Catherine Maria 'Kitty' Fisher was the most celebrated courtesan in England in the 1760s and was one of the first celebrities to be famous simply for being famous.

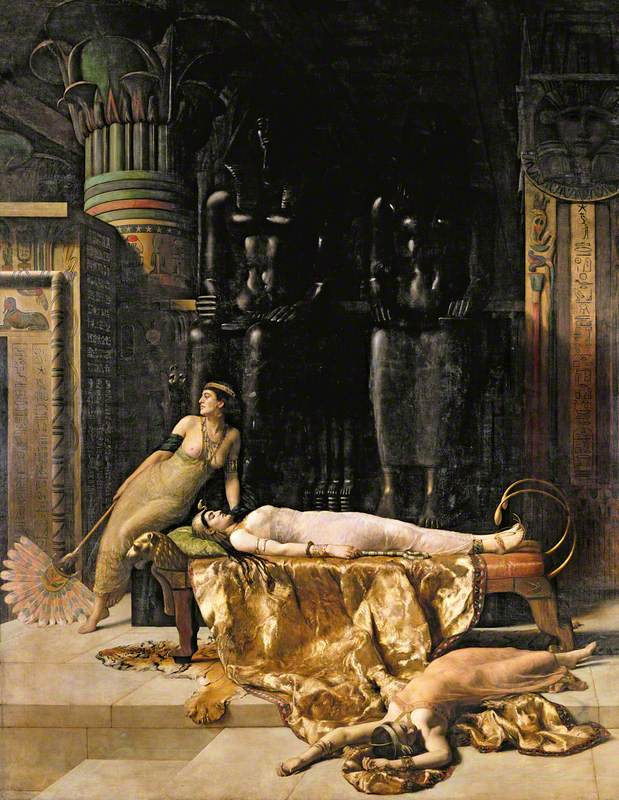

Kitty Fisher (1741–1767) as Cleopatra Dissolving the Pearl

1759

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

Her career as a high-class prostitute allegedly began after she was seduced then deserted by a young army officer. Using her wit, charm and beauty, she rose to fame through high-profile liaisons with wealthy and powerful men. London society was both scandalised and fascinated by her behaviour, and she cultivated her celebrity status by collaborating with writers and artists to promote her public image.

Kitty Fisher as Cleopatra Dissolving the Pearl was painted by Joshua Reynolds in 1759, probably commissioned by her client Sir Charles Bingham. In this sexually charged image, Reynolds depicts Kitty as Cleopatra in a scene recalling a lavish banquet held in honour of Mark Antony, at which the Egyptian queen dissolved a giant pearl in vinegar and drank it. Similar stories were told about Kitty, who was notorious for her extravagance. According to Casanova, she once ate a £100 banknote on a slice of buttered bread. The association between Kitty and Cleopatra – another woman known for her beauty, lasciviousness and command over powerful men – was not lost on contemporary audiences.

Kitty was painted by Reynolds at least four times, fuelling speculation they were lovers. For Kitty, being painted by the most celebrated artist of the day was a powerful act of self-promotion. Equally, befriending and painting a woman who moved among the social elite yet flouted the codes of polite society provided Reynolds with immense publicity and let him push the boundaries of portraiture in a way that would have been unacceptable for more conventional women.

This painting was not among the original 63 works left to the nation by Edward Cecil Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh, in 1927 as part of the Iveagh Bequest. Instead, it was bequeathed to Kenwood by his son Lord Moyne in 1946. Today the painting hangs in the music room and is one of the most intriguing and scrutinised of Kenwood's Georgian beauties.

Louise Cooling, curator at Kenwood, English Heritage