. De Taeye encouraged Alma-Tadema to explore classical subjects, stories and art. He fostered an appreciation of historical costuming within his student – it was this training that would become the most influential in Alma-Tadema's artistic career.

Later, with the outset of the Franco-Prussian War, Alma-Tadema moved to London, where he was introduced to the Pre-Raphaelite circle and began studying at the Royal Academy of Arts. He was able to enjoy moderate success within his lifetime, securing commissions from many patrons; the Flemish art dealer Ernest Gambart was a frequent client.

The Alma-Tadema family were given a denizen status by Queen Victoria allowing them legal rights as Dutch settlers in England. He travelled across Italy in search of direct sources of inspiration, gathering photographs of the Pompeii ruins and faded mosaic floors along the way.

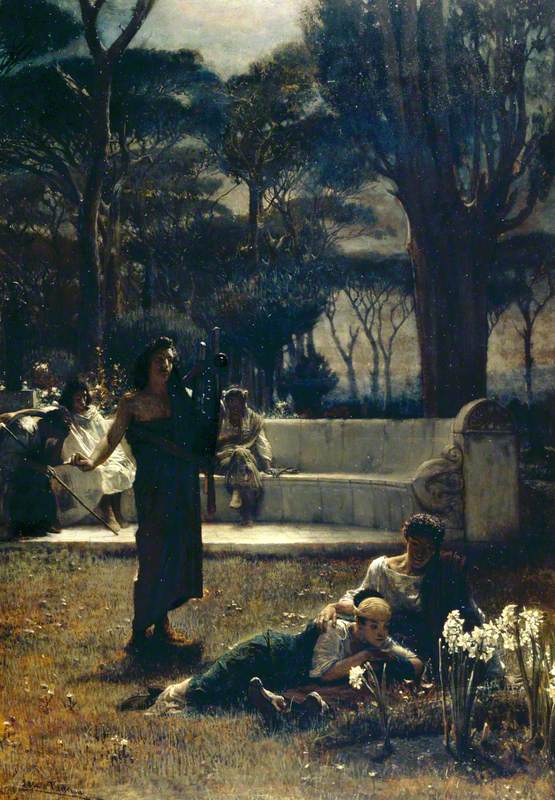

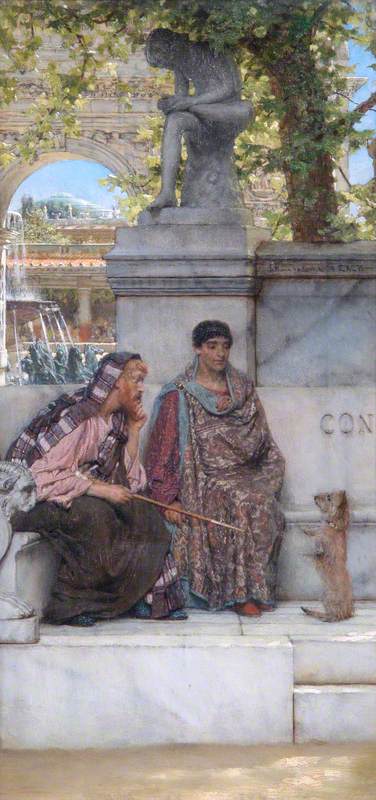

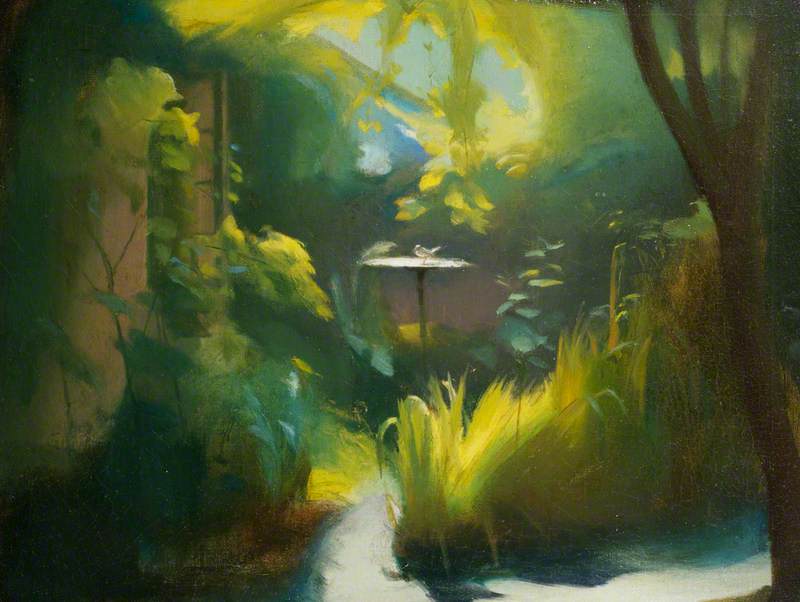

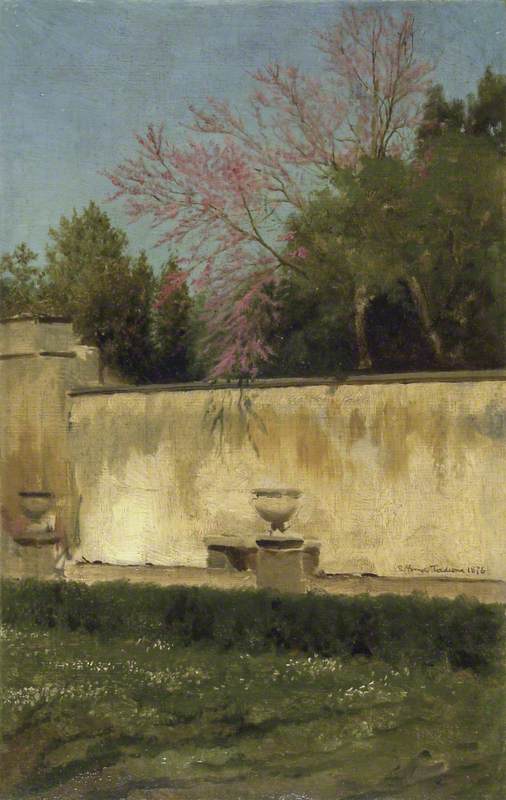

A Corner of the Gardens of the Villa Borghese

1876

Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912)

He was a true academic painter – his classical subjects and his truthful yet beautiful treatment of forms went down well with the academy and critics alike. His works were able to ride the trend of Neoclassicism, with a fresh Romantic influence, and his combination of these two modes contributed to his success.

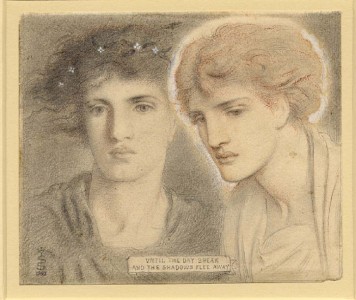

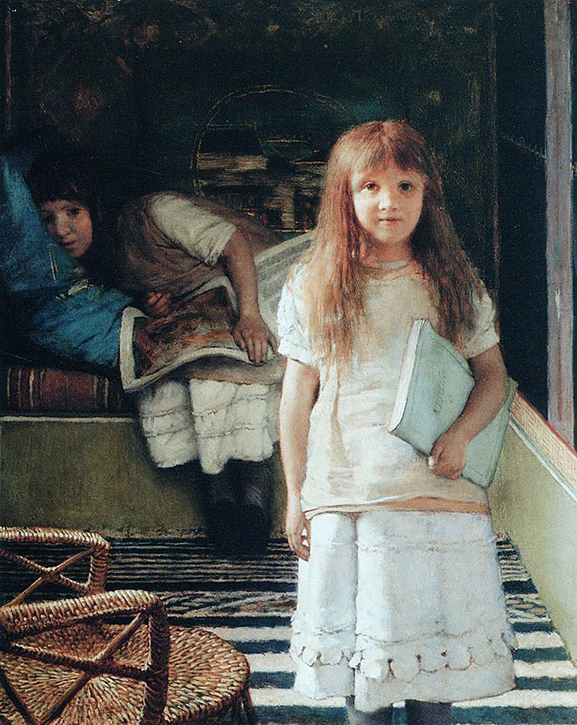

'This is our corner' (Anna Alma Tadema and Laurense Alma Tadema)

1873, painting by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912)

The rest of the Alma-Tadema family was a creative powerhouse. His first daughter, Laurence, was a novelist who worked within multiple genres. His younger daughter, Anna, was a skilled painter of interiors and buildings, as well as a prominent figure in the Women's Suffrage movement. His second wife, Laura, was also a successful Royal Academician painter and was trained by artists within the Pre-Raphaelite circle.

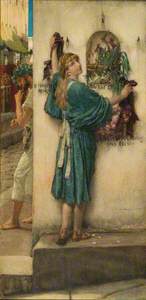

Alma-Tadema's ability to create an intriguing dynamic between the subjects of his works is coupled with a dedication to highly decorative and elegant compositions. The weather is always bright, flowers bloom taller than figures, and classical sculptures and animal skins surround the figures who share knowing glances. Unconscious Rivals and The Secret allude to narratives outside of the pictorial plane through their suggestive titles.

Their relationships give a glimpse into the lives of upper-class Roman women, who gossip about others in their social circles, all while keeping an eye out for interlopers. Alma-Tadema's scenes are hardly ever showing great moments of action or drama, instead opting for minor moments.

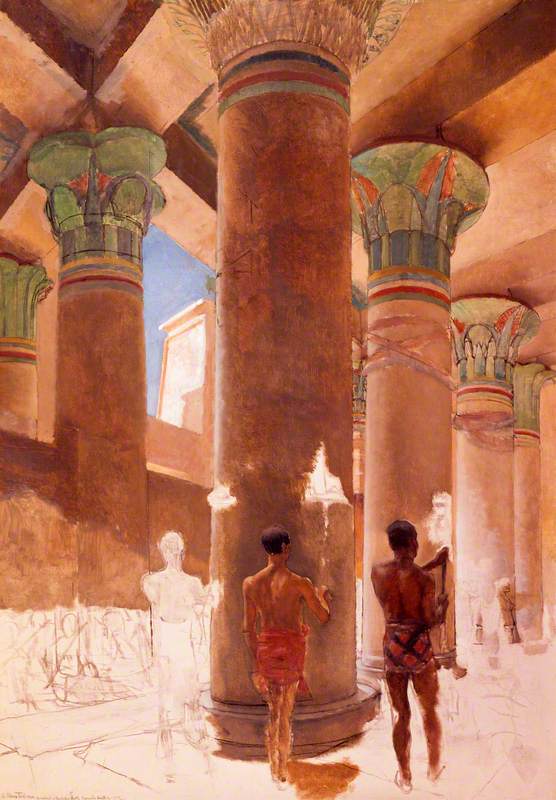

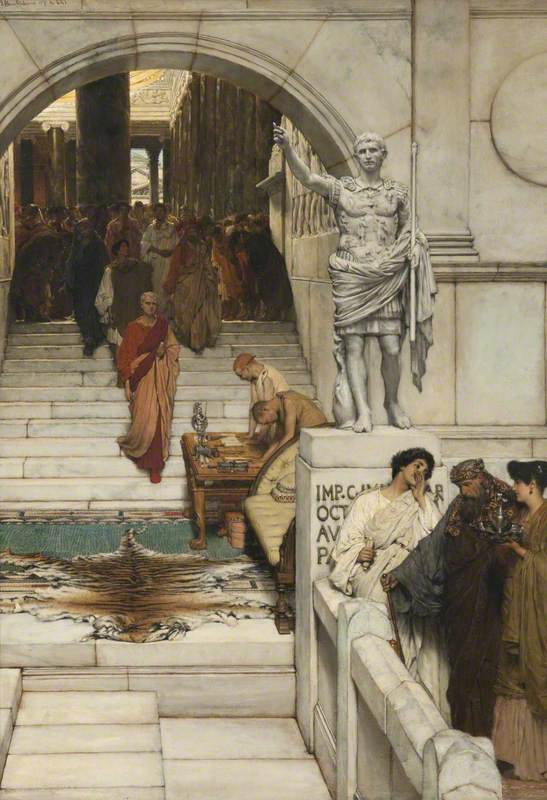

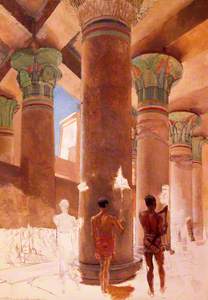

Alma-Tadema's classical paintings are rooted in a Victorian fantasy of an ancient age. His use of different subjects and symbols of ancient history combine to create an artificial classical space. The objects within the scenes are an almost fantastical collage meant to evoke the essence of antiquity rather than to create a scene rooted in truth. Audience with Agrippa is one example of this.

Prominently in the midground of the painting stands a marble sculpture of the Roman emperor Augustus, which overshadows the main figure and subject of the painting, the statesman Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. This suggests his lesser status compared to the emperor.

The sculpture is real: it was excavated in 1863 and is dated to the first century AD. Alma-Tadema's representation is accurate to the original, down to the relief carvings on the breastplate.

Augustus of Prima Porta with a recreation

1st C, marble sculpture discovered in Italy in 1863

However, thanks to research, today it is widely known that this and other statues from the classical and Roman periods would have been painted in bright primary hues. The original Augustus Prima Porta would have been adored in deep crimsons and blues – a complete contrast from the white marble we are used to seeing. In fact, many of the sculptures excavated in the nineteenth century were scrubbed of their pigments in an attempt to keep up the artifice of purity and simplicity and to fit the style of the time.

Audience with Agrippa is a great example of Alma-Tadema's skilful command of texture and form. He was known for being one of the finest painters of marble textures in the Victorian age – a reputation he worked towards after a critic compared his marbles to look more like 'cheese'. John Ruskin, quite unfairly, labelled Alma-Tadema as the 'worst painter of the nineteenth century'.

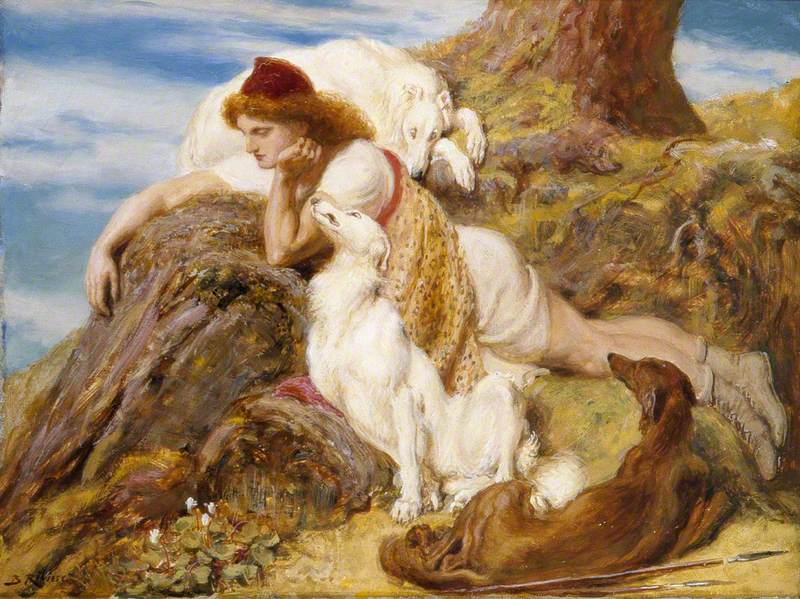

Though not formally considered a Pre-Raphaelite artist himself, Alma-Tadema's approach to aestheticism and Romantic style aligns closely with Pre-Raphaelite values. The Pre-Raphaelite influence is seen in the sensual pose of a Roman woman, with glazed eyes staring into the middle distance.

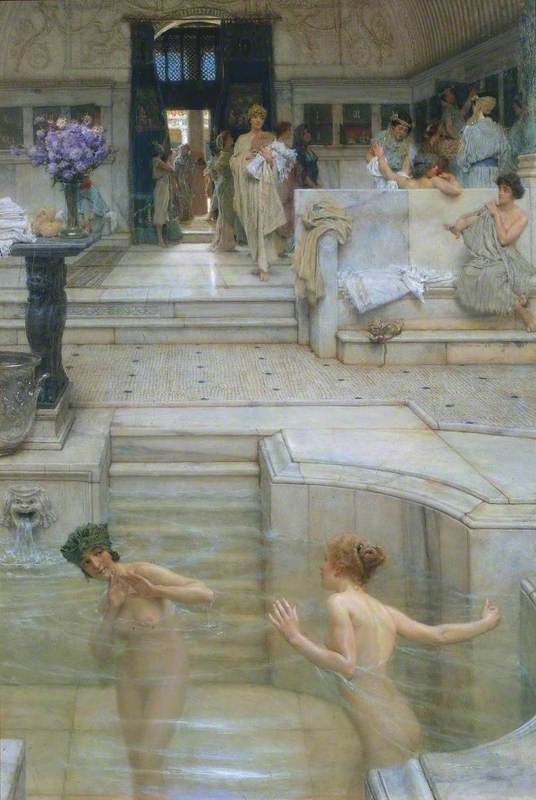

Around the turn of the century, his colour palette became lighter. He focused on luscious pink and purple hues in clothing and flowers, greens and ambers in jewellery and furnishings, all against gleaming white marble. However, the divergence between Alma-Tadema and the Pre-Raphaelites is seen in the periods of history they choose to depict, with the Pre-Raphaelites opting for medieval or Biblical narratives and scenes.

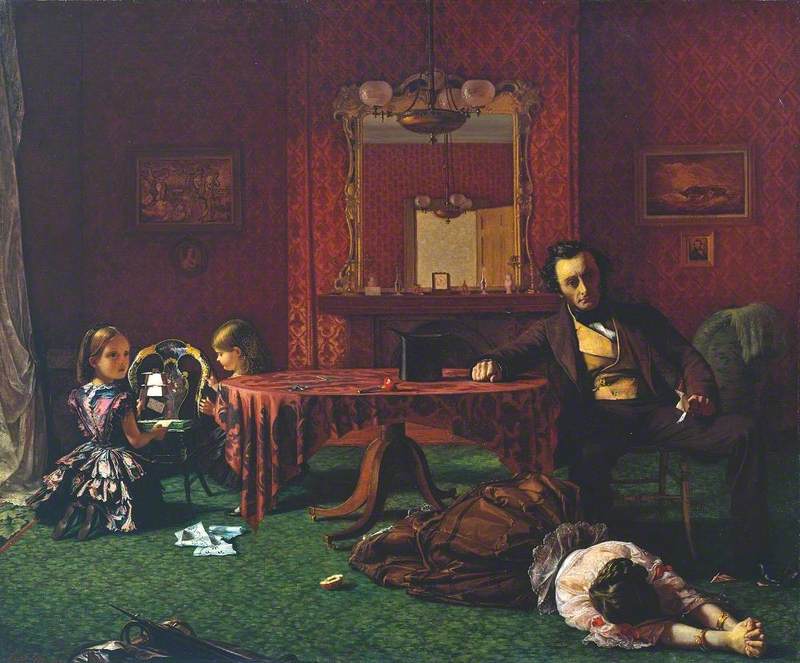

Critics of Lawrence Alma-Tadema believe the figures of his paintings are mere 'Victorians in togas', no more than modern models playing dress up. The Picture Gallery of 1874 seems to be an example of this.

The figures are wearing heavily draped togas, yet are historically displaced and are shown in a Victorian gallery or parlour. They admire paintings on the walls in decorative frames, hung on chartreuse walls. Alma-Tadema here anachronistically combines nineteenth-century interiors and decorative elements with archaic models, to create an imagined, otherworldly space. It acts as a gallery of his own, combining visual languages and motifs that speak to him.

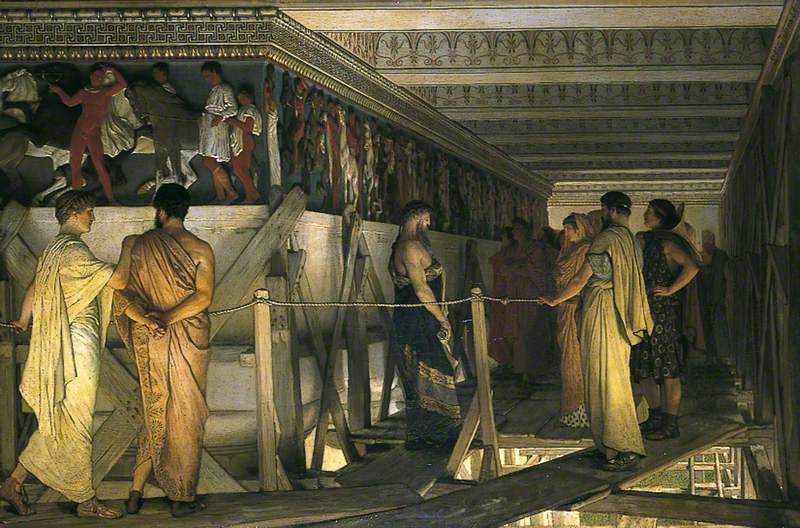

Pheidias and the Frieze of the Parthenon

1868/9

Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836–1912)

Though other eminent Victorian painters tend to overshadow the life and paintings of Lawrence Alma-Tadema, his works are no less beautiful and detailed, and they are often filled with humour. They are loud, bustling processions, such as in Spring (in the Getty collection), but can also be subdued and lazy, as with his Silver Favourites.

His works are held in many UK collections, including Bristol Museum & Art Gallery, the Ashmolean in Oxford, and the Tate Britain in London.

Isabel Booth-Downs, writer