He has frequently made the headlines for his theatre and television work, but the one constant in John Byrne's career is his art. The author of The Slab Boys, a set of three plays that drew on his time working in a 1950s carpet factory in Paisley, is rarely away from a paintbrush.

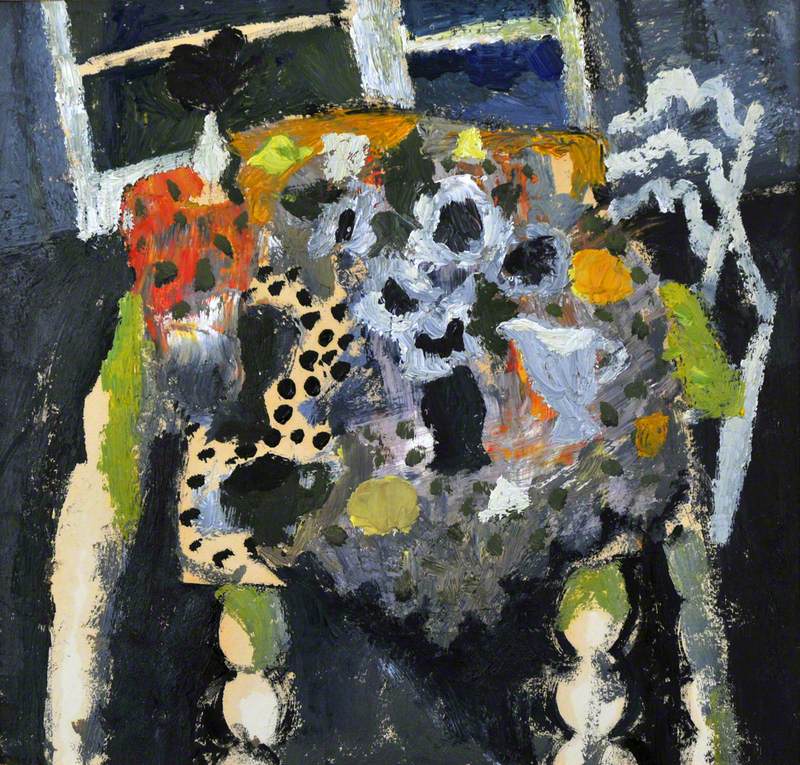

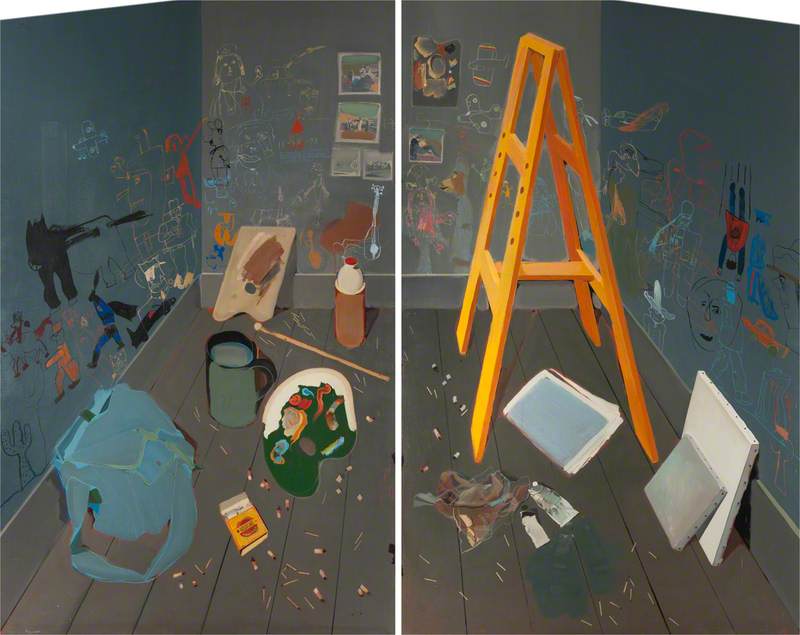

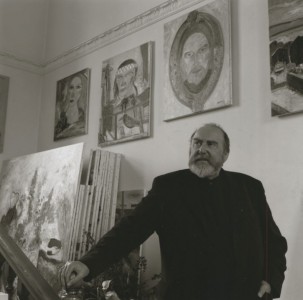

'I've been working every day in my studio and producing work of a new nature,' the 82-year-old said in 2021, adding that blindness in his right eye had forced him to change his style. 'I'm very excited about it. I've been busier than ever, painting from morning till night, seven days a week.'

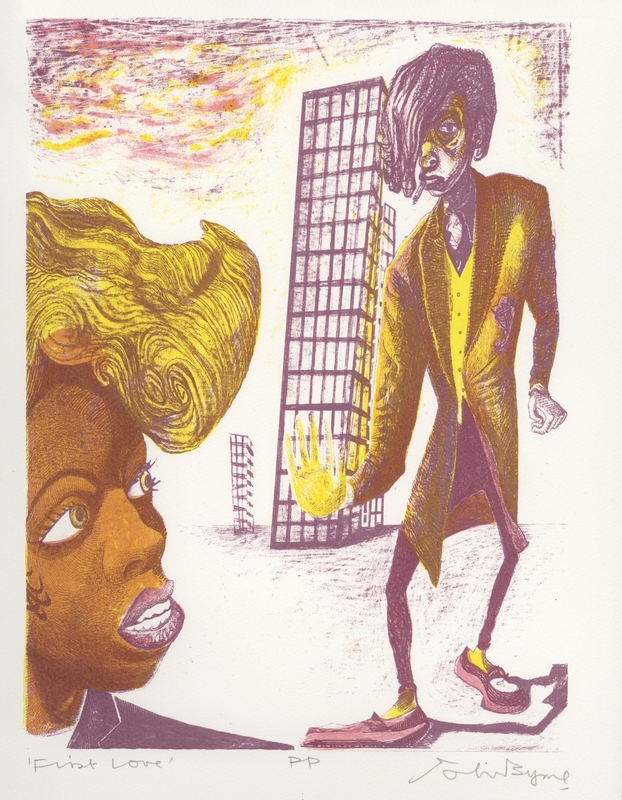

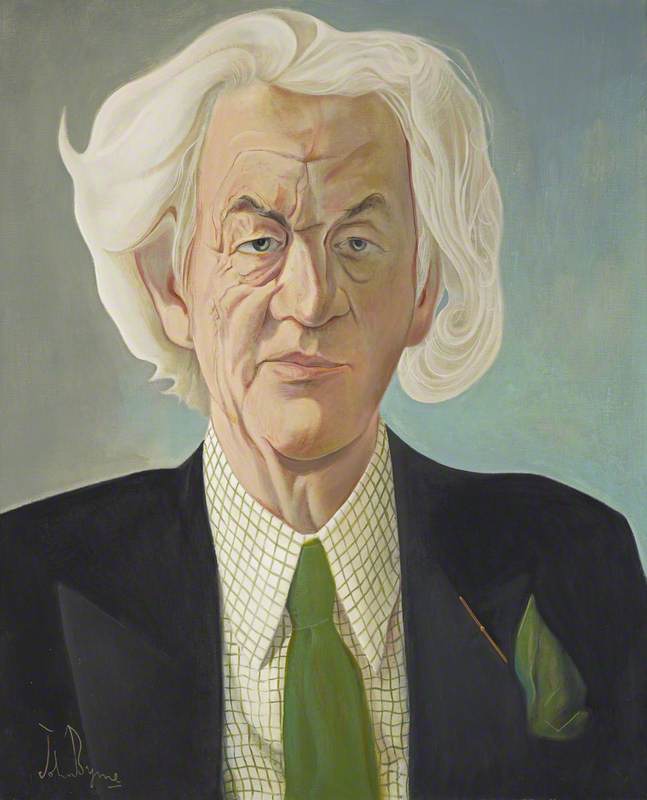

Byrne is a man who thinks visually. Even his scripts are decorated by illustrations of the characters. With assured lines and exaggerated features, they sport kiss-curls and Teddy-boy quiffs, their dresses voluminous, their jackets buttoned up. Whether pen-and-ink cartoons or vivid pop-art portraits, they show a keen satirical eye.

He is a natty dresser himself, with a taste for layers of tweed beneath his striking grey beard. As an artist, he is just as sharp an observer of period fashion.

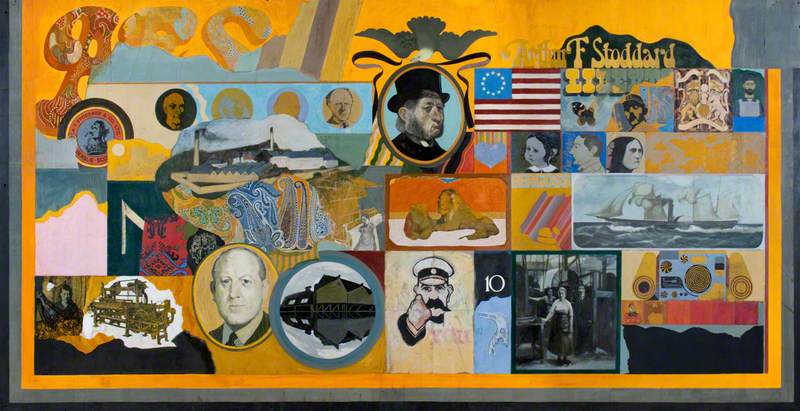

His route into the artistic life was hard-won. Having left his Catholic grammar school before sitting his final exams, he effectively served his art-school apprenticeship in Paisley at Stoddard's carpet factory, which he fictionalised in his plays as A. F. Stobo & Co. Here, he would grind powdered colour for his superiors in the design room.

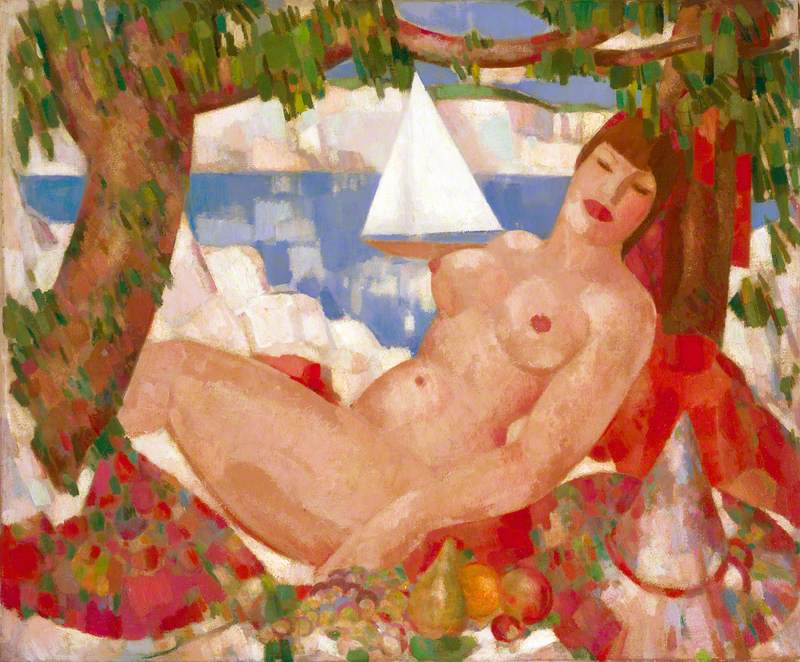

He enrolled at the Glasgow School of Art (GSA) in 1958 and focused on the traditional skills of life drawing, painting and still life. After a year at Edinburgh College of Art, he graduated from GSA in 1963, having received the Bellahouston Award for painting. He also won a scholarship to Italy, where he would marvel at frescoes by Giotto as well as paintings by Duccio and Cimabue from the early Renaissance.

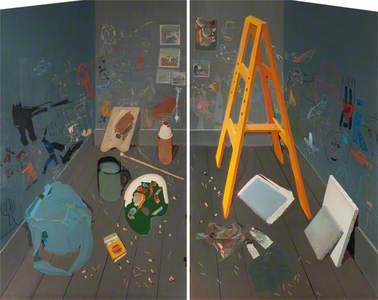

Not part of any movement, he found it difficult to break into the London art world of the 1960s. Instead, he earned money as a book designer, worked in the graphics department of Scottish Television, and even returned to Stoddard's as a carpet designer.

Frustrated by his lack of artistic success, he adopted the pseudonym Patrick, supposedly his 72-year-old father (whose name was indeed Patrick). At art school, he had developed the knack of mimicking the great painters of the past, so to adopt the mannerisms of an outsider artist came easily to him. Much to his amusement, he found that galleries were suddenly interested in this undiscovered primitive talent.

It led to his first solo show at the Portal Gallery in Mayfair in 1967 and, after revealing his true identity, he became a full-time artist. The Portal Gallery didn't seem to mind, and continued to exhibit his work.

It was under the name of Patrick that he provided the cover artwork for The Beatles Ballads, a 20-track compilation album, complete with faux-naïve illustration of the Fab Four hunched together, while big cats, rabbits and butterflies gathered around. It was not released until 1980 but the design had been a contender for The White Album as early as 1968.

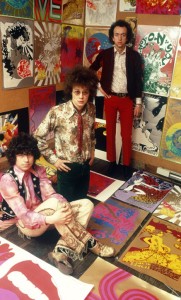

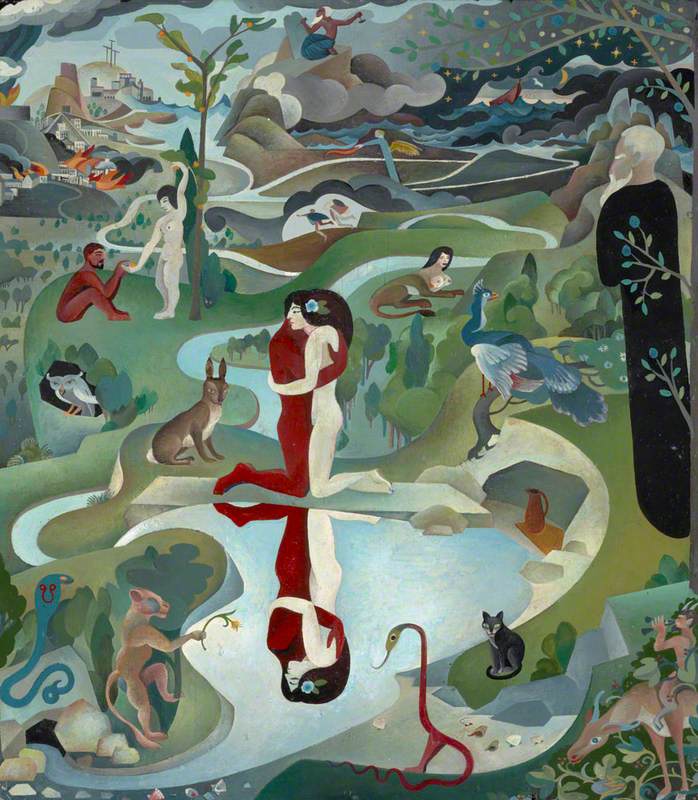

As well as working as a theatre designer, Byrne also illustrated album covers for Gerry Rafferty, Donovan, The Humblebums, Billy Connolly and Stealers Wheel. Mostly done under the guise of Patrick, they were a whimsical blend of portraiture and the natural world, with a deliberate disregard for perspective and an unapologetic love of decorative detail. It was not until the mid-1970s that he shook off this persona to create work under his own name.

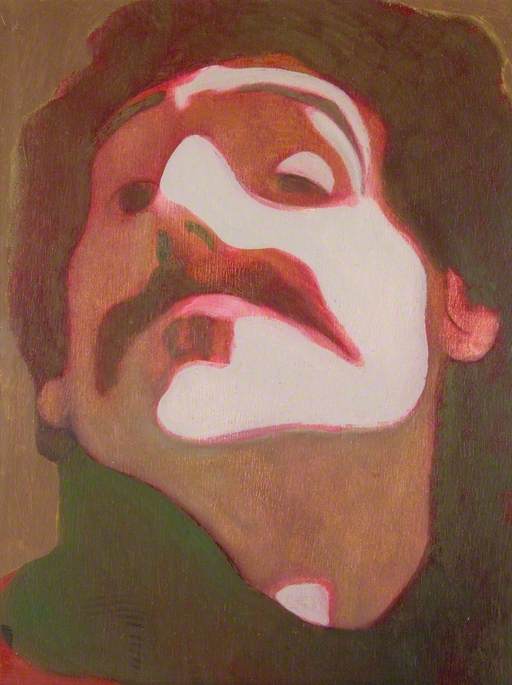

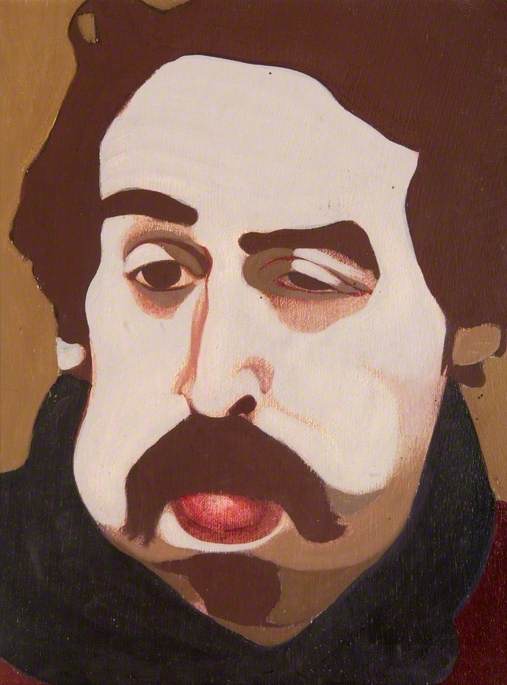

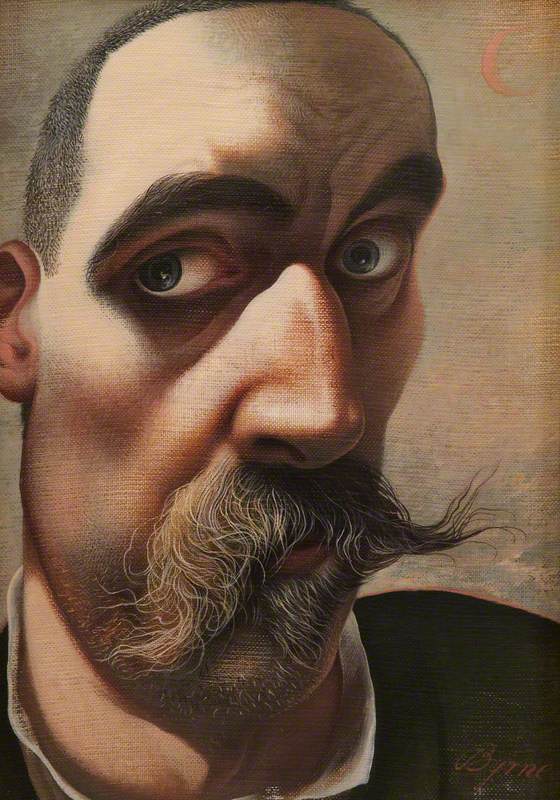

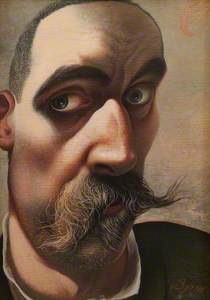

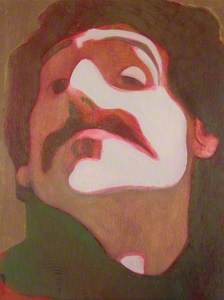

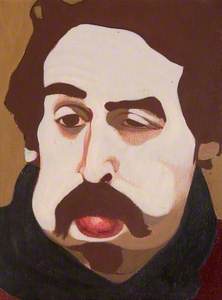

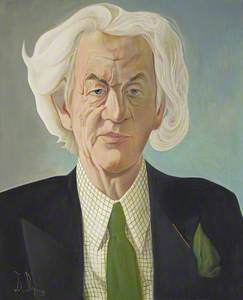

Just as Phil McCann, the central character in The Slab Boys, is a close match for Byrne, so Byrne as an artist has returned repeatedly to the self-portrait. Making himself explicitly the subject of a painting is his way of checking in on himself.

'You're here on Earth to ask why you're here on Earth, not to avoid the question at all costs,' he said in 2008. 'The great many of my self-portraits aren't the most flattering. Some of them are, when you're feeling like a human being and what a great life. But mostly they're not. I'm always very suspicious of people who say they don't do self-portraits, the implication being they're so modest. What makes you so full of yourself that you think you're of no interest to anybody – meaning the opposite?'

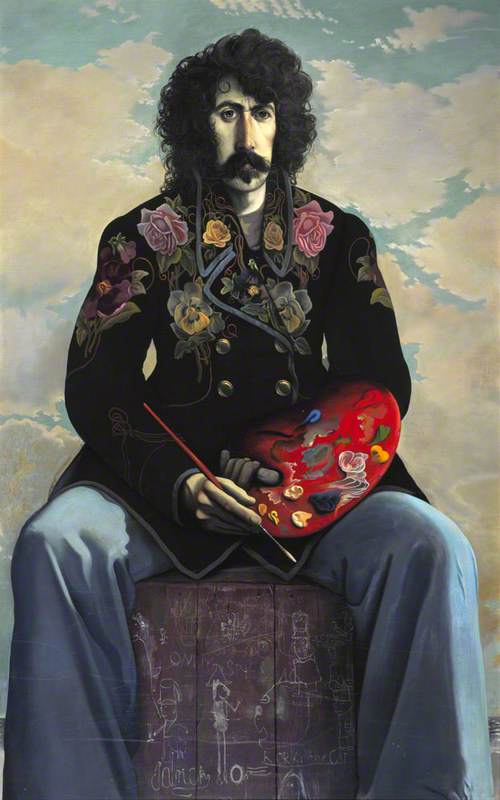

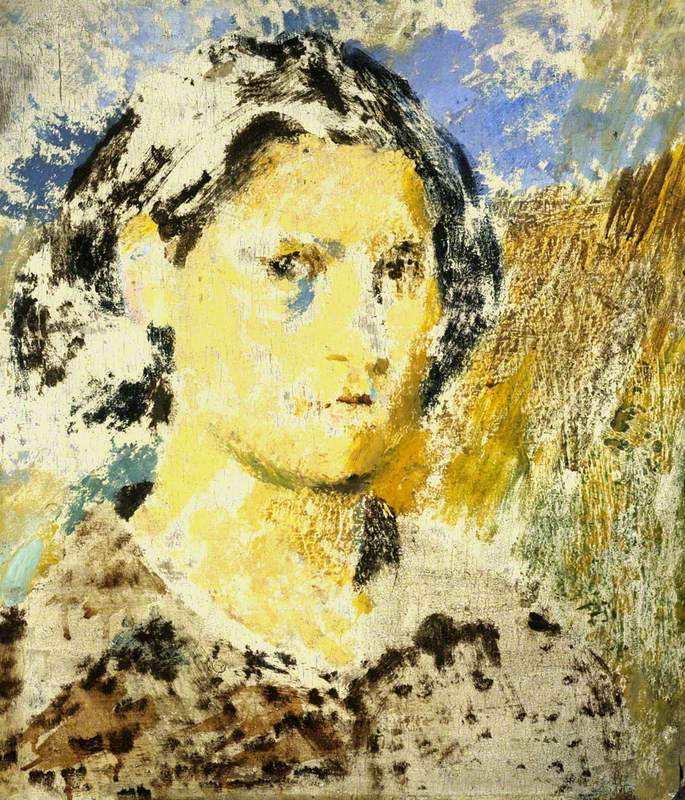

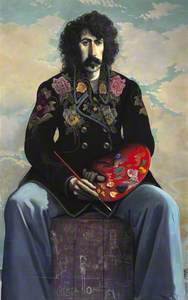

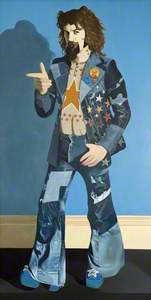

If he hid behind a persona as Patrick, he has revealed himself in forensic detail in his self-portraits. In Self Portrait in a Flowered Jacket, we catch him in the early 1970s in the role of an artist. His sober expression belies an extravagant floral jacket, a mound of curly black hair and a head that seems to be in the clouds.

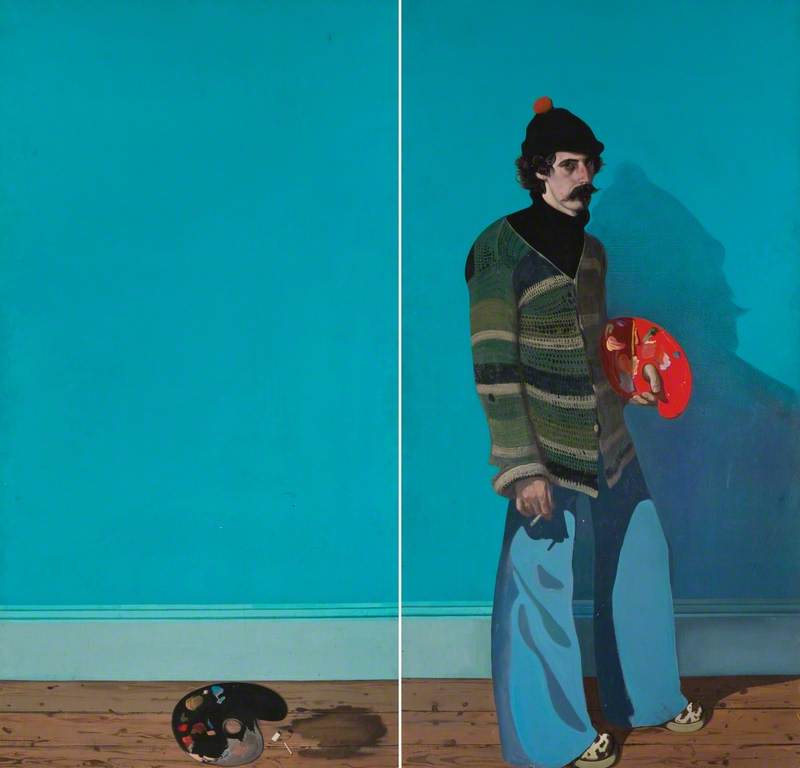

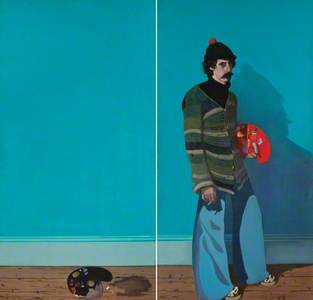

A couple of years later in Self Portrait with Red Palette, he is in a more morose mood, still clutching his paint palette but now casting an expansive shadow on the turquoise wall behind him, a look of surliness in his darkened eyes.

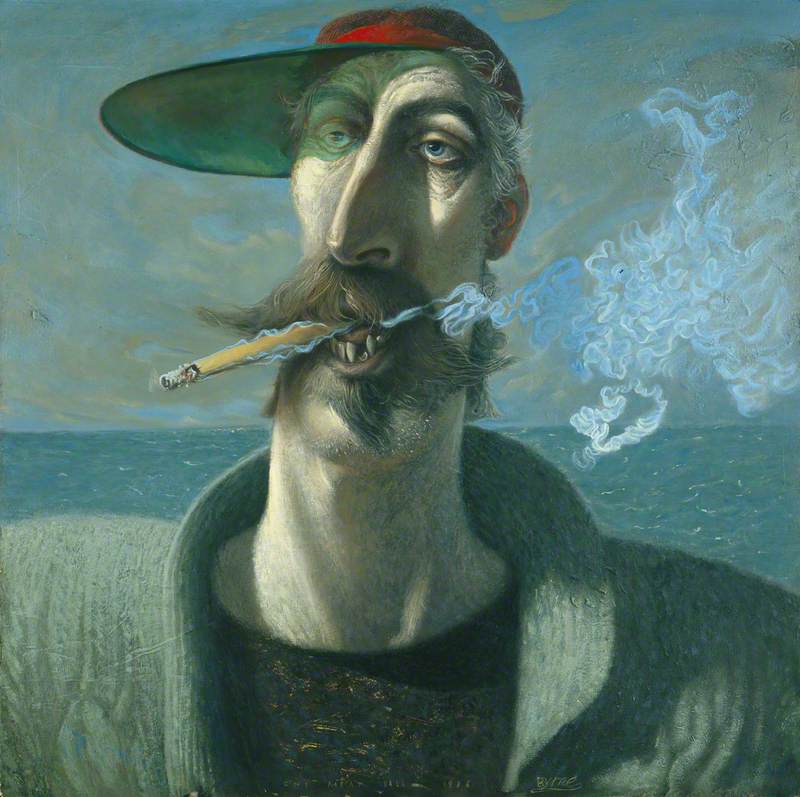

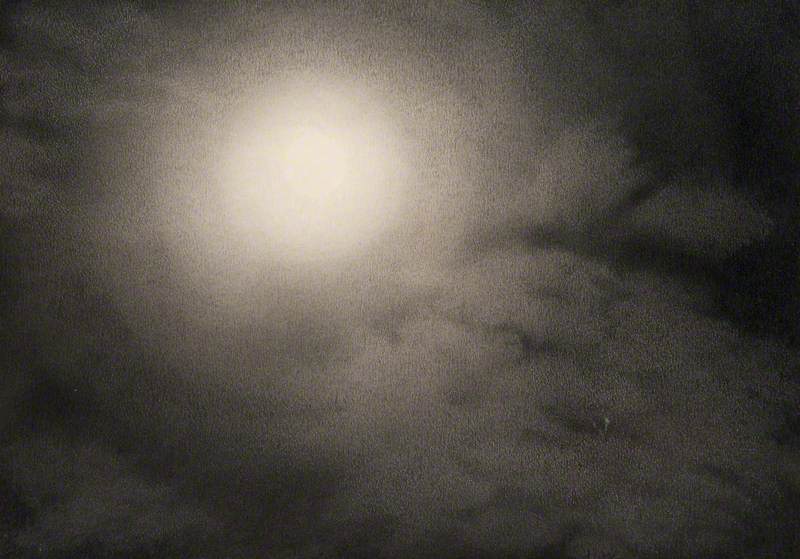

By Self Portrait in 1986, he is on the coast with an expression that is all at sea, his habitual cigarette sending out a cloud of blue smoke. The swirling textures recall a Van Gogh self-portrait and it is hard to tell if he is deliriously happy or off-kilter.

It is a more jovial Byrne we find in 1989's Self Portrait in Stetson, his face elongated, his eyes raised and his moustache jaunty. A choppy sea catches the sunlight behind him and, although the clouds are grey, there is brightness abroad.

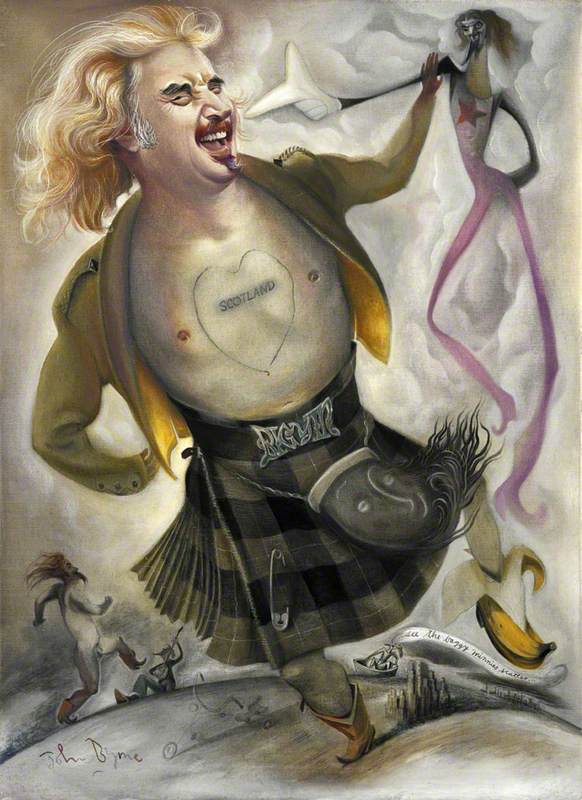

Byrne has said he is the most complex person he knows, finding himself to be a bottomless well of inspiration, not in a narcissistic way, but as a tireless self-analyst. But it is not all about him. The human figure has been Byrne's major preoccupation, never having been especially interested in landscapes and having no inclination towards abstracts. His aim is to capture the spirit of his subjects, something he has done to captivating effect, whether with loved ones, well-known friends or more formal portraits.

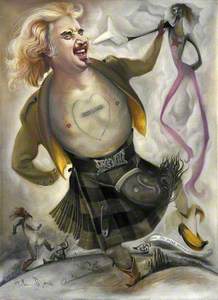

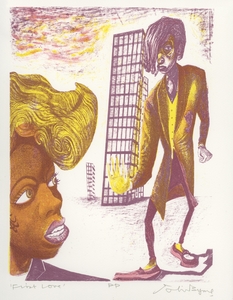

There are few more spirited images than his 2002 vision of his old friend Billy Connolly, his kilt swinging, his sporran smiling and his chest engraved with a Scotland love heart, as if etched in stone. The comedian is giving a characteristic laugh, still wearing one big banana boot, even as he pats aside an image of his thin-limbed younger self.

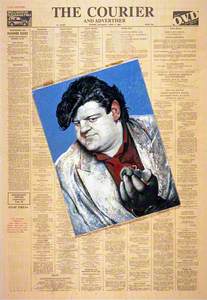

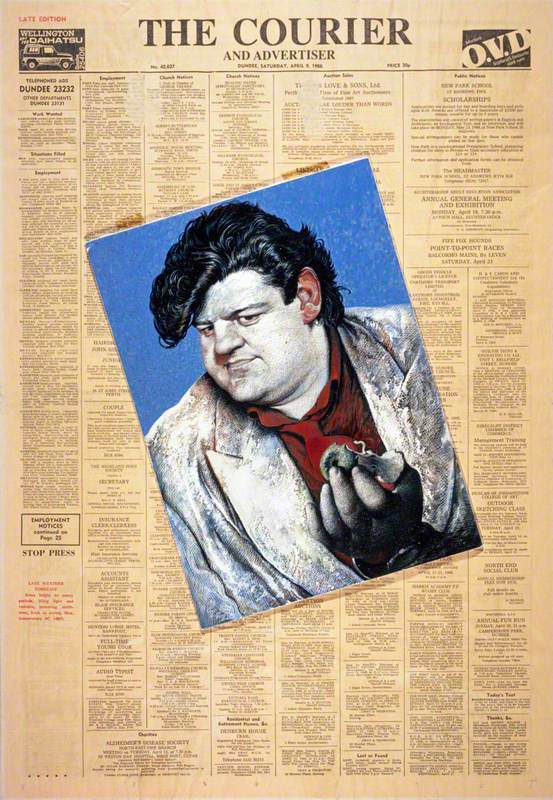

Robbie Coltrane (1950–2022), Actor, as Danny McGlone

1988

John Byrne (1940–2023)

His portrait of Robbie Coltrane, who sealed his reputation in Byrne's 1987 TV series Tutti Frutti, presents the actor with shining quiff and outsize jacket, his eye cautious, his mouth not quite a smile. After Byrne had finished, the painting accidentally fell onto a copy of Dundee newspaper The Courier, where it stuck. The yellowing paper became part of the mounting, adding an extra contrast to the sky blue background.

Byrne has painted with greatest tenderness those dearest to him, be it his former partner Tilda Swinton, his wife Jeanine Byrne, his children to his first wife Alice or the twins he brought up with Swinton. His Portrait of John and Celie shows his two older children as pensive figures, close yet looking away from each other, lost in their thoughts. Like all his family portraits, it has a quiet intimacy.

In 2011, he turned the bedroom stories he told his youngest children, Xavier and Honor, into a large-format picture book, Donald & Benoît. It is about a boy and his black kitten trying to scrape a living in the absence of a father who is presumed lost at sea. The illustrations, with their muted colours and rich, pencil-lined detail, have the same retro quality as much of his writing.

Gather the family around this weekend and listen to the whimsical tale of Donald and Benoit by John Byrne, adapted for the theatre by his wife and award-winning theatre-maker, Jeanine Byrne.

— The Fine Art Society (@TheFineArtSoc) December 15, 2021

From 17-19 December, on #soundstage @PITLOCHRYft.

Book at: https://t.co/cFv2sPCGOY pic.twitter.com/8kvBlKyPby

That an artist who has worked in theatre, television, publishing and the music industry should also be the author of a children's picture book is further confirmation of John Byrne's status as a latter-day Renaissance man.

Mark Fisher, freelance writer and critic

This content was supported by Creative Scotland