Sense of place is a complex phenomenon. Psychologists may be able to tell us more about it than geographers. What did British painter Ivon Hitchens sense in his places? The birds, the sound of the wind, a hundred things he did not paint directly but which informed the rhythms of a picture. How did he inhabit his country?

It seems, for instance, that he had little urge to reconnoitre territory; he didn't walk urgently in all directions, investigating every possible path. He preferred to return over and over to a few favoured haunts. Place works unpredictably on people, and people who love places can respond in the most unpredictable ways of all. Hitchens' chosen spots tended to be hidden, but what he made in them, and made of them, were paintings of utmost exuberance.

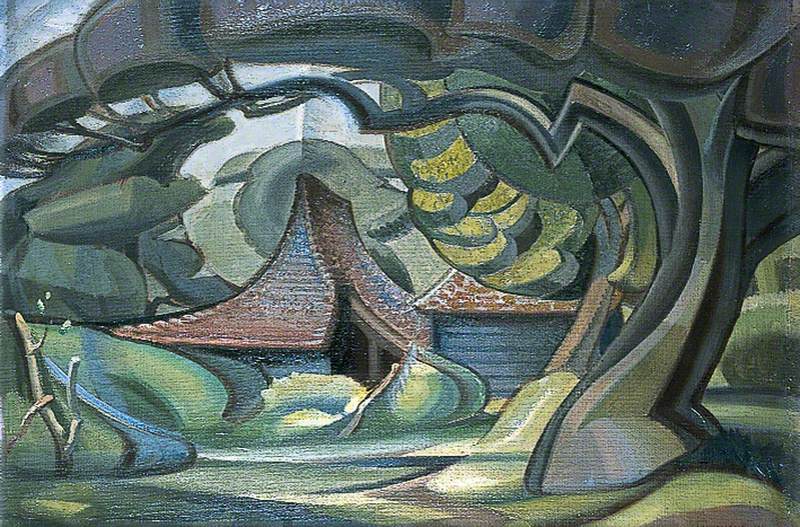

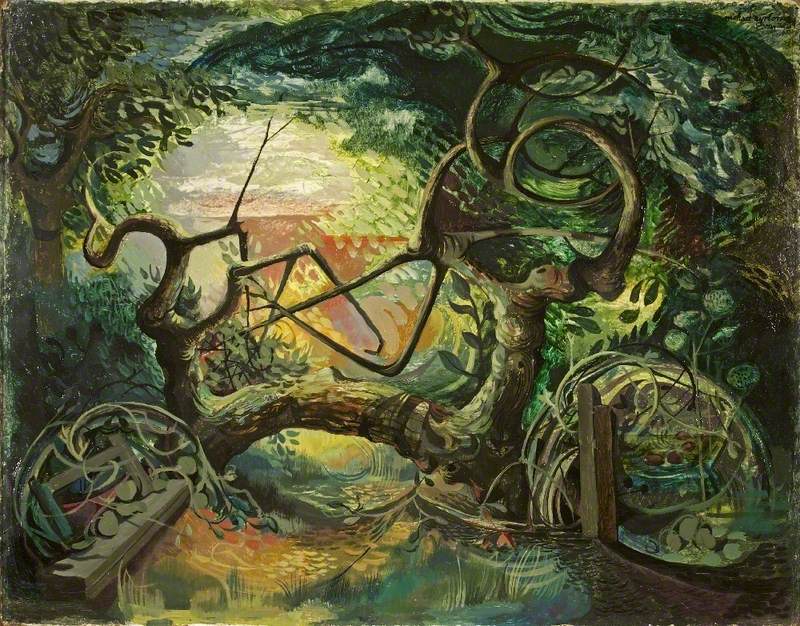

It's clear that Hitchens appreciated the country around him – in particular that surrounding his home and studio at Lavington Common, Sussex – in all its variety. Every so often he painted downland views. But it was the woods and streams that posed the questions he most wanted to answer, or suggested the visual music he most wanted to compose. He looked in one direction through the trees, and then another. He looked ahead of him while remaining aware of what was behind. He drew together the mixed experiences of a whole 'winter walk'. He 'listened' to the conversation between an open passage of mown path and an enclosed screen of undergrowth, and these conversations established the relationships between different parts of a painting. Very rarely did he settle for one point of focus at which all lines of perspective meet. The challenge was in the orchestration of two, three, four or even five 'views' all held together in sequence, each forming part of the whole.

He worked freely with the techniques he had first developed in the Winter Stage paintings at Moatlands in Ashdown Forest (north of the Downs, in the heavily wooded Weald). It was as if he was looking through multiple window panes, each framing a different part of the same surroundings.

Paul Nash often felt himself to be solving the 'equation' set by a landscape. Hitchens, too, was an artist of precise geometries, though with very different intentions. There was for him no symbolic code that made the path through landscape a passage into psychological dream worlds. His paintings do not ask to be explicated. Nature's shapes, lights and compositions, and the movement of colour on canvas, were for him the thing itself.

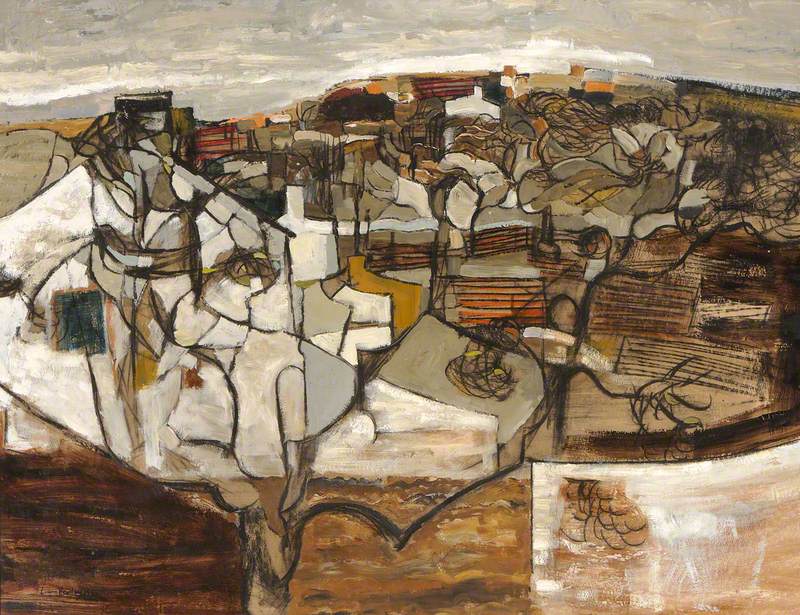

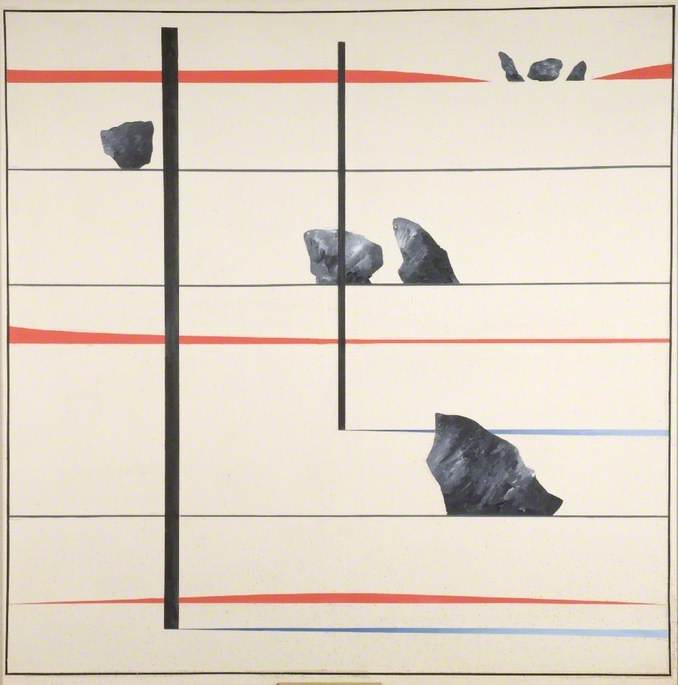

'In England today', wrote Patrick Heron in the mid-1950s, 'Hitchens in West Sussex provides the most distinguished example of [...] profound personal identification of a painter with a special place, or landscape – although, in Cornwall, Peter Lanyon, much younger, has this same reverence for a particular landscape.' The comparison with Lanyon is a fertile one, not least because both artists moved close to abstraction even while immersing themselves more and more deeply in their environments. Their passion for place pushed them far out beyond topographical figuration.

But what's striking, too, is the great contrast in the places they chose. Lanyon stood on exposed granite, submitting himself to the elements, wanting to paint the path of the wind over the sea. Learning to fly gliders, he reinvented landscape painting while airborne. Hitchens, meanwhile, turned landscape painting inside out, by tunnelling into woods and submerging himself in the marginal growth of ponds.

Alexandra Harris, writer and critic

This article is an abridged version of Alexandra Harris's essay 'Hitchens' Places', published in the illustrated catalogue accompanying the exhibition 'Ivon Hitchens: Space through Colour', on at Pallant House Gallery from 29th June to 13th October 2019. The exhibition is the largest on British painter Ivon Hitchens in over 30 years, and covers the whole six decades of his extraordinary career.

Alexandra Harris would like to record her gratitude to the Leverhulme Trust for funding research on Ivon Hitchens as part of a larger project on landscape.