I came in from the cold of a Scottish winter to warm myself in the Scottish National Gallery, and because I couldn’t resist, not on this or any other trip into Edinburgh. Inside the gallery all was calm. People pottered around in their hats and gloves, and children were spread out on rugs on the floor, crayons scattered around them – a picture of artistic domesticity. I wandered until I found myself fixed in front of a grand tableau that commanded the space with its size (143 x 168.3cm) and its three otherworldly glowing figures, The Ladies Waldegrave by Joshua Reynolds.

Was I drawn to it because the women seemed so close to me in age? What was their story? How could I possibly identify with three needle-working women with foot-high gray-powdered hair? Through stepping back, and taking a closer analysis of this painting I’ve come to find that these women are depicted as far more autonomous and powerful than the casual observer might assume.

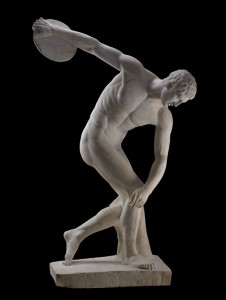

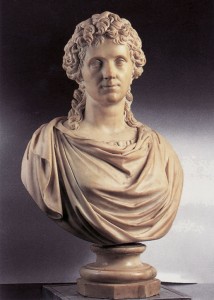

The Ladies Waldegrave was commissioned as a portrait of Lady Charlotte Maria, Lady Elizabeth Laura, and Lady Anna Horatia Waldegrave, the daughters of James Waldegrave, the 2nd Earl Waldegrave and his wife Maria Walpole. This was certainly a calculated commission, and its prime intent was to attract attention to the three marriage-aged girls. Due to its aspirational social function the painting The Ladies Waldegrave has often been discounted in scholarly circles as a luxurious yet vapid portrayal of socialites posed as the three graces, and has been widely ignored as anything more than a billboard for attracting men. However, in classical and neo-classical art the three graces are nearly always pictured in the midst of a dance with two figures facing forward and the central figure with its back to the viewer, as is represented most famously and memorably in Raphael’s The Three Graces or Sandro Botticelli’s Primavera, while The Ladies Waldegrave decidedly resists this trope.

By the time The Ladies Waldegrave was painted in 1780 Joshua Reynolds had become Sir Joshua Reynolds, knighted by King George III and appointed as the first president of the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts in London. A painting commissioned by a high-status artist such as Reynolds nearly guaranteed its appearance on the walls of the Royal Academy, a place frequented by the fashionable of London, and well within the line of sight of many wealthy suitors for these three women. Whether due to this enticing Georgian portrait, or their actual real-life charms, things worked out well for the Waldegrave sisters. Like the ending of a Jane Austen novel Elizabeth married her cousin the Earl Waldegrave, Charlotte the Duke of Grafton, and Anna the Admiral Lord Hugh Seymour.

Rather than representing the three graces, The Ladies Waldegrave is arranged in a manner that more closely mirrors a modified depiction of the three fates. Instead of frivolously dancing, the Waldegrave girls are shown industriously employed in lace-making. The first sister, Charlotte, holds out a long measure of white silk, while the second sister measures it by wrapping it around a skein. This closely identifies with the actions of the fates or the Moirai as they are known in Greek, the three white-robed agents of destiny who were believed to determine the length of every mortal’s life. The Moirai were mysterious beings of extreme power, whose judgement was said to be honored even by the ultimate patriarch of the ancient world, Zeus. Of the three goddesses Clotho spun the thread of life, Lachesis measured it, and Atropos cut it. While it would be inappropriate to depict a society lady searching for a husband as an agent of death, Lady Anna Horatia who is seated in the place of Atropos is instead embellishing a length of tulle on a thick ebony tambour frame, rather like a beautiful spider’s web or a wedding veil – both useful when in the market for ensnaring beaux.

Depicting The Ladies Waldegrave as the fates was a bold and witty statement by Reynolds. Having reached the apex of his career and getting on in years, he was free to use his commissions to experiment with subjects that interested him such as classical Greco-Roman themes that surface in so many of his later works. Painting the Waldegrave ladies as the fates was perhaps a cynical social commentary on the nature of the commission, but it was also a respectful allusion to the power these women held in controlling their own destinies. Rather than at the mercy of their parents or the whims of suitors, these women are shown as the agents of fate, spinning their own lives into being with an air of calculation and confidence.

Caroline Croasdaile, writer